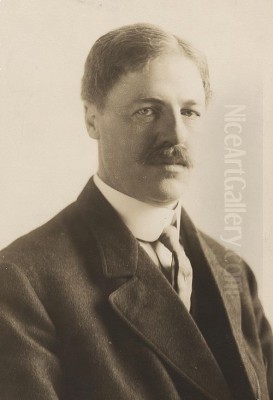

Frank Weston Benson (1862-1951) stands as a pivotal figure in the story of American art at the turn of the twentieth century. A leading member of the American Impressionist movement, Benson skillfully blended the vibrant light and color techniques learned from French masters with a distinctly American sensibility. His canvases often celebrate the idyllic aspects of family life, the beauty of the New England landscape, and the dynamic energy of the natural world. As a founding member of the influential group known as "The Ten American Painters" and a long-serving, respected educator, Benson left an indelible mark on the generation of artists who followed him.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born in the historic maritime city of Salem, Massachusetts, in 1862, Frank W. Benson emerged from a background that appreciated culture and the outdoors. His initial artistic inclinations led him, in 1880, to enroll at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts (SMFA) in Boston. This institution was relatively new but rapidly gaining importance as a center for artistic training in America.

At the SMFA, Benson studied under the German-born artist Otto Grundmann, one of the school's founding figures. Grundmann instilled in his students a respect for solid draftsmanship and the academic traditions of European art. It was also during this formative period in Boston that Benson forged a lifelong friendship with fellow student Edmund C. Tarbell. Their shared artistic ambitions and mutual respect would significantly shape both their careers and the direction of painting in Boston.

Seeking to broaden his artistic horizons, Benson, like many ambitious American artists of his generation, traveled to Paris in 1883. He enrolled at the prestigious Académie Julian, a popular choice for foreign students seeking an alternative to the rigid École des Beaux-Arts. There, he studied under the tutelage of prominent academic painters Gustave Boulanger and Jules Joseph Lefebvre, further honing his skills in figure drawing and composition according to established French academic standards. His time in Paris exposed him not only to rigorous academic training but also to the revolutionary currents of Impressionism that were transforming the European art world, even if his formal instruction remained traditional.

Return to Boston and Early Career

Upon returning from Paris in the mid-1880s, Benson began to establish his professional career. He initially taught art in Portland, Maine, before securing a position back at his alma mater, the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, in 1889. He would remain associated with the SMFA for decades, eventually becoming the head of the Painting Department alongside his friend Edmund Tarbell, who led the advanced painting classes. Their combined influence would be instrumental in shaping what became known as the "Boston School" of painting.

Benson quickly gained recognition for his technical skill and refined aesthetic. His early works often included portraits and interior scenes, executed with the polished finish and attention to detail favored by his academic training. However, the influence of Impressionism, particularly its emphasis on light and atmosphere, began to subtly permeate his work.

His talent did not go unnoticed in the wider art world. In 1890, he received his first major accolade, the prestigious Hallgarten Prize from the National Academy of Design in New York. This was followed by a medal at the World's Columbian Exposition held in Chicago in 1893, a major international event that showcased American artistic and industrial achievement. These early successes helped solidify his reputation as a rising star in American art.

Impressionism, Boston Style

While Benson absorbed the lessons of French Impressionism, particularly the work of artists like Claude Monet in capturing the effects of light, he and his Boston colleagues developed a distinct regional interpretation of the style. Benson, along with Edmund Tarbell, became leading exponents of the "Boston School." This approach sought to harmonize the vibrant palette, broken brushwork, and plein-air (outdoor) sensibility of Impressionism with the solid draftsmanship, formal composition, and often elegant subject matter rooted in their academic training.

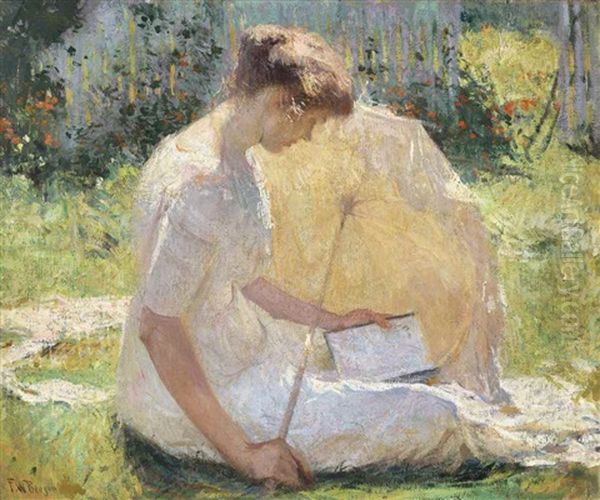

Unlike some of the French Impressionists who dissolved form completely into light and color, Benson and Tarbell often retained a strong sense of structure and realism, particularly in their figure painting. Their work frequently depicted refined women and children in sunlit interiors or tranquil outdoor settings, conveying a sense of genteel domesticity and quiet beauty. Benson became particularly adept at rendering the play of sunlight on figures and fabrics, using a bright, optimistic palette.

His commitment to capturing natural light often led him to paint outdoors, or en plein air. This practice was central to the Impressionist ethos, allowing artists to directly observe and translate the fleeting effects of light and atmosphere onto the canvas. Benson's numerous paintings set in the open air are testaments to his mastery of this approach, showcasing his ability to convey the warmth of sunlight, the coolness of shadows, and the gentle breezes of a summer day.

The Ten American Painters

By the late 1890s, Benson, Tarbell, and several other like-minded artists grew dissatisfied with the large, juried exhibitions held by established organizations like the Society of American Artists (SAA) and the National Academy of Design (NAD). They felt these sprawling shows were often overcrowded and did not provide an ideal setting for viewing their more intimate, Impressionist-influenced works.

In response, Benson and Tarbell, along with J. Alden Weir and John Henry Twachtman (though Twachtman died before the group fully coalesced and was effectively replaced), initiated a secession from the SAA in 1897. They formed a new exhibiting group known simply as "The Ten American Painters," or "The Ten." The founding members included Benson, Tarbell, Weir, Twachtman (initially), Childe Hassam, Willard Metcalf, Robert Reid, Edward Simmons, Thomas Dewing, and Joseph DeCamp. After Twachtman's death, William Merritt Chase briefly took his place in exhibitions.

The Ten aimed to present their work in smaller, more harmonious exhibitions where their paintings could be seen to better advantage. They held annual shows, primarily in New York but also occasionally in Boston and other cities, for about twenty years. Benson was a core member throughout the group's existence. The Ten became synonymous with American Impressionism and played a crucial role in promoting the style and gaining wider acceptance for it within the United States. Their exhibitions were generally well-received critically and commercially, solidifying the reputations of the individual members, including Benson.

Golden Summers: Family and Light

Perhaps Benson's most celebrated and characteristic works emerged during the height of his Impressionist period, roughly from the late 1890s through the 1910s. During these years, he frequently depicted his own wife, Ellen Perry Benson, and their children – daughters Eleanor, Elisabeth, and Sylvia, and son George – enjoying leisurely summer days. His primary setting for these idyllic scenes was Wooster Farm, the family's summer retreat on North Haven Island in Maine's Penobscot Bay.

Paintings such as Sunlight (1909), Summer (1909), My Little Girl (1912), Two Little Girls (1903), and Red and Gold (1915) exemplify this phase of his work. These canvases are bathed in brilliant sunshine, rendered with a high-keyed palette and lively, broken brushstrokes. Benson masterfully captured the dazzling effects of light filtering through leaves, reflecting off water, or illuminating figures dressed in white summer attire against lush green backgrounds or sparkling blue seascapes.

These works convey an atmosphere of warmth, intimacy, and idealized American family life. While rooted in direct observation, they often possess a decorative quality, emphasizing harmonious arrangements of form and color. The figures, typically his daughters, are portrayed with affection yet often serve as elements within a larger composition focused on the interplay of light, color, and atmosphere. These paintings cemented Benson's reputation as America's "Painter of Sunshine" and remain among his most beloved works. His focus on women and children in domestic or natural settings invites comparison with the work of fellow American Impressionist Mary Cassatt, though Benson's approach often emphasized the outdoor environment more explicitly.

A Shift in Focus: Wildlife and New Media

Around 1912, coinciding with his resignation from full-time teaching at the SMFA (though he continued to advise), Benson began to shift his artistic focus. While he never entirely abandoned Impressionist figure painting, he increasingly turned his attention to wildlife subjects, particularly birds, and explored different artistic media, notably etching, drypoint, and watercolor. This change reflected his lifelong passion for the outdoors, hunting, and fishing.

His etchings and drypoints, often depicting waterfowl in flight or resting on water, quickly gained immense popularity and critical acclaim. He demonstrated remarkable skill in capturing the movement and anatomical accuracy of birds, combined with a strong sense of design and atmospheric effect. These prints found a wide audience among sportsmen and art collectors alike, becoming highly sought after. Works from this period showcase his keen observational skills honed through years spent in nature.

Simultaneously, Benson embraced watercolor with enthusiasm. His watercolors, often created during his summers in Maine or on sporting excursions, possess a fluidity and spontaneity well-suited to capturing the transient effects of weather and light on the landscape and wildlife. Works like Wooster Farm (1924) demonstrate his command of this medium, using transparent washes and bold compositions to convey the essence of the scene. While some critics occasionally found his print production overly prolific or commercial, his mastery across oil, watercolor, and printmaking techniques was widely acknowledged. His dedication to depicting American wildlife connects him to a tradition stretching back to John James Audubon and echoed in the later outdoor scenes of Winslow Homer.

A Respected Educator

Beyond his own artistic production, Frank W. Benson exerted considerable influence as an educator. His long tenure at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, spanning from 1889 until his resignation from full-time duties in 1912 (though he remained a visiting instructor and advisor for years after), shaped a generation of artists. Alongside his close colleague Edmund C. Tarbell, Benson was a central figure in the Painting Department.

Their teaching emphasized the principles that defined the Boston School: rigorous academic drawing combined with an Impressionist sensitivity to light and color. They encouraged students to develop strong technical foundations while also observing the world around them with fresh eyes. Benson was known for his insightful critiques and his ability to nurture individual talent.

The list of artists who studied under Benson and Tarbell includes many who went on to achieve significant recognition, contributing to the ongoing legacy of the Boston School aesthetic well into the 20th century. While specific names like Robert Levis and others are sometimes mentioned, his broader impact lay in establishing a pedagogical approach that valued both tradition and direct observation, influencing figures associated with the Boston School such as Philip Leslie Hale (who also taught at the SMFA) and numerous students who carried these principles into their own careers. His role as a teacher cemented his position as a leader within the Boston art community.

Accolades and Enduring Legacy

Throughout his long and productive career, Frank W. Benson received numerous honors and awards, reflecting the high esteem in which he was held. Following his early successes with the Hallgarten Prize (1890) and the Chicago World's Fair medal (1893), he continued to garner recognition. Notable awards included the Shaw Prize (or possibly the Shorter Medal, as noted in some sources) from the Society of American Artists in 1902, and both the W.A. Clark Prize and the prestigious Corcoran Gold Medal from the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington D.C. in 1912.

He was elected an Associate of the National Academy of Design in 1897, the same year The Ten was formed, and became a full Academician in 1905. His prominence was further confirmed by major retrospective exhibitions of his work, including significant shows held at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in 1912 and again in 1941. His participation in the landmark Armory Show of 1913, though representing the more established wing of American art against the tide of European modernism championed by figures like Alfred Stieglitz, demonstrated his continued relevance in the national art scene.

Today, Benson's works are held in the permanent collections of major American museums, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the Art Institute of Chicago, the National Gallery of Art, the Corcoran Collection (now part of the National Gallery), and the Library of Congress, among many others. His paintings, particularly the sun-drenched depictions of his family, remain icons of American Impressionism, celebrated for their beauty, technical brilliance, and evocation of a specific time and place in American life.

Conclusion

Frank Weston Benson carved a unique and enduring path in American art history. He successfully navigated the transition from 19th-century academicism to 20th-century Impressionism, creating a style that was both sophisticated and accessible. As a key member of The Ten American Painters and a leader of the Boston School, he helped shape the course of American Impressionism, championing a vision that balanced painterly freedom with formal structure.

His legacy rests not only on his luminous paintings of family life under the New England sun but also on his masterful wildlife prints and watercolors, which captured his deep connection to the natural world. Furthermore, his decades as an influential teacher ensured that his artistic principles would resonate through subsequent generations. Frank W. Benson remains a celebrated figure, admired for his technical virtuosity, his sensitivity to light and color, and his quintessential depictions of American life at the turn of the century.