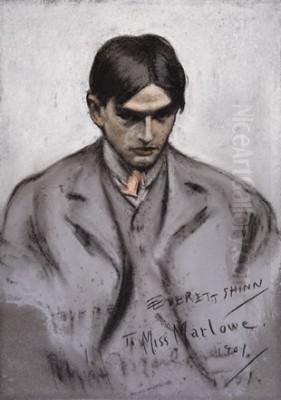

Everett Shinn (1876-1953) stands as a vibrant and multifaceted figure in the landscape of American art at the turn of the twentieth century. A key member of the Ashcan School and one of "The Eight," Shinn dedicated much of his career to capturing the pulsating energy, gritty realities, and dazzling spectacles of modern urban life, particularly in New York City. Unlike some of his contemporaries who focused primarily on the hardships of the working class, Shinn's gaze often shifted towards the artificial lights and dramatic flair of the theater, a world he not only depicted but actively participated in as a designer and playwright. His work, executed in oil, pastel, and various graphic media, offers a unique window into the dynamism and contrasts of his era.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born in Woodstown, New Jersey, a small Quaker community, Everett Shinn displayed artistic inclinations early on. His formal training began not in fine arts painting but in industrial design and engineering, which perhaps contributed to his later facility with stagecraft and decoration. However, his passion for drawing led him to Philadelphia, a burgeoning artistic center. There, he enrolled at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA), one of the nation's premier art institutions.

At PAFA, Shinn studied alongside other aspiring artists, but his most formative experiences arguably occurred outside the classroom. He took a job as a staff artist and illustrator for the Philadelphia Press newspaper. This role demanded rapid sketching skills and an eye for capturing the essence of current events and daily life. It was in the bustling environment of the newspaper office that he forged crucial relationships with fellow artist-reporters who would shape the future of American realism: George Luks, William Glackens, and John Sloan.

These young artists often gathered at the studio of Robert Henri, a charismatic painter and influential teacher who had returned from studying in Europe. Henri encouraged them to abandon academic conventions and the prevailing taste for genteel subjects. He urged them to look to the world around them – the streets, the tenements, the saloons, the theaters – for inspiration, and to paint life with honesty and vigor. This philosophy, nurtured in Philadelphia, would soon find its most potent expression in New York City.

The Move to New York and the Ashcan School

By the late 1890s, Shinn, along with Glackens, Luks, and Sloan, followed Robert Henri to New York City, drawn by its greater opportunities and its undeniable status as the epicenter of American modernity. Shinn quickly found work as an illustrator for prominent publications like The World, New York Herald, and Harper's Weekly. His ability to swiftly render dramatic scenes made him highly sought after. This journalistic work kept him immersed in the city's daily dramas, from fires and accidents to political rallies and society events, further honing his observational skills.

The group centered around Henri continued to meet, discuss art, and develop their shared artistic vision. They chafed under the conservative exhibition policies of the powerful National Academy of Design, which favored academic styles and often rejected works depicting contemporary urban realism. This frustration culminated in the landmark 1908 exhibition at the Macbeth Galleries in New York.

Organized by Henri, the show featured work by himself, Shinn, Sloan, Luks, Glackens, and three other artists working in different, though still modern, styles: Arthur B. Davies, Ernest Lawson, and Maurice Prendergast. Collectively, they became known as "The Eight." While stylistically diverse, they were united by their opposition to the Academy's stranglehold and their commitment to artistic independence. The exhibition was a succès de scandale, drawing large crowds and generating heated debate. Critics, sometimes derisively, labeled the urban realists within the group (Henri, Sloan, Luks, Glackens, and Shinn) the "Ashcan School" for their perceived focus on the grittier aspects of city life.

Shinn's Artistic Style: Urban Realism

Within the Ashcan School, Shinn carved out a distinct niche. While he shared his colleagues' interest in depicting the raw energy of New York, his approach often possessed a greater sense of drama and movement, perhaps influenced by his illustrative background. He was particularly adept at capturing the city under specific atmospheric conditions – snowstorms blanketing the streets, rain slicking the pavements, the artificial glow of streetlights at night.

His early New York scenes often focus on the bustling activity of streets and public squares. He depicted crowds navigating harsh weather, workers clearing snow, and the general tumult of urban existence. Unlike the more politically pointed work of John Sloan or the character studies of George Luks, Shinn's cityscapes often emphasize the overall visual spectacle and atmospheric effect. He frequently employed pastels, a medium he mastered, using quick, energetic strokes to convey immediacy and vibrancy. His use of color could be both descriptive and expressive, capturing the mood of a scene.

While associated with the "Ashcan" label, Shinn's subjects were not exclusively focused on the downtrodden. He also depicted scenes of middle-class leisure and the burgeoning consumer culture, capturing the dynamism of a city undergoing rapid transformation. His perspective often seems that of an engaged observer, fascinated by the visual richness and narrative potential of the modern metropolis.

European Influence and the Allure of the Theater

In 1900, Shinn traveled to Europe, spending time primarily in Paris and London. This trip proved pivotal. While already aware of European trends through Henri and publications, firsthand exposure deepened his understanding. He was particularly captivated by the work of French artists like Edgar Degas and Édouard Manet, who depicted modern Parisian life, including its cafes, boulevards, and, significantly, its theaters and ballets.

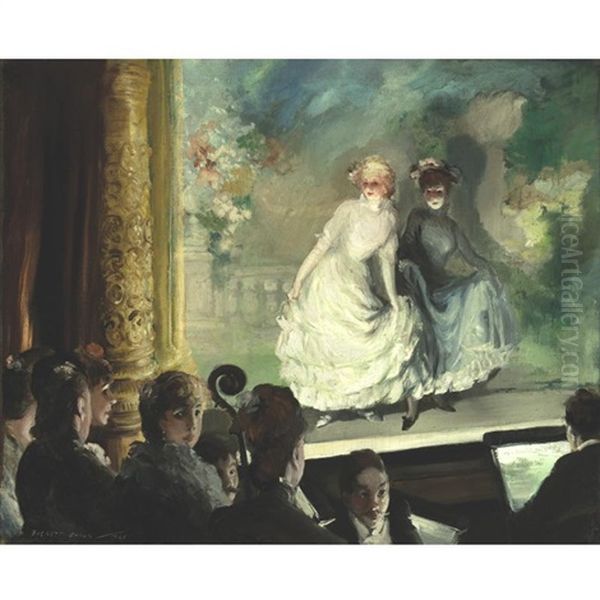

Degas's influence is especially palpable in Shinn's subsequent work. Like Degas, Shinn became fascinated by the world of performance – the dancers, actors, acrobats, and the audiences who watched them. He was drawn to the artificiality of stage lighting, the dramatic foreshortening created by unusual viewpoints (looking up from the orchestra pit or down from a box), and the dynamic interplay between performers and spectators. The theater offered a contained, heightened version of the urban drama he already found compelling.

Upon his return to New York, Shinn's focus increasingly shifted towards theatrical subjects. This wasn't merely an artistic interest; it reflected a deep personal passion. Shinn was enamored with the stage, eventually writing his own plays, designing sets, and even building small theaters within his own homes for amateur productions. This intimate involvement gave his depictions of theater an insider's perspective.

Masterpieces of the Stage

Shinn's paintings and pastels of theatrical scenes are among his most celebrated works. He captured the energy of vaudeville houses, the glamour of Broadway productions, and the specific atmosphere of venues like the London Hippodrome or Parisian music halls. Works like Dancer in White Before the Footlights (or variations like The White Ballet) showcase his Degas-inspired interest in dancers, capturing the figure bathed in the harsh, artificial glare of footlights, contrasting sharply with the shadowy background.

He often chose dramatic, oblique angles, placing the viewer in the midst of the experience – sometimes behind the scenes, sometimes among the audience, craning their necks for a better view. Stage Scene (c. 1906), depicting a performance possibly inspired by a Parisian music hall, is considered a quintessential example of his theatrical work. It masterfully contrasts the brightly lit stage figures with the silhouetted forms of the orchestra and the dimly perceived audience, creating a palpable sense of atmosphere and excitement.

Another notable work, London Hippodrome (1902), captures the vastness of the famous performance venue, focusing on the spectacle of the performance and the tiered ranks of the audience under the dramatic lighting. Shinn excelled at conveying the textures of costumes, the gestures of performers, and the charged relationship between the stage and the auditorium. His use of pastel allowed for both rapid execution, capturing fleeting moments, and rich, velvety textures appropriate for depicting stage costumes and dramatic lighting effects.

Beyond the Easel: Illustration and Design

Everett Shinn's artistic output extended far beyond easel painting. His roots in illustration remained a significant part of his career. He continued to produce illustrations for magazines and books throughout his life. His graphic work often displayed the same dynamism and keen observation found in his paintings. One notable commission was illustrating a version of Oscar Wilde's The Happy Prince, demonstrating his connection to literary and theatrical circles.

Shinn's fascination with the theater naturally led him into stage design. He designed sets for Broadway productions, including David Belasco's staging of The Easiest Way and the play The Parisian. His understanding of dramatic effect and visual composition served him well in creating immersive environments for the stage. His talents even extended to the nascent film industry; he is credited with design work for early films, such as Fire and Smoke.

Furthermore, Shinn became a sought-after decorative painter and muralist. He undertook significant commissions, including murals for the Stuyvesant Theatre (now the Belasco Theatre) in New York, built by the impresario David Belasco. His murals often featured elegant, sometimes Rococo-inspired themes, showcasing a different facet of his style compared to his gritty Ashcan scenes. He also painted murals for the Trenton City Council chambers in New Jersey, depicting scenes related to local industry and history.

His decorative work extended to private residences. He collaborated with the influential interior decorator Elsie de Wolfe, creating murals and decorative panels for her wealthy clients. A famous example of his decorative artistry is the elaborate painting he executed on a Steinway piano case for the playwright Clyde Fitch, a prominent figure in New York's literary and theatrical world. This diverse range of activities highlights Shinn's versatility and his ability to bridge the perceived gap between fine art, illustration, and decorative arts.

Personal Life and Artistic Circle

Shinn's personal life was as colorful and dramatic as some of his paintings. He married four times, with his first marriage being to Florence Scovell, who later became well-known in her own right as Florence Scovell Shinn, an artist, illustrator, and New Thought spiritual teacher and writer. They collaborated artistically in their early years together in New York. Subsequent marriages often ended tumultuously, contributing to an image of a somewhat volatile and theatrical personality.

He maintained close ties with his fellow members of "The Eight," particularly Robert Henri, John Sloan, William Glackens, and George Luks. Their camaraderie, forged in Philadelphia newspaper offices and Henri's studio, remained a significant factor in the development of American realism. Shinn was also connected to other prominent figures of the era, including the architect Stanford White, known for his Gilded Age designs and dramatic demise, and the aforementioned Clyde Fitch and Elsie de Wolfe.

Anecdotes suggest Shinn embraced theatricality in his own life. The story of him building numerous (perhaps miniature or model) theaters within his various residences speaks to his enduring obsession with the stage. His independent streak was also evident in his occasional refusal to participate in exhibitions he deemed unsuitable, asserting his artistic autonomy even when it might have been professionally disadvantageous. His life, like his art, seemed to oscillate between the gritty realities of making a living as an artist and the glamorous allure of performance and high society.

Later Career and Evolving Styles

As the 20th century progressed, artistic tastes shifted with the advent of European modernism, showcased dramatically in the Armory Show of 1913. While the Ashcan School's realism had been revolutionary in 1908, it soon looked less radical compared to Cubism and Fauvism. Some members of the group, like Sloan and Henri, continued to explore social realism, while others like Glackens moved towards a more Impressionist style influenced by Renoir.

Shinn's path in his later career was somewhat distinct. While he continued to paint scenes of New York life and the theater, his style sometimes leaned towards a more decorative, even flamboyant, aesthetic. Influences from 18th-century French Rococo painters like Jean-Honoré Fragonard and Antoine Watteau became apparent in some of his murals and decorative commissions. This embrace of elegance and historical styles set him apart from the ongoing trajectory of modernist abstraction.

This stylistic versatility, however, also led to criticism. Some art historians and critics felt that Shinn's later work lacked the raw power and social relevance of his earlier Ashcan paintings or the depth of his contemporaries like Sloan or George Bellows (a slightly younger artist associated with the Henri circle). His facility and willingness to undertake commercial illustration and decorative projects led some to view him as overly commercial or superficial compared to artists perceived as more purely dedicated to "fine art." He faced periods of financial difficulty and fluctuating critical reception during his lifetime.

Despite these criticisms, Shinn remained a productive artist, continuing to paint, illustrate, and undertake mural commissions well into the mid-century. He exhibited his work regularly, maintaining a presence in the New York art world even as dominant styles changed around him.

Legacy and Reassessment

Everett Shinn died in New York City in 1953. For a time, his reputation was somewhat overshadowed by other members of "The Eight," particularly Robert Henri, John Sloan, and George Bellows, whose works were often seen as more central to the narrative of American modernism and social realism. Shinn's stylistic diversity and his engagement with decorative arts and illustration perhaps made him harder to categorize and position within a straightforward art historical lineage.

However, in the later 20th and early 21st centuries, there has been a significant reassessment of Shinn's contributions. Art historians now recognize the unique value of his work in capturing specific facets of American urban experience at the turn of the century. His focus on the theater, in particular, is seen as a vital contribution, documenting a central aspect of popular culture and urban entertainment that other Ashcan artists explored less intensely.

His mastery of pastel is widely acknowledged, and his ability to convey movement, light, and atmosphere remains impressive. Furthermore, his career challenges traditional hierarchies between fine art, illustration, and design. Shinn moved fluidly between these realms, demonstrating that artistic skill and vision could be applied across different media and contexts. His work provides invaluable insight into the visual culture of New York during a period of immense social, cultural, and technological change.

Today, Everett Shinn's paintings, pastels, and illustrations are held in major American art museums, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Brooklyn Museum, and the Delaware Art Museum, among others. His work is studied for its artistic merit, its historical documentation, and its unique perspective on the intersection of everyday life and theatrical spectacle.

Conclusion

Everett Shinn was more than just an Ashcan painter; he was an artist deeply engaged with the multifaceted nature of modern American life. From the gritty snow-swept streets of New York to the dazzling footlights of the Broadway stage, his work captured the energy, contrasts, and spectacles of his time. His technical facility, particularly with pastel, allowed him to render scenes with immediacy and vibrancy. While his stylistic shifts and engagement with commercial and decorative arts sometimes complicated his critical reception, his legacy endures. As a chronicler of the city, a devotee of the theater, and a versatile artist comfortable in multiple disciplines, Everett Shinn holds a unique and important place in the history of American art. His work continues to offer a compelling glimpse into the dynamic world of early twentieth-century America.