Qiu Ying (仇英, c. 1494–c. 1552), courtesy name Shifu (实父) and sobriquet Shizhou (十洲), stands as one of the most accomplished and intriguing figures in the history of Chinese painting. Active during the vibrant middle period of the Ming Dynasty, he is celebrated as one of the "Four Masters of the Ming" (明四家), alongside Shen Zhou, Wen Zhengming, and Tang Yin. Based primarily in the cultural hub of Suzhou, Qiu Ying carved a unique path, rising from humble artisan beginnings to become a highly sought-after painter revered for his technical brilliance, meticulous detail, and evocative depictions of diverse subjects. His work bridges the gap between professional craftsmanship and literati aesthetics, leaving behind a legacy of exquisite paintings that continue to captivate viewers centuries later. This exploration delves into the life, artistic achievements, stylistic characteristics, and enduring influence of this exceptional artist.

Humble Beginnings and Artistic Formation

Unlike his famous contemporaries Shen Zhou and Wen Zhengming, who hailed from established scholar-official families, Qiu Ying's origins were modest. Born in Taicang, Jiangsu province, his family later relocated to Suzhou, the epicenter of Wu School painting. His initial trade was not painting but lacquerwork, a craft demanding precision and patience – qualities that would profoundly shape his later artistic endeavors. This background as an artisan set him apart from the literati elite who dominated the art scene, yet it also equipped him with an exceptional foundation in manual dexterity and decorative sensibility.

The turning point in Qiu Ying's career came when his talent was recognized by the established painter Zhou Chen (周臣). Zhou Chen, himself a significant figure who bridged professional and literati styles and was a student of Shen Zhou's lineage, took Qiu Ying under his wing. This apprenticeship was crucial, providing Qiu Ying with formal training in the established painting techniques of the time, particularly the lineage tracing back to the Southern Song Imperial Academy masters. Interestingly, Zhou Chen also served as a teacher to Tang Yin, another of the Four Masters, linking Qiu Ying and Tang Yin through shared tutelage, though their artistic paths would diverge in significant ways.

Moving beyond his initial training, Qiu Ying immersed himself in the rich artistic environment of Suzhou. He diligently studied and copied the works of earlier masters, honing his skills and absorbing diverse stylistic influences. His artisan background, combined with rigorous training and an innate artistic sensibility, allowed him to develop a technical proficiency that few could rival. This dedication laid the groundwork for his eventual acceptance and renown within Suzhou's demanding artistic circles.

The Development of a Unique Style

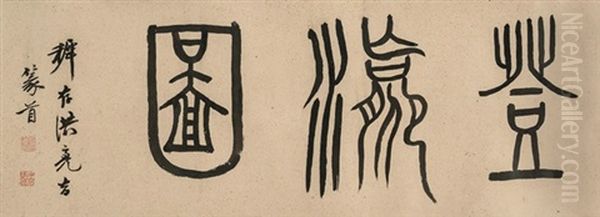

Qiu Ying's artistic signature lies in his mastery of the gongbi (工筆) or "fine-line" technique, often combined with rich, vibrant colors. He excelled particularly in the qinglü shanshui (青綠山水), or "blue-and-green landscape" style, a tradition dating back to the Tang dynasty but revitalized and adapted by Qiu Ying with remarkable finesse. His brushwork is characterized by its precision, control, and elegance. Lines are typically fine, strong, and fluid, meticulously delineating forms from the grandest mountain ranges to the most delicate architectural details or textile patterns.

His style represents a masterful synthesis of various traditions. He drew heavily upon the Southern Song Imperial Academy painters, particularly Li Tang (李唐), Liu Songnian (刘松年), Ma Yuan (马远), and Xia Gui (夏圭), inheriting their aptitude for structured compositions, detailed rendering, and atmospheric depth. Simultaneously, he looked further back, emulating the archaic elegance and decorative richness of Tang dynasty masters and figures like Zhao Boju (赵伯驹) and Zhao Mengfu (赵孟頫) of the Song and Yuan dynasties, especially in his use of mineral pigments for the blue-and-green style.

However, Qiu Ying did not merely replicate past styles. Living and working in Suzhou, he absorbed the refined aesthetics of the Wu School, characterized by its emphasis on elegance (雅), subtlety, and scholarly taste. While his technique remained rooted in professional precision, his subject matter, compositions, and overall mood often reflected the literati preference for depicting historical narratives, poetic themes, leisurely garden scenes, and idealized landscapes. This fusion resulted in works that were both technically dazzling and imbued with a sense of grace and refinement, appealing to a broad audience including scholars, officials, and wealthy merchants. His ability to blend meticulous craftsmanship with artistic sensitivity created a style that was uniquely his own – elaborate yet not overwrought, detailed yet possessing an inner vitality.

Mastery of Figures and Narrative Scenes

Figure painting was a domain where Qiu Ying's talents shone with particular brilliance. He is renowned for his depictions of historical events, mythological tales, palace life, and especially, elegant court ladies or 仕女画 (shìnǚhuà). His portrayals of women are so distinctive in their delicate beauty, refined postures, and exquisitely detailed attire that they are often referred to as the "Qiu style" or "Qiu school" of figure painting. He captured not just the outward appearance but also conveyed a sense of grace, poise, and sometimes, subtle emotion.

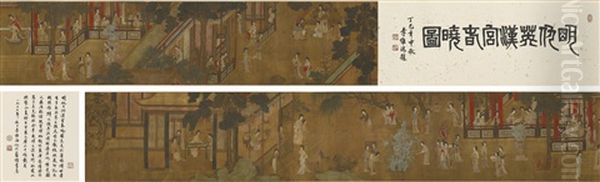

His narrative scrolls are masterpieces of storytelling through visual means. One of his most famous works in this genre is Spring Morning in the Han Palace (漢宮春曉圖). This long handscroll unfolds a panorama of life within the imperial palace, depicting numerous figures engaged in various activities – playing music, arranging flowers, reading, grooming, playing games. The level of detail in the architecture, furnishings, gardens, and costumes is astonishing, offering a glimpse into an idealized vision of courtly elegance and leisure. Each figure is carefully rendered, contributing to the overall richness and complexity of the composition.

Qiu Ying was also a highly skilled copyist of ancient masterpieces, a common practice for artists seeking to learn from the past and fulfill patrons' desires. Access to great collections, such as that of his patron Xiang Yuanbian, allowed him to study and replicate works by Tang and Song masters. A famous example often associated with him is a version of Emperor Taizong Receiving the Tibetan Envoy (步辇圖), originally by the Tang dynasty master Yan Liben (阎立本). While the original is a landmark work, Qiu Ying's rendition (or copies attributed to him) demonstrates his ability to capture the spirit and detail of ancient paintings, further showcasing his technical virtuosity and understanding of historical styles. These copies were not mere reproductions but interpretations that carried his own distinct refinement.

His figure paintings often populate his landscapes as well, never merely as scale elements but as integral parts of the scene, embodying the theme or narrative. Whether depicting scholars in conversation, fishermen on a river, or ladies enjoying a garden, his figures are rendered with the same meticulous care and attention to detail that characterize his broader work, bringing life and focus to his compositions.

Landscapes: Real and Imagined

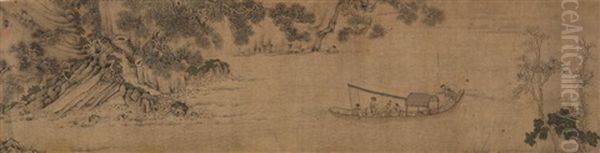

While renowned for his figure painting, Qiu Ying was also a highly accomplished landscape artist. His landscapes range from the intricate and colorful qinglü style to more subtle ink-wash paintings, though he is most celebrated for the former. He depicted both the familiar scenery of the Jiangnan region, particularly the gardens and waterways of Suzhou, and grand, imagined vistas inspired by classical themes and ancient masters.

His blue-and-green landscapes are particularly striking. Works like Peach Village Cottage (桃村草堂圖) or similar idyllic retreats showcase his ability to construct complex, multi-layered compositions filled with detailed rendering of mountains, trees, water, pavilions, and figures. He employed mineral pigments like azurite blue and malachite green with exceptional skill, creating landscapes that are visually sumptuous and jewel-like, evoking an archaic, almost mythical quality, yet grounded in meticulous observation of natural forms. The interplay of vibrant color and fine ink lines creates a distinctive decorative effect combined with spatial depth.

Qiu Ying also painted landscapes that seem to depict specific, real locations, particularly the famous gardens of Suzhou commissioned by their wealthy owners. These paintings serve not only as artistic creations but also as valuable historical documents of Ming dynasty garden design and the leisurely lifestyle of the elite. Works like the Garden for Solitary Enjoyment (獨樂園圖), depicting the garden of Sima Guang but likely reflecting contemporary garden aesthetics, exemplify this genre. Here, his precision was essential in capturing the intricate layouts, architectural elements, and carefully cultivated natural beauty of these private retreats.

Even in his ink landscapes, which are less numerous or famous than his colored works, Qiu Ying demonstrated considerable skill. Works like Pavilion by the Stream (臨溪水閣圖) or Scholar Conversing under Wutong Trees (桐陰清話圖) show his ability to handle ink wash and brushwork with sensitivity, creating atmosphere and texture. However, it is the combination of line, color, and intricate detail in his gongbi landscapes that truly defines his contribution to this genre, offering a powerful alternative to the more calligraphic and ink-focused styles prevalent among many literati painters of the Wu School.

Key Masterpieces

Qiu Ying's oeuvre includes numerous works that are considered pinnacles of Ming Dynasty painting. Several stand out for their technical mastery, compositional brilliance, and historical significance:

Spring Morning in the Han Palace (漢宮春曉圖): Arguably his most famous handscroll, this work is a tour-de-force of gongbi figure painting. It presents an idealized, sprawling vision of life among palace ladies, rendered with incredible detail in architecture, costume, and individual activities. It exemplifies his skill in handling complex compositions and large numbers of figures within a coherent narrative space.

Qingming Shanghe Tu (清明上河圖) - Qiu Ying version: Following the famous Song dynasty original by Zhang Zeduan (張擇端), Qiu Ying created his own version of the Along the River During the Qingming Festival theme. While inspired by the original's panoramic depiction of urban life, Qiu Ying's version reflects the society, architecture, and customs of the Ming Dynasty, particularly Suzhou. It is executed in his characteristic meticulous style with vibrant colors, offering a fascinating comparison to the Song original and showcasing Ming urban prosperity.

Peach Village Cottage (桃村草堂圖): This work, or others with similar titles depicting scholarly retreats, showcases his mastery of the blue-and-green landscape style. It typically features intricate mountain settings, lush vegetation, elegant pavilions, and scholarly figures engaged in leisurely pursuits, embodying the idealized literati life within a visually stunning natural environment. The detailed brushwork and rich coloration are hallmarks of his landscape art.

Garden for Solitary Enjoyment (獨樂園圖): Representing his skill in depicting specific (though perhaps idealized) locations, this painting portrays a famous historical garden. It highlights his ability to render complex architectural arrangements and garden layouts with precision, populated by figures that animate the space and suggest the scholarly pursuits associated with such environments.

Journey to Shu (蜀道圖): Often attributed to Qiu Ying, this handscroll depicts the dramatic mountain passes of Sichuan, famous for their treacherous beauty. Whether a direct work or a close copy, it demonstrates the ability to convey immense scale and rugged terrain through detailed brushwork, capturing the awe-inspiring and dangerous nature of the landscape described in classical literature.

Wang Xizhi Writing on Fans (右軍書扇圖): This painting illustrates a famous anecdote about the Jin dynasty calligrapher Wang Xizhi. It exemplifies Qiu Ying's skill in historical figure painting, capturing the essence of the narrative and the character of the historical figure within a carefully composed setting.

These masterpieces, among many others like Playing the Qin Beneath Willows (柳下眠琴圖) and Spring Excursion Returning Late (春游晚归图), solidify Qiu Ying's reputation. They demonstrate his versatility across genres – figure, landscape, narrative – and his consistent dedication to technical perfection and aesthetic refinement.

The Wu School Context and Artistic Circle

Qiu Ying operated within the flourishing artistic milieu of the Wu School (吴门画派), centered in Suzhou. This school, largely defined by the works and influence of Shen Zhou (沈周) and his student Wen Zhengming (文徵明), emphasized the integration of poetry, calligraphy, and painting, drawing inspiration from Yuan dynasty literati masters and advocating for scholarly elegance and personal expression. While Qiu Ying shared the geographical location and some aesthetic goals with the Wu School, his position within it was unique due to his professional background and stylistic focus.

His relationship with the other "Four Masters" is noteworthy. He studied under Zhou Chen, who was also Tang Yin's (唐寅) teacher, creating an indirect link. While records of direct interaction with the elder Shen Zhou are scarce, Qiu Ying was certainly aware of his monumental influence. His connection with Wen Zhengming was significant; Wen, the leading figure of the Wu School after Shen Zhou, reportedly admired Qiu Ying's skill. Some accounts suggest Qiu Ying sought guidance from Wen, and works like Studio Among Wutong and Bamboo (梧竹書堂圖) were painted by Qiu for Wen, indicating mutual respect. Qiu Ying's meticulousness may have resonated with certain aspects of Wen's own detailed early style.

His friendship with Tang Yin, another figure who navigated between professional skill and literati aspirations, seems to have been closer. Both studied with Zhou Chen, and both possessed extraordinary technical facility. While Tang Yin was perhaps more flamboyant in life and art, incorporating bolder ink play, they shared an ability to create highly refined and popular works. Legends of their interactions exist, including collaborations like the Peach Haven scroll (桃渚圖), suggesting a collegial relationship.

Qiu Ying's meticulous, often colorful style contrasted with the more calligraphic, ink-centric approaches favored by Shen Zhou and Wen Zhengming in their mature phases. Yet, his work was highly valued within the same circles. He associated with and was influenced by other Wu School painters like Wen Zhengming's talented relatives Wen Boren (文伯仁) and Wen Jia (文嘉), as well as figures like Lu Zhi (陸治) and Qian Gu (錢榖), who also specialized in detailed landscapes and figure paintings. His presence enriched the Wu School, demonstrating that technical mastery derived from professional training could coexist with and complement literati ideals. His success highlights the diversity within the Wu School, which, while centered on literati values, also accommodated exceptional talents from different backgrounds. It's also useful to contrast the Wu School's refined aesthetics with the bolder, more dramatic style of the contemporary Zhe School (浙派), led by figures like Dai Jin (戴進) and Wu Wei (吳偉), which continued the Southern Song academy tradition in a different manner.

Patronage and Social Ascent

As a professional painter without the independent means or official connections of many literati artists, Qiu Ying relied heavily on commissions and patronage throughout his career. His exceptional skill, however, attracted a clientele that included not only wealthy merchants but also high-ranking officials and renowned scholar-collectors. This patronage was crucial not only for his livelihood but also for his artistic development and reputation.

One of his most significant patrons was the great collector Xiang Yuanbian (項元汴). Spending extended periods at Xiang's residence, Qiu Ying had unparalleled access to one of the finest private collections of ancient calligraphy and painting in China. This opportunity allowed him to study and meticulously copy masterpieces from the Tang and Song dynasties, profoundly enriching his understanding of historical styles and refining his own technique. Many of his copies of ancient works likely date from his time with Xiang. Other patrons included figures like Zhou Fenglai (周凤来) and Chen Guan (陈官).

Working for patrons often meant fulfilling specific requests, such as painting portraits, depicting favorite gardens, illustrating historical themes, or creating decorative works. Qiu Ying's versatility and technical reliability made him exceptionally well-suited to this role. He could adapt his style to suit the subject matter and the patron's taste, producing everything from intimate album leaves to monumental scrolls. His background as a craftsman may have made him more amenable to the demands of patronage than some independent-minded literati artists.

Despite his humble origins and professional status, Qiu Ying achieved remarkable social ascent through his artistic talent. He navigated the complex social landscape of Suzhou, earning the respect and friendship of elite scholars and collectors. Anecdotes tell of his interactions with figures like the scholar Wang Chong (王寵), for whom he painted, gaining admiration from Wen Zhengming and others. His success story is a testament to the possibility of social mobility through exceptional skill in the arts during the Ming Dynasty, challenging the rigid hierarchy that often separated artisans from the literati class. His ability to bridge this divide contributed significantly to his unique position in Chinese art history.

Legends, Legacy, and Enduring Influence

Qiu Ying's life, particularly his early years and exact dates, remains somewhat shrouded in mystery due to limited contemporary documentation – a reflection, perhaps, of his non-literati background, as scholars often documented their own circles more thoroughly. His epitaph is notably brief. This lack of detailed record has allowed certain legends to flourish, such as tales emphasizing his prodigious talent or specific interactions with patrons and fellow artists. Even details about his family, like his daughter Qiu Zhu (仇珠), also a painter known for her depictions of ladies in his style, are relatively scarce. A grandson was rumored to be deaf-mute.

His immense popularity during his lifetime and shortly after led to a significant challenge for later connoisseurs: the proliferation of copies, imitations, and outright forgeries bearing his name. The term "Suzhou fakes" (蘇州片, Sūzhōu piàn) often refers to commercially produced paintings in the Ming and Qing dynasties that frequently imitated Qiu Ying's popular style, particularly his colorful depictions of beauties and narrative scenes. Disentangling authentic works from this mass of imitations remains a complex task for art historians. However, the very existence of so many copies attests to the widespread appeal and influence of his art.

Qiu Ying's legacy lies in his establishment of an incredibly high standard for gongbi painting. He demonstrated that meticulous technique and rich coloration could achieve a level of refinement and artistic expression equal to the more esteemed literati ink painting. His work provided a model for later generations of professional artists and court painters in the Ming and Qing dynasties who specialized in detailed and colorful styles. Artists like You Qiu (尤求) in the later Ming clearly followed in his stylistic footsteps.

His influence extends beyond direct stylistic imitation. By successfully navigating the worlds of professional craftsmanship and elite patronage, he helped to elevate the status of the professional painter. His synthesis of Song academy traditions (Li Tang, Liu Songnian, etc.) with Yuan and Ming literati aesthetics (drawing inspiration from figures like Zhao Mengfu and the Wu School milieu) created a powerful and enduring artistic paradigm. His references to and copies of ancient masters like Yan Liben and Zhang Zeduan also reinforced the connection to classical traditions. Qiu Ying remains a pivotal figure, representing a unique confluence of technical mastery, historical consciousness, and artistic adaptation within the vibrant culture of the Ming Dynasty.

Conclusion

Qiu Ying occupies a vital and distinctive place in the grand narrative of Chinese art. Rising from the world of artisans, he achieved mastery through dedication, innate talent, and immersion in the rich traditions of the past and the vibrant artistic environment of Ming Dynasty Suzhou. As one of the Four Masters of the Ming, he stands alongside Shen Zhou, Wen Zhengming, and Tang Yin, yet his art offers a unique perspective, characterized by unparalleled technical precision, luminous color, and a remarkable ability to synthesize courtly refinement, professional skill, and literati sensibilities.

His paintings, whether depicting the bustling life of palaces and cities, the serene beauty of gardens and landscapes, or the elegant poise of historical figures and court ladies, are executed with a meticulousness that continues to inspire awe. He not only mastered the demanding gongbi technique but infused it with life and grace. His work provided a crucial link between the academic traditions of the Song dynasty and the evolving tastes of the Ming, influencing countless later artists and becoming one of the most sought-after and imitated styles in Chinese history. Qiu Ying's legacy endures in his breathtaking masterpieces, which remain treasured examples of the brilliance and diversity of Ming Dynasty art.