Abraham Bosse stands as a significant, if sometimes controversial, figure in the landscape of 17th-century French art. A master etcher, influential theorist, and keen observer of his times, Bosse's prolific output provides an invaluable window into the social customs, intellectual currents, and artistic practices of the French Baroque era. His life and career were marked by technical innovation, pedagogical ambition, and a staunch adherence to principles that often brought him into conflict with the burgeoning academic establishment.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Tours and Paris

Born around 1602 or 1604 in Tours, France, Abraham Bosse's early life was shaped by the religious and social fabric of this provincial city. His father, Louis Bosse, was a tailor of German origin, and his mother, Marie Martinet, was also from Tours. Crucially, the Bosse family were Huguenots, French Calvinist Protestants, a religious minority in a predominantly Catholic France. This religious identity would subtly, and sometimes overtly, inform his worldview and aspects of his artistic output, particularly in a period marked by religious tensions following the Edict of Nantes and its eventual revocation.

Little is definitively known about Bosse's earliest artistic training in Tours. However, the city was not without its artistic resources, and it's likely he received initial instruction in drawing and perhaps the rudiments of engraving there. By the 1620s, Bosse had made the pivotal move to Paris, the vibrant artistic and cultural heart of France. This relocation was essential for any artist with serious ambitions, offering access to patrons, fellow artists, and the latest stylistic developments.

In Paris, Bosse encountered the work of Jacques Callot, the renowned etcher from Lorraine, who was active in the city between 1629 and 1631. Callot's innovative etching techniques, his lively and detailed depictions of contemporary life, military scenes, and theatrical performances, undoubtedly made a strong impression on the young Bosse. While not a direct pupil in a formal master-apprentice sense, Bosse absorbed Callot's influence, particularly in the clarity of line and the meticulous rendering of detail. He also became associated with the print publisher Melchior Tavernier, a Flemish engraver and print-seller active in Paris, who began publishing Bosse's works around 1629 and would continue to do so for many years, playing a crucial role in disseminating his art.

Another profoundly important influence, and one that would shape Bosse's entire theoretical outlook, was his encounter with the work and ideas of Girard Desargues (1591-1661). Desargues was a brilliant mathematician and engineer from Lyon, a pioneer in projective geometry. His theories on perspective offered a more universal and mathematically rigorous system than many of the empirical methods then in use. Bosse became a fervent admirer and popularizer of Desargues's complex geometrical principles, translating them into practical applications for artists. This intellectual alignment would become a cornerstone of Bosse's teaching and writings, and also a source of future conflict.

The Prolific Engraver: A Mirror to Society

Abraham Bosse was, above all, a master of the etching needle and burin. His oeuvre comprises over 1600 prints, a remarkable testament to his industry and skill. He worked primarily in etching, often refining his plates with the burin to achieve a clarity and precision that led some to describe his style as "etching that looks like engraving." This meticulous approach lent itself well to the detailed depiction of his chosen subjects.

Bosse's subject matter was extraordinarily diverse, reflecting the multifaceted nature of 17th-century French life. He produced genre scenes depicting the everyday activities of various social classes, from elegant aristocrats in lavish interiors to artisans in their workshops and peasants in more rustic settings. These prints are invaluable historical documents, meticulously recording the fashions, furnishings, social etiquette, and occupations of the period. Series like Le Jardin de la Noblesse Française (The Garden of French Nobility) or Les Métiers (The Trades) offer rich visual information.

Religious subjects also formed a significant part of his output. As a Huguenot, Bosse's approach to biblical scenes often carried a particular character. He frequently depicted these sacred narratives using contemporary dress and settings, a practice that, while not unique to him, served to make the stories more immediate and relatable to his audience. This can be seen in works like his illustrations for the "History of the Prodigal Son" or "The Wise and Foolish Virgins." His religious prints often emphasized moral instruction and piety, consistent with Calvinist values.

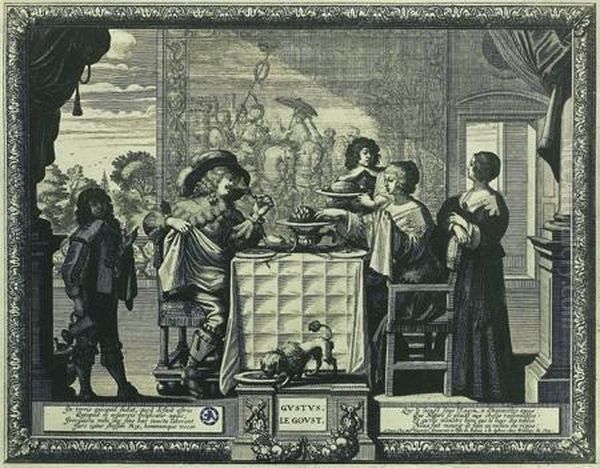

Allegorical and symbolic representations were another forte. Bosse created complex allegories on themes such as the ages of man, the seasons, the senses, and the virtues and vices. These prints often drew on established iconographic traditions but were rendered with his characteristic clarity and attention to contemporary detail, making them accessible while still conveying sophisticated moral or philosophical messages.

He also produced portraits, book illustrations, and prints related to significant historical events. His ability to capture the likeness of individuals, combined with his skill in depicting intricate settings, made him a sought-after illustrator. His prints often served as frontispieces or illustrations for scientific treatises, literary works, and theological texts, demonstrating the versatility of his art.

Masterpieces of the Etching Needle

Among Bosse's vast output, several works and series stand out for their artistic quality, historical significance, or thematic importance.

Le Mariage à la Ville (The City Wedding) and Le Mariage à la Campagne (The Country Wedding), both from around 1633, are excellent examples of his genre scenes. These prints meticulously detail the customs, attire, and social interactions associated with weddings among different social strata. The former depicts an elegant urban ceremony, while the latter portrays a more rustic, boisterous celebration, offering a comparative glimpse into societal norms.

Les Gardes Françaises (The French Guards), a series depicting soldiers, showcases his ability to render military attire and bearing with precision. These prints were popular and contributed to the visual culture surrounding the French military during the reign of Louis XIII.

One of his most famous series is Les Cinq Sens (The Five Senses), created around 1635-1638. Each print personifies one of the senses – Sight, Hearing, Smell, Taste, and Touch – through elegantly dressed figures in richly appointed interiors, engaged in activities related to that sense. These works are celebrated for their exquisite detail, refined compositions, and the way they capture the luxurious ambiance of affluent 17th-century life.

L'Hôpital de la Charité (The Charity Hospital, c. 1636-1640) is a poignant depiction of a ward in a charitable institution, showing nuns caring for the sick. It reflects the era's concerns with piety and social welfare, rendered with a compassionate eye for detail.

His illustrations for Jean Desmarets de Saint-Sorlin's epic poem Clovis (1657) are notable examples of his work as a book illustrator, demonstrating his ability to translate literary narratives into compelling visual form.

Perhaps one of his most ambitious historical prints is The Entry of Queen Christina of Sweden into Paris (although the exact title and attribution can vary, he did works related to significant entries). Such prints captured important contemporary events, serving a role akin to visual news reporting for a wider public.

His series on The Parable of the Prodigal Son and The Wise and Foolish Virgins (e.g., Les Vierges Folles et les Vierges Prudentes, c. 1635) are significant religious works. The Foolish Virgins (1664), in particular, is a powerful moral allegory, executed with his characteristic precision and often interpreted through the lens of his Huguenot faith, emphasizing preparedness and spiritual diligence.

The Wedding of Ladislaus IV of Poland and Louise Marie Gonzaga (1645) is another example of a print commemorating a significant contemporary event, showcasing his skill in handling complex group compositions and ceremonial detail.

These examples represent only a fraction of his output but illustrate the breadth of his subjects and the consistent quality of his execution. His prints were widely circulated and admired, influencing other engravers and providing a rich visual record for subsequent generations.

The Theorist and Educator: Champion of Desarguesian Perspective

Abraham Bosse was not content merely to practice his art; he was also a dedicated theorist and educator, passionate about establishing a rational and systematic basis for artistic practice, particularly in the realm of perspective. His most significant contribution in this area was his advocacy and popularization of the perspective theories of Girard Desargues.

Desargues's work on projective geometry, while groundbreaking, was often abstruse and written in a specialized language that made it inaccessible to many artists. Bosse took it upon himself to translate these complex mathematical concepts into practical rules and methods that artists could understand and apply. He published several influential treatises on the subject, which became standard texts for art education.

His first major theoretical work was La manière universelle de M. Desargues, pour pratiquer la perspective par petit-pied, comme le géométral (1648), which translates to "The Universal Method of Mr. Desargues for Practicing Perspective with a Small Foot, like the Geometrical Plan." This book laid out Desargues's system in a more accessible format, illustrated with numerous diagrams and examples drawn by Bosse himself. He argued for the superiority of this "universal method" over other, often more empirical or less mathematically rigorous, approaches to perspective.

He followed this with other important texts, including Moyen universel de pratiquer la perspective sur les tableaux, ou surfaces irrégulières (1653), addressing perspective on irregular surfaces, and Traité des pratiques géométrales et perspectives, enseignées dans l'Académie Royale de la Peinture et Sculpture (1665), or "Treatise on Geometrical and Perspective Practices, Taught in the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture."

Bosse's treatises were not limited to perspective. In 1645, he published Traicté des manières de graver en taille douce sur l'airin par le moyen des eaux fortes et des vernis durs et mols ("Treatise on the Methods of Engraving in Intaglio on Copper by Means of Strong Acids and Hard and Soft Grounds"). This was one of the earliest comprehensive technical manuals on etching and engraving, detailing the tools, materials, and processes involved in printmaking. It was highly influential and translated into several languages, remaining a key resource for printmakers for many years. Charles-Nicolas Cochin the Younger would later revise and expand this work in the 18th century.

Bosse's commitment to Desarguesian perspective was unwavering, and he saw it as the only truly rational and scientific basis for representation. This conviction, however, would eventually lead to significant conflict within the artistic establishment.

The Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture: A Tumultuous Relationship

In 1648, the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture (Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture) was founded in Paris. This institution, established under royal patronage, aimed to elevate the status of artists from mere craftsmen to practitioners of a liberal art, to provide a structured system of art education, and to establish a canon of artistic excellence. Abraham Bosse was among the founding members of the Academy and was appointed as its first professor of perspective in 1651.

Initially, Bosse's role in the Academy seemed promising. His expertise in perspective and his published treatises made him a natural choice for this teaching position. He diligently lectured on Desargues's methods, seeking to instill these principles in the students. However, his uncompromising adherence to Desarguesian geometry and his often dogmatic and reportedly "irascible" personality soon brought him into conflict with other influential members of the Academy, most notably Charles Le Brun.

Charles Le Brun, a powerful figure who would later become the director of the Academy and Premier Peintre du Roi (First Painter to the King) under Louis XIV, favored a different approach to art education. While not dismissing perspective, Le Brun and his faction emphasized other aspects of artistic training, including the study of classical antiquity, the works of masters like Raphael and Nicolas Poussin, and a more eclectic approach to perspective that did not rigidly adhere to Desargues's system. They found Bosse's insistence on the absolute primacy of Desarguesian geometry to be overly restrictive and perhaps even a challenge to their own authority and pedagogical methods.

The disagreements escalated into a bitter dispute. Bosse accused his colleagues of misunderstanding or misrepresenting Desargues's principles, while they, in turn, found Bosse to be inflexible and disruptive. The conflict was not merely personal; it reflected deeper debates about the nature of art, the role of rules versus genius, and the best methods for artistic instruction. Figures like the painter Philippe de Champaigne, also a founding member, were involved in these academic debates, which often pitted different theoretical standpoints against each other.

The situation came to a head in 1661 when Abraham Bosse was expelled from the Royal Academy. The official reasons cited were his insubordination and his refusal to conform to the Academy's pedagogical directives. This expulsion was a significant blow to Bosse, but he remained defiant. He continued to teach privately and publish his treatises, establishing his own independent school of art instruction based on his principles. His 1665 Traité des pratiques géométrales et perspectives was published after his expulsion and can be seen as a defense of his methods and a challenge to the Academy's stance.

Technical Innovations and Their Lasting Legacy in Printmaking

Abraham Bosse's contributions to the art of printmaking extended beyond his prolific output; he was also a significant technical innovator and codifier. His 1645 Traicté des manières de graver was a landmark publication, being one of the first, if not the very first, detailed and systematic manuals on the techniques of etching and engraving.

Before Bosse's treatise, knowledge of these intricate processes was often passed down through workshop traditions or learned through trial and error. Bosse meticulously documented the entire printmaking process, from the preparation of the copper plate, the types of grounds (hard and soft varnishes), the use of etching needles and burins, the application of acid (eaux fortes), to the methods of inking and printing. This demystification of the craft was invaluable for aspiring printmakers and helped to standardize and disseminate best practices.

His own etching technique was characterized by remarkable clarity and control. He often employed a system of swelling and tapering lines, more commonly associated with burin engraving, within his etchings. This, combined with carefully managed cross-hatching, allowed him to achieve a wide range of tonal values and a high degree of precision. This meticulousness gave his prints a polished, almost engraved look, which was admired for its refinement. While artists like Rembrandt van Rijn were exploring the more expressive and painterly possibilities of etching with freer lines and rich burr, Bosse championed a more controlled and linear aesthetic.

Bosse was also an early advocate for the use of the échoppe, a type of etching needle with an oval, slanted tip, which allowed for the creation of lines that swelled and tapered, mimicking the effect of a burin. This tool, popularized by Jacques Callot, was instrumental in achieving the calligraphic elegance seen in much of Bosse's work.

The influence of his technical manual was profound and long-lasting. It was translated into German, Dutch, and English, spreading knowledge of these techniques across Europe. Even as new methods and aesthetic approaches emerged, Bosse's treatise remained a foundational text. The later revision by Charles-Nicolas Cochin in the 18th century, titled De la manière de graver à l'eau-forte et au burin, et de la gravure en manière noire (1745), updated and expanded upon Bosse's work, attesting to its enduring importance while also incorporating newer developments like mezzotint.

Through his writings and his own exemplary practice, Bosse helped to elevate the technical standards of printmaking and provided a clear pedagogical framework for its instruction. His emphasis on rational method and precise execution left an indelible mark on the history of the medium.

Social Commentary, Moral Instruction, and Huguenot Identity

Abraham Bosse's prints are more than just aesthetically pleasing images or records of contemporary fashion; they are imbued with social commentary and often carry strong moral messages. His perspective as a Huguenot in a predominantly Catholic society likely sharpened his observational skills and perhaps inclined him towards themes of virtue, diligence, and the transience of worldly pleasures.

Many of his genre scenes, while appearing to be straightforward depictions of daily life, can be interpreted as subtle commentaries on social mores. For instance, his depictions of lavish interiors and elegant gatherings might celebrate refinement, but they can also hint at vanity or superficiality. Conversely, his scenes of artisans at work, such as Le Cordonnier (The Shoemaker) or L'Imprimeur en Taille-Douce (The Intaglio Printer), often convey a sense of dignity in labor and the value of skilled craftsmanship.

His allegorical works are more explicit in their moral instruction. Series like Les Vierges sages et les vierges folles (The Wise and Foolish Virgins) directly illustrate biblical parables with clear lessons about spiritual preparedness and folly. The contemporary settings and attire in these religious prints made the moral lessons more immediate and relevant to his audience. This didactic impulse is a recurring feature in his oeuvre.

The influence of his Huguenot faith can be discerned in the emphasis on sobriety, industry, and domestic virtue that often pervades his work. While he depicted the splendors of courtly life, there is often an underlying sense of order and propriety. His prints rarely venture into the overtly sensual or bacchanalian themes explored by some of his contemporaries, such as certain Flemish artists like Jacob Jordaens or even some aspects of Peter Paul Rubens's work.

His series Les Quatre Saisons (The Four Seasons) or Les Âges de l'Homme (The Ages of Man) use traditional allegorical frameworks to reflect on the passage of time and the human condition, often with an undercurrent of memento mori – a reminder of mortality.

Even his scientific illustrations or depictions of learned professions, like L'Avocat (The Lawyer) or Le Médecin (The Doctor), contribute to a broader picture of an ordered, rational society where knowledge and skill are valued. His commitment to Desarguesian perspective itself can be seen as part of this worldview, an attempt to bring order and rationality to the representation of the world.

Bosse's prints, therefore, function on multiple levels: as historical documents, as works of art, and as vehicles for social and moral commentary, subtly reflecting the values and anxieties of his time, and perhaps, the particular perspective of his religious minority status.

Collaborations, Contemporaries, and Artistic Milieu

Abraham Bosse operated within a rich and dynamic artistic milieu in 17th-century Paris. His career intersected with numerous other artists, printmakers, publishers, and intellectuals, creating a complex web of influences, collaborations, and rivalries.

As mentioned, the publisher Melchior Tavernier was crucial in the early dissemination of Bosse's work. Print publishers like Tavernier, Pierre Mariette I, and later Pierre Mariette II, played a vital role in the art market, commissioning works, distributing prints, and fostering the careers of engravers.

Jacques Callot was a significant early influence, though their direct interaction was limited to Callot's time in Paris. Callot's innovative etching techniques and his thematic focus on contemporary life, including his famous series Les Grandes Misères de la guerre (The Great Miseries of War), set a precedent for detailed, narrative printmaking that Bosse adapted to his own style and subjects. Another contemporary etcher who shared some thematic interests with Callot and Bosse was the Italian Stefano della Bella, who also spent a significant period working in Paris and was known for his delicate and lively prints.

Within the Royal Academy, Bosse's path crossed with many of the leading French artists of the day. Charles Le Brun was his primary antagonist, but other prominent figures included Philippe de Champaigne, a painter of great moral and religious seriousness; Laurent de La Hyre, known for his elegant classicism; and Sébastien Bourdon, a versatile artist who worked in various genres. The debates within the Academy were part of a broader intellectual ferment in France, which also saw the rise of figures like Nicolas Poussin and Claude Lorrain, though they were primarily based in Rome, their classicizing influence was strongly felt in Paris. Poussin, in particular, represented an ideal of rationally ordered, morally serious art that resonated with some of the Academy's goals, albeit expressed through painting rather than primarily through printmaking.

Among fellow printmakers, Bosse was a leading figure. Other notable French engravers of the period included Jean Morin, known for his portraits after Philippe de Champaigne, often using a distinctive combination of etching and stipple; and Robert Nanteuil, who became one of the foremost portrait engravers of the era, working primarily with the burin to achieve remarkable subtlety and psychological depth. While Bosse's style was more linear and descriptive, Nanteuil's work represented the pinnacle of refined portrait engraving.

The intellectual environment also included figures like Girard Desargues, whose mathematical theories Bosse championed. This connection placed Bosse at the intersection of art and science, a position that was not uncommon in the Renaissance but was perhaps less typical for a practicing artist in the 17th century. His efforts to popularize Desargues can be compared to earlier figures like Albrecht Dürer, who also wrote treatises on geometry and perspective for artists.

Bosse's work, with its detailed depiction of French society, also provides a visual counterpoint to the literary descriptions of contemporary life found in the works of writers like Molière or Jean de La Fontaine, who, in their respective fields, also captured the manners and morals of the age.

Later Years and Enduring Influence

After his expulsion from the Royal Academy in 1661, Abraham Bosse did not fade into obscurity. He continued to work, teach, and publish independently. He established his own private school where he taught his principles of perspective and printmaking, attracting students who were perhaps disillusioned with the Academy or sought his specialized knowledge.

His Traité des pratiques géométrales et perspectives, published in 1665, can be seen as a definitive statement of his pedagogical system and a vindication of his stance against the Academy. He remained a staunch defender of Desarguesian perspective throughout his life.

Bosse continued to produce prints, though perhaps not with the same prolific intensity as in his earlier years. His focus remained on subjects that allowed for meticulous detail and often carried moral or instructive undertones. He passed away in Paris on February 14 or 16, 1676.

The enduring influence of Abraham Bosse is multifaceted. Firstly, his vast corpus of prints remains an invaluable historical archive, offering unparalleled visual documentation of 17th-century French society, from its grand ceremonies to its everyday domestic life and trades. Historians of fashion, material culture, and social customs continue to draw upon his work.

Secondly, his technical contributions to printmaking, particularly through his Traicté des manières de graver, had a lasting impact. His manual provided a clear and systematic guide to etching and engraving techniques that benefited generations of artists across Europe. It helped to standardize practices and disseminate knowledge, contributing to the overall development of the printmaking arts.

Thirdly, his advocacy for a rational, geometric approach to perspective, while controversial in his time, contributed to the ongoing dialogue about the relationship between art and science. His efforts to make Desargues's complex theories accessible to artists were significant, even if the Academy ultimately favored a more eclectic approach. His work underscores the importance of perspective as a fundamental tool for artists seeking to create convincing representations of three-dimensional space.

While figures like Rembrandt explored the more expressive and painterly potentials of etching, and engravers like Nanteuil achieved unparalleled subtlety in portraiture, Bosse carved out a unique niche. His strength lay in his clarity, his meticulous detail, and his ability to chronicle his world with precision and insight. His prints may lack the dramatic chiaroscuro of Rembrandt or the profound psychological depth of some portraitists, but they possess a distinct charm, an intellectual rigor, and an informative quality that secure his place in the history of art.

Conclusion: A Legacy of Precision and Principle

Abraham Bosse was a complex figure: a highly skilled craftsman, an ardent theorist, a dedicated teacher, and a keen observer of his society. His unwavering commitment to his principles, particularly his advocacy for Desarguesian perspective, led to conflict but also defined his unique contribution to French art. As an engraver, he left behind a rich visual legacy that continues to inform and delight, offering a detailed and multifaceted portrait of 17th-century France. As a theorist, his writings on perspective and printmaking techniques were foundational, influencing artistic practice and education for many years.

Though sometimes overshadowed by painters who dominated the grand narratives of art history, Abraham Bosse's meticulous etchings and influential treatises ensure his enduring significance. He remains a key figure for understanding the artistic, intellectual, and social currents of the French Baroque, a master whose work exemplifies the power of print to document, instruct, and reflect the world with precision and insight.