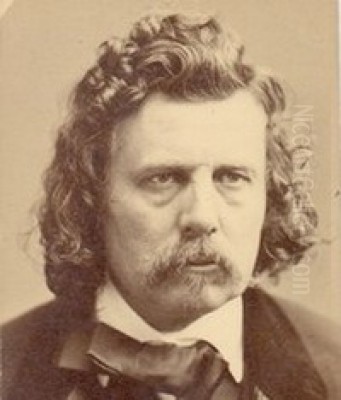

William Holbrook Beard stands as a unique figure in the landscape of nineteenth-century American art. Born on April 13, 1825, in Painesville, Ohio, and passing away in New York City on February 20, 1900, Beard carved a distinct niche for himself through his imaginative, humorous, and often sharply satirical paintings featuring animals behaving remarkably like humans. While his contemporaries in the Hudson River School were capturing the sublime grandeur of the American wilderness, Beard turned his keen observational skills and witty intellect towards the animal kingdom, using it as a mirror to reflect the follies, vanities, and vices of humankind. His work, popular in its day, offers a fascinating blend of technical skill, imaginative storytelling, and social commentary.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Beard's artistic journey began not with the bears and monkeys that would later define his career, but with the more conventional path of portraiture. Like many aspiring artists of his time, he initially sought commissions painting the likenesses of his fellow citizens. He worked as an itinerant portrait painter in Ohio and possibly other states during his early years. However, the market for portraits, particularly outside major metropolitan centers, could be precarious. Sources suggest that Beard found the demand insufficient or perhaps the work itself less fulfilling than his burgeoning interest in other subjects.

This early period, though less documented than his later fame, was crucial in honing his technical skills in drawing and painting the human (and soon, animal) form. The discipline required for portraiture – capturing likeness, understanding anatomy, rendering textures – provided a solid foundation for the detailed and believable, albeit fantastical, animal scenes he would later create. His Ohio roots placed him geographically distant from the burgeoning art centers of the East Coast, likely necessitating self-reliance and resourcefulness in his early artistic development.

European Sojourn and Broadening Horizons

Seeking to refine his skills and broaden his artistic horizons, Beard, like many ambitious American artists of his generation, traveled to Europe in the mid-1850s. This period was transformative. He spent significant time in Germany, particularly in Düsseldorf, a major center for academic art training that attracted numerous American painters. The Düsseldorf School emphasized meticulous detail, careful finish, and often narrative or historical subjects. While Beard's later subject matter would diverge significantly from typical Düsseldorf historical epics, the emphasis on precise rendering likely reinforced his own inclinations towards detailed realism, even when applied to whimsical scenarios.

During his time abroad, from roughly 1856 to 1858, Beard associated with fellow American artists who were also studying or traveling. Notably, he formed connections with landscape painters like Albert Bierstadt and Thomas Worthington Whittredge. Bierstadt, who also spent time in Düsseldorf, would go on to achieve immense fame for his dramatic, large-scale paintings of the American West, while Whittredge, another Düsseldorf alumnus, became a respected member of the Hudson River School. These interactions exposed Beard to different artistic currents and likely involved shared experiences and discussions about art and the European scene. His travels also took him to Italy and Switzerland, further exposing him to both Old Masters and the stunning natural landscapes that inspired the Romantic movement.

New York City and National Recognition

Upon returning to the United States, Beard did not immediately settle on the East Coast. He worked for a period in Buffalo, New York, further developing his unique style. However, the magnetic pull of New York City, rapidly solidifying its position as the undisputed center of the American art world, proved irresistible. In 1861, Beard made the pivotal move to New York, establishing a studio and immersing himself in the city's vibrant artistic community.

His arrival coincided with a period of great artistic energy, despite the looming Civil War. He likely found studio space, perhaps initially or later, in the famed Tenth Street Studio Building, a purpose-built structure that housed studios for many of the era's leading artists, including Bierstadt, Frederic Edwin Church, Sanford Robinson Gifford, and Eastman Johnson. This environment fostered collaboration, competition, and the exchange of ideas. Beard's unique brand of animal satire quickly gained attention. In 1862, his growing reputation was cemented by his election as a full member (Academician) of the prestigious National Academy of Design, a key institution for exhibiting work and gaining professional standing. This recognition signaled his acceptance into the upper echelons of the American art establishment. It's also noteworthy that his older brother, James Henry Beard, was also a successful painter, known particularly for his own animal portraits and genre scenes, creating a unique family dynamic within the art world.

The Anthropomorphic Menagerie: Style and Signature Themes

William Holbrook Beard's artistic signature lies in his masterful use of anthropomorphism – attributing human characteristics, emotions, and behaviors to animals. He possessed a remarkable ability to render animals with anatomical accuracy while simultaneously imbuing them with expressions and postures that spoke volumes about human nature. Bears became a particular favorite, perhaps due to their imposing yet somehow relatable form, allowing for a wide range of expressive possibilities.

His paintings often depict animals engaged in distinctly human activities, frequently those associated with leisure, social rituals, or even outright debauchery. Works like The Bear Dance or Dancing Bears show these creatures awkwardly but joyfully mimicking human festivities. Bears on a Bender takes the satire further, depicting bears succumbing to the effects of alcohol, a clear critique of human intemperance. Through these humorous scenarios, Beard gently, and sometimes not so gently, poked fun at human social conventions, pretensions, and weaknesses.

His style combined meticulous, almost academic, realism in the rendering of fur, feathers, and form with a fantastical, narrative imagination. The settings could range from realistic forest clearings to more allegorical or stage-like environments. The humor was often immediate and accessible, but beneath the surface lay a layer of pointed social commentary. He observed the world around him with a satirist's eye, translating human foibles – pride, greed, foolishness, revelry – into the visual language of the animal kingdom. This approach proved highly popular with audiences who enjoyed both the technical skill and the witty narratives.

Wall Street and the Critique of Speculation

Among Beard's most famous and enduring works is The Bulls and Bears in the Market, sometimes titled The Bulls and Bears of Wall Street. Painted in 1879, this work directly tackles the frenetic and often ruthless world of financial speculation that characterized the Gilded Age. Using the now-commonplace animal metaphors for market trends – the aggressive, charging bull representing rising prices and the defensive, swiping bear representing falling prices – Beard created a chaotic scene outside the New York Stock Exchange.

In the painting, elegantly dressed bulls and bears engage in a frantic, almost violent, struggle. Papers litter the ground, top hats are askew, and the animals' expressions convey greed, panic, and aggression. It is a powerful visual metaphor for the booms and busts, the fortunes made and lost, in the burgeoning financial markets of post-Civil War America. The painting transcends simple humor; it is a sharp critique of the speculative mania, avarice, and potential for ruin inherent in the system. Its popularity speaks to the public's fascination with, and perhaps anxiety about, the world of high finance. This work cemented Beard's reputation as not just an animal painter, but a keen social commentator capable of using his unique style to address contemporary issues. Other artists, like John George Brown who painted street urchins, also captured aspects of New York life, but Beard's allegorical approach was distinct.

Beyond Satire: Landscapes and Allegory

While best known for his satirical animal scenes, William Holbrook Beard's artistic output was more diverse than often acknowledged. He continued to paint landscapes throughout his career, likely influenced by his associations with Hudson River School painters and his travels through scenic regions of Europe and America. Though perhaps overshadowed by the works of specialists like Thomas Cole or Asher B. Durand, his landscapes demonstrate a sensitivity to nature and competent handling of light and atmosphere.

Furthermore, Beard occasionally tackled grander, more somber themes. One notable example is the large-scale allegorical work The Power of Death (also known as The Death of the First Born). This painting, quite different in tone from his usual humorous fare, demonstrates his ambition to engage with profound subjects in a more traditional, academic manner. While details about this specific work are less circulated than his satires, its existence highlights his versatility and his engagement with the broader artistic conventions of the time, which still valued historical and allegorical painting. This diversity shows an artist exploring different modes of expression beyond the niche that brought him the most fame.

Artistic Circles and Context

Beard operated within a rich network of artists in New York. His connections with Albert Bierstadt and Thomas Worthington Whittredge, forged in Europe, continued in America. He was part of the milieu associated with the Hudson River School, even if his primary subject matter differed. He would have known, exhibited alongside, and interacted with key figures of that movement and the broader New York art scene. This included not only the landscape painters but also genre painters like Eastman Johnson and Winslow Homer, who were also chronicling aspects of American life, albeit through different lenses.

His satirical approach, while unique in American painting, had precedents in European graphic arts and illustration. The French artist J.J. Grandville (Jean Ignace Isidore Gérard) was renowned for his witty and often politically charged drawings of animals and objects endowed with human characteristics. In Germany, artists like Wilhelm von Kaulbach also employed animal allegories. While direct influence is hard to pinpoint, Beard worked within an international tradition of using animal imagery for satirical and moralizing purposes, adapting it to an American context and elevating it to the medium of oil painting with considerable technical skill.

Science, Belief, and the Darwin Debate

The latter half of the nineteenth century was a period of intense intellectual ferment, particularly following the publication of Charles Darwin's On the Origin of Species in 1859. Darwin's theory of evolution by natural selection challenged long-held religious and philosophical beliefs about humanity's place in the natural order and the nature of animals. William Holbrook Beard entered this debate from a position of skepticism towards evolutionary theory.

Sources indicate that Beard held a belief that animals possessed souls and were capable of expressing emotions akin to humans – a view somewhat at odds with purely mechanistic interpretations of animal behavior and more aligned with a Romantic sensibility. His anthropomorphic paintings, in a way, visually represented this belief. Reportedly, he painted a specific work featuring monkeys explicitly intended to satirize or critique Darwin's ideas, likely focusing on the perceived absurdity or indignity of a close relationship between humans and apes. This stance places Beard within a segment of society, including some artists and intellectuals, who resisted the implications of Darwinism, reflecting the broader cultural anxieties and debates sparked by the new scientific theories.

Later Years and Evolving Style

As Beard grew older, his connection to the wild subjects he sometimes depicted naturally lessened. While he had undertaken trips earlier in his career to observe animals, his later work increasingly relied on his established formulas, accumulated knowledge, and pure imagination. Some critics suggest a shift towards a more conventional or academic style in his later years, perhaps moving slightly away from the raw energy of his most biting satires.

However, he remained an active figure in the New York art world and continued to produce work. His reputation as the preeminent painter of humorous animal satire was secure. Even if the novelty slightly wore off for some critics over time, his paintings continued to find buyers and admirers. He maintained his studio and continued exhibiting, contributing to the artistic life of the city until the end of the century. His dedication to his unique vision remained constant, even as artistic tastes began to shift with the rise of Impressionism and other modern movements, which Beard largely did not engage with in his own work.

Death, Burial, and Lasting Legacy

William Holbrook Beard died in New York City on February 20, 1900. He was buried in the historic Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, a place where many prominent New Yorkers, including fellow artists like Asher B. Durand and George Catlin, were laid to rest. For many years, however, Beard's grave remained unmarked, a surprising oversight given his prominence during his lifetime.

Over a century after his death, his resting place received proper recognition thanks to the efforts of Green-Wood historian Jeffrey Richman. Recognizing Beard's significance and his particular affinity for bears, Richman spearheaded a project to place a fitting memorial. In 2003, a granite bench was installed, and notably, sculptor Dan Osterman donated a charming bronze sculpture of a seated bear, which now presides over the site – a perfect tribute to the artist who found so much inspiration in these creatures.

Beard's legacy is that of a highly skilled painter who carved out a unique and memorable niche in American art. His work is represented in major museum collections, including the New-York Historical Society, the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, the Buffalo AKG Art Museum (formerly Albright-Knox Art Gallery), and the Smithsonian American Art Museum. While perhaps not always afforded the same critical weight as the leading landscape or figure painters of his era, his satirical animal paintings remain distinctive, engaging, and historically significant. They offer a witty and insightful commentary on American society during a period of rapid change and continue to amuse and provoke thought today. He demonstrated that animal painting could be a vehicle for sophisticated social critique and enduring humor.

Conclusion: An American Original

William Holbrook Beard remains a fascinating and somewhat anomalous figure in the grand narrative of American art history. He successfully navigated the art worlds of Ohio, Europe, and New York, achieving recognition from esteemed institutions like the National Academy of Design. Eschewing the dominant trends of landscape painting and historical epics, he cultivated a highly personal style focused on anthropomorphic animals, using humor and satire to comment on the human condition. From the boisterous revelry of his bears to the sharp critique of Wall Street speculation, his paintings provide a unique window into the social attitudes and cultural preoccupations of the Gilded Age. Though sometimes viewed as eccentric, his technical skill was undeniable, and his imaginative vision secured him a lasting, if specialized, place in the annals of American art. His work continues to charm viewers and remind us of the power of art to critique and entertain through unconventional means.