William Henry Pyne (1769/70–1843) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the landscape of British art and letters during the late Georgian and Regency periods. A man of diverse talents, Pyne was not only a painter and illustrator of considerable skill, particularly in watercolour, but also a prolific writer, an astute art critic, an innovative publisher, and a keen observer of the social fabric of his time. His works provide an invaluable visual and textual record of British life, from the grandeur of royal palaces to the everyday activities of its populace. This exploration delves into the life, career, artistic style, major publications, collaborations, and enduring legacy of this industrious artist and author.

Early Life and Artistic Inclinations

Born in London around 1769 or 1770, William Henry Pyne was the son of John Pyne, a leather seller or fellmonger, and Mary Craze. His upbringing in the bustling capital undoubtedly exposed him to a wide array of sights and social interactions that would later inform his artistic and literary output. From an early age, Pyne exhibited a natural aptitude for drawing, a talent that his family, despite their trade background, appears to have supported.

His formal artistic education began under the tutelage of Henry Pars, a respected drawing master who ran a well-known drawing school in the Strand. Pars's academy was a preparatory institution for many aspiring artists, providing foundational skills in draughtsmanship. Following this, in 1784, Pyne was apprenticed to the engraver William Sharp. Sharp was a prominent figure in the engraving world, known for his reproductive engravings after famous paintings. This apprenticeship would have provided Pyne with a thorough grounding in printmaking techniques, although he would later become more renowned for his watercolours and aquatints than for line engraving.

Despite this training, Pyne's primary passion lay in painting, particularly in watercolour. He was largely self-taught in this medium, developing his skills through diligent practice and observation. He began to exhibit his work publicly at a young age, with his first appearance at the Royal Academy of Arts in 1790, where he showed landscape and rustic figure subjects. He would continue to exhibit there sporadically until 1811.

The Emerging Artist and Writer

In the early stages of his career, Pyne focused on producing picturesque landscapes and genre scenes, often featuring rural figures and cottages. These works were characteristic of the prevailing taste for the "picturesque," a concept popularized by writers like William Gilpin, which valued irregularity, rustic charm, and a certain romantic wildness in landscape and architecture. Pyne's early watercolours demonstrate a delicate touch and a keen eye for detail, capturing the nuances of the English countryside and its inhabitants.

However, Pyne's ambitions extended beyond simply painting. He possessed a literary bent and a sharp intellect, which led him to explore writing and art criticism. This dual path as an artist-writer would become a defining characteristic of his career. He recognized the growing market for illustrated books and periodicals, and he astutely positioned himself to contribute to this burgeoning field.

A significant development in the British art world during this period was the rise of watercolour painting as a respected medium in its own right. Pyne was at the forefront of this movement. In 1804, he was one of the founding members of the Society of Painters in Water Colours (often referred to as the Old Watercolour Society). This society was established to provide a dedicated exhibition space for watercolour artists, who often felt overshadowed by oil painters at the Royal Academy. Pyne exhibited with the society in its inaugural year. However, his association was short-lived; he resigned in 1805, reportedly due to dissatisfaction with the society's increasingly exclusive policies or perhaps due to his own independent and sometimes restless nature.

Landmark Publications and Collaborations

William Henry Pyne's most enduring contributions arguably lie in the realm of illustrated books, where his skills as an artist, writer, and sometimes publisher converged. He was involved in several ambitious projects that have become invaluable historical and artistic documents.

Microcosm of London

One of his most celebrated collaborations was with the publisher Rudolph Ackermann on Microcosm of London; or, London in Miniature. Published in parts between 1808 and 1810 and then as a three-volume set, this monumental work featured 104 hand-coloured aquatint plates. The architectural elements in the plates were drawn by Augustus Charles Pugin, a French-born architect and draughtsman renowned for his precise architectural renderings. The figures populating these scenes were initially intended to be by Thomas Rowlandson, a celebrated caricaturist and watercolourist. However, Rowlandson's often boisterous and satirical style was perhaps deemed not entirely suitable for the overall tone Ackermann and Pyne envisioned for certain scenes. Consequently, Pyne himself took on the task of drawing many of the figures, demonstrating his versatility and his ability to capture the diverse characters of London life with a more descriptive, less caricatured approach.

The Microcosm aimed to provide a comprehensive visual survey of London's public buildings, institutions, and notable interiors, from churches and theatres to markets and prisons. Pyne also contributed much of the accompanying text, which offered historical and descriptive accounts of the locations depicted. The book was a triumph of the aquatint process, a printmaking technique that allowed for subtle tonal gradations, mimicking the effect of watercolour washes, and was perfectly suited for hand-colouring. The plates are prized for their vibrancy, detail, and the lively human element that Pyne and his collaborators brought to them. It remains a primary source for understanding the architecture and social life of Regency London. Other artists whose work often appeared in Ackermann's publications, and who were part of this vibrant print culture, included George Moutard Woodward and, in later periods, the Cruikshank brothers, George and Robert.

The History of the Royal Residences

Perhaps Pyne's most ambitious solo project as an author and overall director was The History of the Royal Residences of Windsor Castle, St. James's Palace, Carlton House, Kensington Palace, Hampton Court, Buckingham House, and Frogmore. Published in three lavish volumes between 1816 and 1819, this work contained 100 hand-coloured aquatint plates. While Pyne wrote the extensive historical and descriptive text, the plates were based on drawings by several accomplished artists, including Charles Wild, James Stephanoff, Richard Cattermole, George Samuel, and William Westall. These drawings were then engraved in aquatint by skilled printmakers such as Thomas Sutherland, Daniel Havell, Richard Reeve, and W. J. Bennett.

Pyne's text provided detailed accounts of the history, architecture, and interior decoration of these royal abodes, including descriptions of their furnishings and art collections. The plates are remarkable for their meticulous depiction of opulent interiors, capturing the grandeur and specific character of each residence. The History of the Royal Residences is an invaluable record of royal taste and the state of these palaces in the early 19th century, particularly Carlton House, which was demolished shortly thereafter. The production was a significant undertaking, reflecting Pyne's organizational skills and his deep knowledge of art and architectural history. The quality of the aquatints, with their rich colours and fine detail, set a high standard for such publications.

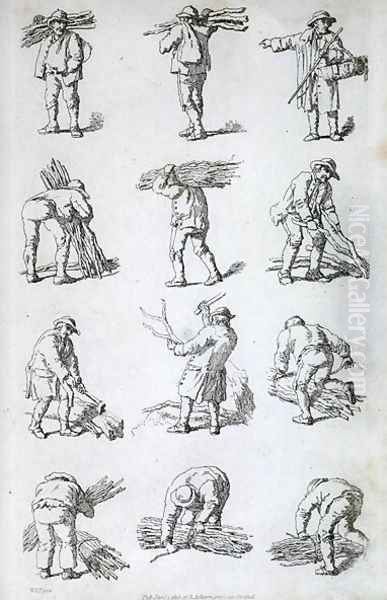

Costume of Great Britain

Earlier in his career, Pyne had also produced The Costume of Great Britain, published by William Miller in 1804 (though some sources date it to 1802 or 1808 for its first edition). This work featured 60 hand-coloured aquatint plates designed and engraved by Pyne himself. Unlike many costume books that focused on aristocratic or historical dress, Pyne's Costume of Great Britain offered a broader survey, depicting the attire of various trades, professions, and social ranks, from milkmaids and miners to lawyers and academics. The accompanying text, also by Pyne, provided descriptions of these occupations and social types. This book is a significant contribution to social history, offering a visual panorama of British society at the turn of the 19th century. It showcases Pyne's keen observational skills and his interest in the everyday lives of ordinary people.

Other Works and Writings

Pyne was a prolific writer beyond these major illustrated books. He contributed articles and art criticism to various periodicals, often under the pseudonym "Ephraim Hardcastle." One of his notable series of articles, "The Rise and Progress of Water-Colour Painting in England," was published in the Somerset House Gazette, a periodical he himself edited between 1823 and 1824. These writings are important for their contemporary insights into the development of the British watercolour school, and he played a role in championing artists like Thomas Girtin and J.M.W. Turner, recognizing their pivotal contributions.

He also authored Wine and Walnuts; or, After Dinner Chit-Chat (1823), a collection of anecdotes and reminiscences about artists and literary figures of his time, offering a lively, if sometimes gossipy, glimpse into the cultural milieu of Regency London. Other publications included Etchings of Rustic Figures for the Embellishment of Landscape (1815) and Lancashire Illustrated (1829), further demonstrating his versatility. His son, George Pyne (1800/01–1884), also became an artist, specializing in architectural watercolours, clearly influenced by his father's interests.

Artistic Style and Thematic Focus

William Henry Pyne's artistic style is characterized by its clarity, meticulous detail, and often, a gentle, picturesque charm. As a watercolourist, he favored clear washes and precise draughtsmanship. His figures, while not always anatomically perfect, are lively and expressive, effectively conveying character and activity. He had a particular talent for composing group scenes and integrating figures naturally into their architectural or landscape settings.

His work in aquatint, especially when hand-coloured, achieved a richness and luminosity that rivaled original watercolours. He understood the capabilities of the medium and how to exploit it for maximum effect, whether depicting the intricate details of a Gothic interior or the bustling activity of a London street.

Thematically, Pyne's work covered a broad spectrum. He was drawn to:

Architectural Subjects: As seen in Microcosm and Royal Residences, he had a deep appreciation for architecture, both grand and vernacular.

Social Observation: Costume of Great Britain and many of his individual prints and drawings reveal a fascination with the diverse occupations and social strata of British society. He depicted laborers, street vendors, professionals, and gentry with an observant and often sympathetic eye.

Picturesque Landscapes and Rural Life: His earlier works, and many of his etchings, focused on rustic scenes, cottages, and rural figures, aligning with the picturesque aesthetic.

Historical Documentation: Pyne clearly understood the value of art as a historical record, and many of his projects were conceived with the aim of preserving a visual account of contemporary life, architecture, and customs.

His style can be contrasted with some of his more flamboyant contemporaries. While Thomas Rowlandson, for example, was known for his dynamic, often satirical and exaggerated figures, Pyne's approach was generally more descriptive and illustrative, aiming for a faithful representation infused with picturesque appeal. He shared with artists like Paul Sandby, an early pioneer of aquatint and watercolour landscapes, an interest in topographical accuracy combined with artistic sensibility.

Challenges and Later Life

Despite his considerable talents and prolific output, William Henry Pyne's life was not without its financial struggles. The production of large-scale illustrated books was a costly and speculative business. While some of his projects were successful, others may have incurred debts. Like many artists and writers of the period, he seems to have lived a somewhat precarious existence.

Records indicate that he faced periods of financial hardship, and he was imprisoned for debt on at least two occasions, in 1828 and again in the 1830s (possibly 1835 in the King's Bench Prison). These difficulties, however, did not entirely curtail his activities. He continued to write and publish, demonstrating remarkable resilience. His later years were spent in relative obscurity, and he died in poverty in Paddington, London, on May 29, 1843.

His son, George Pyne, continued the family's artistic tradition, achieving recognition for his own architectural watercolours, some of which were exhibited at the Royal Academy and other institutions. George's style, while distinct, owed a debt to his father's meticulous approach to architectural subjects.

Legacy and Historical Significance

William Henry Pyne's legacy is multifaceted. As an artist, he was a skilled watercolourist and a master of the hand-coloured aquatint, contributing significantly to the "golden age" of English book illustration. His works are prized by collectors and institutions for their artistic merit and historical value. Artists like David Cox and Peter De Wint, who became leading figures in the watercolour movement, were his contemporaries and part of the evolving landscape of British art that Pyne documented and participated in.

As a writer and art critic, he provided valuable contemporary commentary on the art world of his time, particularly on the development of watercolour painting. His writings, especially those under the "Ephraim Hardcastle" persona, offer insights into the personalities, practices, and debates that shaped British art in the early 19th century. His championing of artists like Girtin and Turner in his historical accounts of watercolour painting helped to solidify their reputations.

His publications, particularly Microcosm of London and The History of the Royal Residences, remain indispensable resources for historians of art, architecture, and social customs. They offer a vivid and detailed window into Regency England, capturing the appearance of its buildings, the dress of its people, and the activities of its daily life with a richness that few other contemporary sources can match. The collaborative nature of these projects also highlights the interconnectedness of the London art world, involving a network of artists, engravers like Joseph Constantine Stadler (who also worked for Ackermann), and publishers.

While he may not have achieved the same level of individual fame as some of his contemporaries like J.M.W. Turner or John Constable, William Henry Pyne's collective body of work represents a monumental achievement. He was an industrious and versatile figure whose keen eye and diligent hand recorded a pivotal era in British history with enduring artistry and insight. His dedication to documenting the world around him, from the humblest worker to the most splendid royal apartment, ensures his lasting importance as a chronicler of his age. His influence can also be seen in the continued tradition of topographical and architectural illustration that flourished throughout the 19th century, with artists like Samuel Prout and Thomas Shotter Boys further developing the depiction of urban and architectural scenes. Pyne, through his diverse contributions, remains a key figure for understanding the visual culture of early 19th-century Britain.