Marinus Claeszoon van Reymerswaele (circa 1490/1495 – circa 1546/1567) stands as a significant, if somewhat enigmatic, figure in the landscape of 16th-century Netherlandish Renaissance painting. Known for a distinctive and focused oeuvre, he carved a niche for himself with his incisive, often satirical, depictions of financial and legal professionals, alongside more traditional religious themes, particularly renderings of Saint Jerome. His work offers a fascinating window into the societal anxieties, moral concerns, and burgeoning capitalism of his era, particularly in the bustling commercial centers of the Low Countries.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born in the town of Reimerswaal in Zeeland, a province in the southwestern Netherlands, Marinus's early life is sparsely documented. His father, Claes van Zierikzee, was also a painter, suggesting an early immersion in an artistic environment. The town of Reimerswaal itself, a once-thriving port, faced a precarious existence due to recurrent storm floods, and was eventually abandoned in the 17th century. This backdrop of a community grappling with the forces of nature might have subtly informed an artist keenly observant of life's transience.

Records indicate that Marinus may have enrolled at the University of Leuven in 1504, listed as "Morynus Nicolai de Reymerswael." While it's uncertain if this was the painter, a university education, even if brief, could have exposed him to humanist thought, which often underpinned Renaissance art. His formal artistic training is believed to have occurred possibly under the tutelage of the "glasschilder" (glass painter) Simon van Dale of Antwerp in 1509. Antwerp, by this time, was rapidly becoming the economic and artistic heart of Northern Europe, attracting talent from across the continent.

Antwerp: A Crucible of Commerce and Art

Marinus van Reymerswaele's most productive years were spent in Antwerp, a city teeming with merchants, bankers, and international trade. This environment provided fertile ground for his characteristic themes. He is documented as a painter in Antwerp, where he likely established a successful workshop. The city's dynamic commercial life, with its newly prominent figures of money lenders, tax collectors, and lawyers, became a central focus of his art. These professions, while essential to the burgeoning economy, were often viewed with suspicion and moral condemnation, a sentiment Marinus expertly captured.

His style is characterized by a meticulous attention to detail, a hallmark of Netherlandish painting inherited from masters like Jan van Eyck and Rogier van der Weyden. However, Marinus pushed this realism towards caricature, particularly in the expressive, often grotesque, faces and gesticulating hands of his subjects. His figures are typically depicted in cramped, cluttered interiors, surrounded by the paraphernalia of their trades – coins, ledgers, documents, and inkwells – all rendered with painstaking precision.

Thematic Focus: A Mirror to Society

Marinus van Reymerswaele's body of work is remarkably consistent in its thematic concerns, primarily revolving around a few key subjects which he revisited multiple times, often with subtle variations. This repetition suggests a strong market demand for these particular images, likely from a clientele that appreciated their moralizing or satirical content.

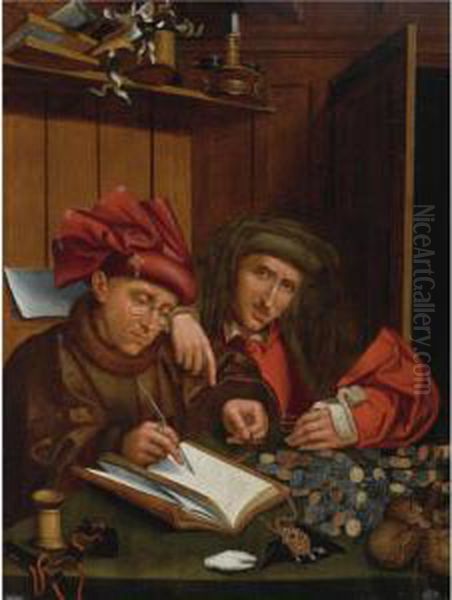

The World of Finance: Tax Collectors and Money Changers

Perhaps his most iconic works are those depicting tax collectors and money changers. The Tax Collectors (versions in the National Gallery, London; Louvre, Paris; and Alte Pinakothek, Munich, among others) typically shows two men, often with exaggerated, almost predatory features, hunched over a table strewn with coins and account books. Their expressions range from avaricious glee to cunning suspicion, their gnarled hands eagerly counting or grasping money. These paintings served as potent critiques of greed and financial exploitation, resonating with contemporary anxieties about usury and the perceived moral decay associated with the pursuit of wealth.

Similarly, The Money Changer and His Wife (versions in the Prado, Madrid; and the Hermitage, St. Petersburg) draws on a theme popularized by Quentin Matsys, an older Antwerp contemporary whose 1514 painting of the same subject is a landmark. Marinus’s interpretations, however, often amplify the satirical edge. The wife, sometimes appearing younger and more elegantly dressed, might be shown observing her husband's activities with a detached or complicit air, or even actively participating. The meticulous rendering of coins, scales, and ledgers underscores the obsession with material wealth, while the figures' expressions hint at the moral compromises involved. These works can be seen as visual sermons on the biblical warning, "You cannot serve both God and mammon."

Critique of the Legal Profession: The Lawyer's Office

Another recurring subject is The Lawyer's Office (versions in the New Orleans Museum of Art and the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Valenciennes). These paintings depict lawyers, often elderly and bespectacled, surrounded by clients and heaps of legal documents. The atmosphere is one of bureaucratic entanglement and potential chicanery. Clients often appear bewildered or desperate, while the lawyers exude an air of self-importance or sly calculation. In one version, a document depicted is an actual record of a salt marsh lawsuit from Reimerswaal dated 1526, grounding the satire in specific, recognizable realities. These works tap into a long-standing societal distrust of the legal profession, portraying it as a realm of obfuscation and exploitation rather than justice. The detailed rendering of parchments, seals, and quills emphasizes the complex and often inaccessible nature of the law for the common person.

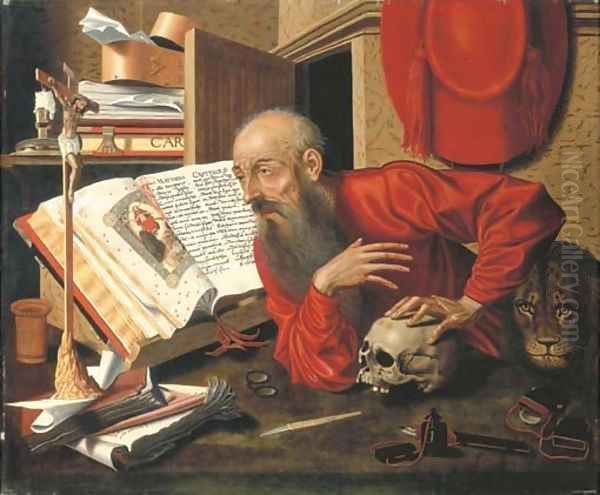

Religious Devotion and Scholarship: Saint Jerome

Alongside his secular satires, Marinus produced numerous depictions of Saint Jerome in His Study or Saint Jerome in Penitence (versions in the Prado, Madrid; Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp; and Gemäldegalerie, Berlin). Saint Jerome, one of the four Latin Doctors of the Church, was a popular subject in Renaissance art, revered for his translation of the Bible into Latin (the Vulgate) and his scholarly asceticism. Marinus typically portrays Jerome as an emaciated, elderly figure, either engrossed in his studies or in fervent prayer, often accompanied by his traditional attributes: the lion, the cardinal's hat (anachronistically, as he was not a cardinal), a crucifix, a skull (memento mori), and an hourglass or snuffed-out candle symbolizing the transience of life.

These paintings, while seemingly devotional, often carry a similar intensity to his secular works. Jerome's gaunt features and fervent expression convey a profound spiritual struggle. The cluttered study, filled with books and writing implements, highlights his scholarly pursuits, but the ever-present skull serves as a stark reminder of mortality and the vanity of worldly endeavors. It's possible that these images of intense piety and renunciation of the world offered a moral counterpoint to his depictions of worldly greed. The influence of Albrecht Dürer's famous engravings of Saint Jerome is palpable in some of Marinus's compositions, particularly in the meticulous rendering of the study's interior and symbolic objects.

The Call to a Different Life: The Calling of Saint Matthew

Another significant religious theme in Marinus's oeuvre is The Calling of Saint Matthew (versions in the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna; and the Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte, Naples). The biblical story tells of Jesus calling Matthew, a tax collector, to become one of his apostles. This theme allowed Marinus to combine his interest in the world of finance with a narrative of spiritual transformation. Matthew is typically shown at his tax collector's table, surrounded by coins and ledgers, interrupted by the figure of Christ. The contrast between the worldly concerns of Matthew's profession and the spiritual call of Jesus creates a dramatic tension. These paintings explore themes of redemption and the possibility of turning away from material pursuits towards a life of faith, a message that would have resonated strongly during the turbulent religious climate of the Reformation. The work of earlier Netherlandish artists like Jan Sanders van Hemessen, who also depicted scenes with tax collectors and parables, might have provided some thematic parallels.

Artistic Style and Technique

Marinus van Reymerswaele's style is highly distinctive. He worked primarily in oil on panel, employing a precise, linear technique. His figures are often elongated, with bony, expressive hands and faces that verge on caricature. He had a particular fondness for depicting aged skin, with wrinkles and sinews meticulously rendered. His color palette tends towards rich, often somber tones, with occasional flashes of brighter color in clothing or drapery.

A key characteristic is the almost claustrophobic compression of figures within the pictorial space. His interiors are invariably cluttered, filled with objects that are not merely decorative but contribute to the narrative and symbolic meaning of the scene. This density of detail invites close scrutiny from the viewer, encouraging a deeper engagement with the painting's message. While his figures can appear somewhat stiff or mannered, their psychological intensity is undeniable. He was less concerned with idealized beauty, a hallmark of the Italian Renaissance, and more focused on expressive characterization, aligning him with a Northern European tradition that valued verisimilitude and moral commentary. Artists like Hieronymus Bosch and Pieter Bruegel the Elder, though different in their overall scope, shared this inclination towards moralizing genre and a keen observation of human folly.

Influences and Contemporaries

The most direct artistic influence on Marinus van Reymerswaele was undoubtedly Quentin Matsys (c. 1466–1530). Matsys, a leading figure in the Antwerp school, pioneered many of the themes that Marinus would later adopt, particularly the depiction of money changers and satirical portraits. Marinus clearly studied Matsys's compositions, often borrowing motifs and arrangements, but typically pushed the element of caricature further, making his figures more overtly grotesque or avaricious.

While Marinus focused on a relatively narrow range of subjects, the artistic environment of Antwerp was incredibly diverse. Joachim Patinir, a pioneer of landscape painting, was active in Antwerp during Marinus's early career. Jan Gossaert (Mabuse) introduced Italianate forms and mythological subjects to Netherlandish art. Bernard van Orley in Brussels was a versatile artist working in tapestry design, portraiture, and religious painting. Lucas van Leyden, active in Leiden, was a renowned painter and printmaker whose genre scenes and expressive figures also explored aspects of everyday life and human character.

Later in the 16th century, artists like Pieter Aertsen and his nephew Joachim Beuckelaer developed the genre of market and kitchen scenes, often embedding religious narratives within bustling depictions of everyday life and produce. While their focus was different, they shared with Marinus an interest in the material world and its moral implications. The legacy of Marinus's satirical genre scenes can be seen, albeit transformed, in the later works of 17th-century Flemish and Dutch genre painters like Adriaen Brouwer and David Teniers the Younger, who depicted peasant life with a similar, though often more humorous, earthiness.

The Workshop and Replication

The existence of multiple versions of Marinus's most popular compositions, with varying degrees of quality and minor differences in detail, strongly suggests the operation of a productive workshop. This was a common practice in the 16th century, allowing artists to meet market demand and disseminate their work more widely. Assistants would have helped in producing copies or variants under the master's supervision. This practice can sometimes make definitive attributions challenging, with scholars debating the extent of Marinus's direct involvement in every surviving version. However, the consistency of style and thematic preoccupation across these works points to a singular artistic vision at their core.

The demand for these specific images – the grasping tax collector, the scholarly saint, the morally compromised lawyer – indicates that they struck a chord with contemporary audiences. They served as conversation pieces, moral exemplars, or objects of private devotion, reflecting the concerns and tastes of a society grappling with rapid economic change and religious upheaval.

Later Years and Controversies

Information about Marinus's later life remains somewhat obscure. He is believed to have left Antwerp and returned to Zeeland. Some sources suggest he moved to Middelburg. A "Marinus de schildere" (Marinus the painter) from Reimerswaal is recorded in Middelburg in 1540 as being sentenced to a six-year banishment from the city for participating in the plundering of the Westmonsterkerk (West Minster Church) during an iconoclastic riot. If this was indeed Marinus van Reymerswaele, it adds a dramatic and controversial chapter to his biography, placing him directly in the midst of the religious conflicts that were beginning to sweep through the Netherlands. The iconoclasm, a wave of destruction of religious images, was a feature of the Protestant Reformation.

The exact date of his death is uncertain. Traditionally, it was placed around 1546, but some scholars argue for a later date, possibly as late as 1567 or even beyond, based on stylistic analysis and the dating of some of his works. His birthplace, Reimerswaal, suffered catastrophic floods in 1530 and 1532 and was largely abandoned by the mid-16th century, a poignant end for the town that gave him his name.

Legacy and Art Historical Standing

For a long time, Marinus van Reymerswaele was a somewhat overlooked figure, often seen primarily as a follower of Quentin Matsys. However, modern scholarship has increasingly recognized his unique contribution to Netherlandish art. His focused thematic repertoire, his distinctive style blending meticulous realism with sharp caricature, and his insightful commentary on the social and moral issues of his time set him apart.

His paintings are now found in major museums worldwide, including the Prado in Madrid (which holds a significant collection of his works), the Louvre in Paris, the National Gallery in London, the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, and the Hermitage in St. Petersburg. Exhibitions and scholarly publications have shed further light on his career and the context in which he worked.

Marinus van Reymerswaele's art serves as a powerful visual record of a society in transition. His depictions of financiers and lawyers capture the anxieties surrounding the rise of capitalism and the perceived erosion of traditional moral values. His images of Saint Jerome, on the other hand, reflect a continuing devotion to scholarly piety and a yearning for spiritual certainty in an age of religious turmoil. He was not merely a painter of surfaces, but a keen observer and critic of human nature, whose work continues to engage and provoke viewers centuries later. His ability to infuse genre scenes with such potent moral and satirical weight makes him a crucial figure in understanding the development of Northern European painting.

Conclusion

Marinus van Reymerswaele remains a compelling artist whose work bridges the late Gothic tradition of detailed realism with the emerging concerns of the Renaissance and Reformation. His sharp, often unsettling, portrayals of tax collectors, money changers, and lawyers, contrasted with his intense depictions of Saint Jerome, offer a multifaceted view of 16th-century Netherlandish society. He masterfully used his brush to explore themes of avarice, justice, piety, and the human condition, leaving behind a legacy of images that are as historically informative as they are artistically distinctive. His focused vision and incisive social commentary ensure his enduring place in the annals of art history, a unique voice from a transformative era.