John Sell Cotman stands as one of the most significant figures in the history of British watercolour painting and etching. Born on May 16, 1782, in Norwich, England, and passing away in London on July 24, 1842, Cotman's life spanned a period of great change and development in British art. He was a principal member of the Norwich School of painters, a group celebrated for its depiction of the landscapes and life of rural Norfolk. Though his genius was not always fully recognized during his lifetime, his reputation has grown immensely, securing his place as a master of line, colour, and composition.

Cotman's artistic journey began in his hometown of Norwich, where his father was a prosperous silk and lace merchant. Despite his family's business background, young John Sell displayed a clear aptitude and passion for art. Forsaking a future in the family trade, he made the pivotal decision to move to London in 1798 to pursue a career as an artist. This move placed him at the vibrant heart of the British art world at the turn of the nineteenth century.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in London

Upon arriving in London, Cotman quickly immersed himself in the city's artistic circles. He found employment colouring prints for the publisher Rudolph Ackermann, a common starting point for aspiring artists of the time. Crucially, he gained access to the informal academy run by Dr. Thomas Monro, a physician and art patron whose home was a meeting place for young talents. There, Cotman likely studied and copied works by established masters, honing his skills alongside other promising artists.

His talent soon brought him into contact with some of the leading figures of the burgeoning English watercolour school. He became acquainted with Joseph Mallord William Turner, arguably the most famous British painter of the era, and Thomas Girtin, whose tragically short career profoundly influenced the development of watercolour painting. Cotman joined the sketching society founded by Girtin, a group dedicated to drawing historical and landscape subjects in the evenings. This association was invaluable, providing stimulus, camaraderie, and exposure to innovative techniques.

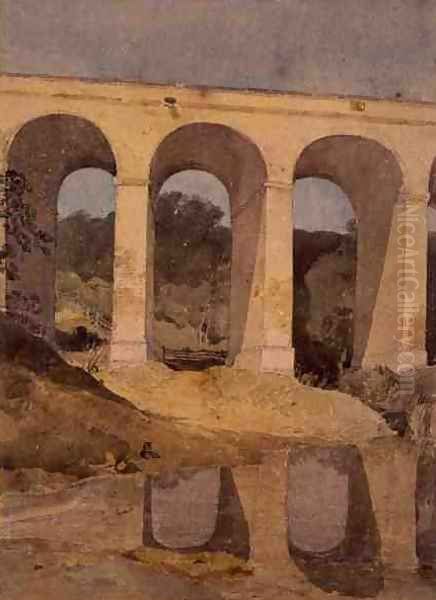

During these formative London years, Cotman also associated with other notable artists such as Peter De Wint, another significant watercolourist known for his broad, atmospheric landscapes. They undertook sketching tours together, travelling to areas like Wales and Surrey between 1800 and 1802. These excursions provided Cotman with rich subject matter. His depictions of Welsh scenery, particularly the mountains and valleys, were exhibited at the Royal Academy between 1800 and 1806, showcasing his developing style and technical proficiency. Works like the powerful watercolour Chirk Aqueduct (c. 1802-1803) date from this period, demonstrating his early mastery of structure and atmospheric effect.

Cotman's early style was significantly influenced by Girtin, particularly in his use of broad washes and a limited, harmonious palette. He quickly developed his own distinctive approach, characterized by a strong sense of pattern, simplification of form, and an almost abstract quality in his arrangement of shapes and colours. He received patronage from figures like Sir George Beaumont, a prominent collector and amateur artist who played a key role in the founding of the National Gallery.

The Norwich Years: Teaching and the Norwich Society

Despite his growing connections and exhibition record in London, Cotman decided to return to his native Norwich in 1806. This move marked a new phase in his career, one deeply rooted in his home region. He set up a practice as a drawing master, opening a school of drawing and design. Teaching became a significant part of his life, providing a necessary, albeit often precarious, income. He developed a "circulating library" system, lending out his own drawings and prints for his pupils to copy, a practical method of instruction.

His return coincided with the flourishing of the Norwich Society of Artists, the first provincial art society founded in Britain (in 1803 by John Crome and Robert Ladbrooke). Cotman joined the society in 1807 and quickly became a leading figure. He exhibited regularly at their annual shows, contributing significantly to the group's reputation. In 1811, he served as the Society's President, a testament to the respect he commanded among his peers, who included artists like James Stark and George Vincent, both pupils of John Crome.

In 1809, Cotman married Ann Miles, the daughter of a local farmer. The couple would have five children who survived infancy, several of whom followed artistic paths. His sons, Miles Edmund Cotman and John Joseph Cotman, both became landscape painters, often working in styles influenced by their father. Miles Edmund, in particular, frequently assisted his father, especially during the later London years. However, family life was also marked by challenges, including financial instability and recurring bouts of depression that afflicted Cotman throughout his life, later diagnosed retrospectively as likely bipolar disorder. These struggles impacted his family, with some of his children also experiencing mental health difficulties.

During his Norwich period, Cotman undertook extensive sketching tours throughout Norfolk and neighbouring counties. He developed a profound interest in the region's architectural heritage – its churches, abbeys, castles, and domestic buildings. This fascination led to one of his most ambitious projects: the publication of series of etchings documenting these structures.

Artistic Style and Techniques

John Sell Cotman's art is distinguished by its unique blend of topographical accuracy, decorative sensibility, and innovative technique, particularly in watercolour and etching.

Watercolour Mastery

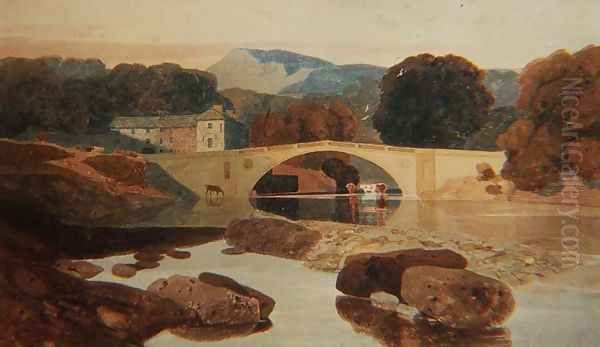

Cotman is revered as one of the great masters of the watercolour medium. His approach evolved throughout his career but consistently displayed a remarkable control over washes and a sophisticated understanding of colour and composition. His early works, especially those produced during his stay near Greta Bridge in Yorkshire around 1805, are considered high points of the medium.

Greta Bridge (c. 1805) exemplifies this phase. It is characterized by broad, flat washes of pure, luminous colour applied with extraordinary precision. Cotman simplified complex forms into interlocking planes, creating compositions that possess an almost abstract beauty. He deliberately avoided strong chiaroscuro (light and shadow contrasts) and fussy detail, focusing instead on the harmonious relationship of shapes and tones. His palette was often cool and restrained, yet capable of conveying subtle atmospheric effects. This style, emphasizing pattern and flat design, was remarkably modern for its time.

Later in his career, particularly after his visits to Normandy, his watercolour technique sometimes shifted. He occasionally incorporated richer, deeper colours and experimented with adding substances like rice paste (or flour mixed into a paste) to his watercolours. This created a thicker, more impasto-like texture, allowing for different surface effects and a greater depth of tone, although this technique was used selectively. Throughout, his draughtsmanship remained impeccable, underpinning the structure of his compositions.

Architectural and Antiquarian Interests

A defining feature of Cotman's work is his deep engagement with architecture, particularly the remnants of the medieval past. He travelled extensively in Norfolk, Yorkshire, and later Normandy, meticulously sketching churches, ruined abbeys, castles, and ancient manor houses. This interest aligned with the growing antiquarian and Romantic movements of the period, which celebrated the picturesque beauty of ruins and the nation's history.

His architectural drawings and watercolours are far more than simple records. Works like Walsingham Abbey, Norfolk (1811) or studies of St Botolph's Priory, Colchester demonstrate his ability to capture not just the structural details but also the atmosphere and historical resonance of these sites. He possessed a keen understanding of architectural form and space, often choosing unusual viewpoints or focusing on specific details like doorways or windows to create compelling compositions. The South Door of Thwayt Church (published 1813) is a fine example captured in his etchings.

His trips to Normandy in 1817, 1818, and 1820 were particularly fruitful, resulting in a large body of work documenting the region's magnificent Romanesque and Gothic architecture. These studies formed the basis for another major publication of etchings. His sensitivity to the Gothic Revival style, then gaining momentum, is evident in his respectful and often dramatic portrayals of these historic buildings.

Etching and Printmaking

Cotman was a highly accomplished etcher, and his published prints represent a significant part of his artistic output. Encouraged and financially supported by the Yarmouth banker, botanist, and antiquary Dawson Turner, Cotman embarked on several ambitious series of etchings. The first major series was Architectural Antiquities of Norfolk, published in parts between 1812 and 1818. This comprised meticulously drawn plates showcasing the county's architectural heritage.

His most celebrated print series resulted from his Normandy tours: Architectural Antiquities of Normandy, published in two volumes in 1822 with text provided by Dawson Turner. These etchings are admired for their clarity, precision, and artistic sensitivity. Cotman's linear style proved perfectly suited to rendering architectural detail, while his compositions remained strong and aesthetically pleasing. Other series included Specimens of Norman and Gothic Architecture in the County of Norfolk (1816-1818) and Engravings of Sepulchral Brasses in Norfolk and Suffolk (1819).

While these publications aimed to provide accurate records for antiquarian interest, they are also significant works of art in their own right. Cotman's etchings demonstrate his mastery of line and his ability to convey texture, light, and form through the demanding medium of printmaking. Despite the labour involved and the often poor financial return, these projects cemented his reputation as a serious architectural draughtsman.

Romantic Sensibility

Underlying much of Cotman's work is a Romantic sensibility. While often precise and analytical in his observation, especially of architecture, his landscapes and seascapes frequently possess a powerful mood and atmosphere. He could depict dramatic skies, tranquil riverscapes, and the rugged beauty of coastal scenes with equal skill. Works like Dieppe Harbour show his ability to handle complex scenes with bustling activity, light, and water. His interest in ruins and the passage of time also aligns strongly with Romantic themes prevalent in the art and literature of his contemporaries, such as the poet William Wordsworth or fellow painter John Constable.

Key Works and Commissions

John Sell Cotman's oeuvre is extensive, comprising watercolours, drawings, etchings, and even some oil paintings. Several works stand out as particularly representative of his genius:

Greta Bridge (c. 1805, British Museum): Perhaps his most famous watercolour, epitomizing the clarity, flat washes, and abstract design of his early mature style. It captures the tranquil beauty of the Yorkshire landscape with remarkable economy and elegance.

Chirk Aqueduct (c. 1802-1803, Victoria and Albert Museum): An early masterpiece demonstrating his ability to handle large-scale structures within a landscape setting, showcasing his skill in composition and atmospheric perspective.

Walsingham Abbey, Norfolk (c. 1811, Norwich Castle Museum & Art Gallery / Private Collections): Several versions exist of this subject, showcasing his fascination with Gothic ruins and his ability to render complex architectural detail with sensitivity to light and texture.

The Drop Gate, Duncombe Park (c. 1805, British Museum): Another Yorkshire subject, this watercolour displays the characteristic simplification of form and bold, flat application of colour seen in the Greta series.

Architectural Antiquities of Norfolk (Published 1812-1818): This series of etchings, undertaken with Dawson Turner's support, is a major achievement in architectural recording and printmaking. Key plates include depictions of Castle Acre Priory and Binham Priory.

Architectural Antiquities of Normandy (Published 1822): Containing around 100 etchings, this two-volume work is a monumental record of Norman Romanesque and Gothic architecture, highly valued by both artists and historians.

The Gatehouse, Shute (1802, Yale Center for British Art): An early architectural study showing his developing interest in historical buildings.

Thwayt Church, South Door (Etching, published 1813, Chazen Museum of Art, University of Wisconsin-Madison): A fine example of his detailed architectural etchings from the Norfolk series.

Calcutta (Illustration, Private Collection): Demonstrates his versatility, providing illustrations for publications like Views of the Overland India Route.

Cotman's works are now held in major collections worldwide, including the British Museum, Tate Britain, the Victoria and Albert Museum, the Norwich Castle Museum & Art Gallery (which holds the largest collection), the Yale Center for British Art, and many other public and private collections.

London Again and Later Life

Despite his artistic achievements and local standing, Cotman struggled financially throughout much of his time in Norwich. The market for watercolours was limited, and his published etchings, though critically respected, did not bring substantial income. Seeking better prospects, he successfully applied for the position of Drawing Master at King's College School in London in 1834, thanks partly to the support of J.M.W. Turner.

He moved his family back to London, where he spent the last eight years of his life teaching. While the position provided a regular salary, it was demanding, and London life proved expensive. He continued to paint and draw, but his output perhaps lessened under the pressures of teaching and his recurring struggles with depression. His later watercolours sometimes show a richer, more heavily worked surface, occasionally using the rice paste mixture to achieve textured effects.

In 1836, his expertise in architectural representation was recognized by his election as an Honorary Member of the Institute of British Architects (later RIBA). His sons Miles Edmund and John Joseph assisted him, with Miles eventually succeeding him in the teaching post at King's College after his death. Cotman passed away at his home in Hunter Street, Brunswick Square, London, on July 24, 1842, at the age of 60. He was buried in the cemetery attached to St. John's Wood Chapel, near Lord's Cricket Ground.

Contemporaries and Influence

John Sell Cotman operated within a rich network of artists, patrons, and intellectuals. His most significant artistic connections included:

Thomas Girtin (1775-1802): A foundational influence, particularly on Cotman's early watercolour technique and compositional sense.

J.M.W. Turner (1775-1851): A contemporary and acquaintance from the London sketching club days, and later a supporter. While their styles diverged, they shared a commitment to elevating landscape and watercolour art.

John Crome (1768-1821): The co-founder and leading figure of the Norwich School. Crome's naturalistic, Dutch-influenced style differed from Cotman's more decorative approach, but together they defined the school's identity.

Peter De Wint (1784-1849): A fellow watercolourist with whom Cotman sketched in his early years.

Dawson Turner (1775-1858): A crucial patron, collaborator on the etching publications, and friend, though their relationship was sometimes strained by financial matters.

Sir George Beaumont (1753-1827): An important early patron and influential taste-maker.

Cornelius Varley (1781-1873) & John Varley (1778-1842): Prominent watercolourists and teachers active in London during Cotman's time.

David Cox (1783-1859): Another major figure in the British watercolour school, known for his looser, more atmospheric style.

James Stark (1794-1859) & George Vincent (1796-c.1832): Younger members of the Norwich School, pupils of Crome, who exhibited alongside Cotman.

Miles Edmund Cotman (1810-1858) & John Joseph Cotman (1814-1878): His sons, who carried on the family's artistic tradition, primarily as landscape painters and teachers.

Cotman's direct influence on his immediate contemporaries was perhaps limited by his periods away from London and his unique, somewhat idiosyncratic style. However, his work, particularly the Greta watercolours and the Normandy etchings, was admired by fellow artists. His most significant impact came posthumously.

Legacy and Reputation

During his lifetime, John Sell Cotman's genius was recognized by a discerning few but failed to bring him widespread fame or financial security. His works often sold for low prices, and he constantly battled financial worries and periods of severe depression. His emphasis on flat pattern and simplified form was perhaps too radical for contemporary tastes, which often favoured more detailed picturesque or sublime treatments of landscape.

However, the late 19th and early 20th centuries saw a dramatic reassessment of his work. Critics and collectors began to appreciate the modernity of his vision, his exceptional design sense, and his mastery of watercolour. Figures like Laurence Binyon, a curator at the British Museum, championed his work. Cotman came to be regarded not just as a key member of the Norwich School, but as one of the most original and important figures in British art history.

His Greta Bridge phase, in particular, is now seen as a pinnacle of watercolour painting, admired for its lyrical beauty and formal innovation. Some critics have even placed his finest watercolours on a par with, or offering a distinct but equally valuable alternative to, the work of J.M.W. Turner, praising Cotman's unique feeling for structure and decoration. His architectural etchings remain highly respected for their accuracy and artistry. Today, he is firmly established as a major master, whose work continues to inspire admiration for its elegance, emotional depth, and technical brilliance.

Conclusion

John Sell Cotman's art offers a unique synthesis of careful observation, particularly of architecture and the Norfolk landscape, and a sophisticated, almost abstract sense of design. A master of both the broad wash and the precise line, he excelled in watercolour and etching, creating works that are both topographically informative and aesthetically compelling. As a leading member of the Norwich School, he brought a distinctive vision to the depiction of his native region. Though hampered by personal struggles and a lack of widespread contemporary recognition, his posthumous reputation has rightly placed him among the foremost British artists of the 19th century. His legacy lies in a body of work characterized by its clarity, elegance, and profound sensitivity to pattern, colour, and form.