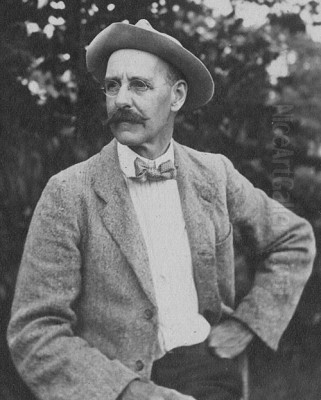

William Stedman Robinson (1861-1945) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the annals of American art, particularly within the Impressionist movement that flourished at the turn of the twentieth century. Born in East Gloucester, Massachusetts, a region renowned for its maritime heritage and picturesque scenery, Robinson's artistic sensibilities were shaped from an early age by the rugged New England coastline and the ever-changing Atlantic. His long and dedicated career saw him evolve from a painter influenced by the tonalism of the Barbizon School to a leading exponent of American Impressionism, particularly associated with the famed Old Lyme Art Colony in Connecticut. This article will delve into the life, artistic development, key works, and lasting legacy of William S. Robinson, placing him within the broader context of his contemporaries and the artistic currents of his time.

Early Life and Artistic Awakenings

William S. Robinson was born on September 15, 1861, in East Gloucester, Massachusetts. The son of a fisherman, his early life was intrinsically linked to the sea, an element that would recur thematically in his later artistic output. The maritime environment of Cape Ann, with its bustling harbors, dramatic cliffs, and the unique quality of its light, undoubtedly provided a rich visual tapestry for the young Robinson. This early immersion in a landscape so deeply intertwined with American identity and artistic tradition laid a foundational layer for his future pursuits.

His formal artistic training began locally, at the Massachusetts Normal Art School in Boston (now the Massachusetts College of Art and Design). This institution, founded to provide drawing teachers for public schools and to train professional artists and designers, would have equipped him with fundamental skills in draftsmanship and composition. During the early 1880s, Robinson began his teaching career in the Boston area, a profession he would return to at various points in his life, demonstrating a commitment to nurturing artistic talent in others alongside his own creative endeavors.

His pedagogical journey soon took him further afield. From 1885 to 1889, Robinson held a teaching position at the Maryland Institute College of Art in Baltimore (then known as the Maryland Institute for the Promotion of the Mechanic Arts, with its art school sometimes referred to as the Mary Washington Art School during certain periods or within specific departments). This period of teaching likely solidified his own understanding of artistic principles and provided him with a steady, albeit modest, income as he continued to develop his painterly voice.

The Parisian Sojourn and Barbizon Influences

Like many ambitious American artists of his generation, William S. Robinson recognized the imperative of European study to refine his technique and broaden his artistic horizons. In the early 1890s, he embarked for Paris, the undisputed epicenter of the art world at the time. There, he enrolled at the Académie Julian, a renowned private art school that attracted students from across the globe, including a significant contingent of Americans. The Académie Julian offered an alternative to the more rigid École des Beaux-Arts, providing opportunities for artists to work from live models and receive critiques from established academic painters. Among the notable instructors at the Académie Julian during various periods were figures like William-Adolphe Bouguereau, Tony Robert-Fleury, Jules Joseph Lefebvre, and Benjamin Constant, whose teachings, while traditional, provided a strong grounding.

During his time in Paris, Robinson was particularly drawn to the aesthetics of the French Barbizon School. Painters such as Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, Jean-François Millet, Théodore Rousseau, and Charles-François Daubigny had, in the mid-19th century, championed landscape painting that emphasized realism, tonal harmony, and an intimate, often poetic, depiction of nature. They worked directly from nature in the Forest of Fontainebleau, capturing the fleeting effects of light and atmosphere. This approach resonated deeply with Robinson, and its influence is palpable in his earlier works, which often exhibit a gentle, lyrical quality, a muted palette, and a focus on mood and atmosphere over precise detail. He also reportedly studied with Henri Harpignies, a later Barbizon-associated landscape painter known for his structured compositions and clear light.

Upon his return to the United States, Robinson began to establish his reputation. He started exhibiting his work, notably in New York and Philadelphia, major art centers where he could gain visibility and connect with patrons and fellow artists. His first submission to the prestigious National Academy of Design in New York occurred in 1891, marking his entry into the national art scene. Despite facing the economic challenges common to many artists, he persevered, continuing to paint and teach.

The Old Lyme Art Colony: A Crucible of American Impressionism

A transformative chapter in William S. Robinson's career began around 1905 when he first visited Old Lyme, Connecticut. This picturesque village, situated at the mouth of the Connecticut River, had become the home of the Old Lyme Art Colony, one of America's most significant centers of Impressionist painting. The colony was largely centered around the Florence Griswold Boarding House, a gracious late-Georgian mansion run by Miss Florence Griswold, who became a beloved patron and supporter of the artists.

The colony had initially been established under the influence of Henry Ward Ranger, an artist whose Tonalist style, inspired by the Barbizon School, first attracted artists to Old Lyme. Ranger's evocative, moody landscapes set the initial artistic tone. However, the arrival of Childe Hassam in 1903 marked a decisive shift towards Impressionism. Hassam, one of America's foremost Impressionists, brought with him a brighter palette, a focus on capturing the fleeting effects of light and color, and broken brushwork characteristic of the French Impressionists like Claude Monet, whose work Hassam had encountered directly in Paris.

Robinson found himself in a vibrant and stimulating artistic milieu. He became a regular summer visitor and eventually a permanent resident of the Florence Griswold House, moving in officially in 1921 and even building his own studio on the property. He continued to live and work there even after Miss Florence's passing in 1937, a testament to his deep connection to the place and its artistic community.

At Old Lyme, Robinson's style underwent a noticeable evolution. While retaining some of the poetic sensibility of his earlier Barbizon-influenced work, he embraced the brighter palette and more broken brushwork of Impressionism. He was undoubtedly influenced by Childe Hassam, as well as other prominent Impressionists who frequented Old Lyme, such as Willard Metcalf, known for his exquisite depictions of the New England landscape; Walter Griffin, who also spent time in France; Frank DuMond, an influential teacher; Wilson Irvine, known for his innovative "aqua-print" technique and prismatic palette; and Lewis Cohen. The camaraderie and friendly artistic rivalry within the colony fostered experimentation and growth. Artists would often paint en plein air, capturing the local scenery – the marshes, rivers, gardens, and colonial architecture – under varying conditions of light and season.

Robinson became particularly known for his depictions of the laurel, Connecticut's state flower, which bloomed profusely in the region. His paintings of laurel in sun-dappled woodlands, often featuring vibrant pinks and whites against lush greens, became some of his most sought-after works. Titles such as "Laurel" and "The Old Sluice Way, Old Lyme" are indicative of his focus on the local scenery. He also painted coastal scenes, drawing on his East Gloucester roots, with works like "Monhegan Headland" showcasing his ability to capture the atmospheric conditions of the New England coast.

Artistic Style and Thematic Focus

William S. Robinson's mature style is best characterized as American Impressionism, though it retained a distinctive lyrical quality that perhaps harked back to his Barbizon affinities. Unlike some of his contemporaries who adopted a more scientific or purely optical approach to Impressionism, Robinson's work often conveyed a deep emotional connection to the landscape.

His palette became significantly lighter and more vibrant during his Old Lyme period. He employed broken brushwork to capture the shimmer of light on water, the texture of foliage, and the ephemeral quality of atmospheric conditions. His understanding of color was sophisticated, allowing him to create harmonious compositions that were both visually stimulating and emotionally resonant. He was adept at capturing the distinct qualities of New England light, from the crisp clarity of a summer morning to the soft haze of an autumn afternoon.

Robinson's primary subject matter was the New England landscape. He painted its rolling hills, meandering rivers, colonial homesteads, and, of course, its distinctive flora, especially the mountain laurel. His seascapes and coastal views, while perhaps less numerous than his inland landscapes from the Old Lyme period, were also an important part of his oeuvre, reflecting his lifelong connection to the maritime world. He often depicted scenes from Monhegan Island, Maine, a rugged and inspiring location favored by many American artists, including Rockwell Kent and Edward Hopper.

His compositions were generally well-structured, demonstrating the solid academic training he had received. However, this structure served as a scaffold for his more expressive handling of color and light. There is a sense of tranquility and order in many of his paintings, a celebration of the pastoral beauty of the American countryside. He was less concerned with the social commentary or urban scenes that interested some other American artists of the period, like those of the Ashcan School (e.g., Robert Henri, John Sloan), preferring instead to focus on the enduring beauty of the natural world.

Professional Recognition and Affiliations

Throughout his career, William S. Robinson achieved considerable professional recognition. He was an active participant in the art world, exhibiting widely and involving himself in various artistic organizations. His dedication to the medium of watercolor was particularly notable, and he served as President of the American Watercolor Society, a prestigious role that underscored his mastery of this challenging medium. He was also a member of the Salmagundi Club and the Lotos Club, both important social and professional organizations for artists in New York.

Furthermore, Robinson was elected an Associate of the National Academy of Design (ANA) in 1911 and a full National Academician (NA) in 1914. Membership in the National Academy was, and remains, a significant honor, signifying recognition by one's peers at the highest level. He also served on committees for the Academy, contributing to its governance and activities.

His works were frequently included in major national and international exhibitions, where they garnered awards and critical acclaim. He received a bronze medal at the Paris Exposition Universelle of 1900, an Honorable Mention at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo in 1901, a silver medal at the St. Louis Louisiana Purchase Exposition in 1904, and a gold medal at the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco in 1915. These accolades demonstrate his standing not only within American art circles but also on the international stage.

His paintings were acquired by several prominent museums during his lifetime and posthumously, including the Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh, the Dallas Museum of Art, the Cleveland Museum of Art, the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C., and the Florence Griswold Museum in Old Lyme, which holds a significant collection of works by artists of the Old Lyme Art Colony.

Later Years and Continued Dedication

William S. Robinson remained deeply committed to his art throughout his life. He was known for his quiet and dedicated personality. Unlike some of the more flamboyant figures in the art world, Robinson was described as a gentle and somewhat reserved man, entirely devoted to his painting. He never married, and his life revolved around his artistic pursuits and his close-knit community of fellow artists, particularly in Old Lyme.

In 1937, a significant change occurred in his life with the death of Florence Griswold. Though he continued to live and work at the Griswold House, the passing of its beloved matriarch marked the end of an era for the Old Lyme Art Colony. Around this time, or shortly thereafter, Robinson began spending winters in Biloxi, Mississippi. This move to a different climate and landscape offered new subjects, and he painted scenes of the Mississippi Gulf Coast. However, his heart seemingly remained in New England, as he continued to paint Connecticut landscapes, often from memory or earlier sketches, even while in the South.

Some observers note a subtle shift in his later work, with perhaps a greater emphasis on realism and precise detail, though still imbued with his characteristic sensitivity to light and atmosphere. His dedication to capturing the essence of the American landscape remained unwavering until his death. William S. Robinson passed away in Biloxi, Mississippi, on January 11, 1945, at the age of 83.

Legacy and Enduring Influence

William S. Robinson's legacy is that of a dedicated and talented painter who made significant contributions to American Impressionism. He was a key figure in the Old Lyme Art Colony, one of the most important centers for the development of this style in the United States. His work exemplifies the American adaptation of French Impressionist principles, filtered through a distinctly national sensibility and a deep love for the New England landscape.

His paintings are admired for their lyrical beauty, their skillful handling of light and color, and their evocative portrayal of place. While he may not have achieved the same level of widespread fame as some of his contemporaries like Childe Hassam, Mary Cassatt, or John Singer Sargent, his work is highly regarded by collectors and scholars of American art. His paintings continue to be exhibited and are found in numerous public and private collections.

The Florence Griswold Museum in Old Lyme stands as a primary repository of his work and a testament to the artistic community of which he was such an integral part. The museum not only preserves his paintings but also the environment in which he and his fellow artists worked, offering invaluable insights into the life and times of the American Impressionists.

Robinson's influence can also be seen in his role as a teacher. Through his instructional work at various institutions and his informal interactions with younger artists, he helped to perpetuate the traditions of landscape painting and Impressionist technique. His commitment to organizations like the American Watercolor Society and the National Academy of Design also speaks to his dedication to the broader artistic community.

In the context of American art history, William S. Robinson is remembered as an artist who beautifully captured the spirit of the New England landscape. He, along with other American Impressionists such as John Henry Twachtman, J. Alden Weir (both associated with the Cos Cob Art Colony, another Connecticut Impressionist hub), Theodore Robinson (no relation, but an early American adopter of Impressionism through his Giverny experiences with Monet), and Boston School painters like Frank Weston Benson and Edmund Tarbell, helped to define a distinctly American vision of Impressionism. His work stands as a lasting tribute to the beauty of the American scene and the enduring appeal of painting light and nature.

Conclusion

William S. Robinson's artistic journey from the fishing wharves of East Gloucester to the hallowed halls of the National Academy of Design, and most notably to the idyllic landscapes of Old Lyme, Connecticut, charts the course of a dedicated and sensitive painter. His adoption and adaptation of Impressionist techniques, combined with a lyrical quality rooted in Barbizon aesthetics, resulted in a body of work that celebrates the nuanced beauty of the American landscape. As a respected teacher, an active member of the artistic community, and a pivotal figure in the Old Lyme Art Colony, Robinson left an indelible mark on American art. His paintings continue to resonate with viewers today, offering a timeless vision of light, color, and the serene poetry of nature as seen through the eyes of a master of American Impressionism.