William Stephen Coleman (1829-1904) stands as a fascinating, albeit sometimes overlooked, figure in the rich tapestry of British Victorian art. A man of diverse talents, he navigated the worlds of illustration, watercolour painting, and ceramic design with considerable skill and success. Though perhaps not as universally recognized today as some of his contemporaries, Coleman's contributions, particularly his delicate watercolours and his pioneering work with Minton's Art Pottery Studio, mark him as an important artist of his time, deeply engaged with the prevailing aesthetic currents of the latter half of the 19th century.

Early Life and Artistic Inclinations

Born in Horsham, Sussex, in 1829, William Stephen Coleman's path to an artistic career was not initially straightforward. His father was a physician, and Coleman himself first pursued medical training, seemingly destined for a career as a surgeon. However, the pull towards the arts proved strong, likely nurtured by his mother's side of the family, which had artistic connections. Discovering and developing his innate talent for drawing and painting, Coleman ultimately abandoned medicine to dedicate himself fully to a life in art.

This early period saw him collaborating with his sister, Rebecca Coleman, who assisted him in preparing woodblocks for engraving. This familial partnership highlights the practical beginnings of his artistic endeavours, grounding his later, more refined work in the craft of printmaking and illustration. This decision to pivot from a stable medical career to the less certain world of professional art speaks to a deep-seated passion and confidence in his creative abilities.

The Illustrator: Capturing Nature's Intricacies

Coleman first gained significant recognition as an illustrator, particularly noted for his work in natural history. His keen eye for detail and delicate rendering made him well-suited to capturing the subtleties of the natural world. He became a prolific book illustrator, contributing significantly to the Victorian public's growing interest in nature and science. His illustrations were not mere scientific records; they possessed an artistic charm and sensitivity that appealed to a broad audience.

Among his notable early successes were his illustrations for W. S. Coleman's own Our Woodlands, Heaths and Hedges, published in 1859, and British Butterflies, published the following year in 1860. These volumes showcased his ability to combine accurate observation with aesthetic appeal. His reputation in this field led to significant collaborations, most notably with the botanist Thomas Moore, for whom he illustrated works such as the popular The Nature-Printed British Ferns.

Coleman also worked alongside other prominent illustrators of the day, including Harrison Weir, known for his animal pictures, and Joseph Wolf, another celebrated natural history artist. These collaborations placed Coleman firmly within the circle of leading Victorian illustrators who were shaping the visual culture of the era through books and periodicals. His work shared the public stage with that of other beloved illustrators like Kate Greenaway and Randolph Caldecott, though Coleman's focus remained more strongly rooted in naturalism.

Mastery in Watercolour

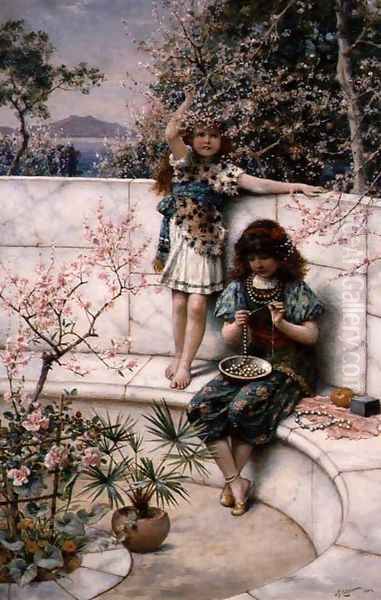

While illustration provided a foundation for his career, Coleman became particularly renowned for his exquisite watercolours. He developed a distinctive style characterized by its refinement, classical undertones, and often idyllic portrayal of figures within landscapes. His technical skill in the medium was considerable, marked by delicate washes, fine detail, and a sensitive handling of light and colour, often creating a soft, almost ethereal atmosphere.

His subject matter frequently involved graceful figures, often women or children, placed within lush, natural settings. Works such as A Naiad or nymph with conch shell point towards a classical or mythological inspiration, aligning him with aspects of the Aesthetic Movement. Other pieces, like Mother and Child Feeding Ducks (recorded as selling for £600, a respectable sum indicating contemporary appreciation) or Lovely Child in a Tree, highlight his ability to capture tender, sentimental moments infused with the beauty of the natural world. Titles like Early Spring Blossom and Love Birds further underscore his affinity for nature and gentle themes. Another mentioned title is Hooked, though specifics about this work are less clear.

Coleman's landscape and figurative watercolours often drew comparisons to the work of Myles Birket Foster, another highly popular Victorian watercolourist known for his detailed and charming rural scenes. Both artists shared a talent for depicting the picturesque qualities of the English countryside and incorporating figures seamlessly into these settings. However, Coleman often introduced a more pronounced classical or aesthetic sensibility into his figure subjects compared to Foster's more purely rustic genre scenes.

Ventures in Ceramic Art: The Minton Connection

Demonstrating his versatility, Coleman extended his artistic endeavours into the realm of decorative arts, specifically ceramics. In the late 1860s and early 1870s, he began designing decorations for the prestigious Minton factory, one of Britain's leading ceramic manufacturers. His designs, often featuring naturalistic motifs like flowers, birds, and insects, aligned perfectly with the growing taste for art pottery influenced by the Aesthetic Movement.

His involvement deepened significantly in 1871 when he took on the role of director for Minton's newly established Art Pottery Studio, located in Kensington Gore, London. This studio was a pioneering venture, aiming to produce high-quality, artist-decorated ceramics distinct from the factory's mass-produced wares. Under Coleman's guidance, a team of artists, many of them women, hand-painted tiles, chargers, vases, and other items, often based on his designs or working within the naturalistic style he championed.

The Minton Art Pottery Studio quickly gained acclaim for its artistic quality and became an important centre for ceramic art in the Aesthetic style, alongside the work of designers like William Morris or Christopher Dresser, though focusing specifically on painted earthenware. Coleman's leadership fostered an environment where decorative art was elevated, blurring the lines between fine art and craft. Tragically, the studio's promising run was cut short when a devastating fire destroyed it in 1875. Despite its brief existence, the studio, under Coleman's direction, made a lasting impact on Victorian ceramic design. An example of work from this period is the Art Pottery Charger dated 1878, likely completed just after the studio's closure or representing the style it fostered.

Artistic Style and Influences

William Stephen Coleman's artistic style can be summarized as a blend of naturalism, classical grace, and Victorian sentiment, executed with technical finesse, particularly in watercolour. His grounding in natural history illustration instilled in him a respect for accurate observation, which remained evident even in his more idealized or decorative works. The influence of Myles Birket Foster is apparent in his landscape settings and his penchant for detailed, picturesque scenes.

However, Coleman's work also aligns significantly with the Aesthetic Movement, which emphasized "art for art's sake," beauty, and decorative quality. His elegant figures, often clad in flowing, vaguely classical drapery, and his focus on harmonious compositions and refined beauty resonate with the work of Aesthetic painters like Albert Joseph Moore or Frederic Leighton. While perhaps less radical than James McNeill Whistler, Coleman shared the movement's interest in visual harmony and decorative effect.

His style offers a contrast to the more narrative-driven and morally charged work of the Pre-Raphaelites, such as John Everett Millais, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, or William Holman Hunt. Coleman's art aimed more at evoking mood, beauty, and gentle sentiment rather than conveying complex stories or overt symbolism. His engagement with both fine art (watercolours) and decorative art (ceramics) also connects him to figures like William Morris or Walter Crane, who sought to break down hierarchies between different art forms.

Legacy and Recognition

William Stephen Coleman died in 1904 at the age of 75, following a prolonged illness. While his name may not be as instantly recognizable as some of the towering figures of Victorian art, his legacy endures through his diverse body of work. His paintings, illustrations, and ceramic designs contributed significantly to the visual culture of his time.

His works are held in several important public collections, including the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, the British Library, the Glasgow Art Gallery and Museum, and the Dudley Museum and Art Gallery. This institutional recognition underscores the quality and historical significance of his art. Furthermore, his watercolours and etchings continue to appear on the art market, often commanding respectable prices, indicating sustained interest among collectors.

Coleman represents a type of Victorian artist whose versatility allowed him to succeed across multiple disciplines. He was a skilled watercolourist admired for his delicate technique, a respected natural history illustrator who contributed to the scientific and popular appreciation of nature, and an innovative force in ceramic design through his directorship of the Minton Art Pottery Studio. His career reflects the interconnectedness of fine art, illustration, and decorative arts during a period of immense creative energy and change in Britain. He remains an important figure for understanding the nuances of Victorian naturalism and the breadth of the Aesthetic Movement.

Conclusion

William Stephen Coleman's journey from aspiring surgeon to accomplished artist encapsulates a dedication to beauty in its various forms. As an illustrator, he brought the natural world to life with precision and charm. As a watercolourist, he captured idyllic scenes and graceful figures with a distinctive, classically-inflected refinement. As a ceramic designer and director, he played a key role in the elevation of decorative arts through the Minton Art Pottery Studio. Though operating across fields sometimes viewed separately, Coleman's work consistently displays a sensitivity to form, colour, and the nuances of the natural world. He remains a significant contributor to the artistic landscape of Victorian Britain, a testament to the era's rich and multifaceted creative output.