Adam Buck stands as a fascinating figure in the art history of the late Georgian and Regency periods. Born in Ireland in 1759 and carving out a successful, albeit fluctuating, career primarily in London until his death in 1833, Buck specialized in portraiture, particularly miniatures and small-scale watercolors. His work is strongly characterized by the Neoclassical style that swept across Europe, yet he adapted it with a unique delicacy and charm that found favour, especially in the burgeoning market for prints and decorative arts. Though his fame waned in the later nineteenth century, recent scholarship and exhibitions have rightfully sought to re-evaluate his contribution, revealing an artist adept at capturing the elegance of his era and navigating the changing tides of taste and commerce. This article delves into the life, work, and context of Adam Buck, exploring his Irish origins, his London success, his artistic innovations, his relationships with contemporaries, and his enduring legacy.

Irish Origins and Early Influences

Adam Buck entered the world in Cork, Ireland, in 1759. His background was rooted in craftsmanship; he hailed from a family of silversmiths, suggesting an early exposure to skilled design and intricate work, which may have informed his later precision in miniature painting and engraving. Information regarding his formative years and artistic training in Ireland remains somewhat scarce, a fact that adds a layer of intrigue to his biography. However, it is known that he was active as an artist in Cork before seeking broader horizons.

The artistic environment in Ireland, particularly Dublin, during the latter half of the 18th century, was experiencing its own wave of Classical Revival. This movement, fueled by interest in archaeological discoveries and classical ideals, undoubtedly shaped Buck's developing aesthetic. The Palladian architecture and Neoclassical interiors popular among the Anglo-Irish ascendancy would have provided a visual backdrop. It is highly probable that Buck absorbed these influences, which emphasized order, harmony, elegant lines, and motifs drawn from antiquity, before he made the pivotal decision to move to London. This grounding in Neoclassicism would become a defining feature of his mature style.

Arrival in London and Establishing a Career

In 1795, Adam Buck relocated from Ireland to London, the vibrant and competitive centre of the British art world. This move marked the beginning of the most significant phase of his career. London offered greater opportunities for patronage, exhibition, and the dissemination of his work through the burgeoning print market. Shortly after his arrival, he established a crucial professional relationship with the publisher and printseller William Holland of Oxford Street. Holland became instrumental in popularizing Buck's designs, commissioning and publishing numerous stipple engravings based on his watercolors.

The London art scene Buck entered was dynamic. Portraiture was in high demand, dominated by celebrated figures like Sir Thomas Lawrence, who was known for his flamboyant brushwork and society portraits, and the Scottish master Sir Henry Raeburn, famed for his robust character studies. Earlier figures like Thomas Gainsborough and George Romney had also left a significant mark on portraiture styles. Buck needed to carve his own niche. Initially, he worked in media like pastel and oil, but these were perhaps falling slightly out of vogue for the type of intimate portraiture he excelled at. He increasingly turned to watercolor, a medium perfectly suited to the delicate linearity and refined finish demanded by the Neoclassical taste he embraced.

The Neoclassical Aesthetic

Adam Buck's art is inextricably linked with the Neoclassical movement. This style, which emerged in the mid-18th century and dominated European art until the early 19th century, championed the perceived virtues of classical antiquity: rationality, clarity, order, and moral seriousness, often reacting against the perceived frivolity of the preceding Rococo style. Thinkers like Johann Joachim Winckelmann promoted the "noble simplicity and calm grandeur" of Greek art, while archaeological excavations at Pompeii and Herculaneum provided direct inspiration. Artists like Jacques-Louis David in France and Antonio Canova in Italy were leading proponents on the continent.

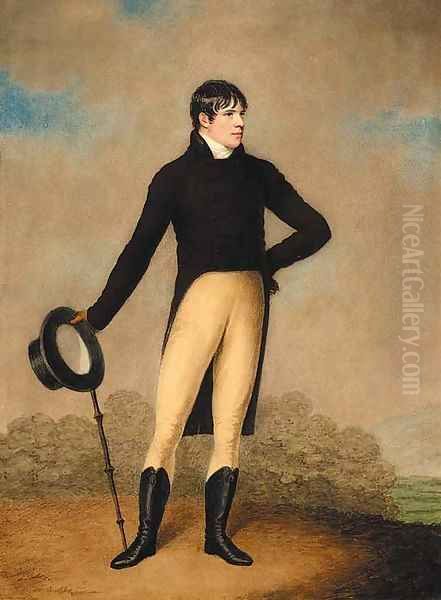

Buck absorbed these principles and translated them into his portraiture and genre scenes. His figures often adopt poses reminiscent of classical sculpture or figures on Greek vases – profiles, elegant contrapposto stances, or graceful three-quarter views replaced the more direct, confrontational poses common earlier. Drapery is often simplified, falling in clean, linear folds that suggest classical attire rather than detailing contemporary fashion with fussy accuracy. Backgrounds are typically plain or minimally suggested, focusing attention entirely on the subject. His color palettes are often restrained, emphasizing drawing and line – what the French called 'dessin' – over painterly effects, or 'couleur'.

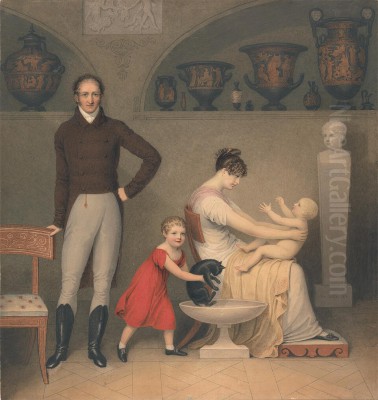

This affinity for Greek forms was not merely stylistic; Buck actively studied ancient sources. He published a significant work titled Paintings on Greek Vases (1811), which contained numerous engravings based on Sir William Hamilton's renowned collection of ancient pottery, now housed in the British Museum. This publication underscored his scholarly interest and provided models for himself and other artists and designers seeking authentic classical motifs. His Portrait of the Edgeworth Family, for instance, clearly demonstrates this understanding, arranging the figures with a compositional harmony and linear grace derived from classical reliefs and vase painting.

Master of Miniatures and Small Portraits

While Buck worked in various formats, he became particularly renowned for his miniatures and small-scale watercolor portraits. Portrait miniatures had been popular since the 16th century, but they enjoyed a particular vogue during the late 18th and early 19th centuries as intimate keepsakes and tokens of affection, worn as jewellery or kept in special cases. This was the era before photography, making these small, detailed likenesses highly valued.

Buck excelled in this demanding genre. Working typically on ivory or paper, he captured likenesses with remarkable delicacy and precision. His miniatures often share the Neoclassical characteristics of his larger works: elegant poses, simplified settings, and an emphasis on graceful contours. He competed in a field populated by other highly skilled miniaturists, such as the fashionable Richard Cosway, known for his flattering, feathery style; George Engleheart, who produced a vast number of high-quality portraits; and the precise John Smart, who also worked in India. Buck's style offered a distinct blend of Neoclassical purity and Regency charm.

His small watercolor portraits on paper served a similar function but allowed for slightly larger compositions, often depicting figures full-length or in small groups. These works, frequently intended as models for engravers, possess a fresh, appealing quality. The use of watercolor allowed for subtle washes of color and crisp linework, perfectly aligning with the Neoclassical aesthetic. These intimate portraits captured the fashions and sensibilities of the Regency elite and aspiring middle classes.

Prints, Porcelain, and Popular Appeal

A crucial factor in Adam Buck's success and influence was the effective dissemination of his work through prints and decorative applications. His partnerships with publishers like William Holland and, later, the enterprising Rudolf Ackermann, were key. Ackermann, operating from his famous Repository of Arts on the Strand, was a major tastemaker, publishing prints, books, fashion plates, and selling a variety of luxury goods.

Buck's charming and elegant designs, particularly those featuring fashionable women, children, and sentimental family groups, proved immensely popular with the public. Stipple engraving, a technique allowing for soft tonal gradations ideal for reproducing watercolor washes and delicate modelling, was often used for prints after Buck's originals. These prints were affordable to a wider audience than commissioned paintings, allowing Buck's Neoclassical style to permeate middle-class homes.

Furthermore, Buck's designs were frequently adapted for decorating porcelain, particularly items produced by the burgeoning Staffordshire potteries and other manufacturers. Tea sets, plates, jugs, and decorative plaques adorned with Buck-inspired figures became fashionable items. Ackermann himself sold ceramics decorated with patterns derived from Buck's watercolors. This translation of his art onto everyday objects significantly broadened his reach and embedded his aesthetic into the visual culture of the Regency period. He became, in effect, a brand name associated with elegance and classical taste.

Subject Matter: Family, Children, and Society

Adam Buck's subject matter often revolved around themes resonant with the sensibilities of the Regency era. Portraits of individuals and families formed the core of his output, commissioned by a clientele seeking refined likenesses. He was particularly adept at portraying women and children, often depicted with an idealized grace and innocence that appealed to contemporary notions of domesticity and sentiment.

His depictions of mothers and children are numerous and characteristic. Often titled generically, such as Mamma at Romps or Mother's Pet, these scenes emphasize tender interactions and familial bonds, rendered with his signature Neoclassical elegance. Children are shown playing, learning, or interacting affectionately with parents, reflecting the growing Enlightenment-era interest in childhood and education, themes also explored by contemporaries like the Swiss-born artist Angelica Kauffman, who enjoyed immense popularity in London.

Buck also painted figures from fashionable society and the literary world. His portrait of the Edgeworth family, including the novelist Maria Edgeworth, is a notable example, capturing the intellectual and familial circle of a prominent Anglo-Irish family. He also depicted actors, society hostesses, and other public figures, reflecting the era's fascination with celebrity and social standing. These works provide valuable visual records of the personalities and social milieu of Regency Britain.

The Mary Anne Clarke Scandal and its Aftermath

Adam Buck's career intersected with a major public scandal in 1809: the investigation into Mary Anne Clarke, the former mistress of Prince Frederick, Duke of York (King George III's second son). Clarke was accused of accepting money in exchange for using her influence with the Duke to secure army commissions and promotions. The parliamentary inquiry and subsequent press coverage caused a sensation.

Buck became involved, not directly in the affair, but as an artist whose images of Mary Anne Clarke became incredibly popular during the scandal. Clarke, a shrewd self-promoter, seems to have understood the power of image. Portraits of her, including those designed by Buck and disseminated widely as prints (often published by William Holland) and on ceramics, circulated extensively. These images, rendered in Buck's typically elegant and classicizing style, arguably helped to shape public perception of Clarke, perhaps softening her image from that of a scandalous courtesan to a figure of public fascination, even a sort of anti-establishment heroine for some.

However, this association may have had repercussions. Sources suggest that Buck had a disagreement with his publisher William Holland around this time, possibly over the nature or perceived impropriety of some of the Clarke-related subjects. Following this period, Buck reportedly focused on more conventionally "decorous" themes. This episode highlights the complex interplay between art, commerce, public scandal, and artistic reputation in the period.

Technique and Versatility

Adam Buck demonstrated considerable versatility across different artistic media. While best known for his watercolors and miniatures, his technical repertoire also included oil painting, pastels, and engraving. His early career likely involved more work in oil and pastel, traditional media for portraiture. However, his shift towards watercolor on paper or ivory proved particularly successful, aligning perfectly with the linear precision and delicate finish favoured in Neoclassical aesthetics and miniature painting.

His skill as a draftsman was fundamental to his success in all media. The clear, confident outlines and graceful contours that define his style are evident whether in a finished watercolor, a miniature, or an engraving. He was also an accomplished engraver himself, producing prints, often using the stipple technique, which allowed for subtle tonal modelling suitable for reproducing the nuances of his drawings and watercolors. His engravings often depicted the sentimental mother-and-child themes for which he was known, showcasing his ability to convey intimacy and emotion through line and tone. This technical facility allowed him to control the reproduction of his designs and cater to different segments of the art market.

Contemporaries and the Artistic Milieu

To fully appreciate Adam Buck's position, it's essential to view him within the rich artistic landscape of his time. In London, he worked alongside and competed with a host of talented artists. In the realm of grand portraiture, Sir Thomas Lawrence was the dominant figure, painter to the King and the aristocracy, known for his dazzling technique. John Hoppner was another major rival in society portraiture.

Within the Neoclassical sphere, Buck's work resonates with that of John Flaxman, primarily a sculptor but hugely influential through his minimalist, linear designs based on Homer and other classical sources, which were widely circulated as engravings. The Swiss-born Angelica Kauffman and the American-born Benjamin West (President of the Royal Academy) were also key figures promoting historical and classical subjects, though in a grander, more painterly style than Buck's typical output.

In the specialized field of miniature painting, as mentioned, Richard Cosway, George Engleheart, John Smart, and Andrew Robertson were prominent contemporaries. The print market involved skilled engravers like Francesco Bartolozzi, who engraved works by many leading artists, and publishers like Holland, Ackermann, and the Boydells, who played a crucial role in disseminating art to a wider public. Buck exhibited his work periodically at the Royal Academy of Arts, placing him within the mainstream exhibition culture of the day, even if his primary income likely derived from private commissions and designs for reproduction.

Later Life and Legacy

Adam Buck continued to work in London throughout the later years of the Regency and into the reign of William IV. While his style remained popular for a considerable period, particularly through prints and decorative arts, the peak of his fame seems to have been in the first two decades of the 19th century. Changing tastes, perhaps moving towards the more Romantic and later Victorian sensibilities, may have gradually lessened the demand for his specific brand of Neoclassical elegance. The advent of photography in the decades following his death would eventually eclipse the traditional role of miniature painting as a means of producing small, portable likenesses.

He died in London in 1833. For much of the later 19th and 20th centuries, his work, like that of many artists perceived as primarily decorative or illustrative, received relatively little critical attention compared to the 'great masters' of oil painting. His name remained known primarily to collectors of miniatures, prints, and ceramics.

Rediscovery and Collections

In recent decades, there has been a renewed scholarly and curatorial interest in Adam Buck. Exhibitions, such as one organized by the Crawford Art Gallery in his native Cork and a notable display at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford in 2015, have sought to reassess his contribution and bring his work to a wider audience. This revival of interest recognizes the quality and charm of his art, his significance within the Neoclassical movement, and his role in the visual culture of the Regency period, particularly in bridging the gap between 'high art' and popular decorative arts through the medium of print.

Today, Adam Buck's works are held in numerous public collections. Significant holdings can be found at the Ashmolean Museum, the National Gallery of Ireland (recognizing his Irish origins), the Victoria and Albert Museum (particularly prints and miniatures), the British Museum (prints and drawings, including works related to his Greek vase studies), and the Royal Collection Trust. His works also appear in other national and international museums. While definitive records are scarce, works undoubtedly remain in private collections, occasionally surfacing on the art market, though perhaps less frequently in major public auctions compared to some of his contemporaries. The collection of the American financier J. Pierpont Morgan, a noted collector of miniatures, included works by Buck, attesting to his appeal among discerning connoisseurs.

Conclusion

Adam Buck emerges from the shadows of art history not as a revolutionary figure, but as a highly skilled and successful artist who perfectly captured the spirit of his age. His Irish roots and London career place him at a nexus of cultural exchange. His embrace of Neoclassicism, filtered through a lens of Regency elegance and charm, resulted in a distinctive and widely appealing style. He excelled in the intimate formats of the miniature and the small-scale watercolor portrait, demonstrating exquisite draftsmanship and a delicate sensibility.

Crucially, Buck understood and utilized the power of reproduction. Through his collaborations with publishers like Holland and Ackermann, his designs reached an unprecedentedly broad audience via prints and decorated ceramics, making him a key figure in popularizing Neoclassical taste. Whether depicting society figures, idealized family groups, or illustrating classical themes, his work consistently reflects clarity, grace, and a refined aesthetic. Though overshadowed for a time, Adam Buck's art offers a valuable window onto the tastes, fashions, and social dynamics of the late Georgian and Regency periods, securing his place as a significant minor master within British and Irish art history.