Michelangelo Merisi, known to the world as Caravaggio (1571-1610), stands as one of the most influential, innovative, and controversial figures in the history of Western art. Born in Milan but named after the nearby town of Caravaggio where his family originated, he fundamentally reshaped painting in Rome during the late 16th and early 17th centuries. His work ushered in the Baroque era with a powerful, dramatic realism and a revolutionary use of light and shadow that left an indelible mark on generations of artists across Europe. His life, as tumultuous and dramatic as his canvases, adds another layer to the enduring fascination with this Italian master.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Michelangelo Merisi was born likely on September 29, 1571, the feast day of the Archangel Michael, hence his first name. His father, Fermo Merisi, was a household administrator and architect-decorator for Francesco Sforza I da Caravaggio, the Marchese of Caravaggio. His mother, Lucia Aratori, came from a propertied local family. The plague that struck Milan in 1576 prompted the family to move to the town of Caravaggio to escape the epidemic, but both his father and grandfather died there in 1577. The young Michelangelo grew up in Caravaggio but returned to Milan for his artistic training.

In 1584, at the age of thirteen, Caravaggio was apprenticed for four years to the Milanese painter Simone Peterzano. Peterzano, himself a pupil of the great Venetian master Titian, was considered a competent, if somewhat conventional, painter working in the late Mannerist style. This apprenticeship provided Caravaggio with a solid grounding in the fundamentals of painting. More importantly, it exposed him to the Lombard tradition of realism and the Venetian emphasis on color and light, influences that would prove crucial to his later development. Artists like Giovanni Gerolamo Savoldo and Moretto da Brescia, active in the Lombard region, had already cultivated a style marked by naturalistic detail and dramatic lighting, prefiguring Caravaggio's own path.

Roman Breakthrough and Stylistic Innovation

Around 1592, Caravaggio left Milan and, after possibly stopping briefly in Venice, arrived in Rome, the vibrant artistic center of Italy. His early years in the city were marked by poverty and struggle. He initially found work producing paintings on spec and doing piecework for other, more established artists, such as the Cavaliere d'Arpino (Giuseppe Cesari), for whom he reportedly painted fruit and flowers in workshop productions. During this period, he suffered from illness and lack of funds, experiences reflected in early works like the Sick Bacchus (c. 1593-94), believed by some to be a self-portrait during his convalescence.

Caravaggio's fortunes began to change when his talent caught the eye of influential patrons. Cardinal Francesco Maria del Monte, a sophisticated connoisseur and diplomat, became one of his most important early supporters around 1595. Del Monte not only purchased several of Caravaggio's works but also provided him with lodging, board, and a stipend in his Palazzo Madama. This patronage was crucial, offering Caravaggio stability and access to Rome's elite cultural circles. Works created during this period, such as The Musicians (c. 1595-96), The Lute Player (c. 1596), and Bacchus (c. 1596-97), often feature sensuous youths in intimate settings, showcasing his developing mastery of realism and light.

It was during these years in Rome that Caravaggio forged his signature style, characterized by an intense and dramatic use of chiaroscuro – the contrast between light and dark. He pushed this technique to an extreme, developing what became known as tenebrism, where darkness dominates the canvas, pierced by shafts of brilliant, often theatrical light that illuminates the key figures and action. This wasn't merely a stylistic device; it created profound psychological depth, heightened emotional impact, and focused the narrative with unprecedented intensity. His commitment to realism was equally radical, using ordinary people, sometimes drawn from the streets of Rome, as models for saints and holy figures, depicting them with unflinching naturalism, complete with dirty feet and wrinkled brows.

Masterworks and Religious Commissions

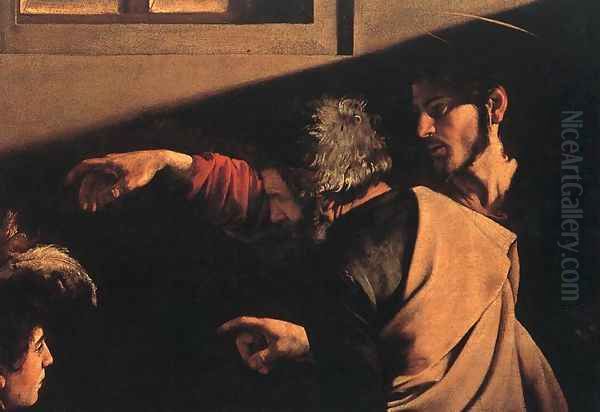

Caravaggio's breakthrough into the lucrative world of public commissions came in 1599-1600 when he was contracted to decorate the Contarelli Chapel in the church of San Luigi dei Francesi in Rome. His two large canvases for the side walls, The Calling of Saint Matthew and The Martyrdom of Saint Matthew, caused a sensation. The Calling depicts the moment Christ summons Matthew, a tax collector, to follow him. Caravaggio sets the scene in what appears to be a contemporary Roman tavern, with figures in 17th-century dress. A beam of divine light cuts across the darkness, illuminating Matthew's face as Christ points towards him, creating a moment of intense spiritual drama grounded in everyday reality.

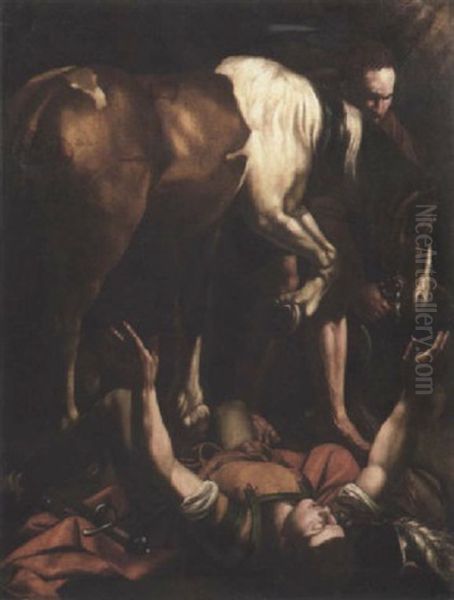

These works cemented Caravaggio's reputation as a leading painter in Rome, leading to further prestigious commissions. For the Cerasi Chapel in Santa Maria del Popolo (1600-1601), he painted The Conversion of Saint Paul and The Crucifixion of Saint Peter. Again, his approach was revolutionary. In the Conversion, Paul lies stunned beneath his horse, bathed in divine light, the event depicted with startling immediacy and physical presence. The Crucifixion of Peter shows the aged apostle being hoisted upside down on the cross by straining laborers, emphasizing the brutal physicality and humility of martyrdom.

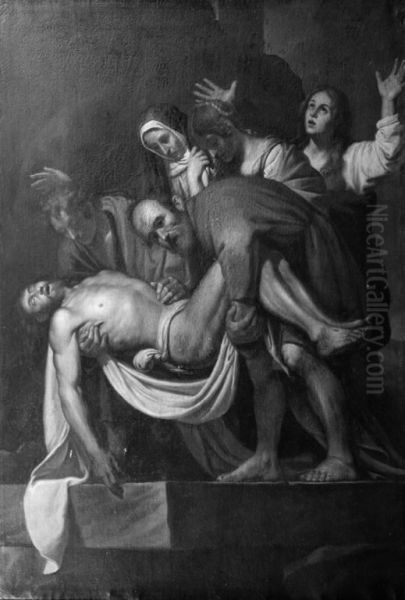

Not all of Caravaggio's religious works were readily accepted. His first version of Saint Matthew and the Angel for the Contarelli Chapel altarpiece was rejected, possibly because the saint was depicted as a clumsy peasant with bare, dirty feet, guided by an overly familiar angel. His Death of the Virgin (1601-1606), commissioned for Santa Maria della Scala in Trastevere, was also refused by the Carmelite friars. They reportedly found the realistic depiction of the Virgin Mary – modeled, according to rumor, on a drowned prostitute – and the raw grief of the apostles lacking in theological decorum. The painting was later purchased by the Duke of Mantua on the advice of Peter Paul Rubens, demonstrating its appreciation among fellow artists. Other major works from this period include The Entombment of Christ (1603-04) and the Madonna di Loreto (1604-06).

A Life of Turmoil and Exile

Caravaggio's artistic triumphs unfolded against a backdrop of personal chaos. He possessed a notoriously volatile temper and a penchant for violence. His name appeared frequently in police records for brawls, carrying weapons without a license, and insulting city guards. He was involved in numerous altercations, including a documented libel suit brought against him by the painter Giovanni Baglione in 1603, which also involved fellow artists Orazio Gentileschi, Onorio Longhi, and Filippo Trisegni. Caravaggio's deposition provides rare insight into his views on art and his contemporaries.

His turbulent life reached a crisis point on May 29, 1606. Following a dispute over a tennis match score, possibly exacerbated by gambling debts or a quarrel over a woman, Caravaggio engaged in a sword fight with Ranuccio Tomassoni, a young man from a respectable family. Caravaggio wounded Tomassoni fatally and was himself injured. Facing a capital sentence for murder, Caravaggio fled Rome.

This marked the beginning of a period of exile that would last for the rest of his short life. He first found refuge in Naples, which was then under Spanish rule and outside the jurisdiction of Rome. Despite being a fugitive, his fame preceded him, and he quickly received important commissions, painting works like the Seven Works of Mercy (1607) and The Flagellation of Christ (c. 1607). His Neapolitan works often exhibit even deeper shadows and heightened emotional intensity.

From Naples, Caravaggio traveled to Malta in 1607, likely seeking the patronage of the Knights of Malta and hoping their influence could help secure a papal pardon. He was inducted into the Order as a Knight of Grace in 1608 and painted several significant works, including the monumental Beheading of Saint John the Baptist (1608), his only signed work, for St. John's Co-Cathedral in Valletta. However, his violent nature soon resurfaced. Following another brawl, possibly involving a senior knight, he was imprisoned and subsequently expelled from the Order "as a foul and rotten member" in December 1608.

He escaped prison and fled to Sicily, moving between Syracuse, Messina, and Palermo from late 1608 to 1609. Here too, despite his precarious situation, he continued to paint powerful, often somber works like The Burial of Saint Lucy (1608) and The Raising of Lazarus (1609). These late works are characterized by vast, empty spaces dwarfing the figures, conveying a sense of tragedy and human vulnerability.

Final Years and Mysterious Death

In late 1609, Caravaggio returned to Naples, perhaps believing it safer or closer to Rome as negotiations for his pardon progressed. His powerful connections, including Cardinal Scipione Borghese, nephew of Pope Paul V, were working on his behalf. However, danger still followed him. In Naples, he was ambushed and severely wounded in the face outside a tavern, an attack possibly orchestrated by enemies from Malta or related to the Tomassoni affair. Rumors even circulated in Rome that he had died.

Recovering from his injuries, Caravaggio continued to paint, producing works like David with the Head of Goliath (c. 1609-10), where the severed head is believed to be a self-portrait, and The Martyrdom of Saint Ursula (1610), one of his last documented paintings. By the summer of 1610, news of an imminent papal pardon seemed likely. Caravaggio set sail from Naples for Rome, carrying several paintings intended as gifts for Cardinal Borghese.

The circumstances surrounding his death remain murky. According to early accounts, he was mistakenly arrested and briefly imprisoned in Palo, north of Rome. Upon his release, he discovered the ship carrying his paintings had sailed on. Frantically trying to recover his possessions, he traveled south along the coast under the scorching summer sun and collapsed at Porto Ercole, a Spanish garrison town. He died there a few days later, on July 18, 1610, likely from fever, possibly aggravated by his previous wounds or underlying health issues like syphilis or brucellosis. Recent studies analyzing his remains have also suggested lead poisoning from his paints as a contributing factor. He died just days before his pardon was officially announced.

Caravaggio's Artistic Style: Realism and Tenebrism

Caravaggio's style was revolutionary for its time, marking a significant departure from the idealized forms of Renaissance and Mannerist painting. His core tenets were realism and dramatic intensity, achieved primarily through his masterful use of light and shadow (chiaroscuro) and his insistence on painting from life.

His realism was uncompromising. He selected models from the common people – peasants, courtesans, street urchins – and depicted them with startling fidelity, capturing their individual features, ragged clothes, and emotional states. When painting religious scenes, he placed biblical figures in contemporary settings and attire, making sacred events feel immediate and relatable. This naturalism extended to depicting physical exertion, pain, and death with unflinching honesty, which sometimes shocked patrons accustomed to more idealized representations.

Tenebrism was Caravaggio's most distinctive stylistic signature. He plunged large areas of his canvases into deep shadow, using darkness not just as background but as an active element that creates mystery, suspense, and focus. From this darkness, figures emerge dramatically into pools of harsh, often raking light, typically from a single, unseen source. This intense light models forms with sculptural solidity, highlights crucial details and gestures, and heightens the emotional and psychological drama of the scene. It functions as both a physical and symbolic element, often representing divine intervention or revelation.

His compositions were often tightly cropped, bringing the figures close to the picture plane and immersing the viewer directly in the scene. He favored moments of peak action or intense psychological revelation, capturing the immediacy of the event. Unlike many Renaissance predecessors who relied on extensive preparatory drawings, Caravaggio reportedly worked directly onto the canvas, making incisions in the ground layer to outline his compositions, contributing to the sense of spontaneity and raw energy in his work.

Contemporaries and Artistic Milieu

Caravaggio worked during a period of intense artistic activity in Rome, fueled by the Counter-Reformation Church's desire for art that was direct, emotionally engaging, and theologically clear. While his style was unique, he was aware of and responded to the artistic currents around him. His Lombard training under Peterzano connected him to the naturalistic traditions of Northern Italy and the colorism of Venice (Titian, Giorgione – though Giorgione died long before Caravaggio was born, his influence persisted).

In Rome, he encountered the dominant late Mannerist style of artists like the Cavaliere d'Arpino, whose artificiality he rejected. He also contended with the classicizing trend emerging with Annibale Carracci and his Bolognese academy, who also sought reform but through a synthesis of Renaissance ideals and naturalism. While Carracci and Caravaggio represented different paths for Baroque art, they were the two most innovative forces in Rome at the turn of the 17th century.

Caravaggio's interactions with other artists were often fraught. His libel case against Giovanni Baglione (a rival painter and later biographer) reveals professional jealousies. His relationship with Orazio Gentileschi was complex; they were associated in the libel suit but Gentileschi later became one of the most gifted painters influenced by Caravaggio's style. Mario Minniti, a Sicilian painter, was a friend and frequent model in Caravaggio's early Roman works. Key patrons like Cardinal del Monte and later Cardinal Scipione Borghese and the Marchese Vincenzo Giustiniani were crucial for his career, providing commissions and protection.

The Caravaggisti: A Legacy Across Europe

Despite his short career and controversial reputation, Caravaggio's impact was immediate and profound. His revolutionary style spawned a legion of followers and imitators across Europe, known collectively as the Caravaggisti. These artists adopted his dramatic chiaroscuro, intense realism, and focus on humble subjects, though often adapting his style to their own temperaments and local traditions.

In Italy, prominent followers included Orazio Gentileschi and his exceptionally talented daughter Artemisia Gentileschi, Bartolomeo Manfredi (who specialized in the tavern scenes Caravaggio had popularized), Carlo Saraceni, and Battistello Caracciolo in Naples. The Neapolitan school, in particular, remained heavily indebted to Caravaggio's example for decades, with artists like Jusepe de Ribera (Lo Spagnoletto), a Spaniard working in Naples, becoming a major exponent of tenebrism and gritty realism.

Caravaggio's influence spread rapidly beyond Italy. Dutch painters visiting Rome, particularly those associated with the Utrecht school like Hendrick ter Brugghen, Gerrit van Honthorst, and Dirck van Baburen, were captivated by his work. They brought Caravaggism back to the Netherlands, where it significantly influenced Rembrandt van Rijn's own exploration of light and psychological depth, and possibly indirectly impacted Johannes Vermeer's intimate genre scenes.

In Flanders, Peter Paul Rubens recognized Caravaggio's genius early on, advising the Duke of Mantua to purchase the Death of the Virgin and even copying Caravaggio's Entombment. While Rubens developed his own dynamic Baroque style, Caravaggio's impact is visible in his early work. In France, artists like Georges de La Tour developed a highly personal style of tenebrism, often featuring candlelit scenes with profound stillness and spiritual intensity. Valentin de Boulogne was another significant French Caravaggist working in Rome. In Spain, besides Ribera, the realism and dramatic lighting of Caravaggio resonated with painters like Francisco de Zurbarán and the young Diego Velázquez, whose early works clearly show his influence.

Controversy and Critical Reception

Caravaggio was as controversial in his time as he was influential. While his powerful realism and dramatic intensity were admired by many artists and some patrons, his work frequently provoked criticism and rejection. Detractors found his naturalism vulgar and lacking in decorum, particularly in religious subjects. His insistence on using ordinary, sometimes disreputable, models for sacred figures was seen as disrespectful or even blasphemous. The rejection of works like the first Saint Matthew and the Angel and the Death of the Virgin highlights this tension.

Critics like Giovanni Pietro Bellori, writing later in the 17th century, acknowledged Caravaggio's talent but criticized his perceived lack of invention, decorum, and reliance solely on the model without idealization. Classicist painters like Nicolas Poussin reportedly detested his work, believing he had come into the world to destroy painting. His violent life and rebellious personality undoubtedly colored contemporary perceptions of his art, reinforcing the image of a dangerous outsider challenging established norms.

Yet, the very aspects that drew criticism – the raw immediacy, the psychological penetration, the dramatic confrontation with reality – were also the source of his power and originality. He fulfilled the Counter-Reformation's call for art that could move the faithful, but he did so on his own terms, infusing religious narrative with unprecedented human drama.

Rediscovery and Enduring Influence

After the initial wave of Caravaggism faded by the mid-17th century, Caravaggio's reputation declined, and he fell into relative obscurity for centuries, overshadowed by the more classicizing tradition of Carracci or the High Baroque exuberance of artists like Gian Lorenzo Bernini.

It was not until the early 20th century that Caravaggio was rediscovered and his pivotal role in the history of art fully appreciated, thanks largely to the pioneering scholarship of Italian art historian Roberto Longhi. Longhi and subsequent generations of scholars recognized Caravaggio's revolutionary naturalism and dramatic lighting as foundational not only for the Baroque but also as a precursor to modern sensibilities.

Today, Caravaggio is celebrated as a towering genius. His influence is seen not only in the painters who followed him but also in later art forms. His dramatic lighting and compositional framing have been cited as influences on cinematography, particularly in film noir, and photography. Modern and contemporary artists, such as the Norwegian painter Odd Nerdrum or the Hungarian Tibor Csernus, have consciously drawn inspiration from his tenebrism and realism. Exhibitions of his work consistently draw huge crowds, testament to the enduring power of his art to shock, move, and fascinate audiences.

Conclusion

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio remains a figure of compelling contradictions: a man of violence who created works of profound spiritual depth, a fugitive from justice who received prestigious commissions, an artist criticized for vulgarity whose work reshaped European painting. His revolutionary use of light and shadow, his uncompromising realism, and his ability to capture moments of intense human drama transformed the artistic landscape of his time. Though his life was tragically short and marked by turmoil, his artistic legacy was immense. He challenged the conventions of his era, infused painting with a new level of psychological intensity and physical presence, and laid the groundwork for the Baroque style, leaving an influence that continues to resonate powerfully today. He truly was the master of light, shadow, and a reality that was both brutal and sublime.