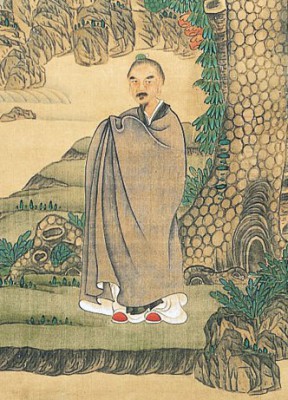

Chen Hongshou (陈洪绶, 1598–1652), also known by his courtesy name Zhanghou (章侯) and his most famous sobriquet Laolian (老莲, "Old Lotus"), stands as one of the most distinctive and influential artists in the tumultuous transition period from the Ming to the Qing dynasty in China. A native of Zhuji, near Shaoxing in Zhejiang province, Chen was a multifaceted talent, excelling as a painter, calligrapher, poet, and even a designer of intricate woodblock prints. His life, marked by personal tragedy and societal upheaval, profoundly shaped his art, leading to a body of work celebrated for its "gaogu qihai" (高古奇骇) – a unique blend of archaism, loftiness, eccentricity, and startling power. This exploration delves into the life, artistic innovations, key works, and enduring legacy of this remarkable figure who left an indelible mark on Chinese art history.

Early Life and Prodigious Beginnings

Born into a scholar-official family, Chen Hongshou's artistic inclinations were evident from an astonishingly young age. Legend has it that at the tender age of four, he painted a large, imposing portrait of Guan Yu, the revered general, on a newly whitewashed wall, much to the amazement of onlookers. This early display of talent was not a fleeting fluke. By the age of nine or ten, he was already receiving formal instruction. His initial tutelage in painting came under Lan Ying (蓝瑛, c. 1585–1664 or later), a prominent late Ming painter and a leading figure of the Wulin School (武林派), later considered the last great master of the Zhe School (浙派). Under Lan Ying, Chen would have honed his skills, particularly in landscape and flower-and-bird painting, absorbing the technical proficiency and stylistic tendencies of his teacher.

However, Chen Hongshou was not one to be confined by a single influence. His intellectual curiosity led him to the teachings of Liu Zongzhou (刘宗周, 1578–1645), a highly respected Neo-Confucian scholar and official known for his integrity and moral fortitude. While Liu Zongzhou was not primarily an art teacher, his emphasis on character, moral cultivation, and a deep understanding of classical principles likely had a profound impact on Chen's worldview and, indirectly, his artistic philosophy. This period also saw Chen immerse himself in the study of earlier masters, diligently copying and analyzing works from the Tang (618–907), Song (960–1279), and Yuan (1271–1368) dynasties. He particularly admired and sought to emulate the linear precision of artists like Li Gonglin (李公麟, c. 1049–1106) and the expressive power of Tang masters such as Wu Daozi (吴道子, c. 680–759).

His formative years were also marked by personal loss. He lost his father at a young age, an event that perhaps contributed to a certain melancholy and introspection that can be sensed in some of his later works. Despite these challenges, his reputation as a gifted artist began to grow.

A Path Diverged: From Aspiring Official to Reclusive Artist

Like many educated men of his time, Chen Hongshou initially pursued a career in the civil service through the imperial examination system. However, success eluded him in this endeavor. He made several attempts to pass the provincial examinations but was ultimately unsuccessful. This repeated failure, common for many talented individuals in a highly competitive system, likely steered him more decisively towards a professional artistic career.

During the Chongzhen era (1627–1644), Chen Hongshou's artistic fame reached the capital, Beijing. He was summoned to the imperial court, not as an official, but as an artist, likely to serve in the capacity of a gongfeng (供奉), or court painter. His task involved copying portraits of past emperors and meritorious officials. This experience provided him with unparalleled access to the imperial collection, allowing him to study masterpieces firsthand. However, Chen's independent spirit and perhaps a growing disillusionment with the pervasive corruption and political instability of the declining Ming court made him ill-suited for the rigid and often sycophantic environment of palace life. He soon grew weary of his duties and the constraints of courtly expectations, eventually resigning from his post and returning to the south.

The cataclysmic fall of the Ming dynasty in 1644 and the subsequent Manchu conquest profoundly impacted Chen Hongshou. Like many loyal to the Ming, he was deeply distressed by the collapse of the dynasty and the ensuing chaos. To escape the turmoil and perhaps as a gesture of resistance or despair, he sought refuge in a Buddhist monastery, specifically the Yunmen Temple (云门寺). He was tonsured as a monk and adopted monastic names such as Huichi (悔迟, "Regretting Late" or "Repentant Latecomer") and Laochi (老迟, "Old and Late"). This period of monastic life, however, was not permanent. After some time, he returned to secular life, though the experience undoubtedly left a mark on his psyche and artistic expression.

In the ensuing years under the nascent Qing dynasty, Chen Hongshou lived a reclusive life, primarily in his native Zhejiang. He supported himself by selling his paintings, a common recourse for scholar-artists who refused to serve the new regime. His art from this period often carries a palpable sense of sorrow, nostalgia for the fallen Ming, and a profound introspection, sometimes manifesting in even more exaggerated and unconventional forms.

The Unmistakable Style: "Gao Gu Qi Hai"

Chen Hongshou's artistic style is one of the most recognizable in Chinese art history. It is often summarized by the phrase "gaogu qihai" (高古奇骇), signifying a style that is at once lofty and archaic (gaogu) yet strange and startling (qihai). This unique aesthetic was not developed in a vacuum but was a conscious synthesis of ancient traditions and his own idiosyncratic vision.

His figure paintings, for which he is most renowned, are characterized by several distinct features. The figures themselves often appear elongated, with disproportionately large heads or hands, and a certain stiffness or monumentality that recalls archaic sculpture or earlier painting traditions, such as those of Gu Kaizhi (顾恺之, c. 344–406) from the Six Dynasties period. Chen deliberately eschewed the then-fashionable elegance and naturalism for a more stylized and expressive approach. His lines are typically described as "jinxi qingyuan" (劲细清圆) – strong yet fine, clear and rounded. This meticulous, almost wiry linearity defines forms with precision and imbues them with a sense of tension and energy. The drapery of his figures is often complex, with sharp, angular folds that contribute to the overall sense of archaism and decorative patterning.

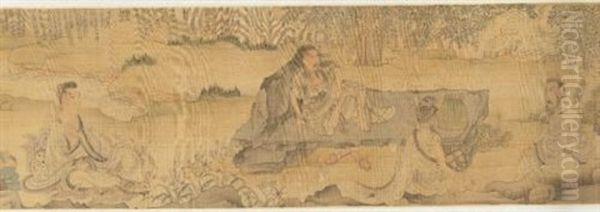

Chen's compositions are often bold and unconventional, sometimes featuring figures in unusual poses or stark, minimalist settings that heighten their psychological presence. He had a remarkable ability to capture the inner spirit and character of his subjects, whether they were historical figures, literary characters, or Buddhist deities. There is often an element of the theatrical or the grotesque in his work, a deliberate departure from conventional beauty towards what some have termed "chouzhiwei mei" (丑之为美) – the beauty of ugliness, or finding aesthetic value in the unconventional and the imperfect. This approach allowed him to convey complex emotions and satirical undertones.

Masterpieces Across Genres

While figure painting was his forte, Chen Hongshou's artistic talents extended to other genres, including flower-and-bird painting, landscape, and, notably, woodblock print design.

Figure Paintings:

Many of Chen's most celebrated works are his figure paintings. Lady Xuanwenjun Expounding the Classics (宣文君授经图) showcases his ability to depict historical narratives with a solemn, archaic grandeur. His figures are statuesque, their robes rendered with intricate, angular folds. Yang Sheng'an Pinning Flowers in His Hair (升庵簪花图轴), depicting the Ming scholar Yang Shen, is a quintessential example of his eccentric portraiture, capturing a moment of whimsical defiance. Drinking Wine and Reading "Encountering Sorrow" (饮酒读骚图) portrays a scholar, possibly a self-representation, finding solace in literature and wine, a common theme among disillusioned intellectuals. His depictions of Qu Yuan, such as Qu Yuan Chanting While Walking (屈子行吟图), resonate with a profound sense of tragic heroism, a sentiment Chen likely shared. Other notable figure paintings include The Drunken Simpleton (醉憨图), Copy of Li Gonglin's Begging Scholar (摹李公麟乞士图轴), Ruan Xiu Buying Wine (阮修沽酒图轴), and Lady at the Mirror (对镜仕女图).

Flower-and-Bird Paintings:

In his flower-and-bird paintings, Chen Hongshou combined the meticulous observation of Song dynasty academic painting with his own penchant for stylization and archaism. Works like Plum Blossoms and Small Bird (梅花小鸟) and Lotus and Mandarin Ducks (荷花鸳鸯图) demonstrate his fine brushwork and ability to capture the essence of his subjects. His flowers are often rendered with a crisp, almost metallic quality, and his birds and insects are imbued with a lively, sometimes quirky character. New Year Offerings (岁朝清供图) and Peace and Auspicious Omens (和平呈瑞图) are examples of auspicious themes handled with his distinctive touch. He was particularly skilled at depicting butterflies, their delicate patterns rendered with exquisite detail.

Landscape Paintings:

Though less numerous than his figure or flower-and-bird paintings, Chen's landscapes are also distinctive. They often feature archaic forms, angular rock formations, and a somewhat stark, simplified composition, as seen in works like Whistling Freely in an Autumn Forest (秋林啸傲图). His Album of Landscapes, Objects, and Flowers (山水物件花卉册) showcases his versatility across genres, with landscapes that possess a unique, slightly unsettling beauty, emphasizing structural forms over atmospheric effects.

Pioneering Woodblock Prints:

Chen Hongshou made significant contributions to the art of woodblock printing, elevating it to a new level of artistic sophistication. His designs for playing cards, known as yezi (叶子), are particularly famous. The Water Margin Playing Cards (水浒叶子), also known as Bogu Yezi (博古叶子, Antiquarian Playing Cards), feature forty unique designs depicting characters from the classic novel Water Margin. Each figure is rendered with incredible dynamism and individuality, showcasing Chen's mastery of line and characterization even within a small format. These prints were immensely popular and widely influential.

He also created illustrations for literary works, most notably for editions of the Nine Songs (九歌图), a series of shamanistic poems attributed to Qu Yuan, and for the romantic drama Romance of the West Chamber (西厢记). His print designs are characterized by their strong, clear lines, dramatic compositions, and expressive figures, perfectly suited to the woodblock medium. These works helped to popularize these literary classics and set a new standard for book illustration. Other print series include depictions of historical and legendary figures, further demonstrating his wide-ranging interests.

Calligraphic Achievements:

While primarily known as a painter, Chen Hongshou was also an accomplished calligrapher. His calligraphy, like his painting, often exhibits a preference for archaic forms and a strong, individualistic style. He was skilled in various scripts, but his works in running-cursive script (行草书), such as his Poetry Scroll in Running-Cursive Script (行草诗卷), and his letters, like the Short Letter to Third Brother (致三兄短札), reveal a vigorous and expressive hand. His calligraphic lines often possess a similar tensile strength and deliberate archaism found in his paintings.

A Network of Scholars and Artists: Friends and Influences

Chen Hongshou moved within a vibrant circle of intellectuals and artists, and his interactions with them were crucial to his development and career. His early teacher, Lan Ying, provided a solid foundation in painting techniques. The moral and philosophical guidance of Liu Zongzhou shaped his character.

He was a contemporary of Cui Zizhong (崔子忠, c. 1574–1644), another highly individualistic figure painter from the north. Together, they were famously known as "Nan Chen Bei Cui" (南陈北崔 – "Chen of the South, Cui of the North"), acknowledging their comparable stature and distinct, somewhat eccentric styles that stood apart from the mainstream Orthodox School masters like Wang Shimin (王时敏, 1592–1680) or Wang Jian (王鉴, 1598–1677), who followed the artistic theories of Dong Qichang (董其昌, 1555–1636). While Dong Qichang's influence was pervasive, Chen Hongshou forged a more independent path, drawing inspiration from earlier, pre-Yuan traditions.

Chen maintained close friendships with prominent literary figures of his time. One of his closest friends was Zhang Dai (张岱, 1597–1689), a renowned essayist and historian known for his vivid recollections of late Ming life. Their friendship was one of mutual admiration and intellectual camaraderie; they collaborated on projects, and Zhang Dai wrote appreciatively of Chen's art. Chen also had connections with the Qi family of Shaoxing, including Qi Biaojia (祁彪佳) and Qi Zhijia (祁豸佳), who were influential scholars and patrons. He also associated with the playwright Meng Chengshun (孟称舜), for whose works Chen sometimes provided illustrations or commendatory prefaces.

Among painters, besides Lan Ying, he associated with Sun Di (孙杕), another artist who provided him with guidance. There are also connections noted with Zeng Jing (曾鲸, 1564–1647), a master portraitist known for his "Bochen School" (波臣派) style that emphasized realism and psychological depth; Chen's own approach to portraiture, while more stylized, shared an interest in capturing the subject's essence. Zhou Lianggong (周亮工, 1612–1672), a prominent scholar, official, and art collector, was an admirer and patron of Chen Hongshou, and Chen painted portraits for him.

While Xu Wei (徐渭, 1521–1593), the great Ming individualist painter, calligrapher, and poet, died before Chen was born, Chen Hongshou is often seen as an artistic successor to Xu Wei's fiercely independent and expressive spirit. Chen deeply admired Xu Wei's untrammeled creativity and bold, unconventional style.

Later Years: Art as a Reflection of a Troubled Soul

The latter part of Chen Hongshou's life was lived under the shadow of the Qing conquest. His personal experiences of loss—his father early in life, his wife in middle age, and the fall of his dynasty—coupled with the general hardship and uncertainty of the times, deeply affected his art. His works from this period often exhibit an intensified exaggeration, a more profound sense of melancholy, and even a touch of the bizarre or grotesque. The "startling" (骇) aspect of his "gaogu qihai" style became more pronounced.

His figures might appear even more attenuated or contorted, their expressions conveying a wider range of complex, often somber emotions. There's a philosophical depth and a poignant sense of tragedy in many of these later works. They reflect not only his personal sorrows but also the collective trauma of a generation that witnessed the collapse of a world they knew. His art became a vehicle for expressing his disillusionment with worldly affairs, his nostalgia for the past, and his unwavering commitment to his own artistic principles in an era of profound change. Despite the hardships, he continued to create prolifically, his art a testament to his resilience and enduring creative fire. He passed away in 1652, at the age of fifty-four (by traditional Chinese reckoning).

Enduring Legacy and Historical Significance

Chen Hongshou's impact on Chinese art history is profound and multifaceted. He is regarded as one of the last great masters of the Ming dynasty and a pivotal figure who bridged the artistic traditions of the Ming and Qing periods. His highly individualistic style, characterized by its archaism, expressive power, and often eccentric figural representation, offered a potent alternative to the dominant Orthodox School.

His influence was felt by subsequent generations of artists. Qing dynasty masters such as the "Four Monks"—Shitao (石涛, 1642–1707) and Bada Shanren (八大山人, born Zhu Da, 1626–1705) in particular—with their own unconventional approaches, show affinities with Chen's spirit of artistic independence, even if their styles differed. Later, the artists of the Yangzhou School, such as Jin Nong (金农, 1687–1763) and Huang Shen (黄慎, 1687–1772), who also emphasized individuality and eccentricity, can be seen as inheritors of this tradition. The Shanghai School painters of the 19th century, notably Ren Xiong (任熊, 1823–1857), Ren Xun (任薰, 1835–1893), and Ren Yi (任颐, also known as Ren Bonian, 1840–1896), explicitly drew inspiration from Chen Hongshou's figure painting style, particularly his strong linearity and expressive distortions.

His woodblock prints had an enormous impact, not only in China but also in neighboring countries like Japan, where they influenced Ukiyo-e artists. The accessibility of prints meant that his distinctive style reached a much wider audience than his paintings alone could have.

In the 20th century, Chen Hongshou's reputation continued to grow. The influential writer and cultural critic Lu Xun (鲁迅, 1881–1936) was a great admirer of Chen's work, particularly his prints, and played a role in reviving interest in his art. Modern and contemporary Chinese artists have also looked to Chen Hongshou as a model of artistic integrity and innovation. International scholars now widely recognize him as, in the words of James Cahill, "one of the most thoroughly individual and distinctive artists of the entire later history of Chinese painting," and a figure who represents "the first stirrings of a truly alienated art" in China.

His art continues to be studied and celebrated for its technical brilliance, its profound emotional depth, and its unique synthesis of tradition and radical innovation. Chen Hongshou's ability to infuse ancient forms with a vibrant, contemporary sensibility, and to express complex human emotions through his distinctive visual language, secures his place as a towering figure in the annals of Chinese art. His life and work serve as a powerful reminder of the enduring connection between personal experience, historical context, and artistic creation.