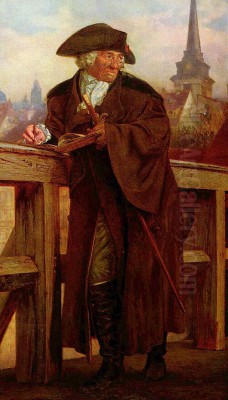

Daniel Nikolaus Chodowiecki stands as a pivotal figure in 18th-century German art, a master printmaker and illustrator whose work provides an unparalleled window into the life, sensibilities, and intellectual currents of the Enlightenment era, particularly within Prussia. Born on October 16, 1726, in the city of Danzig (modern-day Gdańsk, Poland), then part of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth under significant Prussian influence, and passing away in Berlin on February 7, 1801, Chodowiecki's life spanned a period of profound social, political, and cultural transformation. He became renowned primarily for his prolific output of etchings, capturing the nuances of bourgeois existence with remarkable detail, empathy, and often a subtle touch of satire. His legacy is that of an artist deeply engaged with his time, translating the spirit of the Aufklärung into visual form.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in Danzig and Berlin

Chodowiecki's origins were rooted in a merchant family in the bustling port city of Danzig. His father, Gottfried Chodowiecki, was a grain merchant, providing a connection to the commercial life of the city. His mother, Marie Henriette Ayrer, was of Huguenot descent, tracing her lineage back to French Protestants who had sought refuge abroad. This mixed heritage – Polish, German, and French Huguenot – would subtly inform his perspective throughout his life. His early education likely included the basics necessary for a commercial career, following in his father's footsteps.

The trajectory of his life shifted significantly following his father's death in 1740. Around 1743, Daniel and his younger brother Gottfried were sent to Berlin to live with their maternal uncle, Antoine Ayrer, who owned a business. Initially, Daniel was expected to pursue a commercial path. However, Ayrer, who practiced enamel painting on small items like snuffboxes as a pastime, introduced the young Chodowiecki brothers to the rudiments of art. This exposure ignited a passion in Daniel that would ultimately define his life.

While working in commerce, Chodowiecki diligently pursued artistic self-education during his free time. He studied drawing, learned miniature painting, and crucially, taught himself the intricate techniques of etching. This period of autodidactic learning was foundational, instilling in him a discipline and meticulousness that would characterize his later work. He gradually gained proficiency, initially creating small-scale works, often miniatures and enamel paintings, reflecting his uncle's influence but increasingly showing his own developing style.

The Turn to Professional Artistry

By the mid-1750s, Chodowiecki's dedication to art had grown to the point where he decided to abandon his commercial pursuits entirely and devote himself to becoming a professional artist. This was a significant decision, moving away from the relative security of trade into the less certain world of art patronage and commissions. His marriage in 1755 to Jeanne Barez, the daughter of a Huguenot silk embroiderer in Berlin, further solidified his ties within the city's Huguenot community and provided a stable domestic foundation.

His early professional years focused on painting, including miniatures and some oil paintings. However, it was in the medium of printmaking, particularly etching, that Chodowiecki found his true calling and achieved widespread recognition. Etching allowed for the relatively inexpensive reproduction and dissemination of images, making it an ideal medium for reaching the growing middle-class audience interested in literature, social commentary, and scenes of everyday life – subjects that resonated deeply with Chodowiecki's own inclinations.

He rapidly developed a distinctive etching style characterized by fine lines, delicate hatching, and a remarkable ability to capture character, gesture, and atmosphere within often small formats. His technical skill was exceptional, allowing him to render textures, light, and complex compositions with apparent ease. This technical mastery, combined with his keen observational skills, set the stage for his emergence as one of the leading graphic artists of his generation in Germany.

Illustrator of the Enlightenment

Chodowiecki's reputation soared through his work as an illustrator for the burgeoning book market of the Enlightenment. The era saw an explosion in publishing, with novels, philosophical treatises, educational texts, and almanacs reaching an ever-wider readership. Illustrations were highly valued, serving not only to embellish texts but also to interpret and visualize their content, making complex ideas or narratives more accessible. Chodowiecki proved exceptionally adept at this task.

He created thousands of illustrations for a vast array of publications. Among his most celebrated works were illustrations for Johann Bernhard Basedow's influential educational work, Elementarwerk (1774), which aimed to reform teaching methods through visual aids. His images brought Basedow's pedagogical concepts to life, depicting scenes of learning, nature, and trades with clarity and charm. He also provided illustrations for Johann Kaspar Lavater's Physiognomische Fragmente (Essays on Physiognomy, 1775–78), a highly popular, though controversial, work that attempted to discern character from facial features. Chodowiecki's precise renderings of human heads and expressions were crucial to Lavater's project.

His illustrations graced editions of major literary works, both German and international. He created plates for German authors like Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (including early editions of The Sorrows of Young Werther), and Friedrich Schiller. He also illustrated translations of foreign classics, such as Miguel de Cervantes' Don Quixote, Laurence Sterne's A Sentimental Journey, and Oliver Goldsmith's The Vicar of Wakefield. His small, detailed etchings for these works were highly sought after, often appearing in popular pocket almanacs and calendars, which further broadened his reach.

Masterworks and Signature Style

Beyond book illustration, Chodowiecki produced numerous independent prints and series that cemented his fame. One of his most famous early works is the etching Calas Bidding Farewell to his Family (1767). This print depicted a scene related to the tragic case of Jean Calas, a Huguenot merchant in Toulouse unjustly accused and executed for murdering his son. The case became a cause célèbre championed by Voltaire, symbolizing religious intolerance and judicial error. Chodowiecki's sensitive portrayal captured the emotional intensity and pathos of the moment, aligning with the Enlightenment's emphasis on reason, justice, and human feeling (Empfindsamkeit or Sensibility).

His series Natural and Affected Actions of Life (Natur und affectirte Handlungen des Lebens) explored human behavior and social manners, contrasting genuine emotion with artificial posturing, often with a gentle satirical edge. This reflected the era's interest in authenticity and the critique of aristocratic affectation, themes also explored by contemporaries like the English painter and printmaker William Hogarth, to whom Chodowiecki was often compared, earning him the moniker "the German Hogarth." While Hogarth's satire was often biting and overtly moralizing, Chodowiecki's tended to be more subtle and observational.

A particularly personal and revealing work is the series of illustrations documenting his Journey from Berlin to Danzig (Die Reise von Berlin nach Danzig) undertaken on horseback in 1773 to visit his aging mother. He kept a detailed diary and sketchbook, recording the people, places, and incidents encountered along the way. The resulting prints offer a fascinating glimpse into the landscapes, customs, and social strata of provincial Prussia and Poland. They showcase his talent for capturing fleeting moments and character types with immediacy and charm.

Chodowiecki's style skillfully navigated the transition from the waning Rococo to the emerging Neoclassicism. His work often retained a Rococo lightness and elegance, particularly in decorative elements and the depiction of fashionable society. However, his commitment to realism, his focus on bourgeois life, and the clarity and emotional directness of his narratives aligned him more closely with Enlightenment ideals and the burgeoning Neoclassical aesthetic. He avoided the grandiosity of much historical painting, preferring intimate, relatable scenes rendered with precision and psychological insight. His work shares some affinities with French genre painters like Jean-Baptiste Greuze, who also focused on sentimental and moralizing domestic scenes, though Chodowiecki's scope was broader and his medium primarily graphic.

Chodowiecki and the Berlin Academy of Arts

Chodowiecki's rising stature was formally recognized through his involvement with the Prussian Academy of Arts (Königlich Preußische Akademie der Künste) in Berlin. Founded under Frederick I, the Academy was a central institution for artistic training and discourse in Prussia. Chodowiecki became a member in 1764. His influence within the institution grew steadily over the years.

He was appointed Rector of the Academy in 1783, a position that involved significant administrative and educational responsibilities. He played a role in shaping the curriculum and guiding students. His practical experience and his reputation as a master draftsman and etcher made him a respected figure. Later, from 1797 until his death in 1801, he served as the Academy's Director, its highest office. This appointment underscored his preeminence in the Berlin art world at the close of the 18th century.

His tenure at the Academy placed him at the heart of artistic life in the Prussian capital. While direct records of extensive collaboration with specific painter contemporaries like the portraitist Anton Graff or the internationally renowned Angelica Kauffman (who worked across Europe but was admired in Germany) are scarce, his position ensured he was aware of, and interacted with, the leading artistic figures of the day. He would have been familiar with the work of court painters who preceded him, such as Antoine Pesne, and later contemporaries like the sculptor Johann Gottfried Schadow, who eventually succeeded him as Director of the Academy. His influence extended through the students he taught and the standards he upheld.

A European Context: Influences and Contemporaries

While firmly rooted in the Berlin art scene, Chodowiecki's work existed within a broader European context. His meticulous technique and focus on everyday life show an awareness of the legacy of 17th-century Dutch Golden Age masters, particularly in genre scenes and etching techniques, potentially echoing the spirit, if not the direct style, of artists like Rembrandt van Rijn in the handling of light and character in prints.

The elegance found in some of his work suggests an absorption of French Rococo aesthetics, perhaps filtered through the engravings of artists associated with Antoine Watteau or François Boucher, though Chodowiecki adapted these influences to his own, more sober, bourgeois subjects. His engagement with Enlightenment themes naturally connected him intellectually with figures across Europe. His illustrations for Voltaire and Rousseau placed him directly in dialogue with the French Enlightenment.

Comparisons with William Hogarth in England are frequent and apt, given both artists' focus on contemporary life, social commentary, and the use of print series to tell stories. However, their tones differed, with Hogarth often employing harsher satire and grander narrative cycles. Jean-Baptiste Greuze in France shared Chodowiecki's interest in sentimental domestic scenes, reflecting the widespread European movement of Sensibility.

Other notable contemporaries in the graphic arts included the German etcher Johann Georg Wille, who achieved great success in Paris and influenced printmaking across Europe. In Italy, Giovanni Battista Piranesi was creating dramatic etchings of Roman antiquities, vastly different in subject and scale but demonstrating the power of the etched line during the same period. Later in Chodowiecki's life, the powerful and often dark etchings of the Spanish master Francisco Goya began to emerge, offering a stark contrast in temperament and vision. Chodowiecki's unique contribution lies in his specific focus on the German middle class and his prolific output as an illustrator, capturing the particular zeitgeist of the Prussian Enlightenment.

Chronicler of His Time

More than just an artist, Chodowiecki acted as a visual historian of his era. His vast body of work forms an invaluable record of 18th-century German society, particularly the life of the bourgeoisie in Berlin. He depicted their homes, clothing, manners, occupations, and leisure activities with unparalleled detail and accuracy. From intimate family scenes to public gatherings, his prints document the material culture and social customs of the time.

He did not shy away from depicting historical events. He produced prints relating to the Seven Years' War and, significantly, created numerous images responding to the French Revolution. These prints, often small and intended for almanacs, captured key moments and figures of the Revolution, reflecting the intense interest and mixed reactions these events provoked across Europe. They served as a form of visual news reporting, disseminating images of distant upheavals to a German audience.

His engagement with social themes extended to works like his Dance of Death series. While the Totentanz was a traditional medieval theme, Chodowiecki adapted it, using the allegorical figure of Death interacting with people from various walks of life to offer social commentary, sometimes satirical, sometimes poignant, reflecting on mortality and the vanities of worldly existence. This adaptation showcased his ability to reinterpret traditional motifs through an Enlightenment lens.

Identity and Personal Life

Chodowiecki maintained a connection to his Polish roots throughout his life, despite spending his entire adult career in Berlin. He famously referred to himself in letters, with a touch of humor, as "ein polnischer Nanteuil von Berlin" (a Polish Nanteuil – referencing the great French portrait engraver Robert Nanteuil – from Berlin) and sometimes signed correspondence acknowledging his Danzig origins. His 1773 journey back to Danzig was not just a visit but a reaffirmation of this connection, meticulously documented in his diary and sketches. He depicted Polish historical figures and scenes as well, indicating a lasting interest in the land of his birth.

His Huguenot heritage also played a significant role. The Huguenot community in Berlin was influential, known for its industry, craftsmanship, and distinct cultural identity. Chodowiecki's marriage into this community and his frequent depiction of its members suggest a strong sense of belonging. His own qualities of diligence, precision, and rationality align well with the values often associated with the Huguenot work ethic.

Anecdotes reveal his meticulous nature extended beyond his art. He was known to be highly organized and disciplined. His interest in the technical aspects of his craft was profound; reports suggest he even tested the quality and permanence of different pigments himself, seeking the best materials for his work, whether in etching, enamel, or occasional painting. His life seems to have been one of focused industry and quiet domesticity, centered around his family and his prolific artistic production.

Legacy and Influence

At the time of his death in 1801, Daniel Nikolaus Chodowiecki was one of the most respected artists in Prussia, the esteemed Director of the Berlin Academy. His prints had circulated widely for decades, shaping the visual culture of the German Enlightenment. He had successfully captured the spirit of his age – its intellectual curiosity, its emphasis on sentiment and reason, its growing interest in the lives of ordinary people.

While the grander Neoclassicism of painters like Jacques-Louis David in France or even German contemporaries like Johann Heinrich Wilhelm Tischbein (famous for his portrait of Goethe in the Roman Campagna) might have overshadowed Chodowiecki in terms of monumental painting, his influence in graphic arts and illustration was immense. He set a standard for book illustration that persisted into the 19th century.

Later artists, particularly those interested in realism and historical detail, looked back at his work with admiration. The great 19th-century German realist Adolph Menzel, known for his detailed depictions of the era of Frederick the Great, was a known admirer of Chodowiecki's meticulous observation and historical accuracy. Chodowiecki's prints remain invaluable resources for historians studying 18th-century German culture, fashion, and society.

His reputation as the "German Hogarth" highlights his role as a social commentator, but his work possesses its own distinct character – less biting, perhaps more intimate and empathetic. He provided a visual counterpart to the literature and philosophy of the German Enlightenment, making its ideals and concerns tangible and relatable.

Conclusion: An Enduring Vision

Daniel Nikolaus Chodowiecki's enduring importance lies in his role as the preeminent visual chronicler of the German Enlightenment. Through thousands of etchings, he captured the nuances of middle-class life, illustrated the key texts of the era, and documented the changing social and political landscape with unparalleled skill and sensitivity. His art bridged the elegance of the Rococo with the rational clarity and emotional depth of Neoclassicism and the Empfindsamkeit movement. As a master etcher, influential educator, and Director of the Berlin Academy, he shaped the artistic world of his time. His legacy endures not only in the historical value of his images but also in their artistic merit – the delicate precision of his line, his keen eye for detail, and his profound understanding of the human condition in a transformative age. His work remains a vital testament to the spirit of 18th-century Prussia and the broader European Enlightenment.