William Morris (1834-1896) stands as one of the most formidable and influential figures of the 19th century, a true polymath whose talents spanned poetry, design, craftsmanship, social activism, and entrepreneurship. His profound impact on the visual arts, particularly through his leadership of the Arts and Crafts Movement, continues to resonate today. Morris championed the value of handcrafted objects, the beauty of nature, and the dignity of the worker, offering a powerful critique of the industrialised society of Victorian England. His life and work represent a passionate quest for beauty, utility, and social justice, leaving an indelible mark on design, literature, and political thought.

Early Life and Oxford Awakening

Born on March 24, 1834, in Walthamstow, Essex, then a village on the outskirts of London, William Morris was the son of a wealthy financier. His affluent upbringing allowed him access to a comfortable life and extensive education. The family's move to Woodford Hall, with its adjacent Epping Forest, provided young Morris with an early and profound connection to the natural world, an influence that would permeate his later artistic creations. He was an avid reader, devouring the romantic novels of Sir Walter Scott and developing a fascination with medieval history, chivalry, and architecture.

This interest in the medieval past deepened during his studies at Exeter College, Oxford, which he entered in 1853. Initially intending to take holy orders, Morris's path diverged significantly. At Oxford, he formed a pivotal friendship with Edward Burne-Jones, who would become a lifelong collaborator and a leading painter of the second wave of Pre-Raphaelitism. Together, they immersed themselves in medieval literature, art, and the writings of social critics like Thomas Carlyle and, crucially, John Ruskin. Ruskin's "The Stones of Venice," with its chapter "The Nature of Gothic," became a sacred text for them, championing the joy of medieval craftsmanship and decrying the dehumanising effects of industrial labour.

Through Burne-Jones, Morris was introduced to Dante Gabriel Rossetti, a charismatic founder of the original Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. This group, which also included John Everett Millais and William Holman Hunt, had sought to revitalise British art by rejecting the academic conventions of the Royal Academy and embracing the sincerity and detailed naturalism they perceived in Italian art before Raphael. Though the original Brotherhood had largely dissolved by the time Morris met Rossetti, Rossetti's artistic vision and magnetic personality profoundly influenced Morris and Burne-Jones.

The Pre-Raphaelite Influence and Early Artistic Endeavours

The Pre-Raphaelite ethos, with its emphasis on truth to nature, intricate detail, literary and historical subjects (especially medieval and Arthurian legends), and a certain romantic intensity, captivated Morris. He briefly apprenticed himself to the Gothic Revival architect George Edmund Street in 1856, where he met Philip Webb, another future collaborator. However, under Rossetti's persuasion, Morris soon abandoned architecture for painting, sharing a studio with Burne-Jones in London.

Morris's foray into painting was relatively short-lived. His most notable easel painting, "La Belle Iseult" (1858, also known as "Queen Guinevere"), features Jane Burden, whom he met in Oxford and would marry in 1859. While the painting demonstrates Pre-Raphaelite characteristics in its medieval theme and rich detail, Morris reportedly struggled with figure painting and grew frustrated. His true talents lay elsewhere, in pattern design and the decorative arts.

A significant collaborative project during this period was the decoration of the Oxford Union debating hall in 1857. Rossetti enlisted Morris, Burne-Jones, and other young artists like Arthur Hughes, Val Prinsep, and John Roddam Spencer Stanhope to paint murals based on Arthurian legends. Morris's contribution depicted scenes from the tale of Sir Tristram. Though technically flawed and quickly deteriorating due to the artists' inexperience with fresco techniques, the Oxford Union murals were a formative experience, fostering a spirit of collaborative artistic endeavour that would be central to Morris's later ventures.

Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co.: "The Firm"

The desire to create beautiful, well-made objects for everyday life, and the frustration with the poor quality and over-ornamentation of commercially available decorative arts, led Morris to a groundbreaking decision. In 1861, he co-founded Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co., often referred to as "The Firm." The partners included Morris, Burne-Jones, Rossetti, Philip Webb, Ford Madox Brown (another painter associated with the Pre-Raphaelites), Charles Faulkner (an Oxford friend and mathematician), and Peter Paul Marshall (a surveyor and engineer).

The Firm aimed to undertake all manner of decoration, offering a holistic approach to interior design. Their prospectus declared their intention to produce furniture, stained glass, metalwork, jewellery, embroidery, and murals. This was a radical departure from the prevailing specialisation in the decorative arts. They sought to revive traditional craft techniques and elevate the status of decorative art to that of fine art, a core tenet of what would become the Arts and Crafts Movement.

Their early commissions included stained glass for churches, such as All Saints' Church in Selsley, Gloucestershire, and the decoration of St. James's Palace. The Firm's stand at the 1862 International Exhibition in London garnered significant attention, showcasing their distinctive style, which drew heavily on medieval precedents and natural forms, contrasting sharply with the prevailing High Victorian taste. Artists like Simeon Solomon and Arthur Hughes also contributed designs to The Firm in its early days.

The Red House: A Manifesto in Brick and Mortar

Before the formal establishment of The Firm, Morris had already embarked on a project that embodied his burgeoning design philosophy: the Red House. Built in Bexleyheath, Kent, between 1859 and 1860, it was designed by Philip Webb for Morris and his new wife, Jane. The Red House is considered a seminal building in the history of domestic architecture and a precursor to the Arts and Crafts style.

Rejecting the fashionable Italianate stucco villas of the period, Webb and Morris opted for an honest use of red brick, an L-shaped plan, and an informal, picturesque asymmetry inspired by medieval vernacular architecture. The interior was conceived as a collaborative artistic project, with Morris, Jane, Burne-Jones, Rossetti, and others contributing to its decoration. They painted murals, designed stained glass, embroidered hangings, and created custom furniture.

The Red House was intended to be a "Palace of Art" where life and art were seamlessly integrated. It was here that Morris first experimented extensively with wallpaper and textile design, unable to find existing products that met his aesthetic standards. The experience of furnishing and decorating the Red House directly fuelled the creation of Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co., as it highlighted the need for well-designed, handcrafted alternatives to mass-produced goods.

Master of Pattern: Textiles and Wallpapers

While Morris's contributions to The Firm were diverse, he became particularly renowned for his two-dimensional patterns for wallpapers and textiles. His first wallpaper design, "Trellis" (1862), inspired by the rose trellises at the Red House, with birds drawn by Philip Webb, set the tone for his future work. It was followed by "Daisy" (1864) and "Fruit" (or "Pomegranate") (1864), all characterised by their stylised naturalism and flat, repeating patterns.

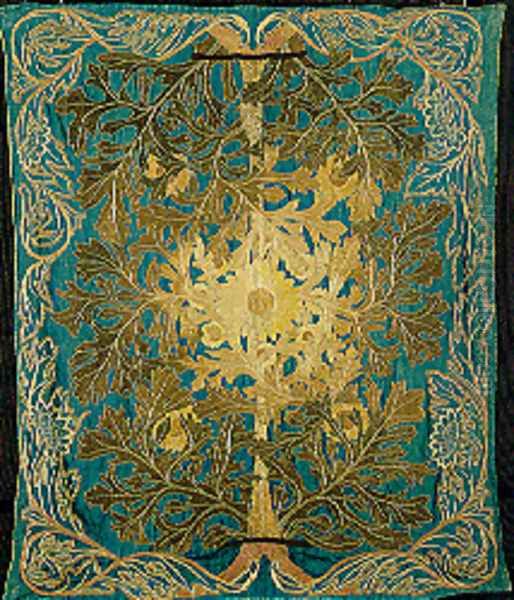

Morris's designs drew inspiration from historical sources, including medieval illuminated manuscripts, tapestries, and early printed herbals, as well as directly from nature observed in gardens and hedgerows. He meticulously studied the structure of plants, translating their organic forms into intricate, rhythmic, and harmonious patterns. Popular designs include "Acanthus" (1875), "Marigold" (1875), "Pimpernel" (1876), "Chrysanthemum" (1877), and the iconic "Strawberry Thief" (1883), a complex block-printed cotton inspired by thrushes stealing fruit in his garden at Kelmscott Manor.

He was deeply involved in the production process, reviving old techniques like woodblock printing for wallpapers and indigo discharge dyeing for textiles. He established his own workshops at Merton Abbey Mills in 1881 to ensure quality control and ethical labour practices. His textiles included printed cottons, woven woollens (often used for upholstery and curtains), silk damasks, and elaborate hand-knotted Hammersmith carpets and Arras tapestries, the latter often featuring figural designs by Burne-Jones with backgrounds and floral details by Morris himself or his chief assistant, John Henry Dearle. Dearle became a highly accomplished designer in his own right, continuing Morris's style after his death.

Literary Achievements: Poet and Romancer

Alongside his burgeoning design career, William Morris was a prolific and celebrated writer. His first published work was "The Defence of Guenevere, and Other Poems" (1858). These early poems, influenced by Rossetti and medieval romances, were praised for their vivid imagery and dramatic intensity, though they did not achieve widespread popularity at the time.

His literary reputation soared with the publication of "The Life and Death of Jason" (1867), a narrative poem retelling the Greek myth, and "The Earthly Paradise" (1868-1870), a monumental collection of narrative poems. "The Earthly Paradise" framed a series of classical and medieval tales, supposedly told by Norse wanderers who had set out to find a mythical land of eternal life. These works, with their melodic verse and escapist themes, resonated with Victorian readers and established Morris as a major poet of his generation, alongside figures like Alfred, Lord Tennyson, and Robert Browning.

Morris also developed a deep interest in Icelandic sagas, learning Old Norse and travelling to Iceland in 1871 and 1873. These journeys had a profound impact on him. He collaborated with Eiríkr Magnússon on translations of numerous sagas, including the "Volsunga Saga." His epic poem "Sigurd the Volsung and the Fall of the Niblungs" (1876), based on this saga, was considered by Morris himself to be his finest poetic achievement.

In his later years, Morris turned to prose romances, pioneering a genre that would significantly influence later fantasy writers like J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis. Works such as "The House of the Wolfings" (1889), "The Roots of the Mountains" (1889), "The Story of the Glittering Plain" (1891), "The Wood Beyond the World" (1894), and "The Well at the World's End" (1896) are set in fantastical medieval-esque worlds, exploring themes of heroism, love, and the quest for an ideal society.

The Kelmscott Press: The Book Beautiful

Morris's passion for medieval craftsmanship extended to the art of the book. Dismayed by the poor quality of typography and book production in his time, he founded the Kelmscott Press in 1891 in Hammersmith, London. His aim was to revive the aesthetics and craft principles of early printers like Nicolas Jenson and Erhard Ratdolt from the 15th century, producing books that were beautiful objects in themselves.

The Press used custom-designed typefaces created by Morris – "Golden," "Troy," and "Chaucer" – inspired by incunabula. Paper was handmade, and ink was specially formulated. The books featured intricate woodcut borders, initials, and illustrations, many designed by Morris himself or by Edward Burne-Jones, whose illustrations for the Kelmscott edition of "The Works of Geoffrey Chaucer" are particularly renowned. Other artists like Walter Crane and Charles March Gere also contributed.

The Kelmscott Press produced 53 titles in 66 volumes over seven years. Its magnum opus, the "Kelmscott Chaucer" (1896), is widely regarded as one of the most beautiful books ever printed and a landmark in the history of book design. The Press had a profound influence on the private press movement and raised standards of book production generally, inspiring printers and designers such as T.J. Cobden-Sanderson of the Doves Press, C.R. Ashbee of the Essex House Press, and later, American figures like Frederic Goudy and Bruce Rogers.

Socialism and Political Activism

William Morris's artistic and literary pursuits were increasingly intertwined with his evolving social and political convictions. His critique of industrial society, initially aesthetic and rooted in Ruskin's ideas, developed into a committed socialist stance. He believed that capitalism was responsible for the ugliness of modern life, the exploitation of workers, and the destruction of both art and nature.

In 1883, Morris joined the Democratic Federation, Britain's first socialist organisation, later renamed the Social Democratic Federation (SDF), led by H.M. Hyndman. He became a tireless propagandist for the socialist cause, lecturing extensively across the country, writing articles and pamphlets, and participating in street demonstrations. His wealth was generously used to support the movement.

Disagreements over strategy and ideology led Morris and others, including Eleanor Marx (Karl Marx's daughter) and Edward Aveling, to split from the SDF in late 1884 and form the Socialist League. Morris became the editor of its journal, "Commonweal," to which he contributed numerous articles, poems, and his utopian romance, "News from Nowhere" (serialised 1890). "News from Nowhere" paints a picture of an idealised future communist society in Britain, where work is pleasurable, nature is revered, and coercive government has withered away.

Morris's socialist activities were not without personal cost. He was arrested during a demonstration for free speech at Dodson Street in September 1885, though the charges were dismissed. He witnessed the "Bloody Sunday" protest in Trafalgar Square in 1887, where police violently suppressed a demonstration. Internal divisions within the Socialist League, particularly the growing influence of anarchists, led Morris to resign his editorship of "Commonweal" in 1890 and eventually to withdraw from active frontline politics, though he remained a committed socialist until his death. His political associates included figures like Andreas Scheu, Ernest Belfort Bax, and the future Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald in his early socialist days.

Personal Life, Friendships, and Kelmscott Manor

In 1859, William Morris married Jane Burden. Jane, with her striking, unconventional beauty, became a muse for both Morris and Dante Gabriel Rossetti. The Morris marriage was complex. While there was affection, Jane developed an intensely close and likely romantic relationship with Rossetti, particularly during the early 1870s when Rossetti co-tenanted Kelmscott Manor with the Morrises. Morris appears to have tolerated this situation, perhaps out of a belief in personal freedom or a desire to avoid scandal. The couple had two daughters, Jane Alice (Jenny) and Mary (May). Jenny suffered from epilepsy, which caused Morris great distress. May Morris became an important embroiderer and editor of her father's collected works.

Kelmscott Manor, a 17th-century limestone farmhouse in the Cotswolds, became Morris's beloved country retreat from 1871. Its idyllic setting and traditional architecture deeply resonated with his aesthetic and social ideals, providing inspiration for many of his designs and writings.

Beyond his immediate family and The Firm collaborators, Morris maintained a wide circle of friends and acquaintances, including the poet Algernon Charles Swinburne, the artist George Frederic Watts, and the writer and activist Annie Besant. His robust personality, sometimes prone to fits of temper but fundamentally generous and idealistic, made him a commanding presence.

The Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings (SPAB)

Another significant aspect of Morris's activism was his commitment to architectural conservation. Appalled by the destructive "restoration" practices of many Victorian architects, particularly Sir George Gilbert Scott, who often sought to impose a conjectural and often inaccurate "ideal" medieval state on old buildings, Morris founded the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings (SPAB) in 1877.

Known affectionately as "Anti-Scrape," SPAB advocated for a conservative approach to repair, emphasising the preservation of a building's authentic historical fabric rather than its speculative reconstruction. The Society's manifesto, penned by Morris, argued for "Protection in the place of Restoration." SPAB attracted many influential supporters, including Thomas Carlyle, John Ruskin, and Philip Webb, and played a crucial role in shaping modern conservation philosophy and practice in Britain and beyond.

Later Years and Enduring Legacy

In its later years, The Firm was reorganised in 1875 as Morris & Co., with Morris as the sole proprietor. It continued to flourish, producing high-quality decorative arts that defined the Arts and Crafts aesthetic. John Henry Dearle became the company's chief designer and art director after Morris's death, capably continuing its distinctive style well into the 20th century.

William Morris's prodigious energy eventually took its toll. His health declined in the 1890s, exacerbated by diabetes and gout. He died at Kelmscott House, his London home in Hammersmith, on October 3, 1896, at the age of 62. His physician famously remarked that his illness was "simply being William Morris, and having done more work than most ten men."

The legacy of William Morris is vast and multifaceted. As a designer, he spearheaded the Arts and Crafts Movement, which had a profound international impact, influencing Art Nouveau, the Vienna Secession (Gustav Klimt, Josef Hoffmann), the Deutscher Werkbund, and the American Arts and Crafts movement (Gustav Stickley, Greene and Greene). His emphasis on craftsmanship, the honest use of materials, and design inspired by nature continues to inform design practice. His patterns remain immensely popular and are still reproduced today.

As a writer, his poetry was highly regarded in his lifetime, and his prose romances are now seen as foundational texts in the development of modern fantasy literature. As a social thinker and activist, his critique of capitalism and his vision of a socialist utopia inspired generations of reformers and radicals. His advocacy for environmentalism and architectural preservation was prescient.

Exhibitions of his work continue to draw large audiences worldwide. For instance, the exhibition "Beauty's Awakening: William Morris and the British Arts & Crafts Movement," featuring items from the Victoria and Albert Museum, was scheduled for Shanghai in late 2024 to 2025. "L'Art dans tout" (Art in Everything) at La Piscine museum in Roubaix, France, in 2024, also showcased his diverse output. The William Morris Gallery in Walthamstow, his childhood home, is a dedicated museum celebrating his life and work, hosting exhibitions like "Radical Landscapes."

Conclusion: A Visionary for All Time

William Morris was more than just an artist or a writer; he was a visionary who sought to transform society through art and action. He believed that art should be "by the people and for the people," a source of joy in everyday life and a product of fulfilling labour. His rejection of industrial ugliness, his championing of handcraft, his love for the natural world, and his passionate advocacy for social justice remain profoundly relevant. In an age still grappling with issues of mass production, environmental degradation, and social inequality, William Morris's life and work offer enduring inspiration and a compelling call for a more beautiful, equitable, and humane world. His influence can be seen in the work of countless artists and designers who followed, from Charles Rennie Mackintosh in Scotland to Frank Lloyd Wright in America, all of whom, in various ways, absorbed the spirit of the Arts and Crafts ideals he so powerfully embodied.