Ernst Ludwig Kirchner stands as a towering figure in the landscape of 20th-century art, a principal founder and driving force behind German Expressionism. His life and work are inextricably linked, reflecting a tumultuous era of rapid industrialization, urban alienation, world war, and political upheaval. Through canvases vibrant with jarring colors, dynamic, often jagged lines, and emotionally charged subjects, Kirchner sought not just to represent the external world, but to excavate the intense psychological and emotional realities lurking beneath the surface of modern life. His journey took him from architectural studies to the forefront of the avant-garde, through the vibrant but tense streets of Dresden and Berlin, the trauma of war, the serene yet isolating Swiss Alps, and ultimately, to a tragic end under the shadow of Nazi persecution.

Early Life and the Genesis of Die Brücke

Born on May 6, 1880, in Aschaffenburg, Bavaria, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner came from an educated background. His father was a professor of paper sciences at the Technical University in Chemnitz, and his mother descended from a Huguenot family, suggesting a lineage familiar with displacement and resilience. Initially, Kirchner pursued architecture, enrolling at the Königliche Technische Hochschule (Royal Technical University) in Dresden in 1901. However, his true passion lay in the visual arts, a calling that soon eclipsed his architectural ambitions.

Dresden proved to be a fertile ground for Kirchner's artistic development. It was here, amidst his studies, that he encountered three fellow students who shared his burgeoning dissatisfaction with the conservative constraints of academic art: Fritz Bleyl, Erich Heckel, and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff. They were united by a desire to forge a new, authentic German art, one that broke free from the perceived superficiality of Impressionism and the rigid traditions of the academy. They sought an art that was direct, emotionally honest, and deeply rooted in lived experience.

This shared vision culminated in the formation of "Die Brücke" (The Bridge) on June 7, 1905. The name itself, likely suggested by Schmidt-Rottluff, symbolized their intention to bridge the gap between the artistic traditions of the past and the art of the future. They saw themselves as a link to a more vital, expressive form of creativity. Kirchner quickly emerged as a leading figure within the group, not only through the power of his artistic output but also through his efforts in shaping the group's identity and public profile. Die Brücke artists aimed to create art that reflected the intensity and anxieties of modern existence, drawing inspiration from sources as diverse as late Gothic German woodcuts, the bold colors of Fauvism, and the perceived directness of African and Oceanic art.

The early years of Die Brücke in Dresden were marked by intense collaboration and experimentation. The artists often worked closely together, sharing studio spaces and models, developing a collective style characterized by simplified forms, heightened, non-naturalistic color, and a raw, often angular energy. They were influenced by artists like Vincent van Gogh and Edvard Munch, whose works demonstrated the power of art to convey profound emotional states. The French Fauvist movement, particularly the work of Henri Matisse with its liberation of color, also provided significant inspiration during this formative period. Emil Nolde, another pivotal figure in German Expressionism, briefly joined Die Brücke in 1906, further enriching the group's dynamic.

The Dresden and Berlin Years: Capturing Urban Intensity

The period spent in Dresden (until 1911) and subsequently in Berlin (from 1911 until his departure for Switzerland) represents the core of Kirchner's engagement with the modern city. His work from this time pulsates with the energy, dynamism, and underlying tension of urban life. Initially, the Dresden works often focused on studio scenes, landscapes, and nudes depicted in natural settings, such as the famous Moritzburg Lakes paintings, where the artists sought a bohemian escape from city constraints. Works like Marzella (1909-10), a portrait of a young girl rendered with stark lines and intense color, exemplify the Brücke style's raw power.

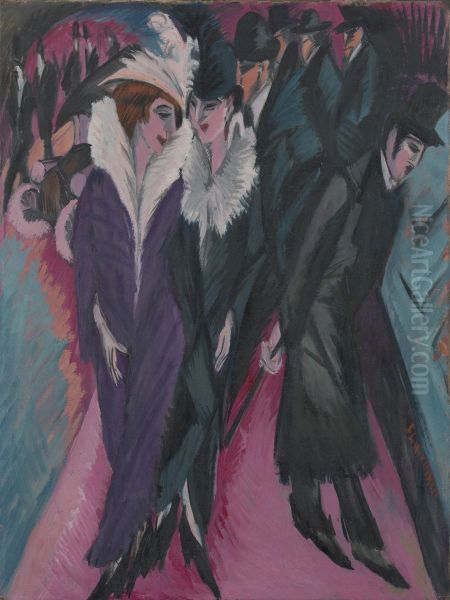

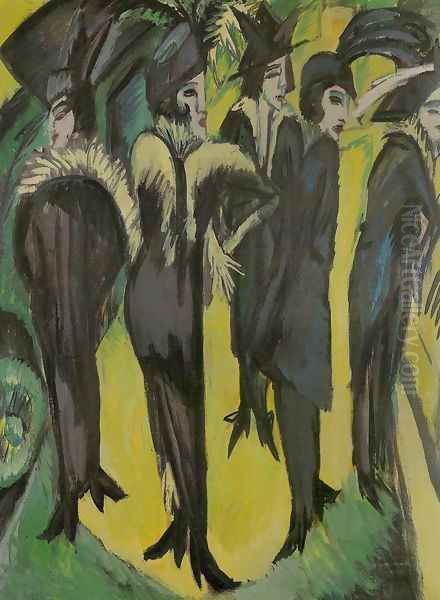

The move to Berlin in 1911 marked a significant shift. Berlin was a larger, faster, more anonymous metropolis, and its atmosphere permeated Kirchner's art. He became fascinated by the city's streets, its cafes, cabarets, and the figures who populated this world – the shoppers, the prostitutes, the dandies, the alienated individuals caught in the urban flow. His celebrated series of Berlin street scenes, painted primarily between 1913 and 1915, are iconic representations of pre-war urban anxiety.

Works like Street, Berlin (1913) depict elongated, angular figures crowded together, yet isolated. The colors are often dissonant, the perspectives tilted and jarring, conveying a sense of unease, artificiality, and nervous energy. These paintings capture the dynamism and allure of the modern city but also its perceived decadence, superficiality, and the psychological fragmentation it induced. Kirchner's sharp, splintered forms, perhaps influenced by Cubism but serving expressive rather than analytical ends, perfectly captured the hectic rhythm and underlying anxieties of Berlin life on the eve of World War I. He was also profoundly influenced by the formal innovations of artists like Paul Cézanne and Paul Gauguin during this period, integrating their structural concerns into his expressive framework.

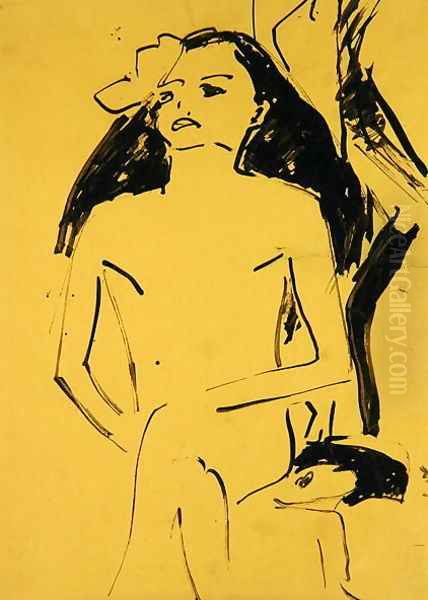

Beyond painting, Kirchner was a prolific printmaker, particularly skilled in woodcut. This medium, with its potential for stark contrasts and raw, expressive lines, aligned perfectly with the Brücke aesthetic. Works like the woodcut Bathing Couple (1910) demonstrate his mastery of the form, reducing figures and setting to their essential, emotionally charged elements. He also explored sculpture, often carving figures directly from wood, echoing the forms found in the African and Oceanic art that fascinated him and his colleagues, seeking a similar primal energy and directness.

War, Trauma, and a Shift in Perspective

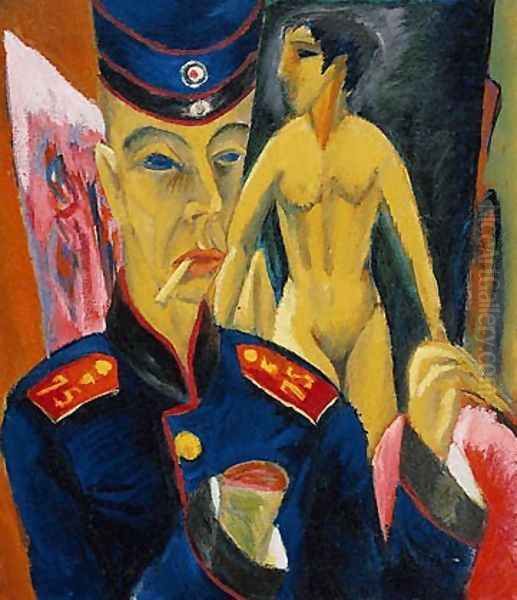

The outbreak of World War I in 1914 shattered the vibrant, if tense, world Kirchner had been depicting. Like many artists of his generation, he initially volunteered for service, joining the field artillery. However, the brutal realities of military life and the looming threat of the front proved devastating for his sensitive temperament. He suffered a severe mental and physical breakdown before ever seeing active combat, experiencing profound anxiety, paralysis, and an addiction to medication prescribed for his condition.

This traumatic period is starkly reflected in works like his harrowing Self-Portrait as a Soldier (1915). Here, Kirchner depicts himself in uniform, gaunt and haunted, with an amputated painting hand – a symbolic representation of his creative and psychological castration by the war. The background features a nude figure, perhaps representing his art or his former life, now inaccessible. The painting is a powerful testament to the devastating impact of the war on the individual psyche, a theme echoed in the work of contemporaries like Oskar Kokoschka and Egon Schiele, who also grappled with the war's horrors.

Declared unfit for service, Kirchner spent much of the war years in and out of sanatoriums in Germany (Königstein im Taunus) and Switzerland, battling nervous breakdowns, lung problems, and drug dependency. Despite his fragile state, he continued to create, producing drawings and prints, including illustrations for Adelbert von Chamisso's Peter Schlemihl and a powerful series of woodcuts illustrating the Apocalypse. These works reveal his preoccupation with themes of suffering, mortality, and spiritual crisis, filtered through his distinctively angular and emotionally raw style. His partner, Erna Schilling, whom he had met in Berlin around 1912 and who became a frequent model and lifelong companion, provided crucial support during these difficult years, managing his affairs in Berlin while he convalesced.

The Davos Period: Alpine Majesty and Abstraction

In 1917, seeking refuge and recovery, Kirchner moved permanently to Davos, Switzerland. The dramatic Alpine landscape surrounding his new home offered a stark contrast to the urban environments that had previously dominated his work. Initially settling in a farmhouse on the Stafelalp and later moving to a house called "In den Lärchen" and finally "Wildboden," Kirchner found a measure of peace and a new source of artistic inspiration in the mountains.

His Davos paintings depict the majestic peaks, the changing seasons, the lives of the local farmers, and the dramatic interplay of light and shadow on the snow-covered slopes. While the expressive intensity remained, his style gradually evolved. The jagged nervousness of the Berlin street scenes gave way to calmer, more monumental compositions. His forms became somewhat more simplified and abstract, his colors often cooler, reflecting the clear mountain air and vast landscapes. Works from this period often show a greater emphasis on structure and pattern, perhaps reflecting a search for order amidst his internal turmoil.

He painted the mountains, the peasants working the land, and scenes of rural life, finding a connection to a simpler, seemingly more authentic existence far removed from the complexities and corruption he perceived in the city. Yet, even in these seemingly idyllic scenes, an underlying tension can sometimes be felt, a reflection of his ongoing struggles with his health and his anxieties about the world beyond the Alps. He continued to work across various media, including painting, drawing, printmaking, sculpture, and even tapestry design, collaborating with weavers like Lise Gujer. Despite the relative isolation, he maintained connections with the art world and achieved growing international recognition during the 1920s. His relationship with Erna Schilling continued, though it remained complex; despite their long partnership, they never formally married, partly due to Kirchner's anxieties and perhaps his immersion in his Swiss life.

Artistic Style and Techniques Summarized

Kirchner's artistic style is synonymous with German Expressionism. Its core tenets include the primacy of subjective feeling over objective reality, the use of intense, non-naturalistic color to convey emotion, distorted forms and perspectives to heighten expressive impact, and a fascination with the raw, the primitive, and the psychologically complex.

His early work shows the influence of Post-Impressionism and Fauvism (especially Matisse) in its bold color and brushwork. The encounter with African and Oceanic art, accessible through ethnographic museums in Dresden, led to a simplification of form, angularity, and an interest in masks and totemic figures, seeking a more direct, unmediated form of expression. His Berlin period saw the assimilation of urban dynamism and anxiety, resulting in jagged lines, compressed spaces, and elongated figures that convey the city's nervous energy.

Throughout his career, Kirchner demonstrated versatility across media. His paintings are characterized by their vibrant, often clashing colors and dynamic compositions. His woodcuts are particularly significant, reviving the medium with a modern sensibility. He exploited the grain of the wood and employed bold, rough cuts to achieve stark, powerful images, a technique shared and developed by fellow Brücke artists like Heckel. His drawings, often quick sketches capturing movement and character, possess a remarkable immediacy and fluidity, as seen in works like Dancer (1930). His sculptures, typically carved from wood, share the angularity and expressive force of his two-dimensional work.

Confrontation with Nazism and Tragic End

Despite achieving considerable recognition in the 1920s and early 1930s, including membership in the Prussian Academy of Arts, Kirchner's later years were overshadowed by the rise of Nazism in Germany. The Nazi regime condemned modern art, particularly Expressionism, as "degenerate" ("Entartete Kunst"), viewing it as un-German, Jewish-influenced, or mentally diseased.

In 1933, Kirchner was forced to resign from the Prussian Academy. The situation escalated dramatically in 1937 with the infamous "Degenerate Art" exhibition organized by the Nazis in Munich, designed to ridicule and vilify modern artists. Over 600 of Kirchner's works were confiscated from German public collections. Many were sold abroad, while others were tragically destroyed. This official persecution and the vilification of the art he had dedicated his life to creating profoundly distressed Kirchner, who was already battling chronic health issues and psychological fragility.

The annexation of Austria by Germany in March 1938 intensified his fears that Germany might invade Switzerland. Overwhelmed by despair, deteriorating health, the destruction of his artistic legacy in his homeland, and the looming threat of war, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner took his own life with a gunshot on June 15, 1938, near his home in Frauenkirch-Wildboden, outside Davos. Erna Schilling remained in their house until her death.

Legacy and Influence

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner's legacy is immense. As a co-founder and leading spirit of Die Brücke, he played a crucial role in defining German Expressionism, one of the most significant movements in early 20th-century modernism. His art provided a powerful, often unsettling, reflection of the anxieties and transformations of his time, capturing the intensity of urban life, the trauma of war, and the search for meaning in a rapidly changing world.

His bold use of color, dynamic compositions, and emotionally charged subject matter continue to resonate. He demonstrated the power of art to explore psychological depths and critique social conditions. His pioneering work, particularly the Berlin street scenes and his expressive woodcuts, remains iconic. Although persecuted by the Nazis, his reputation was restored after World War II, and he is now recognized as a master of modern art.

His influence extends to subsequent generations of artists. Post-war German artists like Georg Baselitz and Jörg Immendorff looked back to Kirchner and the Expressionists as they grappled with Germany's recent past and forged their own Neo-Expressionist styles. His work also found appreciation internationally, partly thanks to figures like the photographer and gallerist Alfred Stieglitz, who helped introduce European modernism, including German Expressionism, to American audiences. He stands alongside contemporaries like Max Beckmann, Erich Heckel, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, and Emil Nolde as a defining figure of his artistic generation in Germany.

Major Works and Collections

Kirchner produced a vast body of work throughout his career. Some of his most celebrated pieces include:

Marzella (1909-10)

Bathing Couple (woodcut, 1910)

Street, Berlin (1913)

Five Women on the Street (1913)

Self-Portrait as a Soldier (1915)

The Red Tower in Halle (1915)

Davos in Snow (c. 1923)

Dancer (drawing, 1930)

His works are held in major museums worldwide. The most significant collection is housed at the Kirchner Museum Davos, dedicated solely to his life and art, holding paintings, sculptures, prints, drawings, sketchbooks, photographs, and archival materials. Other important collections can be found at the Städel Museum in Frankfurt, the Brücke Museum in Berlin, the Museum Ludwig in Cologne, the Pinakothek der Moderne in Munich, and the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York. The North Carolina Museum of Art played a key role in his posthumous reception in the United States by hosting his first major American retrospective in 1958.

Conclusion

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner's life was one of intense creativity intertwined with profound personal struggle. He channeled the energies, anxieties, and contradictions of the early 20th century into an art of startling emotional power and visual innovation. From the revolutionary fervor of Die Brücke to the nervous intensity of his Berlin scenes, the trauma of war, and the majestic landscapes of his Swiss exile, his work provides a compelling visual diary of both an individual psyche and a turbulent historical period. Persecuted in his lifetime, Kirchner's art ultimately triumphed, securing his place as a foundational figure of Expressionism and a master whose work continues to captivate and provoke audiences today. His bridge to the future of art remains strong and vital.