Guido Reni stands as one of the most significant and influential painters of the Italian Baroque era. Active primarily in Bologna and Rome during the late 16th and early 17th centuries, Reni forged a distinctive style characterized by its classical grace, idealized beauty, and refined emotional tenor. His work, deeply rooted in the High Renaissance tradition yet responsive to the dramatic impulses of the Baroque, earned him immense fame during his lifetime and left a lasting legacy on European art. Navigating the complex artistic currents of his time, Reni absorbed lessons from masters like the Carracci and even the revolutionary Caravaggio, ultimately creating a path defined by elegance, harmony, and technical brilliance.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Bologna

Guido Reni was born in Bologna, likely on November 4th or 5th, 1575, into a family immersed in the world of music. His father, Daniele Reni, was a respected musician, and his mother, Ginevra Possi, also hailed from a musical background. This environment may have instilled in the young Guido an appreciation for harmony and structure, qualities that would later manifest in his art. Despite this musical heritage, Reni's calling lay in the visual arts.

At the tender age of nine, around 1584, Reni began his artistic training. He entered the bustling Bolognese workshop of the Flemish painter Denys Calvaert. Calvaert's studio was a notable training ground, and it was here that Reni first encountered other talented young artists who would become significant figures in their own right, including Francesco Albani and Domenichino. Working alongside these contemporaries, Reni learned the fundamentals of drawing and painting, likely absorbing Calvaert's Mannerist tendencies, characterized by elegant figures and sophisticated compositions.

However, Reni's ambition and artistic curiosity soon led him elsewhere. Around the age of twenty, circa 1595, he made a pivotal move, leaving Calvaert's studio to join the Accademia degli Incamminati ("Academy of the Progressives" or "Those Setting Out"). This innovative academy had been founded by the Carracci brothers – Ludovico, Agostino, and Annibale Carracci. The Carracci were spearheading a reform movement in Italian painting, reacting against the artificiality of late Mannerism by advocating a return to naturalism, drawing from life, and studying the masters of the High Renaissance, particularly Raphael and Correggio, as well as Venetian colorists like Titian.

The Accademia provided a stimulating environment where Reni honed his skills in drawing, anatomy, and composition. He deeply absorbed the Carracci's emphasis on classical principles, clarity of form, and emotional restraint, elements that would become hallmarks of his mature style. The influence of Annibale Carracci, in particular, with his blend of classicism and natural observation, was profound during this formative period. Reni quickly distinguished himself as one of the most promising talents within the Carracci circle.

The Roman Experience: Encountering Antiquity and Caravaggio

In the early 17th century, Rome was the undisputed center of the European art world, attracting ambitious artists from across the continent. Around 1601, Guido Reni, seeking greater opportunities and exposure, moved to the Eternal City. This period proved crucial for his artistic development, exposing him to the masterpieces of classical antiquity, the High Renaissance giants like Raphael and Michelangelo, and the radical innovations of his contemporary, Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio.

Upon arriving in Rome, Reni found opportunities to work on significant projects. He was involved in the completion of the fresco decorations in the Farnese Palace, a major undertaking led by Annibale Carracci. This experience allowed him to further refine his fresco technique and absorb Annibale's monumental classical style. He studied ancient Roman sculpture and Raphael's Vatican frescoes intensely, reinforcing his inclination towards idealized forms and balanced compositions.

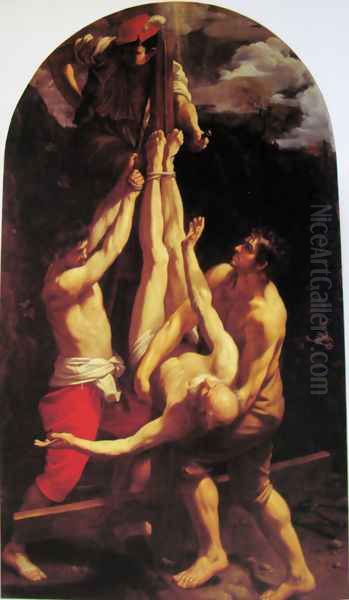

Simultaneously, Rome was captivated by the dramatic realism and intense chiaroscuro (the use of strong contrasts between light and dark) of Caravaggio. Reni could not ignore this powerful artistic force. While fundamentally different in temperament and aesthetic goals, Reni engaged with Caravaggio's style. Early Roman works, such as his powerful Crucifixion of St. Peter (c. 1604-1605, Vatican Pinacoteca), demonstrate a clear, albeit temporary, adoption of Caravaggesque elements: dramatic lighting, tenebrism, and a certain physical immediacy. The raw, unidealized depiction of the executioners contrasts with the more graceful rendering of the saint, perhaps showing Reni grappling with these opposing stylistic pulls.

Despite this engagement, Reni ultimately charted his own course. He seemed to consciously temper Caravaggio's raw naturalism and dark psychological intensity, preferring a more refined, lyrical, and idealized approach. His figures retained a classical poise and grace, even amidst dramatic scenes. This selective assimilation and ultimate divergence from Caravaggio highlight Reni's commitment to a different vision of Baroque art, one grounded in classical beauty and harmony rather than stark realism.

Masterpieces in Rome and the Rise to Fame

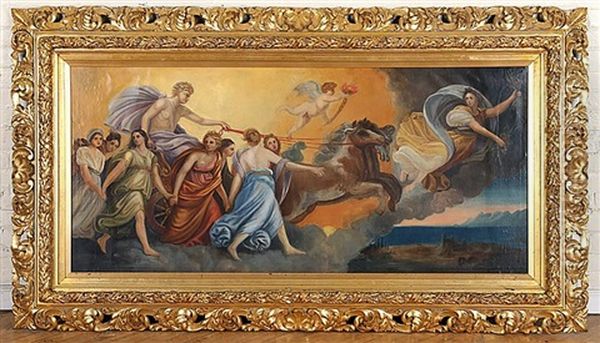

During his years in Rome, Reni secured prestigious commissions that cemented his reputation. One of his most celebrated works from this period is the ceiling fresco Aurora (1614), painted for Cardinal Scipione Borghese's garden palace, the Casino dell'Aurora, located on the Quirinal Hill. This masterpiece depicts Apollo in his chariot, led by Aurora (Dawn), scattering flowers, surrounded by the dancing Hours. It is a quintessential example of Reni's high Baroque classicism – a dynamic yet perfectly balanced composition, filled with graceful figures, bathed in luminous, pearlescent light, and imbued with an air of effortless elegance. It directly rivals Annibale Carracci's Farnese Gallery ceiling in its ambition and classical inspiration, but possesses a lighter, more lyrical touch.

The Aurora fresco became immensely famous, admired for its idealized beauty and masterful execution. It showcased Reni's ability to translate the grandeur of classical mythology into a visually stunning and harmonious composition, perfectly suited to the tastes of his elite patrons. It stood in stark contrast to the darker, more visceral works of Caravaggio and his followers, offering an alternative vision of Baroque grandeur rooted in grace and light.

Other significant works from his Roman periods include numerous altarpieces and devotional paintings. His depictions of saints like Mary Magdalene and Sebastian became particularly sought after. His St. Sebastian paintings, for example, often portray the saint not in the throes of gruesome martyrdom, but as an idealized, almost ethereal figure, gazing heavenward in serene acceptance, a treatment that appealed greatly to contemporary sensibilities. These works combined religious piety with a refined sensuality derived from classical sculpture.

However, Reni's time in Rome was not without friction. Competition among artists was fierce, and Reni reportedly had professional rivalries, including tensions with his former master Annibale Carracci and possibly other artists vying for papal and aristocratic patronage. These rivalries, combined perhaps with a desire to be the preeminent painter in his native city, contributed to his eventual decision to spend more time back in Bologna.

Return to Bologna and Artistic Dominance

Although Reni maintained connections with Rome and returned there periodically, Bologna became his primary base of operations from around 1614 onwards. He returned as a celebrated master, his Roman successes having significantly elevated his status. In Bologna, he quickly became the leading figure in the city's artistic scene, inheriting the mantle previously held by the Carracci, particularly after Annibale's death in 1609 and Ludovico's declining influence.

Back in his native city, Reni established a large and highly productive workshop. His fame attracted numerous patrons, including churches, religious orders, and private collectors, not only from Bologna but from across Italy and Europe. He received commissions for major altarpieces that further solidified his reputation. Among the most important Bolognese works is the Massacre of the Innocents (c. 1611, Pinacoteca Nazionale, Bologna). While possibly painted during a return visit before his final settling, it exemplifies his mature Bolognese style. Compared to his earlier Caravaggesque phase, the lighting is clearer, the composition more complex and balletic, and the emotions, though intense, are expressed through more formalized, classically inspired gestures. The painting balances horrific violence with a strange, almost detached elegance.

Another key work is the Pala della Peste (Plague Altarpiece) or Madonna and Child with Patron Saints of Bologna (1631-32, Pinacoteca Nazionale, Bologna), commissioned as a votive offering after the city was spared from a devastating plague. This large altarpiece showcases Reni's ability to handle complex multi-figure compositions with clarity and devotional power. The figures of the saints are rendered with characteristic grace, appealing to the Virgin and Child above in a harmonious arrangement bathed in soft, divine light.

His Assumption of the Virgin (c. 1617, Sant'Ambrogio, Genoa, though versions exist elsewhere) is often cited as a pinnacle of his ability to convey spiritual ecstasy through idealized form and luminous color. The upward movement, the graceful gestures of the Virgin, and the celestial light create a powerful image of divine transcendence. Reni excelled in depicting such moments of religious fervor with a sense of decorum and beauty that aligned perfectly with the ideals of the Counter-Reformation church.

Throughout his Bolognese period, Reni continued to produce numerous paintings of his favorite subjects: Madonnas, St. Sebastian, Mary Magdalene, David, Lucretia, Cleopatra, and various mythological scenes. His style became increasingly refined, characterized by a lighter palette, smoother brushwork, and an emphasis on graceful contours and serene expressions. He developed a particular mastery in rendering flesh tones and drapery with exquisite subtlety.

The Reni Workshop and Its Influence

Guido Reni's success was amplified by his highly organized and prolific workshop in Bologna. At its peak, it was one of the largest and most active studios in Italy, reportedly employing or training nearly two hundred assistants and pupils over the years. This "factory" allowed Reni to meet the enormous demand for his work, producing numerous originals, replicas, and variations of his most popular compositions.

The workshop was crucial not only for production but also for disseminating Reni's style. Many talented artists passed through his studio, absorbing his techniques and aesthetic principles. Among his most notable pupils were Simone Cantarini (also known as Il Pesarese), who developed a style close to Reni's but with a distinctive feathery brushwork and sensitivity, though their relationship eventually soured. Other significant students included Francesco Gessi, Giacomo Semenza, Antonio Randa, Vincenzo Gotti, Emilio Savoni, Sebastiano Brunetti, and Domenico Maria Canuti. Michele Desubleo (often mistakenly called Sobolo) and Ercole Ruggieri were also associated with his circle.

These artists helped to perpetuate the Reni "brand" of elegant Baroque classicism. While some, like Cantarini, developed independent careers, many continued to work in a style heavily indebted to their master. The sheer number of artists associated with Reni's workshop ensured that his influence permeated Bolognese painting for decades. Furthermore, the presence of female artists like Elisabetta Sirani, who, while primarily trained by her father (another Reni pupil), clearly admired and emulated Reni's style, speaks to his broad impact on the Bolognese art scene. Sirani became a successful painter in her own right, known for her rapid execution and Reni-esque compositions.

The workshop system, however, also contributed to issues of attribution that continue to challenge art historians today. Distinguishing between works entirely by Reni's hand, those executed with workshop assistance, and copies or variations produced by pupils can be difficult, especially given the high quality maintained by the studio and Reni's own practice of repeating successful compositions.

Later Years, Stylistic Evolution, and Controversy

Reni's later career, primarily spent in Bologna, saw a further evolution in his style, often referred to as his "second manner" or late style. This phase, dating roughly from the late 1620s or early 1630s until his death, is characterized by a significant lightening of his palette, employing cooler, silvery tones, and often unfinished-looking, looser brushwork. Compositions became simpler, focusing on fewer figures, often depicted half-length against neutral backgrounds. Examples include works like David Contemplating the Head of Goliath (versions exist, e.g., Louvre, Paris) and numerous depictions of Lucretia, Cleopatra, and Sibyls.

This late style was, and remains, a subject of debate among critics and art historians. Some contemporaries and later critics saw it as a decline, a falling off from the technical perfection and rich color of his middle period. They attributed the looser handling and rapid execution partly to Reni's notorious gambling habit, suggesting he was churning out works quickly to pay off debts. His biographer Carlo Cesare Malvasia, writing later in the 17th century, painted a picture of an artist increasingly burdened by his addiction, forced to paint hastily.

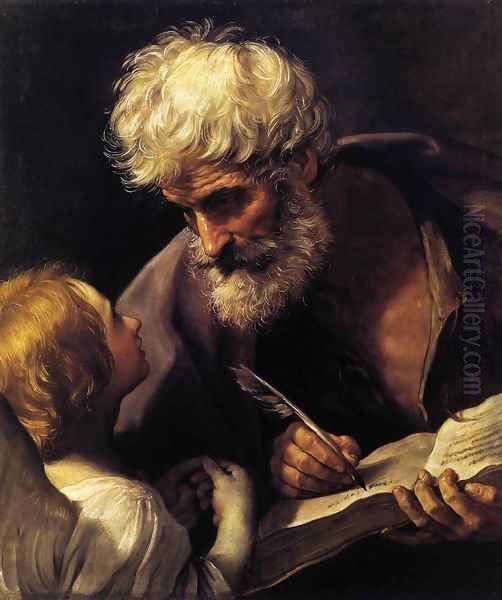

However, other interpretations view Reni's late style more positively. Modern scholarship often sees it as a deliberate artistic choice, a move towards greater abstraction, spiritualization, and painterly freedom. The silvery tones and dematerialized forms can be interpreted as conveying a heightened sense of spirituality or otherworldly grace. The seemingly "unfinished" quality might reflect an interest in capturing the essence of the subject rather than meticulous detail, perhaps anticipating later painterly developments. Works like his late St. Matthew and the Angel (Vatican Pinacoteca) possess a delicate, almost ethereal quality quite distinct from his earlier robustness.

Controversies also touched his personal life. Malvasia described Reni as deeply pious but also superstitious, prone to fears of witchcraft and poisoning, and possibly misogynistic. His gambling addiction was undoubtedly real and caused him significant financial distress, leading to legal troubles, such as disputes over debts he had guaranteed. This complex picture of a man capable of creating sublime images of divine grace while struggling with personal demons adds another layer to his biography. A brief, unhappy attempt to work in Naples around 1621-22, where he faced intense hostility and threats from local artists like Jusepe de Ribera and Belisario Corenzio, further illustrates the competitive and sometimes dangerous environment in which he operated.

Legacy and Art Historical Assessment

Guido Reni died in Bologna on August 18, 1642, at the age of 67. At the time of his death, he was one of the most famous and highly regarded painters in Europe. His influence was immediate and widespread. In Italy, his elegant classicism provided a dominant model, particularly in Bologna and Rome, offering a compelling alternative to the more dramatic naturalism of Caravaggio's followers or the exuberant High Baroque of artists like Pietro da Cortona or Gian Lorenzo Bernini (though Bernini, primarily a sculptor and architect, shared the Baroque era's interest in heightened emotion).

His impact extended far beyond Italy. In France, Reni's work was immensely admired throughout the 17th and 18th centuries. Artists like Eustache Le Sueur, Charles Le Brun, and Simon Vouet looked to his compositions for their clarity, grace, and decorum, making him a key source for French academic classicism. His paintings were eagerly collected by French royalty and aristocracy. In Spain, his idealized religious figures resonated with painters like Bartolomé Esteban Murillo, whose gentle Madonnas and saints owe a debt to Reni's prototypes.

However, Reni's reputation experienced significant fluctuations after his death. While revered for centuries as the "Divine Guido," his fame waned considerably in the 19th century. Critics like John Ruskin, championing earlier Italian art and later Romanticism, dismissed Reni's work as insincere, sentimental, and overly academic. His perceived smoothness and idealization were seen as lacking the emotional depth or rugged authenticity valued by Victorian taste.

The 20th century saw a gradual reassessment and rehabilitation of Reni's reputation. Art historians began to appreciate his technical mastery, the sophistication of his compositions, and the genuine emotional power underlying his idealized forms. Major exhibitions dedicated to his work helped to re-establish his importance as a central figure of the Baroque era, a master who skillfully synthesized the classical tradition with the new sensibilities of his time.

Today, Guido Reni is recognized as a pivotal artist who defined a particular strain of Baroque classicism. His ability to create images of sublime beauty, profound religious feeling, and mythological elegance remains compelling. His best works, such as the Aurora, the Massacre of the Innocents, and his numerous depictions of saints in ecstatic contemplation or serene martyrdom, continue to be admired for their technical brilliance, harmonious composition, and delicate handling of light and color. He stands as a testament to the diversity of the Baroque period, demonstrating that grandeur could be expressed not only through dramatic intensity but also through refined grace and idealized harmony. His complex life and evolving style continue to fascinate scholars and viewers alike, securing his place as a true master of Italian painting.