Albert Mueller stands as a poignant figure within the vibrant and often tumultuous landscape of early 20th-century European art. A Swiss artist by birth, Mueller became deeply entwined with the German Expressionist movement, a revolutionary artistic current that sought to convey subjective emotional experience over objective reality. Though his career was tragically cut short by his early death, Mueller's contributions to painting, sculpture, woodcuts, and glass art mark him as a noteworthy, if sometimes overlooked, participant in this radical reshaping of artistic expression. His close association with Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, a titan of German Expressionism, further underscores his immersion in the movement's core.

The Cauldron of Modernity: The Birth of Expressionism

To understand Albert Mueller's artistic journey, one must first appreciate the fertile, yet volatile, ground from which German Expressionism sprang. The late 19th and early 20th centuries were a period of immense societal, industrial, and intellectual upheaval across Europe. Rapid urbanization, burgeoning industrialization, and a growing sense of alienation in an increasingly impersonal world fostered an environment ripe for artistic rebellion. Artists began to reject the staid academic traditions that had long dominated European art, as well as the fleeting impressions of light and color championed by the Impressionists. They sought something more profound, more primal, and more emotionally resonant.

In Germany, this quest for a new artistic language coalesced into Expressionism. It wasn't a monolithic movement with a single manifesto, but rather a collection of artists and groups sharing a common desire to express inner feelings, anxieties, and spiritual yearnings. Key influences included Post-Impressionist painters like Vincent van Gogh, Paul Gauguin, and Edvard Munch, whose use of intense color, distorted forms, and emotionally charged subject matter resonated deeply with the younger generation. The raw power of so-called "primitive" art from Africa and Oceania also provided a vital source of inspiration, offering an alternative to the perceived over-refinement of Western traditions.

Two major groups came to define German Expressionism: Die Brücke (The Bridge), founded in Dresden in 1905, and Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider), established in Munich in 1911. Die Brücke, with artists like Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, Erich Heckel, and Emil Nolde (for a time), aimed to forge a "bridge" to a more authentic and vital future, often depicting urban life, nudes in nature, and portraits with a raw, almost aggressive energy. Der Blaue Reiter, including Wassily Kandinsky, Franz Marc, August Macke, and Gabriele Münter, leaned towards more spiritual and abstract concerns, exploring the symbolic power of color and form. Albert Mueller's work, particularly through his connection with Kirchner, aligns more closely with the ethos of Die Brücke.

Albert Mueller: Life and Artistic Inclinations

Born in 1897, Albert Mueller entered the art world during this period of intense ferment. While detailed information about his early life and formal artistic training remains somewhat scarce in widely accessible records, his Swiss origins are noted. His active period, primarily in the 1920s, placed him directly within the later phase of German Expressionism, a time when the initial shockwaves of the movement had settled, but its stylistic innovations continued to evolve. His relatively short lifespan, ending in 1926, meant his oeuvre was developed over a condensed period, yet it reflects a clear engagement with Expressionist tenets.

Mueller was a versatile artist, comfortable across various media. This multidisciplinary approach was not uncommon among Expressionists, who often sought to break down traditional hierarchies between "fine" art and craft. His involvement in painting, sculpture, woodcuts, and even glass art demonstrates a comprehensive exploration of expressive possibilities. The woodcut, in particular, was a favored medium for Die Brücke artists due to its capacity for stark contrasts, bold lines, and a direct, unmediated quality that suited their desire for raw emotional impact.

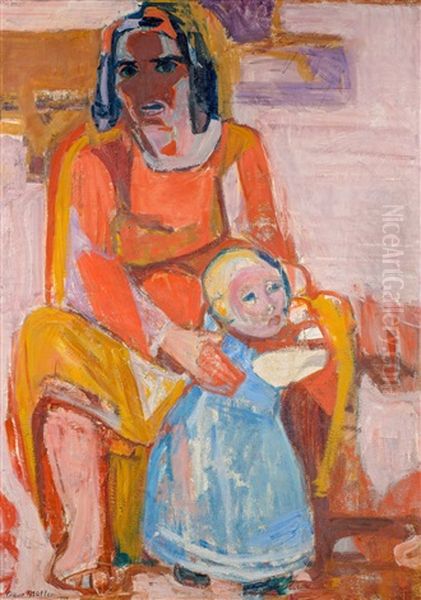

The defining characteristic of Mueller's style, as noted, was his use of strong, often non-naturalistic colors and the deliberate distortion of figures and landscapes. This was not a failing of technical skill, but a conscious choice to prioritize emotional truth over visual accuracy. By exaggerating forms and intensifying hues, Mueller, like his contemporaries, aimed to evoke a particular mood, critique societal norms, or explore the psychological state of his subjects. This approach sought to make the viewer feel the scene, rather than merely observe it.

Key Works and Thematic Concerns

Several works provide insight into Albert Mueller's artistic vision. His woodcut, Mutter mit Kind (Mother with Child) from 1924, tackles a timeless theme. In the hands of an Expressionist, this subject would likely transcend sentimental depiction, perhaps imbuing the figures with a primal strength, a sense of vulnerability, or an intense emotional bond conveyed through simplified, powerful forms and the inherent graphic quality of the woodcut medium. The choice of woodcut itself suggests an affinity with the directness and expressive potential that artists like Kirchner and Heckel had so masterfully exploited.

The oil painting Self-portrait from 1926, the year of his death, would undoubtedly be a significant piece. Self-portraits were a crucial genre for Expressionists, offering a vehicle for intense introspection and the projection of inner turmoil or artistic identity. One can imagine Mueller employing distorted features, a heightened color palette, and vigorous brushwork to convey his psychological state or his perception of himself as an artist in a rapidly changing world. Artists like Egon Schiele and Oskar Kokoschka, Austrian Expressionists, also produced searing self-portraits that laid bare their psyches.

Rebbere in Tessin (1925) points to an engagement with landscape, specifically the Ticino region of Switzerland, known for its dramatic scenery. Expressionist landscapes often transformed nature into a mirror of human emotion. Rather than a picturesque rendering, Mueller's Tessin was likely a vibrant, dynamic interpretation, perhaps with mountains, trees, and water rendered in bold, expressive colors and forms, echoing the work of artists like Franz Marc who sought spiritual resonance in nature, or Kirchner who depicted the Swiss Alps with a similar intensity.

Perhaps one of his most cited works is the oil on canvas Woman in a River Landscape, created around 1925. Measuring 80cm x 98.7cm, this painting likely exemplifies his mature Expressionist style. The theme of the figure in nature, particularly the female nude, was a recurring motif for Die Brücke artists. It symbolized a return to a more primal, uninhibited state, a rejection of bourgeois constraints. Mueller's interpretation might feature a figure integrated into or contrasted with a vividly colored, dynamically rendered landscape, the forms of both woman and environment perhaps simplified or distorted to heighten the emotional impact. The river itself could serve as a potent symbol of life, flux, or the subconscious.

The Indelible Link: Mueller and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner

The relationship between Albert Mueller and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner is a cornerstone of Mueller's biography. Kirchner, a founding member of Die Brücke, was one of the most influential and iconic figures of German Expressionism. His intense, often jarring depictions of Berlin street life, his angular nudes, and his later, more monumental Swiss landscapes defined a significant strand of the movement.

A close friendship with an artist of Kirchner's stature would have been profoundly impactful for Mueller. It suggests shared artistic ideals, mutual respect, and likely, a degree of mentorship or collaborative exchange. Kirchner himself moved to Davos, Switzerland, in 1917, initially for health reasons, and remained there until his death. This Swiss connection might have facilitated or strengthened his bond with the Swiss-born Mueller.

The fact that Kirchner created works depicting Mueller and his family is a testament to the depth of their connection. Portraits within artistic circles often signify admiration and camaraderie. These works by Kirchner would not only be valuable documents of Mueller's likeness but also interpretations filtered through Kirchner's distinctive Expressionist lens, likely characterized by elongated forms, psychological intensity, and vibrant, sometimes clashing colors. Studying these portraits could offer further clues into Mueller's personality and his place within Kirchner's world. This interaction places Mueller firmly within the inner circle of one of Expressionism's leading lights.

Navigating the Artistic Landscape: Contemporaries and Influences

Beyond Kirchner, Albert Mueller operated within a rich artistic ecosystem. The broader German Expressionist movement included a diverse array of talents. While Die Brücke focused on raw, figurative expression, Der Blaue Reiter explored more lyrical and spiritual avenues. Artists like Wassily Kandinsky were pioneers of abstraction, believing in the autonomous expressive power of color and form, akin to music. Franz Marc sought to convey the spiritual essence of animals through vibrant color, while August Macke captured the fleeting joys of modern life with a softer, more poetic palette. Paul Klee, another Swiss artist associated with Der Blaue Reiter, developed a highly personal visual language, rich in wit and symbolism.

While Mueller's style seems more aligned with Die Brücke, the pervasive spirit of experimentation meant that artists were aware of, and often influenced by, developments across different groups. The legacy of earlier artists like Edvard Munch, whose painting The Scream became an icon of modern angst, loomed large. The Fauvist movement in France, with artists like Henri Matisse and André Derain, also shared Expressionism's emphasis on strong color and painterly freedom, and there were certainly cross-currents of influence.

Other notable German Expressionists whose work formed part of this milieu include Otto Mueller (no direct relation, known for his lyrical depictions of nudes, often Roma figures, in harmonious landscapes), Max Pechstein (another Die Brücke member who explored exotic themes), and Conrad Felixmüller, who focused on socially critical subjects. The printmaking revival, central to Expressionism, also saw artists like Käthe Kollwitz produce powerful, emotionally charged works addressing social injustice and human suffering, though her style was perhaps more rooted in realism, it shared the Expressionist intensity.

Versatility in Medium: Beyond the Canvas

Albert Mueller's practice extended beyond painting into sculpture, glass art, and, significantly, graphic arts, particularly woodcuts. The Expressionist embrace of the woodcut was a deliberate revival of an older technique, valued for its directness and its capacity for strong, stark contrasts. The act of carving into wood, the resistance of the material, and the resulting bold, often rough-hewn lines, perfectly suited the Expressionist desire for unmediated, forceful expression. Artists like Kirchner, Heckel, and Schmidt-Rottluff produced a vast body of woodcuts that are considered highlights of the movement. Mueller's Mutter mit Kind in this medium places him squarely within this tradition.

His work in sculpture would have allowed him to explore form in three dimensions, perhaps translating the angularities and emotional distortions of his paintings into tangible objects. Expressionist sculpture, exemplified by artists like Wilhelm Lehmbruck, often featured elongated, attenuated figures conveying a sense of melancholy or spiritual yearning. While specific details of Mueller's sculptural output are less prominent in general surveys, his engagement with the medium speaks to his comprehensive artistic exploration.

Glass art, too, offered unique expressive possibilities, particularly through the use of colored glass and light. This medium, with its historical associations with religious art (stained glass windows), could be re-purposed by Expressionists to create luminous, emotionally charged compositions. Artists like Johan Thorn Prikker were notable in this field. Mueller's involvement suggests an artist keen to explore the full spectrum of visual expression available to him.

A Legacy Cut Short

Albert Mueller's death in 1926 at the young age of 29 or 30 (depending on the precise birth month) is a poignant "what if" in art history. He was active during a crucial period of artistic innovation, and his association with Kirchner placed him at the heart of German Expressionism. His multifaceted output in painting, printmaking, and sculpture demonstrated a significant talent and a deep engagement with the movement's core principles: emotional intensity, subjective vision, and a bold use of color and form.

The brevity of his career means his body of work is smaller than that of contemporaries who lived longer, and perhaps this has contributed to him being less widely known than figures like Kirchner, Nolde, or Marc. However, his contributions are recognized by specialists, and his works appear in collections and exhibitions focusing on German Expressionism. Each piece, from the Woman in a River Landscape to his self-portraits and woodcuts, adds a distinct voice to the complex chorus of Expressionist art.

The impact of German Expressionism itself was profound and far-reaching. Although suppressed by the Nazi regime in the 1930s as "degenerate art" (Entartete Kunst), its influence permeated subsequent artistic developments, including Abstract Expressionism in the United States. The Expressionists' emphasis on subjective experience, their bold formal innovations, and their willingness to confront uncomfortable truths paved the way for many later avant-garde movements. Artists like George Grosz and Otto Dix, associated with the Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) that followed Expressionism, retained some of its critical edge while adopting a more veristic style.

Conclusion: Albert Mueller's Enduring Resonance

Albert Mueller, though his flame burned briefly, was a genuine participant in one of the 20th century's most vital artistic revolutions. His Swiss roots and his active engagement with the German Expressionist scene, particularly his close ties with Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, situate him as an artist who absorbed and contributed to the movement's dynamic energy. His works, characterized by vibrant color, expressive distortion, and a multi-media approach, speak to a passionate artistic temperament.

While he may not have achieved the household-name status of some of his contemporaries, Albert Mueller's art provides valuable insights into the concerns and stylistic explorations of his time. His paintings, woodcuts, and sculptures are a testament to an artist deeply committed to the Expressionist ideal of art as a conduit for profound human emotion and subjective experience. His legacy endures in the artworks he left behind, offering a compelling glimpse into a fervent period of artistic creation and reminding us of the potent, if tragically curtailed, talent that contributed to the rich tapestry of German Expressionism. His story underscores the interconnectedness of the art world, where friendships, collaborations, and shared ideals can shape an artist's journey and their lasting impact.