William Egley, born in 1798 and passing away in 1870, was a distinguished English artist who carved a significant niche for himself in the bustling art world of 19th-century Britain. Primarily celebrated as a portrait painter, he demonstrated exceptional skill in the delicate art of watercolour and miniature painting. His life and career unfolded during a period of profound social, industrial, and artistic transformation, an era that saw the rise of the middle class, the burgeoning influence of the Royal Academy, and the emergence of new artistic movements that challenged established conventions. Egley's work, while perhaps not as revolutionary as some of his contemporaries, offers a valuable window into the tastes, aspirations, and intimate lives of the Victorian people he depicted.

Early Life and Artistic Inclinations

Details regarding William Egley's formal artistic education are not extensively documented in readily available sources. However, it was common during this period for aspiring artists to receive training through apprenticeships with established masters, by attending drawing schools, or, for the more privileged or determined, by enrolling in the prestigious Royal Academy Schools in London. Given his proficiency in miniature painting, a highly specialized skill, it is likely he received dedicated instruction in this demanding field. The late 18th and early 19th centuries still held miniature painting in high regard, a tradition carried forward from luminaries like Nicholas Hilliard and Samuel Cooper in earlier centuries.

Egley emerged as an artist at a time when portraiture was a dominant genre, fulfilling a societal need for likenesses before the widespread availability and affordability of photography. The demand for portraits, ranging from grand oil paintings to intimate miniatures, was robust, fueled by royalty, aristocracy, and the increasingly affluent merchant and professional classes. Egley chose to specialize in a more personal and portable form of this art.

The Delicate Art of Miniature Painting

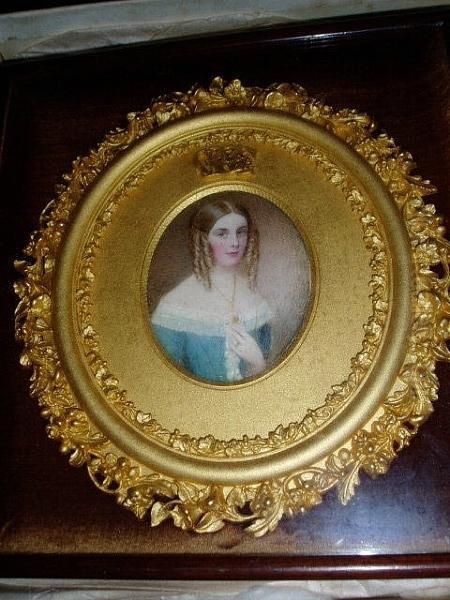

Miniature painting, particularly on ivory, was a highly respected art form in the 18th and early 19th centuries, and William Egley excelled in this medium. This practice required immense patience, a steady hand, and an acute eye for detail. Artists like Richard Cosway and George Engleheart had set a high standard in the preceding generation. Miniatures served as cherished keepsakes, often exchanged as tokens of affection or remembrance, easily carried on one's person or displayed in intimate settings.

Egley's miniatures were typically executed in watercolour on ivory, a surface that lent a unique luminosity and smoothness to the finished piece. The translucency of the ivory allowed light to pass through the watercolour pigments, giving the portraits a delicate, lifelike glow. He would have employed fine brushes, possibly made from sable, to apply tiny strokes and stipples of colour, meticulously building up the likeness and capturing the subtle nuances of his sitters' features and expressions. The intimate scale of these works demanded precision, as any flaw would be readily apparent.

Notable Works and Stylistic Traits

William Egley's oeuvre, as indicated by surviving examples and records, primarily consisted of portraits, with a particular focus on children and family groups. These subjects were popular in the Victorian era, reflecting the period's emphasis on domesticity and the sentimental view of childhood.

One of his documented works is the "Portrait of Fitzroy Augustus Talbot," painted in 1837. This piece, likely a miniature, would have showcased Egley's ability to capture not only a physical likeness but also a sense of the sitter's personality, a crucial element in successful portraiture. The depiction of children required a particular skill, as artists needed to convey their youthful innocence and vitality while also managing the practical challenges of a young, often restless, sitter.

Another example is the "Portrait of the children of Richard Nugent Clayton and Maria Clayton," dated 1839. Group portraits, especially of children, presented complex compositional challenges. Egley would have needed to arrange the figures harmoniously, create a sense of interaction or shared space, and ensure each child's individuality was preserved. Such commissions underscore the trust families placed in his ability to create lasting and endearing records of their loved ones.

His 1864 portrait of "John Lort Stokes" demonstrates his continued practice later in his career. Stokes was a notable figure, an admiral in the Royal Navy known for his survey work. Portraying such a distinguished individual would have required Egley to convey a sense of authority and accomplishment, alongside the physical likeness.

A work titled "Unknown Girl," dated 1832 and housed in the Swedish National Museum, further attests to his skill. The very existence of such a piece in a significant European collection speaks to the quality and appeal of his art beyond British shores, or perhaps to the travels and connections of its original owner. The "classical elegance" noted in such works suggests an adherence to established aesthetic principles, emphasizing grace, balanced composition, and a refined finish.

Egley's style can be characterized by its meticulous detail, delicate application of colour, and a sensitive approach to capturing the human face and form. His watercolours on ivory would have possessed a characteristic softness and luminosity, distinct from the bolder effects achievable with oil on canvas. He aimed for verisimilitude, but also for a pleasing and often gentle representation of his subjects.

Patronage and the Social Milieu

The patrons of artists like William Egley were typically members of the gentry, the burgeoning middle class, and occasionally the aristocracy. These individuals sought portraits for various reasons: to commemorate important life events, to display their status and familial pride, or simply to have a tangible image of beloved family members. Miniatures were particularly popular as personal mementos, often set into lockets, brooches, or small, ornate frames.

The Victorian era, with its strong emphasis on family values, provided a fertile ground for artists specializing in portraits of children and domestic scenes. Egley's focus on these themes placed him squarely within the prevailing tastes of his time. His clients would have appreciated the charm and intimacy of his work, which offered a more personal alternative to the grander, more formal portraits executed by artists like Sir Thomas Lawrence or, later in the century, Franz Xaver Winterhalter, who was a favourite of Queen Victoria.

While Egley may not have catered to the highest echelons of royalty in the same way as Winterhalter, his clientele would have been substantial and respectable, providing him with a steady stream of commissions. The act of commissioning a portrait was in itself a statement of a certain social standing and cultural aspiration.

Exhibitions and Professional Recognition

For an artist in 19th-century Britain, exhibiting work was crucial for gaining recognition, attracting patrons, and establishing a professional reputation. The most prestigious venue was the Royal Academy of Arts in London, whose annual Summer Exhibition was a major event in the social and artistic calendar. Other exhibiting societies, such as the Society of British Artists (founded in 1823), also provided platforms for artists.

While the provided information focuses more on his son's exhibition record, it is highly probable that William Egley (1798-1870) also exhibited his works regularly. Portraitists, especially those specializing in miniatures, frequently submitted their pieces to these exhibitions. The catalogues of the Royal Academy and other societies from this period would likely list his contributions, offering further insight into the scope of his practice and the types of portraits he was producing at different stages of his career. Success in these exhibitions could lead to critical acclaim, new commissions, and an enhanced standing within the artistic community. Artists like Sir Martin Archer Shee, who became President of the Royal Academy, built their careers through consistent and well-received exhibition entries.

The Artistic Legacy: His Son, William Maw Egley

William Egley's artistic lineage was notably continued through his son, William Maw Egley (1826-1916). The younger Egley also became a respected artist, though his thematic concerns and stylistic approaches differed somewhat from his father's. This familial connection is significant, as artistic skills and inclinations were often passed down within families, with fathers frequently providing initial training to their sons.

William Maw Egley is known for his detailed genre scenes, often depicting contemporary urban life and literary subjects. His most famous work is arguably "Omnibus Life in London" (1859), now in the Tate collection. This painting is a vibrant and meticulously observed depiction of the diverse array of passengers crammed into a horse-drawn omnibus, offering a fascinating snapshot of Victorian society. The attention to costume, social interaction, and individual characterization is remarkable. This painting showcases a different sensibility than his father's more intimate portrait miniatures, engaging with broader social narratives and the hustle and bustle of modern life.

The younger Egley was also associated with "The Clique," a group of artists formed in the late 1830s and early 1840s. Key members included Richard Dadd, Augustus Egg, Alfred Elmore, William Powell Frith, and Henry Nelson O'Neil. The Clique reacted against what they perceived as the overly academic and high-minded idealism of the Royal Academy, advocating instead for subjects drawn from everyday life and popular literature, often with a narrative or anecdotal quality. William Powell Frith, for instance, became hugely popular for his panoramic scenes of modern life, such as "Derby Day" and "The Railway Station." William Maw Egley's interest in contemporary scenes and literary illustrations aligns with the general ethos of The Clique.

Furthermore, William Maw Egley's work shows an awareness of, and perhaps influence from, the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (PRB), which emerged in 1848. Though not a member, his paintings sometimes exhibit the bright colours, sharp focus, and attention to detail characteristic of PRB artists like John Everett Millais, William Holman Hunt, and Dante Gabriel Rossetti. His painting "The Talking Oak" (1857) is one such example. The PRB sought to revitalize British art by rejecting the perceived artificiality of academic painting and drawing inspiration from early Renaissance art.

William Maw Egley also reportedly designed one of the earliest Christmas cards in 1842, a pencil sketch for which is held in the Victoria and Albert Museum. This anecdote, placing him alongside Sir Henry Cole who is more famously credited with popularizing the Christmas card around 1843, highlights his engagement with emerging popular visual culture.

The career of William Maw Egley, therefore, demonstrates a progression and adaptation to the changing artistic landscape of the mid to late Victorian period, moving from the more traditional portraiture of his father towards genre painting and narrative art, influenced by contemporary movements and a keen observation of modern life.

The Broader Artistic Context of 19th-Century Britain

William Egley (1798-1870) worked during a dynamic period in British art. The early part of his career coincided with the tail end of the Regency and the ascendancy of Romanticism, with giants like J.M.W. Turner and John Constable revolutionizing landscape painting. Portraiture continued to be dominated by figures who followed in the grand tradition of Sir Joshua Reynolds and Thomas Gainsborough. Sir Thomas Lawrence was the pre-eminent portrait painter at the start of Egley's career.

The Victorian era proper, which began in 1837, saw a flourishing of diverse artistic styles. The Royal Academy remained a powerful institution, but it also faced challenges from artists seeking new modes of expression. Genre painting, depicting scenes of everyday life, gained immense popularity, with artists like David Wilkie achieving widespread acclaim even before the Victorian era, paving the way for later artists like Frith.

The rise of an affluent middle class created new markets for art. This class often favoured subjects they could relate to: domestic scenes, narrative paintings with clear moral or sentimental messages, and portraits that were less about aristocratic grandeur and more about personal identity and familial affection. Egley's specialization in portrait miniatures and family groups catered well to this sensibility.

The invention and increasing accessibility of photography from the 1840s onwards began to impact the field of portraiture. While photography offered a quicker and often cheaper means of obtaining a likeness, painted and drawn portraits, especially miniatures, retained a certain prestige and artistic value. Many artists, however, had to adapt to this new technology, some even using photographs as aids for their painted portraits. For miniaturists like Egley, the challenge was perhaps more direct, as photography could fulfill the desire for small, portable likenesses. Nevertheless, the unique artistry and personal touch of a hand-painted miniature continued to appeal to many.

Later in Egley's career, movements like the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood introduced radical new ideas about truth to nature, detail, and subject matter, often drawing from literature, religion, and medieval themes. While Egley Sr.'s primary focus remained on portraiture, the artistic environment around him was one of constant debate and innovation.

Later Career and Enduring Significance

William Egley continued to practice his art throughout the mid-19th century. As photography became more established, the demand for portrait miniatures may have waned somewhat, but skilled practitioners like Egley would likely have retained a loyal clientele who appreciated the artistry and unique charm of a hand-painted likeness. His portrait of John Lort Stokes in 1864, when Egley was in his mid-sixties, indicates his continued activity.

His enduring significance lies in his contribution to the tradition of British portraiture, particularly in the specialized field of miniature painting. His works serve as valuable historical documents, offering glimpses into the appearance and lives of individuals from the Victorian era. They are testaments to his technical skill, his sensitivity as a portraitist, and the enduring human desire to capture and preserve the image of loved ones.

While he may not have achieved the same level of fame as some of his more revolutionary contemporaries or even his son, William Maw Egley, whose "Omnibus Life in London" became an iconic image of Victorian urban life, William Egley Sr. played an important role within his specific domain. He represented a high standard of craftsmanship in a demanding art form, and his portraits continue to be appreciated for their delicacy, precision, and intimate charm.

His legacy is twofold: firstly, through his own body of work, which provides a visual record of his sitters and exemplifies the art of watercolour miniature painting in the 19th century; and secondly, through his son, William Maw Egley, who built upon the artistic foundation, likely received from his father, to become a notable painter in his own right, engaging with different themes and artistic currents.

Conclusion

William Egley (1798-1870) stands as a noteworthy figure in the landscape of 19th-century British art. As a specialist in portraiture, particularly watercolour miniatures on ivory, he catered to a societal need for personal and familial likenesses during an era of significant social change. His works, characterized by meticulous detail, delicate execution, and a sensitive portrayal of his subjects, especially children, reflect the tastes and values of the Victorian period.

While the grand narratives of art history often focus on groundbreaking movements and monumental works, the contributions of skilled practitioners like Egley, who excelled in more intimate and specialized genres, are essential for a complete understanding of the artistic ecosystem of their time. His portraits of figures like Fitzroy Augustus Talbot and John Lort Stokes, alongside numerous depictions of families and children, form a valuable part of Britain's visual heritage. Through his art, and through the subsequent artistic career of his son William Maw Egley, his name remains connected to the rich tapestry of Victorian art, a testament to a life dedicated to the careful and affectionate rendering of the human face.