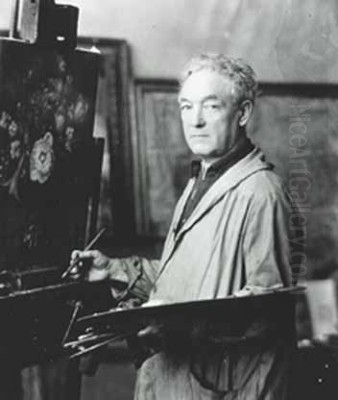

William James Glackens stands as a pivotal figure in the landscape of American art at the turn of the twentieth century. Born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on March 13, 1870, and passing away in Westport, Connecticut, on May 22, 1938, Glackens navigated the dynamic currents of artistic change, leaving behind a legacy that bridges American Realism and Impressionism. He was not only a gifted painter and illustrator but also a key organizer and participant in movements that challenged the academic norms of his time, most notably as a founder of the Ashcan School and a member of the influential group known as "The Eight." His work offers a vibrant window into the urban experience and leisure activities of Americans during a period of significant social and cultural transformation.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Philadelphia

Glackens' artistic journey began in his native Philadelphia, a city burgeoning with industrial growth and cultural activity. He received his formal art education at the prestigious Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA), where he studied under renowned instructors like Thomas Anshutz, who himself had been a student of the great realist Thomas Eakins. During his time at PAFA, and even earlier at Central High School, Glackens formed crucial friendships with fellow artists who would become lifelong colleagues and collaborators, including John Sloan.

Concurrent with his studies, Glackens embarked on a career as an artist-reporter and illustrator for various Philadelphia newspapers, including the Philadelphia Record and the Philadelphia Press. This demanding work required him to quickly observe and sketch scenes from life, honing his skills in capturing movement, character, and the essence of a moment. It was during this period that he worked alongside other talented illustrators who would also make their mark as painters: John Sloan, George Luks, and Everett Shinn. This group, often meeting to discuss art and life, formed the nucleus of what would later evolve into the Ashcan School.

A significant influence during these formative years was Robert Henri, an inspiring teacher and charismatic leader who returned to Philadelphia from studies in Paris in 1891. Introduced to Henri by Sloan, Glackens found in him a mentor who encouraged a direct, unvarnished approach to depicting contemporary life. Henri's studio became a hub for these young artists, fostering discussions about art, technique, and the need for a distinctly American form of expression, independent from the conservative constraints of institutions like the National Academy of Design (NAD).

The Ashcan School and The Rebellion of "The Eight"

The move from Philadelphia to New York City around 1896 marked a new chapter for Glackens and his circle. New York, with its teeming immigrant populations, bustling streets, and stark social contrasts, provided fertile ground for the brand of urban realism championed by Henri and his followers. This group, later dubbed the "Ashcan School" by critics (initially as a term of derision for their focus on gritty, everyday subjects), sought to portray the city's vitality without romanticization or academic prettiness. They focused on the unfiltered realities of urban existence – crowded tenements, smoky barrooms, lively parks, and the diverse inhabitants navigating the metropolis.

Glackens was a central figure in this movement. His early New York paintings often employed a darker palette, reminiscent of the tonalism of James McNeill Whistler or the realism of Édouard Manet, whom he admired. He captured street scenes and moments of public life with the keen eye developed during his years as an illustrator. However, even in these early works, a certain warmth and engagement with his subjects distinguished him from the more overtly critical or somber tones of some of his Ashcan colleagues.

The culmination of their shared dissatisfaction with the conservative exhibition policies of the National Academy of Design came in 1908. Led by Robert Henri, a group of eight painters organized an independent exhibition at the Macbeth Galleries in New York. This landmark show, featuring William Glackens, Robert Henri, John Sloan, George Luks, Everett Shinn, Arthur B. Davies, Ernest Lawson, and Maurice Prendergast, became known simply as "The Eight." While stylistically diverse – ranging from the urban realism of the core Philadelphia group to the more lyrical Impressionism of Lawson and the Post-Impressionist tapestries of Prendergast – they were united by their assertion of artistic independence and their focus on modern American subjects. The exhibition was a sensation, attracting significant public attention and critical debate, and marking a crucial step in the development of modern art in America.

Embracing Impressionism: The Influence of France

While deeply rooted in the American realist tradition fostered by Henri, Glackens' artistic trajectory took a decisive turn towards Impressionism, largely fueled by his experiences in Europe. He first traveled abroad in 1895, visiting Holland and settling in Paris for over a year with Robert Henri. This exposure to the works of the French Impressionists, particularly Edgar Degas and Édouard Manet, left a lasting impression. However, it was his subsequent trips to Europe, and particularly his growing admiration for Pierre-Auguste Renoir, that profoundly reshaped his style.

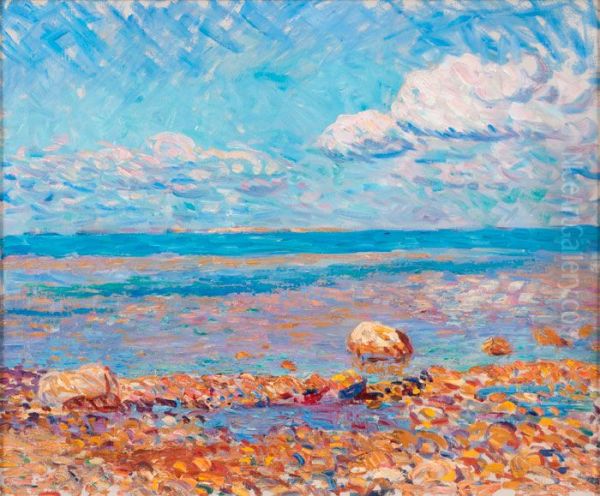

Glackens developed a deep affinity for Renoir's vibrant color, sensuous brushwork, and joyful depictions of leisure and domesticity. Over time, his own palette brightened considerably, moving away from the darker tones of his early Ashcan works. He adopted lighter, feathery brushstrokes and became increasingly preoccupied with capturing the effects of sunlight and atmosphere. This shift is evident in works created after the turn of the century, particularly those depicting scenes from his travels or summer holidays.

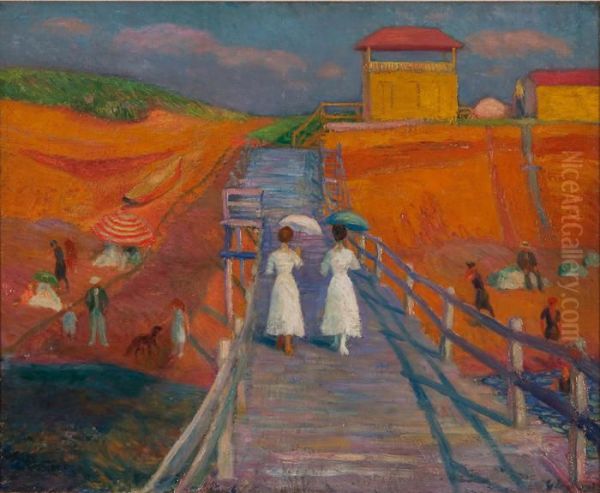

Paintings like Luxembourg Gardens (c. 1896), created during an early trip, already show an interest in Parisian park life, a theme favored by the Impressionists. Later works, such as Cape Cod Pier (1908) and Wickford Low Tide (1909), showcase his evolving style with their sun-drenched landscapes, sparkling water, and lively application of paint. He became known for his depictions of beaches, parks, and outdoor cafes, capturing the relaxed pleasures of middle-class life with an optimistic spirit that contrasted with the grittier subjects often associated with the Ashcan School. This embrace of a lighter, more decorative style led some critics, then and later, to label him the "American Renoir," a comparison that acknowledged his stylistic debt but sometimes overshadowed his unique contributions.

Mature Style: Capturing the Vibrancy of Modern Life

In his mature phase, Glackens synthesized his realist foundations with his passion for Impressionist color and light. He remained a keen observer of the world around him, but his focus shifted towards the more comfortable aspects of modern urban and suburban life. His canvases often depict bustling city squares, shoppers navigating crowded sidewalks, families enjoying seaside holidays, and intimate moments within sunlit interiors. He excelled at capturing the energy and dynamism of New York City, as seen in the celebrated Madison Square Christmas Shoppers (1912), where flickering lights, swirling crowds, and snowy atmosphere are rendered with vibrant strokes and a keen sense of place.

Unlike some of his Ashcan peers who maintained a focus on social commentary, Glackens seemed more drawn to the visual delights and pleasant social interactions of his environment. His works often feature women and children, rendered with affection and an eye for fashion and gesture. Portraits of his wife, the artist Edith Dimock Glackens, and their children, Ira and Lenna, appear frequently, offering glimpses into their family life. Works like Artist’s Daughter in Chinese Costume (1918) and Breakfast Porch (1925) exemplify this focus on domestic intimacy and decorative arrangement.

His subject matter also extended to still lifes and floral arrangements, allowing him to explore pure color and form, further aligning him with Impressionist and Post-Impressionist sensibilities. Throughout his career, Glackens maintained a strong sense of structure and drawing beneath the shimmering surfaces of his paintings, a testament to his academic training and his background as an illustrator. He possessed a remarkable ability to organize complex scenes and render figures with solidity, even amidst the play of light and broken color.

The Enduring Illustrator

Although painting became his primary focus, Glackens continued to work as an illustrator for major publications like Collier's Weekly, The Saturday Evening Post, and McClure's Magazine well into the early twentieth century. This work provided financial stability but also continued to inform his artistic practice. His illustrations, often depicting scenes of contemporary social life, adventure, and romance, shared the same vitality and observational acuity found in his paintings.

His experience in meeting deadlines and conveying narrative through images undoubtedly contributed to the sense of immediacy and dynamism in his painted work. He understood how to capture gesture, expression, and atmosphere efficiently and effectively. Furthermore, his illustrations often showcased his mastery of composition and his developing interest in color and light, even within the constraints of print media. While some critics occasionally dismissed illustration as lesser than fine art, for Glackens, it was an integral part of his artistic identity, sharpening the skills he brought to his canvases. His background perhaps contributed to the criticism mentioned by his son, Ira Glackens, that some found his focus less on harsh social realities and more on the pleasant aspects of life, a potential byproduct of illustrating for popular magazines.

Advisor to Albert C. Barnes: Shaping a Landmark Collection

Beyond his own artistic production, Glackens played a crucial, if sometimes overlooked, role in shaping one of America's most important collections of modern art. In 1912, his former high school classmate, the eccentric millionaire Dr. Albert C. Barnes, who had made his fortune in pharmaceuticals, decided to seriously pursue art collecting. Knowing Glackens' discerning eye and his familiarity with the European art scene, Barnes entrusted him with a significant sum ($20,000) and sent him to Paris on a buying trip.

This mission proved transformative for the future Barnes Foundation. Glackens returned with works by Renoir, Manet, Degas, Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, and others, laying the groundwork for what would become a world-renowned collection heavily focused on French Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, and early Modernism. Glackens' selections, particularly his enthusiasm for Renoir and Paul Cézanne, deeply influenced Barnes' own taste. He introduced Barnes to key figures in the Paris art world, including dealers like Paul Durand-Ruel and Ambroise Vollard, and artists like Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso, whose works would become cornerstones of the collection alongside masterpieces by Vincent van Gogh and Georges Seurat.

Glackens' role as Barnes' initial art advisor was instrumental not only in launching the collection but also in bringing significant examples of European modernism to the United States, contributing to a broader appreciation and understanding of these movements among American artists and audiences. This act of connoisseurship highlights Glackens' deep understanding of European art and his position as a vital link between the art worlds of Paris and America.

Controversies, Anecdotes, and Artistic Evolution

Like many artists challenging the status quo, Glackens' career was not without its points of discussion and even controversy. His stylistic shift towards Renoir, while resulting in many beautiful and beloved paintings, led to persistent criticism that he had become too derivative, sacrificing his own unique voice. This debate about influence versus imitation followed him, particularly in his later career during the 1920s and 30s, when American art was increasingly exploring native subjects and modernist idioms distinct from European models.

His association with "The Eight" placed him firmly within the progressive camp of American art, yet his subject matter often seemed gentler and less overtly critical than that of Sloan or Luks. While they might depict the struggles of the working class or the seedier side of urban life, Glackens often focused on the leisure activities of the middle and upper classes, leading some to perceive his realism as less socially engaged.

An intriguing, though perhaps apocryphal, anecdote related by his son, Ira Glackens, concerns the infamous 1917 exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists, where Marcel Duchamp anonymously submitted his readymade sculpture, Fountain (a urinal). According to Ira, his father, who was involved in the society, was part of the discussion about the controversial submission and allegedly suggested that the offending object simply be hidden or disposed of to avoid further conflict. While the exact details remain debated, the story places Glackens at the periphery of a key moment in Dadaist provocation.

Ultimately, Glackens' career reflects a continuous evolution. He absorbed lessons from his training, his work as an illustrator, his association with the Ashcan realists, and his deep engagement with French Impressionism. He forged a personal style that celebrated light, color, and the vibrant spectacle of modern life, even if it sometimes drew criticism for its optimism or its stylistic allegiances.

Legacy and Place in American Art History

William Glackens occupies a significant and somewhat unique position in American art history. He was undeniably a founder and key member of the Ashcan School, contributing to its mission of depicting contemporary urban reality with honesty and vigor. His early works stand as important examples of American realism at the turn of the century. Simultaneously, he became one of the foremost American practitioners of Impressionism, adapting its techniques and spirit to American subjects with remarkable skill and sensitivity.

He played an active role in the key events that shaped American modernism, from the rebellion of "The Eight" to his participation in organizing the groundbreaking Armory Show of 1913 through the Association of American Painters and Sculptors (AAPS), alongside artists like Walt Kuhn and Walter Pach. This exhibition famously introduced European avant-garde art, including works by Duchamp, Matisse, and Constantin Brancusi, to a wider American audience, sparking outrage and revolutionizing the course of art in the United States.

His influence extended beyond his own canvases through his critical role in advising Albert C. Barnes, helping to build a collection that remains a vital resource for the study of modern art. His work continues to be celebrated for its technical proficiency, its joyful embrace of color and light, and its evocative portrayal of American life during a period of profound change. While debates about his relationship to Renoir or the social depth of his subjects may persist, his status as a major figure who successfully navigated the transition from realism to a distinctly American form of Impressionism is secure. William Glackens remains a beloved chronicler of the American scene, whose vibrant paintings continue to engage and delight viewers.