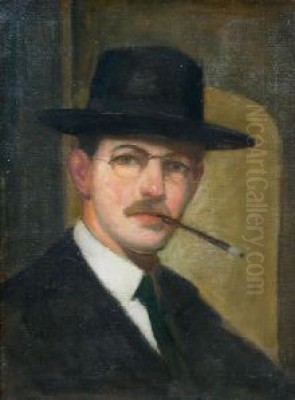

Richard Edward Miller stands as a significant figure in the story of American Impressionism, an artist celebrated for his elegant depictions of women, his sophisticated understanding of color, and his masterful handling of light. Born in St. Louis, Missouri, on March 22, 1875, and passing away on January 23, 1943, Miller's career bridged the artistic worlds of the American Midwest, the vibrant art scene of Paris, and the influential artist colony in Giverny. His work, characterized by serene beauty and technical brilliance, continues to captivate audiences and holds an important place in the narrative of American art at the turn of the twentieth century.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Richard E. Miller's journey into the world of art began in his hometown of St. Louis. Displaying a clear aptitude and passion for drawing from a young age, he made the decisive choice to pursue art professionally by the age of ten. This early commitment set the stage for his formal training. He enrolled at the St. Louis School of Fine Arts (now part of Washington University), where he studied for five years, honing his foundational skills in drawing and painting. During his time there, he also gained practical experience working as an illustrator for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, developing a keen eye for observation and narrative composition that would subtly inform his later easel painting. His talent was evident, earning him recognition and laying the groundwork for the next crucial phase of his development.

Parisian Training and Early Success

Like many ambitious American artists of his generation, Miller looked towards Paris, the undisputed center of the art world, to further his education and career. In 1898, having secured a scholarship, he traveled to France and enrolled in the prestigious Académie Julian. This renowned private art school offered a more liberal alternative to the official École des Beaux-Arts and attracted students from across the globe. In Paris, Miller studied under prominent academic painters Jean-Paul Laurens and Benjamin Constant, artists known for their historical subjects and portraiture. This rigorous training provided him with a strong command of draughtsmanship and traditional techniques.

Miller quickly absorbed the stimulating atmosphere of Paris. He began exhibiting his work, achieving early success when one of his portraits was accepted into the famed Paris Salon, the official art exhibition sponsored by the French government. This was a significant accomplishment for a young foreign artist, signaling his arrival on the competitive Parisian art scene. While his initial training was rooted in academic tradition, the air in Paris was thick with newer, more revolutionary ideas, particularly the lingering influence and ongoing evolution of Impressionism, pioneered by artists like Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Edgar Degas, and Camille Pissarro just a couple of decades earlier.

The Giverny Years: Embracing Impressionism

A pivotal moment in Miller's artistic evolution occurred around 1905 when he moved to the village of Giverny in Normandy. This picturesque location had become famous as the home of Claude Monet, the leading figure of Impressionism. Drawn by the presence of the master and the beautiful French countryside, a vibrant colony of American artists had established itself there. Miller became a key member of this "Giverny Group," immersing himself in the Impressionist ethos that permeated the village.

Living and working in close proximity to Monet's celebrated gardens, Miller's style underwent a profound transformation. He moved away from the darker palettes and tighter brushwork potentially associated with his academic training or early tonalist leanings. Influenced directly by the light-filled canvases of Monet and the general atmosphere of plein air painting prevalent in Giverny, Miller embraced a brighter, more vibrant color scheme. His brushwork became looser and more expressive, capturing the fleeting effects of sunlight and atmosphere. This period marked his full commitment to the Impressionist style, albeit interpreted through his own distinct sensibility.

Friendship and Artistic Dialogue: Miller and Frieseke

In Giverny, Miller formed a close association with fellow American painter Frederick Carl Frieseke. For a time, they were neighbors, sharing the artistic and social life of the expatriate community. Both artists focused on similar themes – predominantly women in sunlit interiors or gardens – and both adopted a high-keyed palette and broken brushwork characteristic of Impressionism. They, along with other Giverny artists like Guy Rose, Lawton Parker, and Edmund Greacen, formed a core group exploring Impressionist ideas within an American context.

Despite their shared environment and subject matter, subtle but important distinctions existed between Miller's and Frieseke's work, as noted by later art historians like William H. Gerdts. While both excelled at depicting light and feminine grace, Gerdts observed that Miller often retained a stronger emphasis on drawing and underlying structure within his compositions. Frieseke, perhaps, pushed further towards decorative surfaces, and his figures sometimes possessed a different kind of charm, described by Gerdts as more "piquant and lovely," potentially less influenced by the specific classicism found in Renoir compared to Miller. This friendly dialogue and subtle competition likely spurred both artists creatively during their Giverny years.

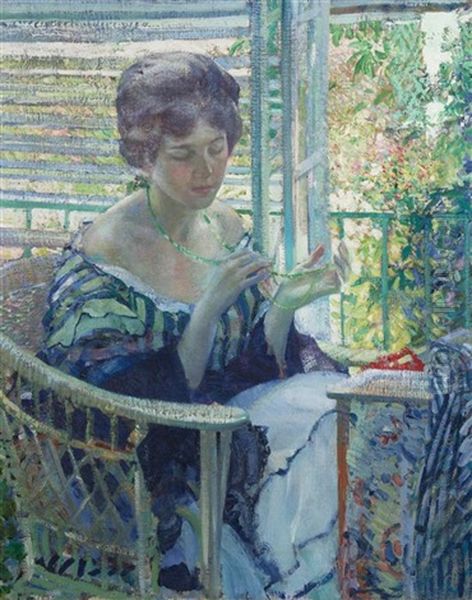

Signature Themes: The Elegance of Modern Womanhood

Richard E. Miller is perhaps best known for his captivating paintings of women. His canvases typically feature elegantly dressed female figures absorbed in quiet, everyday moments: reading a book, sewing, arranging flowers, lost in thought before a mirror, or enjoying tea. These scenes often unfold in beautifully appointed domestic interiors, flooded with natural light from a window, or outdoors in sun-dappled gardens. Works like The Necklace, Afternoon Tea, Woman in Sunlight, and Woman Before a Mirror exemplify his focus on this theme.

Miller's approach was not merely illustrative; he imbued his subjects with a sense of serenity, introspection, and quiet grace. He captured the textures of luxurious fabrics, the warmth of sunlight on skin, and the intimate atmosphere of private life. His women are presented as figures of modern femininity – poised, contemplative, and occupying spaces defined by beauty and tranquility. Through these works, Miller explored the interplay of light, color, and form, using the female figure as a vehicle for his artistic investigations into the ephemeral beauty of the visual world.

Technique and Style: Mastering Light and Color

Miller's mature style is a testament to his mastery of Impressionist techniques, adapted to his own artistic vision. His palette became characteristically bright and luminous, employing harmonious combinations of colors to render the effects of light. He was particularly adept at capturing dappled sunlight filtering through leaves or windows, creating intricate patterns of light and shadow that animate his compositions. His brushwork, while generally loose and suggestive in the Impressionist manner, could vary; sometimes fluid and energetic, other times more controlled to define form or texture.

His compositions often display a strong decorative sense, balancing figures, furniture, fabrics, and floral elements into pleasing arrangements. This decorative quality might reflect an awareness of contemporary trends in French art, such as the work of the Nabis painters like Pierre Bonnard and Édouard Vuillard, who emphasized pattern and flattened space, or the pervasive influence of Japanese prints on Western artists. Miller skillfully integrated these elements while maintaining a sense of realism and volume in his figures. He achieved a unique synthesis, blending the Impressionist concern for light and atmosphere with a solid grounding in drawing and a distinctively American sensibility for clarity and structure.

Beyond Giverny: Later Career and Teaching

With the outbreak of World War I, the idyllic era in Giverny came to an end for many American artists. Miller eventually returned to the United States. While he continued to paint and exhibit, his later career saw shifts in location and focus. From 1915 to 1917, he brought his expertise to California, teaching painting at the Stickney Memorial School of Art in Pasadena. This period exposed him to a different quality of light and landscape, potentially influencing his work.

Some art historians, including William Gerdts, have suggested that Miller's work in his later years occasionally took on a darker tonality and perhaps more somber themes compared to the high-keyed brilliance of his Giverny period. This evolution might reflect personal changes, a response to the changing artistic landscape as Modernism gained ground, or simply a natural development in his artistic exploration. Regardless of these shifts, his reputation as a leading figure painter remained strong. His earlier work as an illustrator for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch also remained part of his professional history, showcasing the breadth of his artistic skills from the outset.

Recognition and Market Success

Richard E. Miller achieved considerable recognition both during his lifetime and posthumously. His successes began early with his acceptance into the Paris Salon and continued throughout his career. He received numerous awards and honors for his work in exhibitions both in the United States and internationally, including accolades in France and Italy. His paintings were sought after by collectors and acquired by major public institutions, securing his place within the canon of American art.

His ability to navigate the art market was also a factor in his success. During his time in Paris and Giverny, he established relationships with dealers and galleries, ensuring his work reached an appreciative audience. Like the original French Impressionists who relied on dealers such as Paul Durand-Ruel to champion their work against initial academic resistance, Miller and his American contemporaries also benefited from a growing gallery system and collector base interested in Impressionism. He was an active member of various art clubs, further integrating him into the professional art community of his time.

Legacy and Art Historical Significance

Richard E. Miller's legacy rests on his significant contribution to American Impressionism. He is considered one of the foremost members of the "Giverny Group," American artists who adapted French Impressionist principles to their own cultural context and artistic temperaments. His unique achievement lies in the synthesis he forged: combining the rigorous drawing and compositional structure learned through his academic training with the vibrant color, light sensitivity, and modern subject matter of Impressionism. He absorbed the lessons of masters like Monet and Renoir, but translated them into a personal style marked by elegance, serenity, and technical refinement.

While an early source mistakenly suggested he influenced artists like Degas and Pissarro (the influence clearly flowed from these pioneers to Miller's generation), Miller's true impact was within the realm of American art. He, alongside contemporaries like Frederick Frieseke, Childe Hassam, Mary Cassatt (though she was an earlier expatriate figure), and others who embraced Impressionism, helped shape a distinctly American chapter of this international movement. His paintings, particularly his luminous depictions of women in interiors and gardens, remain highly regarded for their beauty, emotional resonance, and masterful technique. His works are held in the collections of numerous important museums, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the Art Institute of Chicago, ensuring his art continues to be studied and admired.

Conclusion

Richard Edward Miller carved a distinguished path as an American Impressionist painter. From his early training in St. Louis to his formative years in Paris and his flourishing career centered around Giverny, he dedicated himself to capturing beauty, particularly the elegance of women and the transient effects of light. His sophisticated use of color, confident brushwork, and serene compositions earned him international acclaim. He remains celebrated for his ability to blend American artistic sensibilities with the innovations of French Impressionism, leaving behind a body of work that continues to enchant viewers with its timeless grace and luminous artistry, securing his enduring importance in American art history.