Abbott Fuller Graves stands as a significant figure in American art history, particularly noted for his contributions to Impressionism during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Born in Weymouth, Massachusetts, in 1859, Graves carved a niche for himself with his luminous depictions of gardens, floral still lifes, and scenes of New England life. His journey from a working-class background to becoming a celebrated painter and influential teacher reflects both personal determination and the shifting artistic currents of his time. Known for his vibrant palette, textured brushwork, and masterful handling of light, Graves captured the ephemeral beauty of nature, leaving behind a body of work that continues to enchant viewers today.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Abbott Fuller Graves entered the world in Weymouth, Massachusetts, on April 15, 1859. His family background was modest, rooted in the working class. Financial difficulties marked his childhood, compelling him to leave formal schooling at an early age. To help support his family, the young Graves found work in a local greenhouse. This early immersion in the world of horticulture likely planted the seeds for his lifelong fascination with flowers and gardens, subjects that would later dominate his artistic output. Though practical necessity dictated his early employment, an artistic inclination began to surface.

Initially, Graves harbored ambitions of becoming an architect. This led him to enroll at the prestigious Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). However, his studies in architecture were short-lived, and he did not complete the program. The structured world of blueprints and building design ultimately gave way to a stronger pull towards the fine arts. This pivotal shift redirected his path towards painting, setting the stage for his future career.

His formal art education began in Boston, a burgeoning center for American art. Graves enrolled in classes at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Here, he honed his foundational skills and absorbed the prevailing artistic theories. During this formative period, he encountered fellow students and instructors who would shape his development, most notably Edmund C. Tarbell, who would become a lifelong friend and a prominent figure in the Boston School of painting. The influence of the Boston art scene, with its blend of academic tradition and burgeoning Impressionist sensibilities, was crucial in shaping Graves's early artistic identity.

Parisian Studies and Impressionist Immersion

The allure of Europe, particularly Paris, the undisputed capital of the art world in the late 19th century, beckoned many aspiring American artists. In 1884, Graves embarked on this transformative journey, traveling overseas with his close friend, Edmund Tarbell. This period abroad was instrumental in refining his technique and broadening his artistic horizons. In Paris, Graves and Tarbell shared lodgings, creating an environment of mutual support and artistic exchange as they navigated the vibrant Parisian art scene.

Graves sought instruction from established masters. He studied under Georges Jeannin, a French painter renowned for his exquisite flower paintings. Jeannin's influence is palpable in Graves's later dedication to floral subjects and his skillful rendering of textures and light on petals and leaves. The academic training received under Jeannin provided Graves with a solid technical foundation, even as he began to explore more modern stylistic approaches.

During his time in Paris, Graves also forged a significant friendship with another American artist, Frederick Childe Hassam. Hassam was already embracing Impressionism, and his enthusiasm for the style, characterized by its bright colors, broken brushwork, and focus on capturing fleeting moments of light and atmosphere, deeply influenced Graves. Exposure to the works of French Impressionist masters like Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and Camille Pissarro, whether in galleries or studios, further solidified this stylistic shift. Graves began experimenting with the techniques of Impressionism, incorporating its principles into his own developing aesthetic. He also spent time studying in Italy, further enriching his understanding of European art traditions before returning to the United States.

Return to Boston: Teaching and Establishing a Reputation

Upon returning to Boston around 1885 or 1886, Graves brought back the techniques and inspirations gleaned from his European sojourn. He quickly integrated himself into the city's active art community. His skills and European experience earned him a teaching position at the Cowles Art School in Boston, where he began instructing in 1886. Notably, his friend Childe Hassam also taught at Cowles during this period, reinforcing their connection and likely fostering an environment where Impressionist ideas were discussed and disseminated among students.

Graves's reputation as both an artist and an educator grew. In 1891, demonstrating his ambition and confidence, he opened his own art school in Boston. His curriculum focused primarily on landscape and figure painting, areas where he could impart the principles he had absorbed, including the Impressionist emphasis on light, color, and direct observation. This venture allowed him to cultivate a following and contribute directly to the training of a new generation of artists in the region.

During his Boston years, Graves actively exhibited his work. He was associated with the Boston Art Club, showcasing his paintings there as early as 1878, even before his European trip. However, his relationship with the club was not without friction; reports suggest he later resigned due to dissatisfaction with its exhibition policies. Despite this, he remained a visible presence in the Boston art world, his paintings gaining recognition for their decorative appeal and skillful execution. His subjects often included the gardens and floral arrangements that would become his signature, alongside depictions of local life. He was considered part of the broader movement often referred to as the Boston School, though his focus differed somewhat from the elegant interior figure studies favored by colleagues like Tarbell and Frank Weston Benson.

The Kennebunkport Years: Gardens and Coastal Life

Seeking a change of scenery and perhaps a closer connection to the natural landscapes that inspired him, Abbott Fuller Graves made a significant move in 1895. He relocated to the coastal town of Kennebunkport, Maine. This picturesque location, already attracting artists drawn to its maritime charm and scenic beauty, would become Graves's primary base for the remainder of his life and career. The move marked a shift away from the urban environment of Boston towards a setting that profoundly influenced his art.

In Kennebunkport, Graves found endless inspiration in the local gardens, coastal vistas, and the rhythm of village life. He established another art school, continuing his passion for teaching while immersing himself in his own creative work. The gardens of Kennebunkport, both cultivated and wild, became his principal subject matter. His paintings from this period often feature sun-drenched floral arrangements, intimate garden corners, vine-covered doorways, and pathways bursting with colorful blooms. These works epitomize his mature Impressionist style.

Living in Kennebunkport allowed Graves to observe and depict the local character and environment authentically. Beyond the celebrated garden scenes, his canvases sometimes captured aspects of New England rural and coastal life, featuring figures like farmers, fishermen, and weathered sea captains. These genre scenes, rendered with the same attention to light and atmosphere as his floral works, provide a glimpse into the regional identity of coastal Maine during that era. His deep connection to Kennebunkport is evident in the sheer volume of work inspired by its surroundings.

Artistic Style: Impressionism with a Decorative Flair

Abbott Fuller Graves is best classified as an American Impressionist, yet his style possesses distinct characteristics that set it apart. Deeply influenced by his time in France and his association with artists like Hassam, Graves embraced the core tenets of Impressionism: the use of vibrant, often unmixed colors, broken brushwork (impasto) to create texture and capture the scintillating effects of light, and a commitment to painting en plein air (outdoors) or simulating the effects of natural light in his studio work.

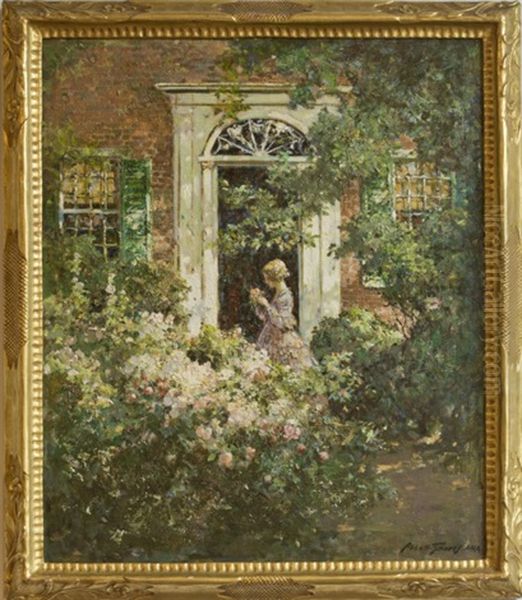

His primary focus on gardens and flowers distinguishes him. Unlike some Impressionists who explored urban scenes or broader landscapes, Graves specialized in the intimate beauty of the cultivated garden. His compositions often feature close-up views of flowerbeds, garden paths, pergolas draped in blossoms, and sunlit doorways framed by climbing roses or other flowering vines. He excelled at capturing the lushness and abundance of these settings, using thick strokes of paint to convey the texture of petals, leaves, and stone pathways. Light was paramount; his paintings shimmer with the effects of sunlight filtering through leaves or illuminating blossoms with intense color.

While Impressionistic in technique, Graves's work often carries a strong decorative quality. His arrangements of flowers, whether in a garden setting or a still life vase, are carefully composed for visual appeal, emphasizing harmony of color and form. This decorative sensibility made his work highly popular among collectors seeking beautiful, uplifting imagery for their homes. His paintings often evoke a sense of tranquility, nostalgia, and idealized beauty, celebrating the simple pleasures of nature and domestic life. This sometimes led to his work being perceived as less edgy than that of some European or even American contemporaries like Robert Henri or John Sloan, who focused on grittier urban realism, but it secured his niche as a master of the garden genre.

Interest in Colonial Revival Architecture

Beyond his celebrated floral and garden paintings, Abbott Fuller Graves nurtured a distinct interest in architecture, particularly the Colonial Revival style that gained popularity in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. This interest likely stemmed from his early, albeit brief, architectural studies at MIT, but it found artistic expression later in his career. He became known for painting "portraits" of Colonial Revival homes, capturing not just their physical structure but also their historical resonance and aesthetic charm.

These architectural paintings often depicted stately homes nestled within well-kept gardens or landscapes, seamlessly blending his interest in structures with his love for natural settings. He rendered these houses with attention to detail, highlighting characteristic features of the Colonial Revival style, such as symmetrical facades, gabled roofs, and classical porticos. Yet, he approached these subjects with his Impressionist sensibility, using light and color to convey atmosphere and integrate the buildings harmoniously with their surroundings.

These works served not only as artistic creations but also as historical documents of a sort, preserving the appearance of significant regional architecture. They reflected a broader cultural interest in America's colonial past during a period of rapid industrialization and change. For Graves, these house portraits represented another facet of New England's identity, complementing his depictions of its gardens and people. This thematic diversity adds another layer to his artistic contributions.

Representative Works

While Graves produced a prolific number of paintings, certain works stand out as representative of his style and preferred subjects. Though specific titles frequently recurred with variations, themes centered on gardens and floral arrangements dominate his known oeuvre.

Garden Scenes: Paintings titled In the Garden, Doorway Garden, Garden Path, A Kennebunkport Garden, or similar variations are central to his legacy. These works typically showcase lush, sunlit gardens, often featuring architectural elements like doorways, gates, or pergolas adorned with climbing flowers. Figures, usually elegantly dressed women, sometimes appear, interacting subtly with the garden environment, perhaps reading or tending flowers. The emphasis is consistently on the vibrant color, textured foliage, and the play of light and shadow.

Floral Still Lifes: Graves was also a master of the floral still life. Works like Mixed Bouquet of Roses (a title he revisited) exemplify his skill in this genre. These paintings often depict abundant bouquets arranged in vases, bowls, or baskets. He captured the delicate textures of petals and leaves with rich impasto, contrasting the vibrant hues of the flowers against simpler backgrounds. His still lifes, like his garden scenes, are characterized by their decorative quality and celebration of natural beauty.

These representative themes highlight Graves's consistent focus and his ability to infuse Impressionist techniques with a personal vision centered on the beauty of the cultivated and natural world, particularly flowers. His dedication to these subjects earned him the informal title of one of America's premier "garden painters."

Relationships with Contemporary Artists

Abbott Fuller Graves's artistic journey was significantly shaped by his interactions with contemporary painters, both through collaboration and friendly competition. His relationships with key figures of the American Impressionist movement, particularly those associated with the Boston School, were pivotal.

His most enduring artistic friendship was arguably with Edmund C. Tarbell (1862-1938). From their student days at the Museum School in Boston to their shared experiences studying and living together in Paris in 1884, Tarbell was a constant presence in Graves's early career. They shared influences and likely engaged in frequent discussions about technique and style. While Tarbell became more known for his elegant interior figure paintings, their shared grounding in academic training and subsequent embrace of Impressionism formed a strong bond.

Frederick Childe Hassam (1859-1935), born in the same year as Graves, was another crucial connection. Their friendship, solidified during Graves's time in Paris and continued during their overlapping teaching stints at the Cowles Art School, was highly influential. Hassam was a leading proponent of American Impressionism, and his vibrant, light-filled canvases undoubtedly encouraged Graves's own explorations in the style. While they remained friends, their career paths diverged somewhat; Hassam achieved national prominence based largely in New York, becoming one of the "Ten American Painters," while Graves found his niche more firmly rooted in New England, particularly Maine. This divergence might imply a subtle element of competition or simply different artistic and personal priorities.

In Paris, Graves studied under Georges Jeannin (1841-1925), a specialist in flower painting, whose technical guidance was directly relevant to Graves's later specialization. He was also exposed to the broader currents of French art, including the work of academic painters like Jean-Paul Laurens (though Laurens's historical subjects were far removed from Graves's focus) and, more importantly, the leading French Impressionists like Claude Monet (1840-1926), Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-1919), and Camille Pissarro (1830-1903), whose innovations fundamentally altered the course of Western art.

Within the Boston context, Graves operated alongside other prominent figures of the Boston School, such as Frank Weston Benson (1862-1951) and Joseph DeCamp (1858-1923). While their primary focus often differed (Benson and Tarbell were famed for figurative work, DeCamp for portraits), they shared a common milieu, exhibiting together and contributing to Boston's reputation as an art center. Graves also moved in wider circles of American Impressionism, contemporary to artists like John Henry Twachtman (1853-1902), J. Alden Weir (1852-1919), Theodore Robinson (1852-1896), and Willard Metcalf (1858-1925), all of whom adapted Impressionism to American landscapes and sensibilities. Even the towering figure of John Singer Sargent (1856-1925), though distinct in style, was a contemporary whose work resonated within the Boston art scene. These connections place Graves firmly within the dynamic network of artists shaping American Impressionism.

Exhibitions, Recognition, and Memberships

Throughout his career, Abbott Fuller Graves actively participated in the art world through exhibitions and memberships in prestigious organizations, gaining recognition both regionally and nationally. His work was showcased in numerous important venues, contributing to his reputation and the dissemination of his style.

He exhibited regularly at the Boston Art Club, starting early in his career. His work was also shown at major national institutions, including the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia and the Art Institute of Chicago, two of the most important venues for American artists at the time. His participation in these exhibitions placed his work alongside that of the leading artists of the day.

Graves achieved significant recognition from the National Academy of Design in New York, a bastion of the American art establishment. He was elected an Associate Member (ANA) in 1926, a mark of distinction acknowledging his contributions to American art. He also exhibited his work at the Academy's annual exhibitions.

His European training and connections were reflected in his participation in the Paris Salon, the official art exhibition of the Académie des Beaux-Arts in Paris. Exhibiting at the Salon was a major goal for many American artists seeking international validation, and Graves not only showed his work there but reportedly received an award, further bolstering his credentials.

In addition to these major institutions, Graves was affiliated with several artist societies. He was a member of the Salmagundi Club in New York City, one of the oldest art clubs in the United States, known for its camaraderie and exhibitions. He was also a member of the Allied Artists of America. Locally, he was involved with art activities in Maine, and sources mention him as an annual exhibitor at the "Polish Spring Art Exhibition," likely referring to Poland Spring, Maine, known for its resort and associated art exhibitions. His work found its way into numerous galleries in Boston, New York, and Maine throughout his career.

Later Life, Legacy, and Collections

Abbott Fuller Graves continued to paint actively throughout the early decades of the 20th century. He remained largely based in Kennebunkport, Maine, drawing inspiration from its gardens and coastal environment. His Impressionist style, focused on beauty and light, remained popular with a segment of the public even as Modernist movements like Cubism and Fauvism began to challenge traditional aesthetics. While some critics might have found his work increasingly idealized or nostalgic compared to the avant-garde, his paintings retained their appeal for their decorative qualities and technical skill.

His dedication to his craft was recognized through his election as an Associate of the National Academy of Design in 1926. He continued to exhibit his work in galleries, maintaining a presence in the art market. His dual life, maintaining connections in both the Boston/New York art scenes and the quieter community of Kennebunkport, characterized his later years.

Abbott Fuller Graves passed away on July 15, 1936, in Kennebunkport, the town that had been his home and primary source of inspiration for over four decades. He left behind a significant legacy as a key figure in American Impressionism, particularly renowned for his specialization in garden scenes and floral paintings. His work captured a specific aspect of American life and landscape during a period of transition, celebrating natural beauty with a distinctive blend of Impressionist technique and decorative sensibility.

Today, Graves's paintings are held in the permanent collections of numerous museums and institutions, attesting to his enduring importance. These include the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the Arnot Art Museum in Elmira, New York, the Brick Store Museum in Kennebunk, Maine (which holds significant local history), and the Princeton University Art Museum, among others. His works also remain popular in private collections and frequently appear at auction, continuing to be appreciated for their vibrant beauty and skillful execution. He remains an important representative of New England Impressionism and a master of the American garden painting genre.