The name Hopkins resonates through various annals of history, from the rigorous corridors of science and mathematics to the expressive realms of poetry and the visual arts. When seeking to understand "William H. Hopkins" as a painter, we embark on a fascinating journey that uncovers not one, but several individuals who bore this or a similar name, each contributing to the cultural tapestry of their times in unique ways. This exploration will delve into the life of the notable William H. Hopkins, a man of science with an appreciation for the arts, and expand to encompass other Hopkins figures, particularly Gerard Manley Hopkins, whose poetic vision was intensely visual, and Milton W. Hopkins, an American painter, to paint a fuller picture of the artistic currents associated with the name.

William H. Hopkins: A Man of Science with an Artistic Soul

Born on February 2, 1793, in Kingston-on-Soar, Nottinghamshire, England, William H. Hopkins was a figure of considerable intellectual prowess, primarily known for his contributions as a mathematician and geologist. His academic journey led him to Peterhouse, Cambridge, where he distinguished himself. He earned the moniker "senior wrangler-maker" or "senior wrangler" due to his exceptional ability to tutor students to achieve the highest academic honors in mathematics at Cambridge. This reputation as an educator was formidable, shaping many young minds who would go on to make their own significant contributions.

Hopkins's scientific inquiries were groundbreaking. He made significant strides in geology, particularly in understanding the physical processes shaping the Earth. One of his most notable scientific achievements was the discovery that the melting point of substances increases with pressure. This finding had profound implications for understanding the Earth's internal structure and dynamics. His work in this area was recognized with the Wollaston Medal from the Geological Society of London in 1850, a prestigious award acknowledging outstanding research in geology. He was also a Fellow of the Royal Society, further testament to his scientific standing.

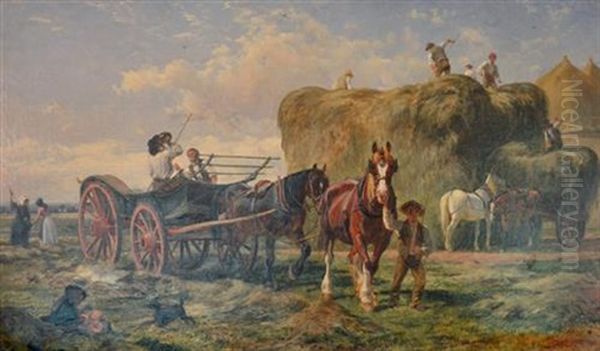

While his professional life was steeped in numbers and geological strata, William H. Hopkins harbored a deep appreciation for the arts. Records indicate he had a keen interest in music, poetry, and notably, landscape painting. This interest suggests a multifaceted personality, one that could navigate the logical rigors of science while also finding solace and inspiration in aesthetic pursuits. Though he is not primarily remembered as a practicing artist with a significant body of exhibited work, his engagement with landscape painting points to a sensitivity towards the visual representation of the natural world – a world he meticulously studied as a geologist.

His personal life saw him marry twice. His first wife passed away in 1821. He later married Caroline Frances Boys, a woman known for her work as a moral reformer. Together, they had four children. Hopkins was also an active individual in his youth, participating in first-class cricket matches for Cambridge University between 1825 and 1828. However, his later years were marked by considerable struggle. He suffered from chronic anxiety and exhaustion, conditions that ultimately led to his admission to a private mental hospital in Stoke Newington, London. William H. Hopkins passed away there on October 13, 1866. While his primary legacy is scientific, his documented interest in landscape painting provides a crucial link to the broader artistic currents of his time, an era dominated by Romantic painters like J.M.W. Turner and John Constable, who revolutionized the depiction of the British landscape.

Gerard Manley Hopkins: The Poet with a Painter's Eye

While William H. Hopkins the mathematician had an appreciation for art, another Hopkins, Gerard Manley Hopkins (1844-1889), though primarily a poet, possessed an intensely visual imagination and a distinct artistic style that often translated into "word-painting." His connection to the visual arts was profound, influencing his unique poetic language and his own forays into sketching.

Born in Stratford, Essex, Gerard Manley Hopkins was a Victorian poet whose work, largely unpublished during his lifetime, gained significant recognition posthumously. He converted to Roman Catholicism and became a Jesuit priest, and his deep religious faith permeated his poetry. His artistic sensibilities were shaped early on, partly through his family background – his father published poetry, and his uncle was an artist. He studied Classics at Balliol College, Oxford, where he was influenced by the aesthetic theories of John Ruskin and the art of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, which included painters like Dante Gabriel Rossetti, John Everett Millais, and William Holman Hunt.

Hopkins's poetry is renowned for its innovative use of rhythm, which he termed "sprung rhythm," and its rich, dense soundscapes created through techniques like "chiming consonants" (alliteration and assonance). His aim was to capture the unique essence or "inscape" of a thing – its individual, distinctive design or pattern – and the divine energy or "instress" that upholds it. This pursuit of "inscape" is inherently visual. Poems like "Pied Beauty," "The Windhover," and "God's Grandeur" are celebrated for their vivid imagery and their almost tactile descriptions of nature. "God's Grandeur," for instance, speaks of the world being "charged with the grandeur of God," a line that evokes a powerful visual and sensory experience.

His journals and letters reveal a keen observer of the natural world, meticulously recording details of cloud formations, water patterns, and plant structures. These observations often found their way into his delicate and precise sketches. While not a professional painter, his drawings, often of natural subjects, demonstrate a fine hand and a deep understanding of form and light, akin to the detailed naturalism advocated by Ruskin. He saw a strong connection between poetry and painting, once writing, "Poetry is speech framed … to be heard for its own sake and interest even over and above its interest of meaning. Some matter and meaning is essential to it but only as an element necessary to support and employ it." He believed in "painting with sound," using the musicality of language to evoke visual scenes.

The influence of visual art on his poetry is undeniable. He admired the work of early Renaissance painters and the detailed realism of the Pre-Raphaelites. His concept of "inscape" can be seen as a literary parallel to the Pre-Raphaelites' desire to capture the truth of nature with utmost fidelity. His unique style, though challenging to his contemporaries, has made him a significant figure in English literature, often seen as a bridge between Victorian poetry and modernism. His ability to translate visual perception into verbal art marks him as a unique artistic voice, one whose poetic "canvases" are as rich and detailed as any painting. His students, such as Edward John Roche and Francis, were undoubtedly influenced by his passionate engagement with both language and the visual world.

Milton W. Hopkins: An American Painter and Craftsman

Across the Atlantic, another Hopkins made his mark in the visual arts: Milton W. Hopkins (active c. 1820s-1840s). While less globally renowned than Gerard Manley Hopkins, Milton W. Hopkins was a practicing artist in 19th-century America, known primarily as a portrait and decorative painter. His career provides insight into the life of an artist-craftsman during a period of significant growth and cultural development in the United States.

Information about Milton W. Hopkins suggests he was a versatile artisan. He was active in areas like Richmond, Virginia, and parts of Ohio. His work encompassed not only portraiture, which was in high demand in the burgeoning republic, but also decorative painting, furniture making, gilding, and even glass sales. This range of skills was common for artists of the period, who often needed to be adaptable to make a living. Portraitists like Gilbert Stuart and Thomas Sully set a high bar, but regional painters like Milton Hopkins played a crucial role in documenting the citizenry and beautifying homes.

As a decorative painter, Milton W. Hopkins would have been involved in a variety of tasks, from painting ornamental designs on walls, furniture, and other objects to creating signage. This field of art was vital to the aesthetic life of communities, bringing color and artistry into everyday spaces. The tradition of itinerant painters was strong in America, with artists traveling from town to town, offering their services. While specific "masterpieces" by Milton W. Hopkins may not be widely cataloged in major museum collections today, his contribution lies in the broader context of American folk art and decorative traditions. His portraits would have aimed to capture a likeness, often with a directness and simplicity characteristic of provincial American painting of the era, distinct from the more academic styles of European-trained artists like John Singleton Copley (though Copley was earlier, his influence lingered).

The environment in which Milton W. Hopkins worked was one where the distinctions between "fine art" and "craft" were more fluid than they are today. An artist who could paint a portrait, decorate a chest, gild a frame, and perhaps even letter a sign was a valuable member of the community. His work would have been part of a visual culture that included not only formal paintings but also a wide array of handcrafted and decorated objects. Understanding his career requires appreciating the practical demands and diverse opportunities available to artists in 19th-century America, a context shared by other versatile artists and craftsmen of the time. He represents a segment of the art world that was essential to the cultural fabric, even if not always recorded with the same prominence as academy painters.

James R. Hopkins: Chronicler of Appalachian Life

Further into the American art narrative, we encounter James R. Hopkins (1877-1969), an American painter who, in the early 20th century, became known for his sensitive portrayals of the people of the Appalachian and Cumberland Mountain regions. Though from a later period, his work continues the tradition of American artists engaging with regional identities and everyday life.

James Roy Hopkins studied at the Art Academy of Cincinnati and later in Paris under James Abbott McNeill Whistler. This training provided him with a sophisticated technique, which he then applied to subjects that were distinctly American. After spending time in Paris and working as an art professor, he and his wife, the artist Edna Boies Hopkins, moved to Mechanicsburg, Ohio, and he began to focus on the Cumberland region of Kentucky.

His paintings of the mountain people are characterized by their dignity and realism, avoiding caricature or sentimentality. Works like "The Mountain Preacher" or "A Kentucky Mountaineer" showcase his ability to capture the character and resilience of his subjects. He was part of a broader movement of American Scene Painting that gained prominence in the 1920s and 30s, which included artists like Thomas Hart Benton, Grant Wood, and John Steuart Curry, all of whom sought to create a distinctly American art by depicting scenes of rural and small-town life. James R. Hopkins's contribution was his focus on a specific, often overlooked, region, bringing its people and their culture to a wider audience with empathy and artistic skill. His style often incorporated a rich use of color and a strong sense of design, reflecting his academic training yet applied to uniquely American themes.

The Victorian and Early Modern Artistic Milieu: Context for the Hopkins Figures

The various Hopkins figures with artistic connections operated within rich and evolving artistic landscapes. William H. Hopkins, the mathematician with an interest in landscape painting, lived through the peak of British Romanticism and the rise of Victorian art. The era saw landscape painting elevated to new heights by Turner and Constable. The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, formed in 1848, challenged the Royal Academy's dominance, advocating for a return to the detailed realism and vibrant color of Quattrocento Italian art. Figures like Ford Madox Brown and later Edward Burne-Jones and William Morris (who championed the Arts and Crafts Movement) further diversified the artistic scene.

Gerard Manley Hopkins, the poet, was a direct contemporary of the later Pre-Raphaelites and the Aesthetic Movement, which emphasized "art for art's sake," championed by figures like Whistler. His own visual sensibilities were clearly informed by Ruskin's emphasis on truth to nature and the detailed observation practiced by the Pre-Raphaelites. The Victorian era was a period of intense debate about the role and purpose of art, with science, religion, and industrialization all shaping cultural discourse.

In America, Milton W. Hopkins worked during a period of national formation and expansion. The Hudson River School, featuring artists like Thomas Cole and Asher B. Durand, was establishing a tradition of American landscape painting, celebrating the grandeur of the New World. Simultaneously, a vibrant folk art tradition flourished, with itinerant painters and craftsmen providing essential artistic services. Portraiture was in high demand as a means of preserving likeness and status.

James R. Hopkins, working in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, witnessed the impact of European modernism – Impressionism, Post-Impressionism (think Vincent van Gogh, Paul Cézanne), and Fauvism – but chose to apply his academic training, which included exposure to Whistler's tonalism, to American regional subjects. His career overlapped with the Ashcan School painters like Robert Henri and George Bellows, who focused on urban realism, and later, the American Scene painters.

Controversies and Complexities

The information provided also hints at controversies, though these seem to relate to a William H. Hopkins who was a judge, rather than the mathematician or any of the artists. This judge was described as sometimes acting "too casually" and potentially "neglecting court procedures," and was involved in a legal dispute over an "improper accusation" against a military officer. Such details highlight the importance of distinguishing between individuals who share a common name, as public records and historical accounts can easily lead to conflation if not carefully examined. For the artistic figures discussed, controversies are more typically related to artistic style or reception. Gerard Manley Hopkins's poetry, for example, was considered too unconventional for publication by many of his contemporaries, and his true recognition came much later. Artists often face criticism or misunderstanding, especially when their work challenges prevailing norms, as was the case with many Impressionists like Claude Monet or Post-Impressionists.

The Legacy of Hopkins in Art and Culture

The exploration of "William H. Hopkins, the painter" reveals a more complex and multifaceted story than a single artistic biography. It encompasses William H. Hopkins the scientist, whose interest in landscape painting connects him to the great artistic traditions of his time. It prominently features Gerard Manley Hopkins, the poet whose "word-paintings" and sketches demonstrate a profound visual acuity and connection to the art movements of his era. It includes Milton W. Hopkins, the American decorative and portrait painter, representing the vital role of artist-craftsmen in 19th-century society. And it touches upon James R. Hopkins, who documented a specific slice of American life with skill and empathy.

While a singular, dominant painter named William H. Hopkins matching all initially implied characteristics remains elusive, the collective contributions of these individuals named Hopkins enrich our understanding of art and culture in the 19th and early 20th centuries. They remind us that artistic expression takes many forms, from the scientific observation that informs an appreciation of landscape, to the poetic rendering of "inscape," to the practical application of paint on canvas or furniture. Each, in their own way, engaged with the visual world and left a mark, whether through scientific treatises, groundbreaking poetry, delicate sketches, or the painted chronicles of their communities. Their stories, intertwined and distinct, contribute to the vast and ever-evolving narrative of art history. The search for one often illuminates many, broadening our appreciation for the diverse ways creativity manifests.