The period known as the Northern Renaissance witnessed an explosion of artistic creativity across Germany and the Low Countries, paralleling the innovations occurring in Italy but developing its own distinct character. Central to this era were two towering figures: Albrecht Dürer of Nuremberg and Lucas van Leyden of Leiden. While sometimes mistakenly conflated or linked under erroneous names like "Albert Durer Lucas," they were distinct individuals whose paths crossed significantly, each leaving an indelible mark on the history of art, particularly in the realm of printmaking. This exploration delves into the lives, works, and legacies of these two masters, clarifying their individual identities while acknowledging their important historical connection.

Albrecht Dürer: The German Master

Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528) stands as the preeminent figure of the German Renaissance. Born in the thriving imperial city of Nuremberg, a hub of commerce, humanism, and craft, Dürer was exposed to a rich cultural environment from a young age. His father was a successful goldsmith, and Albrecht initially trained in his workshop, acquiring a fundamental understanding of metalworking and precision that would profoundly inform his later engraving work.

Recognizing his son's exceptional talent for drawing, Dürer's father apprenticed him to the leading Nuremberg painter and woodcut designer, Michael Wolgemut, in 1486. Wolgemut's workshop was a major producer of illustrated books, including the famous Nuremberg Chronicle. Here, Dürer honed his skills in painting and, crucially, learned the techniques of woodcut design, a medium he would revolutionize.

Following his apprenticeship, Dürer embarked on his Wanderjahre, or journeyman years (1490-1494), a traditional period of travel for craftsmen. This journey took him through parts of Germany and likely to Colmar, where he hoped to meet the renowned engraver Martin Schongauer, though Schongauer had died shortly before his arrival. He did, however, connect with Schongauer's brothers, also artists and goldsmiths, and undoubtedly studied Schongauer's sophisticated engraving techniques.

Upon returning to Nuremberg in 1494, Dürer married Agnes Frey and established his own workshop. Almost immediately, he undertook his first transformative journey to Italy, primarily visiting Venice (1494-1495). This trip was pivotal. He encountered firsthand the works of Italian Renaissance masters like Andrea Mantegna and Giovanni Bellini, absorbing their approaches to classical form, human anatomy, perspective, and colour. This Italian influence, synthesized with his Northern European training in detailed realism, became a hallmark of his unique style.

Dürer quickly established an international reputation, largely through his unprecedented mastery of printmaking – both woodcut and engraving. He elevated these mediums from mere illustration to independent art forms. His technical virtuosity was astounding; in engraving, he achieved remarkable tonal variations and textures through intricate networks of lines (burin work), while his woodcuts displayed a complexity and dynamism previously unseen.

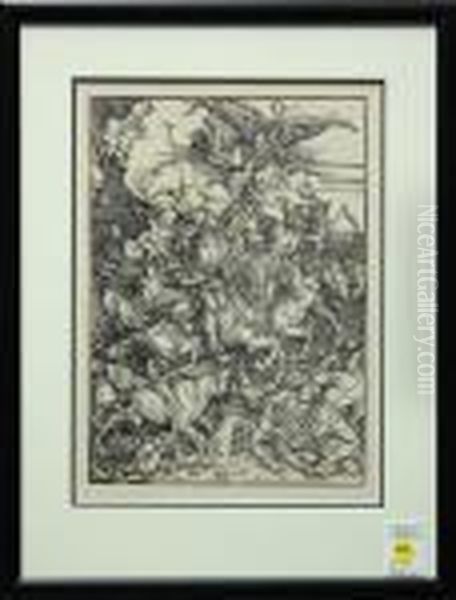

One of his earliest major triumphs was the Apocalypse series of woodcuts (c. 1498). These fifteen large-scale prints, illustrating scenes from the Book of Revelation, were powerful, dramatic, and technically brilliant. Works like The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse showcased his ability to convey complex narratives and intense emotion through the bold contrasts and energetic lines of the woodcut medium. They were widely disseminated and cemented his fame across Europe.

Dürer was also a supremely gifted painter. His Self-Portrait of 1500 (Alte Pinakothek, Munich), presenting himself in a frontal, Christ-like pose, is a profound statement on the elevated status of the artist, reflecting Renaissance humanism. He produced numerous altarpieces, such as the Adoration of the Magi (1504, Uffizi) and the Paumgartner Altarpiece (c. 1500, Alte Pinakothek), demonstrating his skill in composition, colour, and integrating Italianate monumentality with Northern detail.

His second journey to Venice (1505-1507) further deepened his engagement with Italian art theory and practice. He associated with prominent artists like Giovanni Bellini, whom he greatly admired. During this period, he painted the Feast of the Rose Garlands (1506, National Gallery Prague) for the German merchant community in Venice, a work demonstrating his ability to handle large, complex figure compositions with vibrant colour, rivaling his Italian contemporaries.

Returning to Nuremberg, Dürer entered a period of intense productivity, creating some of his most iconic works. His three "Master Engravings" (Meisterstiche) of 1513-1514 – Knight, Death and the Devil, Saint Jerome in His Study, and Melencolia I – represent the pinnacle of his engraving technique and intellectual depth. These works are rich in complex symbolism, exploring themes of faith, mortality, and the nature of creativity, subjects central to the humanist thought of the time.

Dürer's fascination with the natural world is evident in his extraordinarily detailed watercolors and drawings, such as Young Hare (1502) and Great Piece of Turf (1503), both housed in the Albertina, Vienna. These studies reveal his meticulous observation and ability to render texture and life with astonishing precision, elevating nature study to a high art. They demonstrate a scientific curiosity alongside artistic skill.

Beyond his artistic output, Dürer was a significant theorist. He sought to understand and codify the principles of art, particularly perspective and human proportion, partly inspired by his Italian experiences. His major theoretical works, Four Books on Measurement (Underweysung der Messung, 1525) and Four Books on Human Proportion (Vier Bücher von Menschlicher Proportion, published posthumously in 1528), were groundbreaking. They provided practical instruction for artists and craftsmen, disseminating Renaissance principles in Northern Europe and influencing generations of artists.

Dürer's influence was immense and immediate. His prints circulated widely, impacting artists across Germany, the Low Countries, Italy, and beyond. Figures like Raphael and Pontormo in Italy were known to have studied his prints. In Germany, his workshop and style influenced artists like Hans Baldung Grien, Hans von Kulmbach, and the Beham brothers. His elevation of printmaking and his intellectual approach to art fundamentally changed the perception of the artist in Northern Europe.

Lucas van Leyden: The Dutch Prodigy

Lucas Hugensz., known as Lucas van Leyden (c. 1494-1533), was the leading figure of Dutch art in the early 16th century. Born and primarily active in Leiden, he emerged as an artistic prodigy, achieving remarkable mastery, particularly in engraving, at an exceptionally young age. While details of his early life are less documented than Dürer's, tradition holds he may have studied painting with his father, Huygh Jacobsz., and later with Cornelis Engebrechtsz., a prominent Leiden painter.

Regardless of his formal training, Lucas quickly developed a highly original and sophisticated style in engraving. His earliest dated prints, such as Mohammed and the Murdered Monk Sergius (1508), were created when he was merely fourteen, yet they already display astonishing technical skill and narrative complexity. His use of fine, delicate lines and subtle atmospheric perspective set his work apart.

Lucas became renowned for his engravings, which often depicted biblical and historical scenes, as well as pioneering explorations of genre subjects – scenes of everyday life. Works like The Milkmaid (1510) are early examples of peasant life treated as a primary subject, anticipating a major theme in later Dutch art. He rendered these scenes with keen observation and often a touch of anecdotal humour or moral commentary.

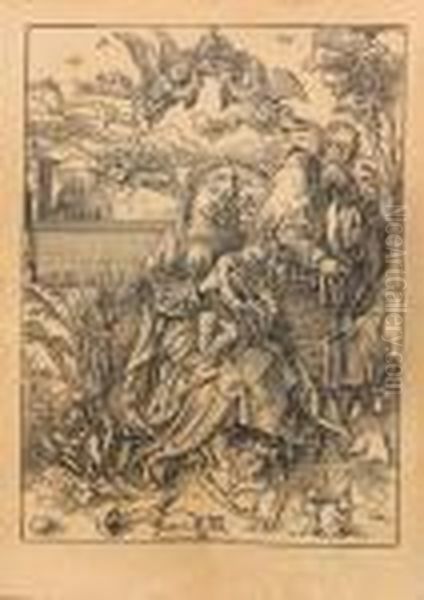

His engravings are characterized by their intricate detail, nuanced depiction of light and atmosphere, and complex, often multi-layered compositions. He excelled at portraying a wide range of human emotions and interactions within crowded scenes. The large engraving Ecce Homo (1510) is a masterful example, presenting the biblical narrative within a vast, detailed cityscape populated by numerous figures, drawing the viewer into the unfolding drama.

While primarily celebrated for his prints, Lucas was also a significant painter, although fewer of his paintings survive. His most famous painted work is the Last Judgment triptych (c. 1526-1527, Stedelijk Museum De Lakenhal, Leiden). This large altarpiece demonstrates his skill in handling complex compositions, dynamic figures, and expressive colour, blending Northern traditions with influences likely absorbed from contemporary artists like Jan Gossaert (Mabuse) and perhaps indirectly from Italian art seen through prints.

Lucas's style evolved throughout his career. His earlier prints often feature delicate lines and silvery tones. Later works sometimes show broader handling and stronger contrasts, possibly reflecting the influence of contemporaries or a conscious stylistic shift. He experimented with different printmaking techniques, including etching and woodcut, though engraving remained his primary medium.

His subject matter was diverse, ranging from traditional religious narratives like Lot and His Daughters (c. 1530, painting, Louvre) to allegorical scenes and portraits. He possessed a remarkable ability to infuse his subjects with psychological depth and narrative interest. His figures, often slender and elegant, interact in ways that suggest complex relationships and underlying stories.

Lucas van Leyden's reputation quickly spread beyond Leiden. His prints were highly sought after by collectors and artists alike. His innovative approach to genre subjects and his technical finesse in engraving had a lasting impact on the development of Dutch art, paving the way for later masters like Pieter Bruegel the Elder (in terms of genre) and Rembrandt (in terms of printmaking). He was a key figure in establishing a distinct Netherlandish artistic identity during the Renaissance.

A Meeting of Masters: Dürer and Lucas in Antwerp

The careers of Albrecht Dürer and Lucas van Leyden intersected directly during Dürer's journey to the Netherlands in 1520-1521. This trip, undertaken partly to secure the confirmation of a pension from the new Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, brought Dürer into contact with numerous artists and intellectuals in the vibrant cities of Antwerp and Brussels. The highlight for art history was his meeting with Lucas van Leyden in Antwerp in June 1521.

Dürer meticulously documented this journey in a detailed diary, which provides invaluable insights into the art world of the time. Regarding Lucas, Dürer recorded their meeting with evident respect. He noted that Lucas, though still young (around 27), was a master engraver. Dürer famously drew a portrait of Lucas using silverpoint, a delicate drawing technique. This sensitive portrait survives today (Musée Wicar, Lille) and captures the intense gaze of the young Dutch artist.

The meeting was clearly one of mutual admiration. Dürer's diary records an exchange of prints between them. Dürer gave Lucas a full set of his engravings, while Lucas presented Dürer with a selection of his own works. This exchange signifies the high esteem in which they held each other's artistry. For Dürer, encountering Lucas's work firsthand confirmed the high level of printmaking skill present in the Low Countries.

While Lucas was already an established master, the encounter with the older, internationally renowned Dürer undoubtedly left an impression. Some art historians detect subtle shifts in Lucas's later work, possibly reflecting Dürer's influence, perhaps in a slightly more robust line or compositional structure in certain prints. However, Lucas largely maintained his distinct, delicate style, characterized by atmospheric depth and nuanced human observation.

Conversely, Dürer's exposure to Netherlandish artists during this trip, including Lucas, Quentin Matsys, and Joachim Patinir, broadened his artistic horizons. He admired their skill in oil painting and landscape, elements that subtly informed his own later works. The meeting in Antwerp underscores the interconnectedness of the Northern European art scene and the respect shared between its leading practitioners.

Enduring Legacies in Art History

Albrecht Dürer's legacy is monumental. He revolutionized printmaking, transforming it into a major art form capable of great expressive power and intellectual depth. His technical innovations and the wide circulation of his prints disseminated his style and Renaissance ideals throughout Europe. His theoretical writings on measurement and proportion provided a crucial bridge between Italian Renaissance theory and Northern European artistic practice. Furthermore, his intense self-portraits advanced the genre and asserted the intellectual and social status of the artist. He remains a cornerstone of German art and a pivotal figure in the broader European Renaissance. His influence touched countless artists, from his German contemporaries like Albrecht Altdorfer and Lucas Cranach the Elder to Italian masters and later printmakers like Rembrandt.

Lucas van Leyden's legacy, while perhaps less globally dominant than Dürer's, is fundamental to the history of Dutch and Netherlandish art. As a printmaker, his technical brilliance and innovative subject matter, particularly his early and sensitive exploration of genre scenes, were highly influential. He demonstrated that engraving could convey subtle atmosphere, psychological nuance, and complex narratives with extraordinary finesse. His work paved the way for the great flourishing of Dutch art in the 17th century, influencing artists who specialized in genre painting and printmaking. Figures like Hendrick Goltzius and later Rembrandt looked back to Lucas as a foundational master of Dutch printmaking.

Together, Dürer and Lucas represent the pinnacle of Northern Renaissance printmaking. Dürer brought unparalleled technical power, intellectual rigor, and a synthesis of Northern detail and Italian form. Lucas offered exquisite refinement, atmospheric subtlety, and pioneering explorations of everyday life. Their brief meeting in Antwerp symbolizes a moment of connection between two of the era's greatest talents, artists who, through their distinct geniuses, profoundly shaped the course of Western art. They were not one artist, "Albert Durer Lucas," but two distinct giants whose work continues to fascinate and inspire.