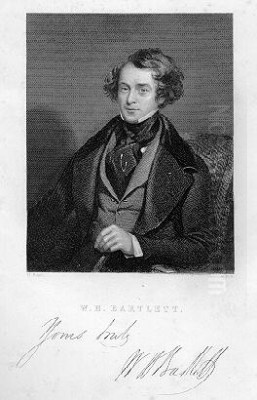

William Henry Bartlett stands as a significant figure in the landscape of 19th-century British art. Born in London in 1809, he rose from a middle-class background to become one of the most prolific and widely recognized topographical artists and illustrators of his era. His career coincided with a burgeoning public appetite for illustrated travel books, fueled by advancements in printing technology, particularly steel engraving. Bartlett's meticulous drawings, translated into fine engravings, offered audiences captivating glimpses of landscapes and landmarks across Britain, Europe, the Middle East, and North America, shaping perceptions and documenting a world undergoing rapid change. His work, while often intended for mass consumption, possesses an enduring artistic merit and significant historical value.

Early Life and Formative Training

William Henry Bartlett was born in Kentish Town, London, into a moderately prosperous family. His formal education occurred at a private school until around 1821 or 1822, when, at the young age of twelve or thirteen, his artistic inclinations led him to an apprenticeship that would prove pivotal. He became a pupil of John Britton (1771-1857), a noted architect, antiquarian, writer, and publisher, renowned for his illustrated works on British architectural heritage.

Under Britton's tutelage, Bartlett received rigorous training in architectural draughtsmanship and the study of antiquities. His initial tasks involved creating precise drawings of buildings and ruins, contributing to Britton's ambitious publications. An early example of his work can be seen in Britton's The History and Antiquities of the Cathedral Church of... series and later in Chronological History and Graphic Illustrations of Christian Architecture in England (1826). This foundation provided him with an exceptional eye for detail and structure, qualities that would remain hallmarks of his later landscape work.

During his apprenticeship, Bartlett was not confined solely to Britton's direct influence. He was exposed to the broader artistic currents of the time, absorbing the styles of established watercolourists and topographical artists. The work of Samuel Prout (1783-1852), known for his picturesque depictions of continental European architecture and street scenes, and John Sell Cotman (1782-1842), a leading figure of the Norwich School famed for his bold compositions and watercolour technique, likely informed Bartlett's developing aesthetic sensibilities. This period laid the essential groundwork for his transition from purely architectural illustration to the broader field of landscape art.

The Emergence of a Landscape Illustrator

While Bartlett's initial training focused heavily on architectural accuracy, his innate interest in the wider landscape soon became apparent. His sketches began to incorporate more extensive scenic elements, moving beyond the strict confines of architectural studies. John Britton recognized this evolving talent and shift in focus. This led to a significant commission that marked a turning point in Bartlett's career: the creation of illustrations for Britton's Picturesque Antiquities of English Cities (1830, though some sources date publication later, around 1836).

This project allowed Bartlett to combine his skill in rendering architectural detail with a growing sensitivity to atmosphere, light, and natural surroundings. The success of these illustrations helped establish his reputation as a capable and appealing topographical artist. It demonstrated his ability to create views that were not only informative but also aesthetically pleasing, capturing the romantic appeal of Britain's historic towns and cities.

His burgeoning reputation attracted the attention of publishers seeking skilled artists for the rapidly expanding market of illustrated books. The early 1830s saw him increasingly employed to provide drawings for various publications, often involving travel within the British Isles to sketch specific locations. This period solidified his professional identity as an artist specializing in landscape and topographical views, setting the stage for the international scope his work would later achieve.

Steel Engraving and the Power of Publication

A crucial factor in William Henry Bartlett's widespread success was the technology of steel engraving. Perfected in the 1820s, steel engraving allowed for much harder printing plates compared to traditional copper, enabling significantly larger print runs before the plate wore out. This meant that intricate, detailed images could be reproduced in the thousands, making illustrated books more affordable and accessible to a growing middle-class readership. Bartlett's detailed, precise drawing style was perfectly suited to this medium.

Bartlett typically worked in watercolour or sepia wash on location, creating detailed sketches filled with information about topography, architecture, and often, human activity. These original drawings were then handed over to skilled engravers who meticulously translated the image onto the steel plate. Bartlett collaborated with many of the finest engravers of the day, including figures like Robert Wallis (1794-1878), James Tibbits Willmore (1800-1863), John Cousen (1804-1880), Edward Finden (1791-1857), William Finden (1787-1852), and Charles Mottram (1807-1876). Their expertise was essential in capturing the nuances of Bartlett's originals in the final printed form.

The publisher George Virtue (1794–1868) played a particularly important role in Bartlett's career. Virtue specialized in producing high-quality illustrated books, often issued in serial parts to make them more affordable. He recognized Bartlett's talent and reliability and commissioned him for numerous extensive projects, including his most famous works on Switzerland, the Middle East, America, and Canada. This partnership proved immensely fruitful, disseminating Bartlett's views across the English-speaking world and cementing his status as a leading illustrator.

A Prolific Traveller: Documenting the World

Bartlett was an exceptionally industrious and adventurous traveller, especially considering the rigors of international journeys in the first half of the 19th century. His quest for fresh subjects took him far beyond the British Isles. His itineraries were demanding, requiring long sea voyages, arduous overland treks, and the ability to work efficiently under often challenging conditions. He possessed a remarkable capacity for producing a high volume of detailed sketches during these expeditions.

His European travels included multiple visits to Switzerland, resulting in the illustrations for Switzerland Illustrated (text by William Beattie, published 1836). He also journeyed through the Netherlands, Belgium, the Rhine Valley, and the Balkan Peninsula. His travels extended to the Mediterranean and the Middle East, including Constantinople (Istanbul), Asia Minor, Syria, Palestine, and Egypt. These journeys provided the material for popular illustrated works like The Bosphorus, The Danube, and Walks about the City and Environs of Jerusalem (published 1844).

Perhaps most significantly for his international reputation, Bartlett undertook four separate voyages to North America. These occurred roughly in 1836-1837, 1838, 1841, and 1852. During these trips, he travelled extensively through the eastern United States and Canada, sketching landscapes, burgeoning cities, and natural wonders. These expeditions formed the basis for his most celebrated publications, American Scenery and Canadian Scenery Illustrated. His dedication to firsthand observation ensured a level of authenticity highly valued by his audience.

Landmark Publications: American and Canadian Scenery

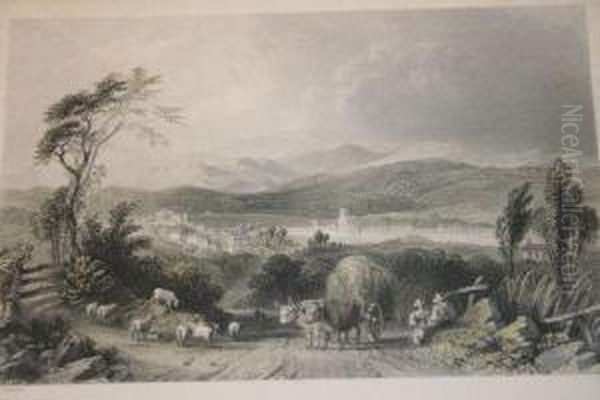

Among Bartlett's most enduring legacies are the illustrated volumes American Scenery; or, Land, Lake, and River Illustrations of Transatlantic Nature (1840) and Canadian Scenery Illustrated (1842). Both were published by George Virtue, featuring Bartlett's engravings accompanied by text written by the popular American author Nathaniel Parker Willis (1806-1867). These works were immensely popular on both sides of the Atlantic, offering many Britons their first comprehensive visual introduction to the landscapes of the United States and Canada.

American Scenery primarily focused on the northeastern United States, featuring views of the Hudson River Valley, Niagara Falls, New England towns, and major cities like New York, Boston, and Washington D.C. Bartlett captured iconic natural landmarks like the Natural Bridge in Virginia and burgeoning urban and industrial scenes, such as the Erie Canal at Lockport. His views often included elements of daily life, adding human interest and context to the landscapes.

Canadian Scenery Illustrated similarly covered eastern Canada, showcasing the dramatic landscapes of the St. Lawrence River, Quebec City, Montreal, the Ottawa River, and, again, the spectacle of Niagara Falls (from the Canadian side, including the famous Horseshoe Falls). Bartlett's illustrations presented Canada as a land of vast forests, powerful rivers, and picturesque settlements, blending wildness with emerging civilization.

These publications were significant not only for their artistic merit but also for their cultural impact. They helped shape perceptions of North America, presenting it as a land of both sublime natural beauty and dynamic progress. While sometimes romanticized, Bartlett's views provided invaluable documentation of the continent during a period of significant development. His work can be seen in dialogue with, though distinct from, the oil paintings of the emerging Hudson River School artists like Thomas Cole (1801-1848) and Asher B. Durand (1796-1886), who were simultaneously forging a distinctly American landscape tradition.

Depicting the East and Europe

Bartlett's artistic endeavors were not limited to North America. His travels in the Near East yielded a rich portfolio of sketches that were published in works like Walks about the City and Environs of Jerusalem (1844) and Forty Days in the Desert (1848). His depictions of the Holy Land were particularly popular, catering to the intense contemporary interest in biblical history and geography. He rendered sacred sites, ancient ruins, and desert landscapes with his characteristic attention to detail, often incorporating figures in local dress to enhance the sense of place. His work in this region invites comparison with other British artists who travelled to the East, such as the celebrated David Roberts (1796-1864), though Bartlett's focus remained primarily on topographical illustration for publication rather than large-scale exhibition paintings.

His European views, particularly those for Switzerland Illustrated (1836), captured the dramatic Alpine scenery that fascinated the Romantic imagination. He depicted towering peaks, glaciers, lakes, and picturesque villages, contributing to the popular image of Switzerland as a land of sublime natural beauty. These works stand alongside the Alpine scenes of his great contemporary J.M.W. Turner (1775-1851), although Bartlett's approach was generally more focused on clear representation than Turner's atmospheric and often abstract interpretations. His depictions of continental towns and cities also echoed the picturesque tradition exemplified by Samuel Prout. Bartlett's ability to adapt his style to different geographical locations while maintaining his core commitment to detailed observation was a key element of his success.

Artistic Style: Precision, Picturesque, and Sublime

William Henry Bartlett's artistic style is characterized by its clarity, precision, and strong compositional sense. Working primarily for engravers, he developed a technique that translated well into linear reproduction. His drawings are typically detailed and informative, clearly delineating topographical features, architectural elements, and often, human figures that add scale and narrative interest. He had a fine sense of light and shadow, using tonal contrasts to create depth and drama within his compositions.

His work often embodies the aesthetic ideals of the Picturesque, popular in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. This involved seeking out views that offered variety, irregularity, interesting textures, and a harmonious blend of nature and human elements, such as rustic cottages or ruined castles. Many of his European and British scenes fit comfortably within this mode, presenting charming and engaging vignettes. His training under Britton, an antiquarian, likely fostered his appreciation for the visual appeal of historic structures, a common theme in Picturesque art, also seen in the work of architectural specialists like Augustus Pugin (1812-1852).

However, Bartlett was equally adept at capturing the Sublime – experiences of awe, grandeur, and even terror inspired by the overwhelming power of nature. His depictions of Niagara Falls, vast mountain ranges in Switzerland, or expansive desert landscapes in the Middle East evoke this sense of nature's immensity. While perhaps lacking the visionary intensity of J.M.W. Turner or the profound spiritual connection to nature found in John Constable (1776-1837) or Samuel Palmer (1805-1881), Bartlett effectively conveyed the scale and drama of these scenes to his audience through careful composition and emphasis on defining features. His style was less about personal expression and more about skilled, accessible representation, making him distinct from, yet contemporary to, marine and landscape painters like Clarkson Stanfield (1793-1867).

Later Years and Enduring Legacy

Bartlett maintained a demanding schedule of travel and production throughout his career. His final journey took him back to the Near East in 1853-1854. Tragically, while returning from this expedition aboard a French steamer near Malta, he succumbed to a sudden illness and died in September 1854, at the relatively young age of 45. His premature death cut short a remarkably productive career.

Despite his popular success, there is some indication that Bartlett may have faced financial difficulties towards the end of his life. His extensive collection of sketches and watercolour drawings was auctioned off by Christie & Manson in London in 1855. While his steel engravings reached a vast audience, original works by Bartlett, particularly finished watercolours, are less common. Intriguingly, no oil paintings by his hand are known to have survived, suggesting he remained focused on graphic media intended for reproduction.

William Henry Bartlett's legacy lies primarily in his vast output of topographical illustrations. He was one of the foremost practitioners of this genre during its mid-19th-century heyday. His works provided invaluable visual documentation of diverse parts of the world at a time before photography became widespread. They informed and shaped the British public's understanding of foreign lands and even their own country's heritage. His detailed and attractive views were praised by contemporaries like N.P. Willis for their ability to convey "the vivid impression of reality."

Today, Bartlett's prints remain highly collectible. His original drawings and watercolours are held in major museum collections, including the Victoria and Albert Museum and the British Museum in London, and the National Gallery of Canada, attesting to their artistic and historical significance. He stands as a key figure in the history of illustration and popular publishing, an artist whose meticulous craft opened windows onto the wider world for a fascinated 19th-century audience.

Conclusion

William Henry Bartlett was more than just a skilled draughtsman; he was an intrepid traveller and a crucial visual chronicler of his time. His career perfectly intersected with the rise of steel engraving and the public's desire for illustrated knowledge of the world. Through his partnership with publishers like George Virtue and engravers like Mottram, Wallis, and Willmore, his detailed and picturesque views reached an unprecedented audience. From the historic cities of Britain to the sublime landscapes of Switzerland, the deserts of the Near East, and the burgeoning continent of North America, Bartlett captured the world with remarkable diligence and artistry. While operating within the conventions of topographical illustration, his work possesses a clarity, charm, and documentary value that ensures its continued relevance and appreciation in the annals of art history.