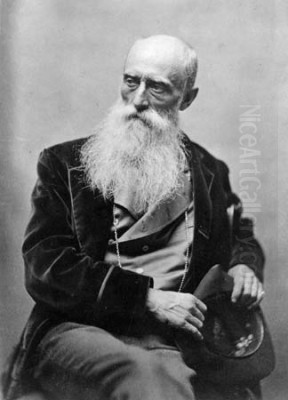

William Morris Hunt (March 31, 1824 – September 8, 1879) stands as a pivotal, if sometimes underappreciated, figure in the landscape of nineteenth-century American art. A charismatic painter, influential teacher, and passionate promoter of European artistic trends, Hunt played a crucial role in shifting American artistic tastes away from the detailed realism of the Hudson River School towards a more painterly, subjective, and European-influenced aesthetic, particularly that of the French Barbizon School. His life was one of privilege and travel, marked by significant artistic achievements, influential relationships, and ultimately, a tragic end.

Early Life and European Awakening

Born in Brattleboro, Vermont, into a prominent and wealthy family, William Morris Hunt enjoyed an upbringing that afforded him numerous opportunities. His father, Jonathan Hunt, was a U.S. Congressman, and his mother, Jane Maria Leavitt Hunt, was a woman of culture and determination who, after her husband's early death, took her children to Europe for their education. His brother, Richard Morris Hunt, would go on to become one of America's most celebrated architects, known for designing the Biltmore Estate and the facade of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Initially, William attended Harvard College but left due to ill health and a disinclination towards a traditional academic path. His artistic inclinations led him, with his mother's encouragement, to Europe in 1843. He first considered sculpture, briefly studying in Rome, but soon found his true calling in painting. This decision set him on a course that would profoundly shape his artistic vision and, subsequently, the direction of art in his native country.

Parisian Studies: Couture and the Academic Tradition

In 1846, Hunt arrived in Paris, the undisputed center of the art world at the time. He initially enrolled in the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts but found its rigid academicism stifling. He soon sought out the atelier of Thomas Couture, a highly respected painter whose work Romans of the Decadence (1847) had caused a sensation at the Salon. Couture, while himself a product of the academic system, encouraged a more direct and painterly approach than many of his contemporaries, emphasizing strong drawing, clear composition, and a fresh application of paint.

Hunt thrived under Couture's tutelage for several years, absorbing lessons in technique and composition. Couture's method involved a clear underpainting, followed by layers of color applied with a certain bravura. This training provided Hunt with a solid technical foundation. Other American artists, such as Eastman Johnson, also passed through Couture's studio, though Hunt's engagement was particularly deep. However, while Couture's influence was significant, Hunt's artistic soul was yearning for something more personal and emotionally resonant.

The Barbizon Revelation: Jean-François Millet

The turning point in Hunt's artistic development came with his encounter with the art of Jean-François Millet. Around 1851, Hunt saw Millet's painting The Sower and was profoundly moved by its dignity, monumentality, and sympathetic portrayal of peasant life. He sought out Millet in the village of Barbizon, on the edge of the Forest of Fontainebleau, which had become a haven for artists seeking to escape the confines of Paris and paint directly from nature.

Hunt became a devoted admirer, friend, and patron of Millet, purchasing several of his works, including The Sower and The Sheep Shearers. He spent considerable time in Barbizon, working alongside Millet and absorbing his philosophy. Millet, along with other Barbizon painters like Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, Théodore Rousseau, Charles-François Daubigny, and Narcisse Virgilio Díaz de la Peña, advocated for a more intimate and poetic approach to landscape and genre painting, emphasizing mood, atmosphere, and the humble beauty of rural life. Hunt was particularly drawn to Millet's depiction of the human figure within the landscape, imbued with a sense of timeless gravity. This immersion in the Barbizon ethos would become the defining influence on Hunt's own art and his mission upon returning to America.

Return to America: Championing a New Aesthetic

William Morris Hunt returned to the United States in 1855, first settling in Newport, Rhode Island, before establishing himself in Boston in 1862. He brought with him not only his own evolving artistic style but also a fervent desire to introduce the Barbizon aesthetic to an American audience largely dominated by the meticulous detail of the Hudson River School painters, such as Albert Bierstadt and Frederic Edwin Church, and the genre scenes of artists like Eastman Johnson.

Hunt became a vocal proponent of French art, particularly the works of Millet and Corot. He encouraged wealthy Bostonians to collect these artists, thereby helping to build some of the earliest and most significant collections of Barbizon art in America. His own paintings from this period, such as The Belated Kid (c. 1857) and Girl at the Fountain (1852-54), clearly reflect Millet's influence in their subject matter, somber palette, and emphasis on simplified forms and emotional depth. These works stood in stark contrast to the prevailing American taste, offering a more introspective and less overtly narrative vision.

A Boston Institution: Painting and Pedagogy

In Boston, Hunt quickly became a leading figure in the city's burgeoning art scene. He was a successful portrait painter, sought after by prominent Bostonians for his ability to capture not just a likeness but also the character of his sitters. His portraits, such as that of Chief Justice Lemuel Shaw, demonstrate a sophisticated understanding of form and a painterly handling that was fresh and modern for its time. He also continued to paint landscapes and genre scenes, often imbued with the poetic sensibility he had absorbed in Barbizon.

Perhaps equally important was Hunt's role as a teacher. He established an art school for women, a progressive move at the time, and his classes were immensely popular. He was a charismatic and inspiring instructor, encouraging his students to develop their own individual styles rather than merely imitating his own. He emphasized direct observation, the importance of capturing the overall impression, and the expressive potential of color and brushwork. Among his notable students were Helen M. Knowlton (who later became his biographer), Ellen Day Hale, and indirectly, Childe Hassam, who was influenced by the artistic environment Hunt helped create. John La Farge, a contemporary and friend, shared Hunt's interest in European art and also became an influential figure, particularly in stained glass and mural painting.

Artistic Style and Representative Works

Hunt's artistic style is characterized by its breadth, its tonal harmonies, and its focus on capturing the essential character or mood of a subject rather than an accumulation of minute details. His early work shows the polish of Couture, but his mature style is deeply indebted to Millet and the Barbizon School. He favored relatively subdued palettes, often employing rich browns, grays, and greens, with an emphasis on the play of light and shadow to create atmosphere.

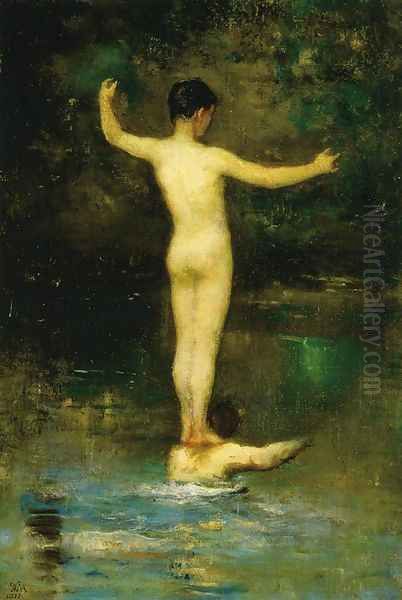

The Belated Kid (c. 1857, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston): This painting, depicting a young farm girl carrying a kid goat against a twilight sky, is a quintessential example of Hunt's Barbizon-influenced work. The sentiment is gentle, the forms are simplified, and the mood is one of quiet rural life.

Girl at the Fountain (1852-54, Metropolitan Museum of Art): Painted during his time in France, this work shows a pensive young woman, her form solid and sculptural, reflecting Millet's influence in its dignity and simplicity.

Portrait of Lemuel Shaw (1859, Essex Institute, Salem): A powerful and insightful portrait of the Chief Justice of the Massachusetts Supreme Court, showcasing Hunt's skill in capturing personality with a direct and unpretentious approach.

The Flight of Night and The Discoverer (1878, formerly New York State Capitol, Albany): These were two monumental allegorical murals, his most ambitious public works. Though tragically destroyed by fire, studies and photographs remain, revealing his capacity for grand-scale composition and imaginative design. The Flight of Night depicted a goddess driving a chariot through the night sky, while The Discoverer showed Columbus on his ship.

His landscapes, often depicting scenes around New England, are characterized by their atmospheric quality and painterly freedom, prefiguring some aspects of American Impressionism. He was less interested in the sublime grandeur of the Hudson River School and more focused on the intimate, poetic aspects of nature, much like Corot or Daubigny.

The Albany Murals: Ambition and Tragedy

In the late 1870s, Hunt received his most significant commission: to paint two large lunette murals for the Assembly Chamber of the New York State Capitol in Albany. The subjects were allegorical: The Flight of Night (representing the progress of civilization banishing darkness) and The Discoverer (symbolizing exploration and enterprise, featuring a figure of Columbus). This was a monumental undertaking, requiring Hunt to work on an unprecedented scale.

He threw himself into the project with immense energy, experimenting with different techniques and working with a team of assistants. The murals, completed in 1878, were painted directly onto the stone walls and were initially hailed as masterpieces, representing a significant step forward for public art in America. They showcased Hunt's ability to handle complex compositions and allegorical themes with a powerful, painterly style. Tragically, due to structural problems with the building and subsequent renovations, the murals were covered over and eventually destroyed when the ceiling collapsed. This loss was a severe blow to Hunt and to American art history.

The Great Boston Fire and Personal Setbacks

Another significant setback in Hunt's life was the Great Boston Fire of 1872. The fire devastated a large portion of the city, and Hunt's studio, along with many of his own paintings and his valuable collection of works by Millet and other European artists, was destroyed. This was not only a personal and financial loss but also a cultural one, as it deprived Boston of many important artworks.

These professional disappointments, coupled with periods of depression and ill health, took a toll on Hunt. His energetic and often intense personality could also lead to periods of despondency. The immense physical and mental strain of the Albany mural project, followed by criticisms and the looming threat to their permanence, likely exacerbated his fragile emotional state.

Interactions with Contemporaries

Hunt was a central figure in the Boston art world and had numerous interactions with other artists. His advocacy for Millet, Corot, and the Barbizon school directly influenced collectors and fellow painters. He was a friend to John La Farge, who also looked to European precedents and explored mural painting and stained glass. Elihu Vedder, known for his mystical and symbolic works, was one of Hunt's early students in Newport and acknowledged his influence.

While Hunt championed a style different from the prevailing Hudson River School, he was part of a broader American art scene that included figures like Winslow Homer, whose work was evolving towards a powerful realism, and George Inness, who, like Hunt, was deeply influenced by the Barbizon School and developed a distinctive tonalist style. Hunt's efforts helped to create a more receptive environment for European modernism, paving the way for later American artists who would study in Paris, such as James McNeill Whistler (though largely an expatriate), John Singer Sargent, and Mary Cassatt. His promotion of a more subjective and painterly approach can be seen as a precursor to the eventual embrace of Impressionism in America, championed by artists like Childe Hassam and Theodore Robinson.

Later Years and Untimely Demise

The destruction of his Albany murals, or at least the knowledge of their impending doom due to the faulty architecture, weighed heavily on Hunt. He suffered from severe depression in his later years. In the summer of 1879, while visiting his friend Celia Thaxter on the Isles of Shoals, off the coast of New Hampshire, William Morris Hunt died. He was found drowned in a shallow cistern. While the exact circumstances remain somewhat ambiguous, it is widely believed to have been a suicide, a tragic end for an artist who had contributed so much to American culture. He was only 55 years old.

His death was mourned by the artistic community, and his contributions were recognized in numerous tributes. His student and confidante, Helen M. Knowlton, published "Art-Life of William Morris Hunt" in 1899, providing valuable insights into his methods and philosophies.

Legacy and Influence

William Morris Hunt's influence on American art was profound and multifaceted. He was instrumental in introducing and popularizing the Barbizon aesthetic in the United States, shifting tastes away from the tight precision of earlier styles towards a more expressive and painterly approach. His advocacy for artists like Millet and Corot enriched American collections and broadened artistic horizons.

As a teacher, he inspired a generation of artists, particularly women, encouraging them to find their own voices and embrace modern European ideas. His emphasis on capturing the "impression" and his painterly technique can be seen as laying some of the groundwork for the later acceptance of Impressionism in America. Artists like Dennis Miller Bunker, who would go on to embrace Impressionism, were part of the Boston scene that Hunt had helped to shape. Even artists who pursued different paths, such as Thomas Eakins with his uncompromising realism, or Albert Pinkham Ryder with his deeply personal and visionary style, were part of an American art world that was becoming more diverse and open to various influences, a trend Hunt actively fostered.

Though some of his most ambitious works, like the Albany murals, were tragically lost, his surviving portraits, landscapes, and genre scenes attest to his skill and artistic vision. He helped to elevate the status of the artist in America and fostered a more cosmopolitan outlook in cities like Boston. William Morris Hunt remains a key figure in understanding the transition of American art in the mid-to-late nineteenth century, a bridge between native traditions and the progressive currents of European art. His passion, talent, and dedication left an indelible mark on the cultural landscape of his time and on the artists who followed. His work continues to be studied and appreciated for its artistic merit and its historical significance in the story of American art, influencing figures like Frank Duveneck and William Merritt Chase who furthered the cause of painterly realism and international artistic exchange.