Introduction: Bridging Worlds Through Art

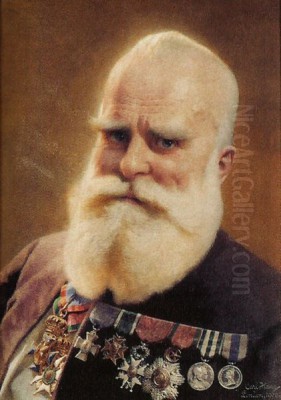

Carl Haag stands as a fascinating figure in nineteenth-century European art, a bridge between the artistic traditions of Germany and Britain, and between the landscapes of Europe and the allure of the Orient. Born in Bavaria, he achieved his greatest fame after adopting British nationality, becoming one of the most accomplished and sought-after watercolour painters of the Victorian era. Renowned particularly for his vibrant and meticulously detailed Orientalist scenes, Haag captured the imagination of the public and earned the patronage of the highest echelons of society, including Queen Victoria herself. His life and work offer a compelling insight into the artistic exchanges, cultural fascinations, and technical developments of his time.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Germany

Johann Carl Haag was born on April 20, 1820, in Erlangen, within the Kingdom of Bavaria. His artistic inclinations emerged early, leading him to pursue formal training first in Nuremberg. He enrolled at the Academy of Fine Arts Nuremberg, a respected institution where he began honing his skills. During this formative period, he studied under influential figures of the German art scene, absorbing the prevailing currents of Romanticism and historical painting.

Following his studies in Nuremberg, Haag moved to Munich, then a major artistic centre in Germany. He continued his education there, further refining his technique, particularly in oil painting. His early works primarily focused on portraiture and architectural subjects, demonstrating a strong grasp of form, detail, and composition. Key mentors during his German training included Peter von Cornelius and Wilhelm von Kaulbach, leading figures associated with the Nazarene movement and monumental historical painting, and Carl Rottmann, known for his landscape cycles. This grounding in the German academic tradition provided Haag with a solid technical foundation before his pivotal move abroad.

The Move to England and Mastery of Watercolour

A significant turning point in Haag's career occurred in 1847 when he decided to move to England. His primary motivation was to immerse himself in and master the distinct techniques of English watercolour painting, a medium that enjoyed exceptional prestige and development in Britain at the time. He sought to learn from the tradition established by masters like J.M.W. Turner, David Cox, and Peter De Wint, whose works demonstrated the expressive potential and luminosity of watercolour.

Upon arriving in London, Haag furthered his studies, including time spent at the Royal Academy Schools. He dedicated himself to understanding the nuances of the medium, experimenting with washes, layering, and techniques for achieving transparency and brilliance. His aptitude was quickly recognized. He began exhibiting his watercolours and swiftly gained acceptance within the British art establishment.

His skill led to his election as an Associate of the prestigious Society of Painters in Water Colours (often known as the Old Watercolour Society or OWS, later RWS) in 1850. His full membership followed just three years later, in 1853, cementing his position among the leading watercolourists in his adopted country. This transition marked a definitive shift in his artistic focus, with watercolour becoming his primary medium for the remainder of his long career.

Royal Patronage and Esteem

Haag's talent and personable nature soon brought him to the attention of the British Royal Family. A chance encounter in the Tyrol in 1852 proved highly fortuitous. While sketching, he met Charles, Prince of Leiningen (Queen Victoria's half-brother) and Ernest II, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (Prince Albert's brother). Impressed by his work, they jointly commissioned Haag to paint a scene of the Tyrolean Alps – specifically depicting the Jagdschloss St. Martin bei Lofer – intended as a Christmas gift for Queen Victoria and Prince Albert.

This commission opened the doors to significant royal patronage. Queen Victoria and Prince Albert were greatly pleased with the gift and became consistent admirers and patrons of Haag's work. He received numerous commissions from the royal couple, including portraits of members of the royal family and depictions of significant events or favoured locations, such as Balmoral Castle in Scotland. His works were acquired for the Royal Collection, with many still housed in the Royal Library at Windsor Castle today.

His connection to German royalty also continued; he held the position of Court Painter to the reigning Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha. This dual patronage, from both British and German royalty, underscored his unique position and the high esteem in which his art was held. The Queen's favour, in particular, significantly boosted his reputation and desirability among collectors in Britain.

The Call of the East: Travels and Orientalism

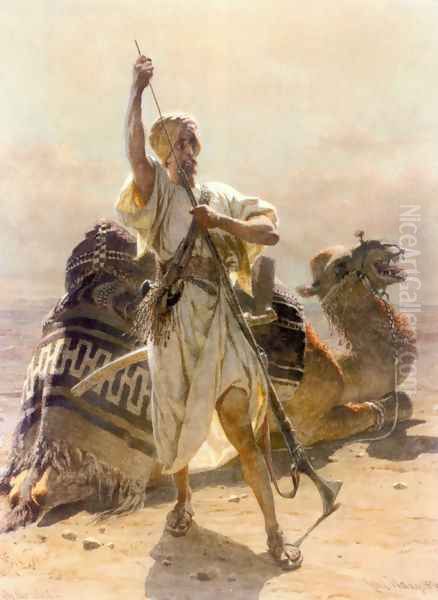

Like many European artists of the nineteenth century, Carl Haag felt the powerful allure of the 'Orient' – a term then used broadly to encompass North Africa, the Middle East, and sometimes parts of Asia. This fascination, fueled by colonial expansion, increased travel, archaeological discoveries, and romantic literature, gave rise to the popular genre of Orientalist painting. Haag became one of its most accomplished practitioners in watercolour.

Between 1858 and 1860, Haag embarked on an extensive and transformative journey through the Middle East. This two-year expedition took him to Egypt, up the Nile, across the deserts to Syria, through Lebanon, and into Palestine, visiting Jerusalem and Palmyra. This was not a fleeting tour but an immersive experience. He sought direct contact with the landscapes, architecture, and people he wished to depict.

During part of this journey, particularly in Cairo, he shared lodgings and experiences with the English painter Frederick Goodall, another artist captivated by Egyptian subjects. They lived for a time in the Coptic Quarter of Cairo, sketching and gathering material. Haag even spent several months living in a tent in the desert near Giza, an experience he described as deeply rewarding, allowing him to observe the nuances of desert light and Bedouin life firsthand. This dedication to direct observation lent an air of authenticity to his subsequent works.

The sketches, studies, and memories gathered during this period provided Haag with a rich repository of subject matter that would dominate his output for decades. He joined a lineage of artists drawn to the East, including the earlier Scottish painter David Roberts, known for his monumental lithographs of Egypt and the Holy Land, and contemporaries like the meticulous English watercolourist John Frederick Lewis, who had lived extensively in Cairo, and the French academic painter Jean-Léon Gérôme. Haag's approach, however, focused on the brilliance and detail achievable in watercolour.

Artistic Style and Technique

Carl Haag's mature style is characterized by its remarkable technical proficiency in watercolour, combined with a sensibility that blended Romanticism with a Victorian taste for detail and narrative. His mastery of the watercolour medium was exceptional. He employed a range of techniques, from broad, luminous washes for skies and backgrounds to incredibly fine brushwork for rendering textures, architectural details, and human figures.

His Orientalist works are particularly noted for their vibrant colour palettes, capturing the intense light and hues of the Middle Eastern sun. He skillfully depicted the interplay of light and shadow, creating dramatic contrasts and a strong sense of atmosphere, whether rendering the cool interior of a mosque, the dazzling exterior of a desert ruin, or the bustling activity of a bazaar. There is often a heightened sense of realism in his work, striving for ethnographic and architectural accuracy based on his travels and sketches.

While rooted in observation, his paintings were not mere topographical records. They often incorporated elements of Romanticism – a sense of the sublime in depicting ancient ruins, a fascination with the exotic 'other', and sometimes a narrative or anecdotal quality in his genre scenes. He depicted not only grand vistas and monuments but also intimate scenes of daily life, Bedouin encampments, portraits of local people, and detailed studies of costumes and artefacts. His ability to render complex scenes with clarity and precision, while maintaining painterly qualities, set him apart.

Compared to some Orientalists who emphasized the sensuous or dramatic, Haag's work often possessed a certain dignity and careful observation. His approach shares affinities with John Frederick Lewis in its meticulous detail, though perhaps with a slightly broader handling of landscape elements. Unlike the grander, often oil-based historical or allegorical scenes of French Orientalists like Eugène Delacroix or Gérôme, Haag's strength lay in the specific possibilities of watercolour – its transparency, brilliance, and capacity for intricate detail on a sometimes more intimate scale.

Key Works and Themes

Throughout his long career, Carl Haag produced a substantial body of work, with his Orientalist subjects being the most celebrated. Several paintings stand out as representative of his style and interests:

The Ruins of the Temple of the Sun, Palmyra (1859): Painted following his visit to the ancient Syrian site, this work exemplifies his ability to capture the grandeur and atmospheric decay of historical ruins under the desert sun. The meticulous rendering of the classical architecture contrasts with the vastness of the surrounding landscape, evoking a sense of history and the passage of time.

The Dome of the Rock, Jerusalem: Haag painted several views of this iconic structure and the Temple Mount. These works showcase his skill in architectural depiction and his sensitivity to the spiritual significance of the site. He carefully rendered the intricate tilework and golden dome, often including figures to provide scale and context, capturing the unique light of Jerusalem.

Danger in the Desert and The Alert: These paintings depict dramatic moments of Bedouin life, showcasing Haag's interest in the people of the regions he visited. They often feature carefully observed details of costume, weaponry, and Arabian horses, set against expansive desert backdrops. These works catered to the Victorian appetite for exotic adventure and narrative.

An Audience at the Threshold of the Temple of Amun, Karnak: This work combines architectural grandeur with a depiction of ancient Egyptian religious practice, reflecting the widespread contemporary interest in Egyptology sparked by archaeological discoveries.

Happiness and Grief (or similar titles depicting contrasting emotions): Haag also painted genre scenes exploring universal human emotions, often set within Middle Eastern interiors or courtyards. These allowed him to display his skill in figure painting and detailed rendering of domestic settings.

Beyond his Orientalist works, Haag continued to paint European subjects, particularly landscapes and architectural views from his travels in Italy, Greece, the Tyrol, and his native Germany. An early example is The Red Tower at Oberwesel (1850), a depiction of a landmark in the Rhine Valley town where he would eventually settle. He also remained an accomplished portraitist throughout his career, fulfilling commissions from both royal and private clients. His diverse output reflects his broad artistic interests and technical versatility.

Context and Contemporaries

Carl Haag operated within a vibrant and complex Victorian art world. His success in Britain coincided with the peak of the British Empire and a corresponding public fascination with its territories and spheres of influence, including the Middle East. Orientalism was a dominant theme not only in painting but also in literature, design, and popular culture. Haag's work resonated strongly with this interest.

He was a prominent member of the Royal Society of Painters in Water Colours during a period when the medium was highly valued. He exhibited regularly alongside other leading watercolourists of the day. His meticulous style found favour during an era influenced by the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood's emphasis on truth to nature and detailed rendering, although Haag was not formally associated with the group. Figures like William Holman Hunt, a core member of the Pre-Raphaelites, also travelled to the Middle East, seeking authenticity for his religious paintings, providing an interesting parallel to Haag's journeys.

His direct collaborator, Frederick Goodall, became similarly known for his large-scale oil paintings of Egyptian subjects, often more anecdotal and picturesque than Haag's detailed watercolours. The influence of the critic John Ruskin, who championed detailed observation and truthfulness in art, can perhaps be seen indirectly in the appreciation for Haag's careful style, even though Ruskin's primary focus was often on artists like Turner or the Pre-Raphaelites.

In the broader European context, Haag's Orientalism can be situated alongside the work of French artists like Jean-Léon Gérôme, whose highly finished academic paintings often depicted historical or sensualized scenes of the East, and earlier Romantics like Eugène Delacroix, whose visits to North Africa had profoundly influenced his colour and subject matter. Haag's German contemporaries included history painters like his former teachers Cornelius and Kaulbach, and realists like Adolph Menzel, though Haag's career path diverged significantly after his move to Britain. His unique position stemmed from his German training combined with his mastery of the English watercolour tradition and his focus on Orientalist themes, facilitated by royal patronage.

Later Life and Legacy

After a long and successful career based primarily in London, Carl Haag eventually decided to return to Germany. In 1903, he retired to Oberwesel am Rhein, a picturesque town he had painted earlier in his career. There, he built a distinctive residence known as the 'Tower House' (Turmhaus), incorporating a medieval defensive tower, overlooking the Rhine River.

He continued to be active, though less prolific, in his later years. Carl Haag passed away in Oberwesel on January 24, 1915, at the venerable age of 94. By the time of his death, the art world was already undergoing radical transformations with the advent of modernism, moving away from the detailed realism and narrative interests of the Victorian era.

Despite shifts in artistic taste, Carl Haag left a significant legacy. He remains one of the foremost watercolour painters of the Victorian period, particularly celebrated for his contributions to the Orientalist genre. His works are valued for their technical brilliance, their detailed documentation of Middle Eastern landscapes, architecture, and life as observed in the mid-nineteenth century, and their embodiment of the Victorian fascination with the exotic.

While perhaps less known in his native Germany compared to his high standing in Britain, his paintings continue to be sought after by collectors and are represented in major public collections, including the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, the British Museum, and, notably, the Royal Collection Trust. His life story exemplifies the transnational nature of artistic careers in the nineteenth century and the enduring appeal of masterful technique applied to captivating subject matter.

Conclusion: An Enduring Vision

Carl Haag's journey from the academies of Bavaria to the heart of the London art world and the deserts of the Middle East resulted in a unique and enduring body of work. As a master watercolourist, he pushed the boundaries of the medium, achieving remarkable levels of detail, luminosity, and atmospheric effect. His Orientalist paintings, born from direct experience and meticulous observation, provided his Victorian audience with vivid glimpses into lands that seemed both remote and captivatingly immediate through his art. Supported by royal favour and admired for his technical skill, Haag secured a prominent place in nineteenth-century British art. Today, his works continue to be appreciated not only as beautiful objects but also as valuable historical documents reflecting the cultural exchanges and artistic preoccupations of his era. He remains a testament to the power of dedicated craftsmanship and the enduring human fascination with exploring and representing the wider world.