Arnold Böcklin stands as a towering figure in the landscape of 19th-century European art, a Swiss painter whose work navigated the currents between Romanticism, Realism, and the burgeoning Symbolist movement. Born in Basel, Switzerland, on October 16, 1827, and passing away near Florence, Italy, on January 16, 1901, Böcklin's life spanned a period of significant artistic and cultural transformation. His canvases are renowned for their potent blend of mythological narratives, dreamlike atmospheres, and a profound, often melancholic, exploration of life, death, and the enigmatic power of nature. He remains a pivotal artist, recognized for his unique vision and his considerable influence on subsequent generations.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Böcklin's artistic journey began formally at the Düsseldorf Academy of Art. There, he studied under the landscape painter Johann Wilhelm Schirmer, a significant figure associated with the Düsseldorf school. Under Schirmer's guidance, Böcklin honed his technical skills, absorbing the prevailing influences of German Romanticism and the detailed observation inherent in Naturalism. This early training provided him with a solid foundation in landscape painting, a genre that would remain important throughout his career, albeit transformed by his evolving vision.

Seeking broader horizons and new influences, Böcklin embarked on travels through Germany and, crucially, to Italy. He also spent time in Paris, where he encountered the works of leading French artists. He was particularly impressed by the atmospheric landscapes of Camille Corot and the dramatic intensity of Eugène Delacroix. The Barbizon School's emphasis on painting outdoors (plein air) also resonated with him, encouraging a direct engagement with nature, although his interpretation would soon veer away from straightforward representation towards more subjective and imaginative ends. He also briefly studied with the prominent French painter Thomas Couture in Paris, further exposing him to the currents of French Romanticism and academic technique.

The Italian Revelation and Mythological Turn

The year 1850 marked a significant turning point when Böcklin first traveled to Rome. The Mediterranean world, with its ancient ruins, sun-drenched landscapes, and palpable connection to classical antiquity, profoundly affected him. The warmth and clarity of the Italian light began to permeate his canvases, replacing the often cooler palettes of his northern training. More importantly, Italy's rich mythological heritage ignited his imagination.

His work began to feature figures drawn from classical myth and legend, but imbued with his own distinct sensibility. Solitary shepherds, playful nymphs, satyrs, and wild, untamed centaurs started to populate his landscapes. These were not mere illustrations of ancient tales but rather explorations of primal forces, the relationship between humanity and nature, and the enduring power of myth. He often depicted these figures within dramatic natural settings, emphasizing the untamed aspects of both the landscape and its mythical inhabitants.

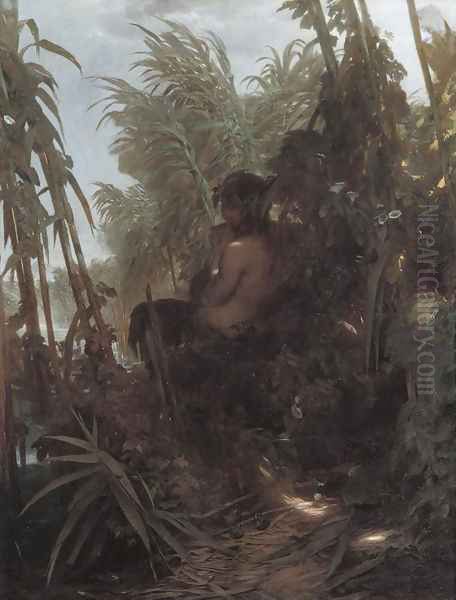

A key early success came in 1859 with his painting Pan in the Reeds (also known as Pan im Schilf). This work, depicting the goat-god Pan startlingly emerging from a dense thicket, captured the attention of King Ludwig I of Bavaria, who purchased it. This royal patronage significantly boosted Böcklin's reputation and brought his name to wider attention within the German-speaking art world, solidifying his path towards becoming a leading figure. Another notable work from this period, Pan Pursuing Syrinx (1857), further demonstrated his engagement with mythological themes, reinterpreting Ovid's tale with a characteristic blend of sensuality and wildness.

The Ascent of Symbolism

As Böcklin matured, his art increasingly moved away from the descriptive naturalism of his early years towards a more profound and personal Symbolism. While landscapes remained central, they became stages for exploring deeper psychological and philosophical themes. He became preoccupied with the elemental forces of nature, the complex and often fraught relationship between the sexes, the mysteries of human destiny, and the inescapable realities of mortality.

His paintings from this period often possess a brooding intensity and a dreamlike, sometimes unsettling, quality. He employed strong contrasts of light and shadow, dramatic compositions, and rich, often somber, color palettes to evoke powerful emotions and suggest hidden meanings. The natural world in his works is rarely benign; it is often depicted as powerful, indifferent, or even menacing, reflecting a Romantic sensibility filtered through a more modern, introspective lens.

Böcklin was also an innovator in terms of technique. He frequently experimented with different media, notably tempera painting, which allowed him to achieve smooth, enamel-like surfaces that enhanced the otherworldly quality of his images. He sought techniques that minimized visible brushstrokes, contributing to the static, dreamlike intensity of his compositions. There is also evidence suggesting he explored unconventional methods, possibly including collage elements or other experimental approaches, pushing the boundaries of traditional painting practice in his quest for expressive power.

Masterpiece: Isle of the Dead

Among Böcklin's extensive oeuvre, one work stands out with iconic status: Isle of the Dead (Die Toteninsel). He painted five versions of this composition between 1880 and 1886, each subtly different but sharing the same haunting core imagery. The painting depicts a desolate, rocky islet dominated by towering, dark cypress trees – traditional symbols of mourning and graveyards – rising from a somber, still sea. Carved into the sheer rock faces are what appear to be burial chambers or tombs.

Approaching the island is a small boat, rowed by a standing figure often interpreted as Charon, the ferryman of the dead in Greek mythology. In the boat, facing the island, stands a mysterious figure completely shrouded in white, often presumed to be a soul journeying to the afterlife, accompanied by a coffin-like object draped in white. The overall atmosphere is one of profound silence, stillness, melancholy, and an overwhelming sense of finality and transition.

Böcklin himself was somewhat enigmatic about the painting's precise meaning, famously stating it should evoke a feeling so profound that one would be disturbed by a knock on the door. While he acknowledged a commission request for "a picture to dream over," the specific symbolism remains open to interpretation. It is known that the English Cemetery in Florence, where his infant daughter Maria was buried, may have served as partial inspiration, particularly its tall cypress trees. The painting powerfully encapsulates themes central to Böcklin's work: mortality, the passage from life to death, the mystery of the afterlife, and the quiet solemnity of mourning. Its evocative power and ambiguous narrative have made it one of the most recognizable and frequently reproduced images in Symbolist art.

Other Major Works and Recurring Themes

While Isle of the Dead is his most famous work, Böcklin's exploration of symbolic themes extended across many other paintings. Plague (1898), for instance, personifies pestilence as a skeletal figure riding a winged beast through a medieval street, a terrifying vision of mass death and societal collapse that reflected late 19th-century anxieties. Odysseus and Calypso (1883) depicts the Homeric hero gazing longingly out to sea from the island where the nymph Calypso holds him captive, a powerful image of longing, isolation, and the allure of the unknown.

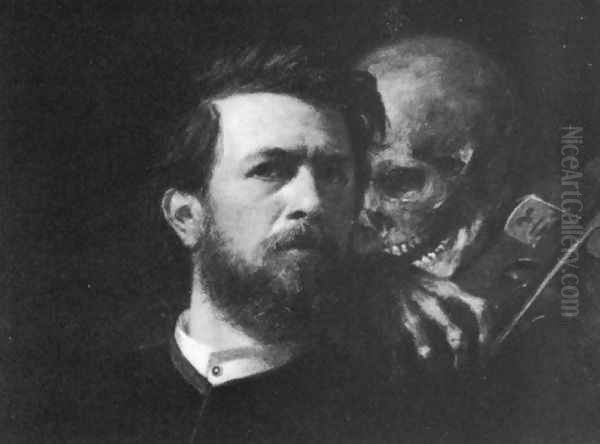

Mythological creatures remained a constant source of fascination. Centaurs, embodying the duality of human intellect and animal instinct, appear frequently, sometimes in idyllic scenes, other times in violent conflict (Battle of the Centaurs, 1873). Mermaids and tritons populate his dramatic seascapes (Playing in the Waves, 1883), representing the untamable power and mystery of the ocean. He also painted striking self-portraits, most famously Self-Portrait with Death Playing the Fiddle (1872), a chilling memento mori where a skeletal figure of Death plays a single-stringed violin directly behind the artist's ear as he pauses his work, a stark reminder of mortality's constant presence.

His landscapes, even without overt mythological figures, often carry a heavy symbolic weight. Ruined villas perched on cliffs, turbulent seas crashing against rocks, and silent, moonlit groves all contribute to an atmosphere charged with emotion and suggestive meaning. Böcklin masterfully used landscape not just as a backdrop, but as an active participant in the psychological drama of his paintings.

Artistic Circles and Contemporaries

Throughout his career, Böcklin moved within various artistic circles and interacted with numerous contemporaries, both influencing and being influenced by them. During his studies in Düsseldorf and later in Rome, he formed a close and lasting friendship with the German painter Anselm Feuerbach, another artist drawn to classical themes and the Italian landscape. Their shared experiences in Italy fostered mutual respect and artistic dialogue.

His time in Paris brought him into contact with the work, and possibly the person, of Camille Corot, whose atmospheric landscapes left an impression. He also studied under Thomas Couture, absorbing aspects of French academic tradition and Romanticism. In Munich, he associated with the painter Hans von Marées; Marées recognized Böcklin's talent and wrote appreciative commentary on his work, helping to build his reputation.

While living in Italy, Böcklin befriended the German writer and Nobel laureate Paul Heyse. Through Heyse, he likely gained introductions to a wider circle of artists and intellectuals residing in or visiting Italy. His powerful and often unsettling imagery resonated strongly with younger artists. The German painter and sculptor Franz von Stuck, a leading figure of Munich Secession and Symbolism, deeply admired Böcklin and created works clearly inspired by his mythological themes and dramatic style.

Another significant German Symbolist, Max Klinger, known for his intricate prints and sculptures, was profoundly influenced by Böcklin. Klinger even created a series of etchings titled "Fantasy on Böcklin's Isle of the Dead," demonstrating the direct impact of Böcklin's iconic painting. Böcklin also reportedly collaborated on some works with the German-American landscape painter Albert Bierstadt during time spent in Munich. His connections extended across the Atlantic, as evidenced by the American painter Charles Willson Peale, who is known to have collected Böcklin's work. Furthermore, the influential German sculptor and art theorist Adolf von Hildebrand expressed support for Böcklin's artistic innovations and methodological approach. These interactions place Böcklin firmly within the network of late 19th-century European artistic exchange.

Influence and Legacy

Arnold Böcklin's impact extended far beyond his own lifetime, resonating deeply with artists of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. He is widely regarded as a crucial precursor to several major modern art movements. His emphasis on subjective experience, dreamlike imagery, psychological depth, and the symbolic potential of myth and landscape laid groundwork for both Surrealism and certain strands of Expressionism.

Surrealist artists like Salvador Dalí and Giorgio de Chirico explicitly acknowledged Böcklin's influence. De Chirico's "Metaphysical Painting," with its enigmatic cityscapes, long shadows, and sense of unease, clearly echoes the atmosphere found in Böcklin's work, particularly Isle of the Dead. Dalí also admired Böcklin's ability to conjure unsettling, dreamlike realities. The Norwegian Expressionist Edvard Munch, whose work plumbed similar depths of psychological anxiety and mortality, was also significantly impacted by Böcklin; the haunting mood of Isle of the Dead finds resonance in Munch's own iconic explorations of existential dread, such as The Scream.

Other artists who drew inspiration from Böcklin include the Swiss Symbolist Ferdinand Hodler and the aforementioned German artists Max Klinger and Franz von Stuck. The Swiss-German modernist Paul Klee counted Böcklin among his favorite painters, appreciating his imaginative power. Even artists associated with different movements, like Marcel Duchamp, engaged with Böcklin's legacy, indicating his broad cultural presence.

Böcklin's influence was not confined to the visual arts. His evocative paintings captured the imagination of composers and writers. Most famously, the Russian composer Sergei Rachmaninoff was inspired by a black-and-white reproduction of Isle of the Dead to compose his symphonic poem of the same name (Op. 29, 1908), a work that masterfully translates the painting's somber atmosphere into music. The composer Max Reger also wrote "Four Tone Poems after Arnold Böcklin," Op. 128 (1913), directly referencing specific paintings. While claims of direct inspiration for figures like Richard Wagner or certain poets might be less substantiated, Böcklin's work undoubtedly permeated the cultural atmosphere of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, contributing to the era's fascination with myth, symbolism, and the subconscious.

Controversies and Reception

Despite his eventual acclaim, Böcklin's career was not without controversy, and his reception fluctuated over time. His decisive shift from more conventional Romantic landscapes to the darker, more personal, and often ambiguous themes of his Symbolist period was met with resistance from some contemporary critics. They found his later works obscure, overly literary, or even morbid, lacking the clarity and perceived objectivity valued in other artistic currents.

As Impressionism gained prominence in the 1880s and 1890s, focusing on capturing fleeting moments of light and modern life, Böcklin's art, rooted in mythology, allegory, and introspection, seemed increasingly out of step with the avant-garde to some observers. His reputation experienced periods of decline as tastes shifted towards modernism's different concerns.

More troublingly, Böcklin's work, particularly Isle of the Dead, was later appropriated and lauded during the Nazi era in Germany. Figures like Adolf Hitler admired the painting, viewing it (and Böcklin's art in general) as embodying a supposed Germanic spirit, praising its perceived seriousness and connection to themes of death and heroism. This politically motivated embrace inevitably cast a shadow over Böcklin's legacy in the post-war years, requiring a careful disentangling of the artist's work from its misuse.

However, beginning in the early 20th century and continuing after World War II, Böcklin's art underwent a critical reappraisal. Art historians and subsequent generations of artists recognized the profound originality of his vision and his crucial role in the development of Symbolism and his anticipation of Surrealism and Expressionism. His technical skill, imaginative power, and fearless exploration of the human psyche secured his position as a major figure in European art history.

Later Life and Enduring Significance

Böcklin spent much of his life moving between Switzerland, Germany, and Italy, finding particular inspiration in the latter. He held a professorship at the Weimar Saxon Grand Ducal Art School for a period and was involved in significant public commissions, including murals for the Kunstmuseum Basel. His life was marked by personal tragedy, including the deaths of several of his children, experiences that undoubtedly deepened the melancholic and mortality-focused aspects of his art.

In 1892, Böcklin suffered a stroke. Following this, he moved back to Italy, settling in a villa in San Domenico, near Fiesole, overlooking Florence. He continued to work, though likely at a reduced pace, until his death there in January 1901. He was buried in the Cimitero degli Allori, an evangelical cemetery in Florence, fittingly located not far from the English Cemetery that may have partly inspired his most famous work.

Arnold Böcklin remains a compelling and somewhat enigmatic figure. His art bridges the gap between the Romanticism of the early 19th century and the psychological explorations of early Modernism. He delved into the realms of myth, dream, and the subconscious, creating powerful images that continue to resonate with their blend of beauty, mystery, and profound melancholy. His willingness to confront themes of death, desire, and the overwhelming power of nature, combined with his distinctive visual language, ensures his enduring importance as a master of Symbolist painting. His works invite contemplation, offering not easy answers but evocative journeys into the deeper, often darker, landscapes of the human spirit.