An Introduction to the Artist

Johann Joseph Eugen von Guerard, often known simply as Eugen von Guerard, stands as a pivotal figure in the annals of 19th-century landscape painting, particularly renowned for his meticulous and evocative depictions of the Australian wilderness. Born in Vienna, Austria, in 1811, his life and art bridged the Old World traditions of European Romanticism with the raw, untamed beauty of a newly colonized continent. His work is characterized by a profound reverence for nature, a scientific precision in observation, and a capacity to imbue his scenes with a sense of the sublime, reflecting both his rigorous training and his personal encounters with diverse terrains. This exploration delves into the multifaceted career of von Guerard, tracing his artistic lineage, his transformative experiences in Australia, his significant contributions to its burgeoning art scene, and his enduring legacy.

Early Life and Artistic Foundations in Europe

Eugen von Guerard's artistic journey began under the direct influence of his father, Bernhard von Guerard. Bernhard was a court painter, specializing in miniatures, in the service of Francis I, Emperor of Austria. This familial environment undoubtedly provided young Eugen with his initial exposure to artistic practice and the disciplined life of a painter. The early 19th century in Vienna was a period of rich cultural ferment, with the lingering echoes of Classicism giving way to the burgeoning ideals of Romanticism, which emphasized emotion, individualism, and the awe-inspiring power of nature.

Following his father's passing, von Guerard's formal artistic education took him to Italy, the traditional finishing school for aspiring European artists. Between 1830 and 1838, he spent considerable time in Rome and Naples. In Rome, he immersed himself in the study of the Old Masters, particularly the great landscape painters of the 17th century. He is known to have studied the works of artists like Claude Lorrain and Nicolas Poussin, whose classical, idealized landscapes, structured compositions, and masterful handling of light left an indelible mark. He also absorbed the influence of Salvator Rosa, whose wilder, more dramatic and picturesque scenes offered a counterpoint to the Claudian ideal. During this period, he is also noted to have been a student of Giovanni Battista Bassi, an Italian landscape painter who, though perhaps less internationally famed, would have provided practical instruction in the techniques of landscape art.

His pursuit of artistic excellence then led him to Germany, specifically to the Düsseldorf Academy (Staatliche Kunstakademie Düsseldorf) around 1839. The Düsseldorf School was, at that time, one of the most influential art academies in Europe, renowned for its emphasis on detailed realism, meticulous technique, and often, grand historical or religious subjects, as well as a strong tradition of landscape painting. Here, von Guerard studied under the tutelage of Johann Wilhelm Schirmer, a leading figure in the Düsseldorf school of landscape painting. Schirmer encouraged his students to paint directly from nature while also imbuing their works with a sense of poetic or historical narrative. This training honed von Guerard's skills in precise observation and detailed rendering, characteristics that would become hallmarks of his style. He also associated with other artists of the German Romantic movement, such as Karl Friedrich Lessing, who was known for his historical and landscape paintings, and was part of a composition society that included Lessing. The broader German Romantic landscape tradition, exemplified by artists like Caspar David Friedrich with his spiritual and symbolic interpretations of nature, also formed part of the intellectual and artistic milieu that shaped von Guerard.

The Call of the Antipodes: Journey to Australia

The mid-19th century was an era of global exploration, migration, and the pursuit of fortune. In 1852, lured by the promise of the Victorian gold rush, Eugen von Guerard embarked on a life-changing journey to Australia. Like many others, he initially tried his hand at gold prospecting in the Ballarat region. However, his endeavors in the goldfields proved largely unsuccessful in terms of material wealth. This period, though financially unrewarding, was artistically invaluable. He meticulously documented his experiences and the landscapes of the goldfields in detailed sketchbooks, capturing not only the terrain but also the life, dangers, and social fabric of these frontier communities.

His sketches from this time reveal an artist keenly observing the unique flora, fauna, and geological formations of the Australian continent, so different from the European landscapes he knew. He recorded the daily activities of miners, the makeshift settlements, and the often-harsh conditions. These visual diaries formed a rich repository of source material for his later, more finished oil paintings. The Australian environment, with its ancient landforms, distinctive eucalyptus forests, and dramatic atmospheric effects, offered a new and exciting challenge to his European-trained sensibilities.

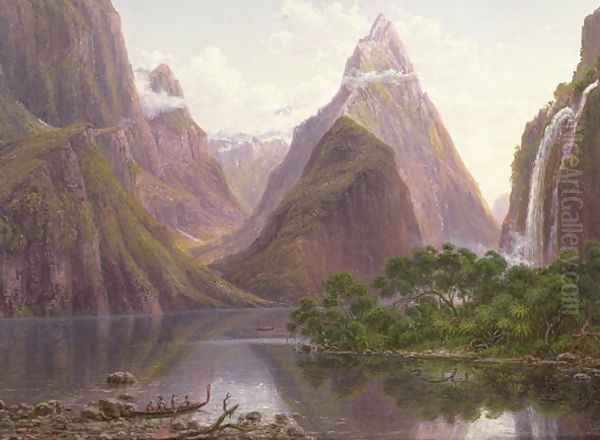

Recognizing that his true calling lay in art rather than mining, von Guerard soon transitioned back to his profession as a painter. He began to travel extensively throughout Victoria, New South Wales, and Tasmania, and later even New Zealand, seeking out picturesque and sublime scenery. His European training, particularly the Düsseldorf emphasis on topographical accuracy combined with Romantic sensibility, equipped him perfectly to capture the grandeur of these new landscapes for a colonial audience eager to see their adopted land represented.

A Romantic Vision of the Australian Landscape

Eugen von Guerard quickly established himself as one of colonial Australia's foremost landscape painters. His style was a unique fusion of the detailed, almost scientific observation encouraged by the Düsseldorf School and the Romantic quest for the sublime – that sense of awe, wonder, and sometimes terror, inspired by the grandeur of nature. He painted for a clientele of wealthy pastoralists, merchants, and public institutions, who commissioned views of their estates, depictions of notable natural landmarks, and panoramic vistas.

His paintings are characterized by their meticulous detail, where every leaf, rock, and tree is rendered with painstaking care. This precision was not merely for show; it reflected a genuine scientific interest in botany and geology, aligning with the 19th-century enthusiasm for empirical observation and classification. Yet, his works were more than mere topographical records. He skillfully employed compositional devices, atmospheric effects, and a subtle manipulation of light and shadow to evoke mood and convey the immense scale and ancient quality of the Australian wilderness. He often included small human figures in his landscapes, not as central subjects, but to emphasize the vastness of nature and humanity's place within it, a common trope in Romantic landscape painting.

Among his most celebrated works is Tower Hill (1855), an extinct volcanic crater in western Victoria. Commissioned by the pastoralist James Dawson, this painting is remarkable for its detailed depiction of the pre-colonial vegetation, based on careful studies and, reportedly, Dawson's own knowledge of the area's original flora. It has since become an important ecological document, aiding in the revegetation of the site.

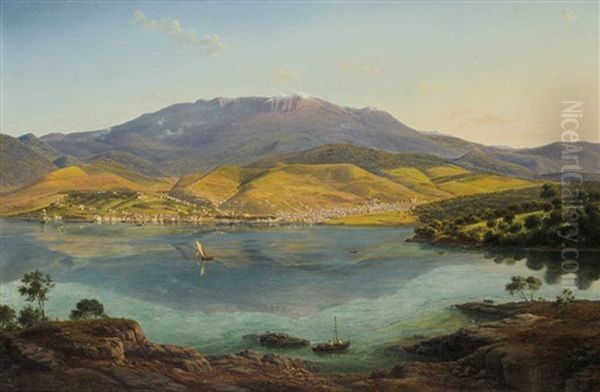

Another iconic work is Ferntree Gully in the Dandenong Ranges (1857). This painting captures the lush, verdant interior of a rainforest gully, with towering tree ferns and a palpable sense of moist, filtered light. It exemplifies his ability to render intricate botanical detail while conveying the immersive, almost spiritual atmosphere of the dense forest. His View of Hobart Town, with Mount Wellington in the Background (1856) showcases his skill in panoramic cityscapes integrated with dramatic natural backdrops, a popular genre of the time.

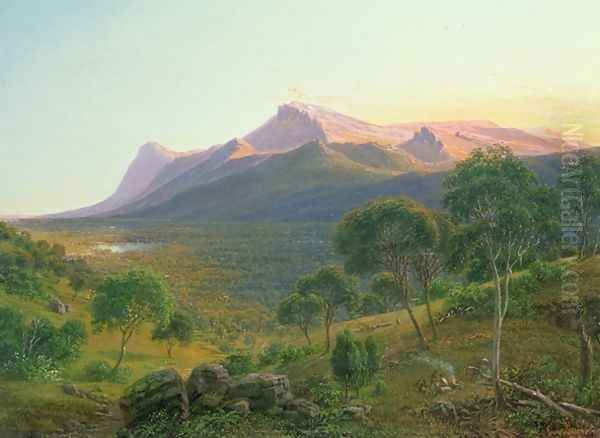

Further demonstrating his ambition and skill in capturing the epic scale of the Australian continent is North-east view from the northern top of Mount Kosciusko (1863). This panoramic masterpiece, one of his largest, presents a breathtaking vista from Australia's highest peak, conveying the ruggedness and expansive emptiness of the alpine region. Similarly, Bushfire between Mount Elephant and Timboon (c. 1857-1859) dramatically captures a uniquely Australian phenomenon, showcasing his ability to depict nature's more destructive yet awe-inspiring forces, a theme that resonated with the Romantic fascination with the sublime. These works, among many others, solidified his reputation and provided a defining visual narrative of the Australian landscape for generations.

Engagement with Indigenous Cultures and Scientific Interests

Von Guerard's time in Australia was not solely focused on depicting the landscape; he also showed a keen interest in the Indigenous peoples of Australia and their cultures, as well as in the natural sciences. This was somewhat unusual for colonial artists of his time, many of whom either ignored or romanticized Aboriginal subjects in stereotypical ways.

His journals and sketchbooks contain observations and drawings of Aboriginal people, their camps, and their artifacts. He developed a significant friendship with James Dawson, the pastoralist who commissioned Tower Hill. Dawson was a notable figure in his own right: a pastoralist, but also a conservationist, ethnographer, and an advocate for Aboriginal people, particularly the Djab wurrung and Girai wurrung peoples of Victoria's Western District. Through Dawson, von Guerard likely gained deeper insights into local Indigenous cultures.

There is evidence of his interaction with Indigenous artists, most notably Johnny Kangatong (also known as Johnny Dawson or Prophet), a Gunditjmara artist from the Western District. Their interactions suggest a level of mutual respect and artistic exchange. Von Guerard's interest extended to collecting Aboriginal artifacts, alongside other natural history specimens like coins, shells, and fossils. This collecting habit reflected the broader 19th-century passion for cataloging and understanding the natural and cultural world. A significant portion of his collection of Aboriginal cultural items was later donated to the Berlin Museum, providing valuable ethnographic material.

His scientific curiosity is evident in the precision of his botanical and geological renderings. He corresponded with scientists such as the German-born geologist and meteorologist Georg von Neumayer, who was a prominent scientific figure in Melbourne at the time. This connection underscores von Guerard's desire for accuracy and his alignment with the scientific spirit of the age, which saw art and science as complementary ways of understanding the world. His detailed landscapes often served not just as aesthetic objects but also as quasi-scientific documents of Australia's unique environment.

Institutional Role and Legacy in Colonial Australia

Eugen von Guerard's influence extended beyond his own artistic output; he played a significant role in the development of art institutions in colonial Victoria. In 1870, he was appointed the first Master of the School of Painting at the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne, a position he held until 1881. In this capacity, he was responsible for training a new generation of Australian artists. His curriculum, based on the academic traditions of Europe, emphasized drawing from casts, studying the Old Masters, and meticulous technique.

While his teaching methods were traditional, and perhaps sometimes seen as rigid by students eager for more modern approaches, he laid a foundational structure for art education in the colony. Among the artists who would have been aware of or indirectly influenced by his presence and the standards he set were figures who later became prominent in the Australian art scene, though direct student lists are not always extensively documented in easily accessible records. However, artists like Tom Roberts, Frederick McCubbin, and Arthur Streeton, key figures of the later Heidelberg School, would have been emerging during or shortly after von Guerard's tenure, and while their style diverged significantly towards Impressionism, the institutional framework von Guerard helped establish was part of the environment in which they developed.

Concurrently with his teaching role, von Guerard also served as the Curator of the National Gallery of Victoria. In this role, he was involved in acquisitions and the overall direction of the gallery, further shaping the artistic tastes and cultural landscape of Melbourne, which was then one of the wealthiest cities in the world due to the gold rush.

His contemporaries in the Australian art scene included artists like Conrad Martens, who, though arriving earlier, also specialized in Romantic landscapes, primarily in New South Wales. S.T. Gill was renowned for his lively watercolor sketches of goldfield life and colonial society, offering a different, more anecdotal perspective than von Guerard's grander visions. Later, artists like the Swiss-born Nicholas Chevalier, who arrived in the 1850s, and Louis Buvelot, another Swiss artist who arrived in 1865, also made significant contributions to Australian landscape painting. Buvelot, in particular, is often seen as a bridge figure, influencing the plein-air approach of the Heidelberg School. Von Guerard's work, with its Düsseldorf precision, stood somewhat apart from these, yet it set a high standard for technical accomplishment.

Later Years and Enduring Influence

In 1882, after nearly three decades in Australia, Eugen von Guerard and his wife Louise returned to Europe. The decision was prompted by a combination of factors, including the loss of his investments in a bank crash and perhaps a desire to spend his later years closer to his European roots and family. They settled in London, where his daughter Victoria and her husband had moved. He continued to paint, though his output in these later years was less prolific. He passed away in London in 1901, at the age of 89.

Despite his departure from Australia, his legacy on the continent remained significant. His paintings became iconic representations of the 19th-century Australian landscape, valued for both their artistic merit and their historical and environmental documentation. For many years, his style was perhaps seen as somewhat old-fashioned compared to the Impressionist-influenced nationalism of the Heidelberg School. However, in more recent decades, there has been a significant re-evaluation and renewed appreciation of his work.

Art historians now recognize the complexity of his vision, which combined Romantic aesthetics with scientific inquiry and a subtle engagement with the colonial experience. His meticulous detail, once perhaps seen as merely illustrative, is now appreciated for its profound observational power. His depiction of vast, ancient landscapes, often untouched by European settlement or showing its nascent stages, resonates with contemporary concerns about environmentalism and the historical impact of colonization.

Internationally, von Guerard can be seen in the context of other 19th-century landscape painters who documented newly explored or "exotic" territories with a combination of Romantic sensibility and scientific detail. His work bears comparison with artists of the Hudson River School in America, such as Albert Bierstadt or Frederic Edwin Church, who similarly painted grand, detailed canvases of the American West and South America, capturing the sublime beauty of these "New World" landscapes. Like them, von Guerard provided a European audience, and the colonists themselves, with powerful visual interpretations of unfamiliar terrains. His paintings also share affinities with the work of other European artists who traveled, such as Edward Lear, known for his topographical landscapes from his extensive travels.

Conclusion: The Enduring Vision of Eugen von Guerard

Eugen von Guerard's contribution to art history, particularly within Australia, is undeniable. He was more than just a skilled painter of landscapes; he was a visual chronicler of a continent undergoing profound transformation. His Austrian birth and European training provided him with a rich artistic heritage, which he skillfully adapted to the unique challenges and inspirations of the Australian environment. From the classical ideals of Poussin and Claude, through the Romanticism of the Düsseldorf School under Schirmer, to his own encounters with the Australian bush, goldfields, and Indigenous cultures, von Guerard forged a distinctive artistic voice.

His works, such as Tower Hill, Ferntree Gully in the Dandenong Ranges, and North-east view from the northern top of Mount Kosciusko, remain masterpieces of 19th-century landscape art. They offer viewers a window into the past, meticulously detailing the natural world as he observed it, while simultaneously imbuing these scenes with a sense of awe and the sublime that transcends mere topography. His role as an educator and curator at the National Gallery of Victoria further cemented his influence on the development of Australian art.

Today, Eugen von Guerard is celebrated for his technical mastery, his dedication to capturing the truth of nature as he saw it, and his ability to convey the unique character and grandeur of the Australian landscape. His paintings are not only beautiful artistic achievements but also valuable historical and ecological documents, continuing to inspire and inform our understanding of Australia's past and its enduring natural heritage. His journey from the courts of Vienna to the wilderness of Australia is a testament to the transformative power of art and the enduring human fascination with the natural world.