Nikolaus Knüpfer stands as a fascinating figure in the rich tapestry of Dutch Golden Age painting. Though German by birth, he carved out a significant career in Utrecht, becoming a respected master known for his vibrant small-scale historical, biblical, and mythological scenes, as well as for being the teacher of several renowned artists, most notably Jan Steen and Gabriel Metsu. His work, characterized by lively compositions, expressive figures, and a distinctive use of color and light, offers a unique blend of influences and a personal vision that contributed to the diverse artistic landscape of the 17th century Netherlands.

Early Life and Artistic Beginnings

Nikolaus Knüpfer was born in Leipzig, likely around 1609, although some earlier sources suggested a birth year as early as 1603. The exact date remains somewhat elusive, a common challenge with artists of this period. His initial artistic training is believed to have taken place in his native Leipzig, where he was reportedly apprenticed to Emanuel Nysen (or Nyssen). Nysen himself is a somewhat obscure figure, which makes it difficult to ascertain the precise nature of Knüpfer's earliest stylistic influences. However, Leipzig, a significant trade city, would have offered exposure to various artistic currents, including lingering German Renaissance traditions and newer impulses from Italy and the Netherlands.

Following his apprenticeship, Knüpfer is documented as having moved to Magdeburg. There, his activities were not solely focused on painting; records indicate he was also engaged in making paintbrushes for other artists. This practical aspect of the art world suggests a hands-on understanding of materials, which would have served him well in his subsequent painting career. His time in Magdeburg seems to have been a transitional phase, lasting until approximately 1630.

Arrival and Establishment in Utrecht

Around 1630, Knüpfer made the pivotal decision to move to Utrecht in the Netherlands. This city was a vibrant artistic center, particularly known for the Utrecht Caravaggisti – painters like Gerrit van Honthorst, Hendrick ter Brugghen, and Dirck van Baburen – who had returned from Italy in the 1620s, bringing with them the dramatic chiaroscuro and naturalism of Caravaggio. While the peak of Caravaggism in Utrecht was slightly waning by 1630, its influence, particularly in terms of strong lighting and expressive realism, still permeated the city's artistic atmosphere.

Upon arriving in Utrecht, Knüpfer sought further instruction and found it with Abraham Bloemaert. Bloemaert was a highly respected and versatile master, one of the leading figures in Utrecht's art scene. His long career spanned various stylistic phases, from late Mannerism to an engagement with Caravaggist principles and a later, more classicizing style. Bloemaert's studio was a significant training ground, and his influence on Knüpfer is discernible, particularly in the animated figural compositions and sometimes elongated proportions seen in Knüpfer's earlier Utrecht works. Knüpfer is said to have worked with Bloemaert for about two years.

After this period of refinement under Bloemaert, Knüpfer established his own independent studio in Utrecht. He quickly gained recognition, and in 1637, he was admitted as a master into the Utrecht Guild of St. Luke. Membership in the guild was a crucial step for any artist wishing to operate professionally, take on apprentices, and sell their work openly. This marked his official establishment as a respected painter in the city.

Artistic Style and Thematic Concerns

Knüpfer developed a distinctive style, primarily focusing on small-scale cabinet paintings. These were intimate works intended for private collectors rather than large public or ecclesiastical commissions. His paintings are characterized by their lively, often crowded compositions, filled with expressive, gesticulating figures. He possessed a talent for narrative, imbuing his scenes with a sense of drama and animation.

His brushwork is often described as loose and spirited, contributing to the vibrancy of his surfaces. Knüpfer's palette was rich and varied, and he demonstrated a keen sensitivity to color harmonies. While he could employ strong chiaroscuro, reminiscent of the Utrecht Caravaggisti or the early works of Rembrandt van Rijn, his lighting often served to highlight the narrative and emotional core of the scene rather than merely creating dramatic effect. Indeed, some scholars have noted a kinship with Rembrandt's early Leiden period works, particularly in the dynamic compositions and the psychological intensity of the figures.

Knüpfer's thematic repertoire was diverse, though he showed a preference for historical, biblical (especially Old Testament), and mythological subjects. He also painted some genre scenes, which sometimes blurred the lines with his historical narratives due to their theatricality. Literary sources, including classical texts and contemporary plays, often provided inspiration for his works. The theatricality evident in many of his paintings – with figures arranged as if on a stage, often in multi-layered compositions – may reflect the influence of the local rhetoricians' chambers (rederijkerskamers) and their dramatic performances. These performances often utilized stepped stages, a feature sometimes echoed in Knüpfer's spatial arrangements.

He was particularly adept at conveying complex narratives within a confined space, using gesture, facial expression, and the interaction between figures to tell a story. His figures, though sometimes a little stocky or idiosyncratic in their anatomy, are always full of life and purpose. Moral and allegorical undertones were often present, appealing to the contemporary Dutch taste for art that was not only visually engaging but also edifying.

Key Commissions and Representative Works

While many of Knüpfer's works were destined for the private market, he did receive some notable commissions. Perhaps the most prestigious was from King Christian IV of Denmark, for whom he was commissioned to paint three battle scenes for Kronborg Castle. Unfortunately, these works are now lost, but the commission itself speaks to Knüpfer's reputation extending beyond Utrecht. He also reportedly painted landscapes, though these are less common or less securely attributed among his surviving oeuvre.

Several representative works illustrate Knüpfer's style and thematic preoccupations:

<em>Solon before Croesus</em> (c. 1650-1652, Getty Museum, Los Angeles): This painting depicts the famous story from Herodotus where the wise Athenian lawgiver Solon visits the fabulously wealthy King Croesus of Lydia. Croesus, expecting Solon to declare him the happiest of men, is instead told that true happiness can only be judged at the end of one's life. Knüpfer captures the moment of dialogue with expressive figures, rich costumes, and a crowded, opulent setting, typical of his narrative skill.

<em>The Queen of Sheba before Solomon</em> (various versions, e.g., Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg): This Old Testament subject was popular, allowing for depictions of exotic splendor and wisdom. Knüpfer’s versions are filled with intricate details, numerous attendants, and a focus on the interaction between the two main figures, showcasing his ability to manage complex group compositions.

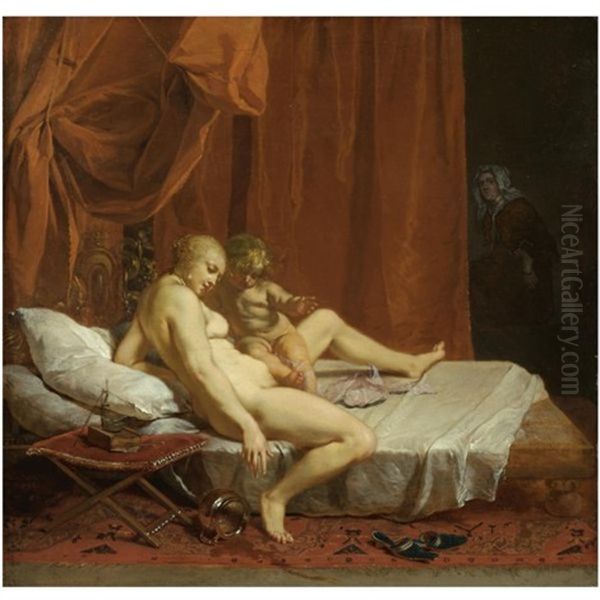

<em>Venus and Cupid</em> (c. 1640s, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York): This mythological scene displays Knüpfer's handling of the nude, albeit in a somewhat robust and less idealized manner than Italianate painters. The interaction between Venus and her son is rendered with a playful charm, set within a typically detailed environment.

<em>Hercules obtaining the Girdle of Hippolyta</em> (Musée du Louvre, Paris): This dynamic mythological scene showcases Knüpfer's ability to depict action and drama. The muscular figures and energetic composition are characteristic of his approach to such heroic tales.

<em>Zerubbabel and Darius</em> (Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg): Another Old Testament scene, this work likely depicts an episode from the Book of Ezra or related apocryphal texts, showcasing Knüpfer's interest in less commonly depicted biblical narratives. The rich colors and animated figures are typical of his style.

<em>Landscape with Mercury and Argus</em> (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna): While primarily a figure painter, this work demonstrates his ability to integrate mythological narratives within a landscape setting, a popular genre in Dutch art. The story of Mercury lulling Argus to sleep before slaying him is a classic Ovidian tale.

<em>The Adoration of the Magi</em> (e.g., Centraal Museum, Utrecht): A popular New Testament theme, Knüpfer’s interpretations are often characterized by a bustling crowd of figures, rich textures in the Magi's robes, and a sense of wonder, all rendered with his characteristic lively brushwork.

These works, and others like them, demonstrate Knüpfer's skill in creating small but impactful narrative paintings that were highly sought after by collectors. His ability to combine detailed storytelling with a painterly execution set him apart.

Knüpfer as a Teacher: Shaping the Next Generation

Beyond his own artistic output, Nikolaus Knüpfer played a crucial role as an educator. His studio in Utrecht attracted a number of talented pupils, the most famous of whom were Jan Steen and Gabriel Metsu. The influence he exerted on these artists, who would go on to become leading figures of the Dutch Golden Age, is a significant part of his legacy.

Jan Steen (c. 1626–1679): Steen, renowned for his lively and often humorous genre scenes, is documented as having studied with Knüpfer. While Steen's subject matter diverged from Knüpfer's predominantly historical and mythological focus, the influence of his teacher is evident. Knüpfer's skill in composing complex figural groups, his theatrical sense of narrative, and his ability to capture expressive gestures and interactions can be seen as foundational elements that Steen adapted and transformed for his own unique vision. The crowded, animated quality of many of Steen's "dissolute households" or festive gatherings owes a debt to Knüpfer's dynamic compositions. Steen also occasionally painted historical and biblical scenes, where the connection to Knüpfer's work is more direct.

Gabriel Metsu (1629–1667): Metsu, celebrated for his refined and elegant genre scenes, also spent time in Knüpfer's studio. In Metsu's earlier works, particularly his historical and biblical paintings, Knüpfer's influence is quite apparent in the choice of subject matter, the figural types, and the compositional arrangements. Although Metsu later developed a more polished and smooth technique, distinct from Knüpfer's looser brushwork, the grounding in narrative composition and figural expression gained from his teacher remained valuable. Some scholars also suggest Metsu may have studied with Jan Baptist Weenix, another Utrecht artist, possibly concurrently or subsequently, further enriching his artistic development.

The fact that two such prominent and stylistically distinct painters emerged from Knüpfer's workshop speaks to his quality as a teacher. He likely provided a strong foundation in the fundamentals of composition, narrative, and figural drawing, allowing his students to develop their own individual talents. Other, less famous painters, such as Ary de Vois, are also thought to have been his pupils.

Contextualizing Knüpfer: Contemporaries and Influences

Knüpfer's art did not develop in a vacuum. He was part of a vibrant artistic ecosystem in Utrecht and the broader Netherlands. His teacher, Abraham Bloemaert, was a towering figure whose influence extended to many artists, including Gerrit van Honthorst and Hendrick ter Brugghen, the leading Utrecht Caravaggisti. While Knüpfer was not a Caravaggisto in the strict sense, the general Utrecht atmosphere, shaped by these artists and Bloemaert's own engagement with Caravaggesque light and realism, undoubtedly left its mark.

The influence of Adam Elsheimer, a German painter active in Rome, is also often discussed in relation to Knüpfer, though likely indirectly. Elsheimer was renowned for his small-scale, meticulously detailed paintings on copper, often depicting biblical or mythological scenes within atmospheric landscapes. His work was highly influential on many Dutch artists, including Rembrandt's teacher Pieter Lastman, and subsequently on Rembrandt himself. Knüpfer's preference for small-scale, detailed narrative works aligns with this Elsheimerian tradition, which was transmitted through artists like Lastman and perhaps even Bloemaert.

Compared to Pieter Lastman (1583-1633), who was a generation older and a key figure in Amsterdam history painting, Knüpfer shared an interest in dramatic storytelling and expressive figures. However, Knüpfer's style was generally looser and more painterly than Lastman's more detailed and somewhat stiffer manner. Another contemporary working in a similar vein of small-scale history painting was Moyses van Wtenbrouck (c. 1600-1647), active in The Hague, whose idyllic landscapes with biblical or mythological figures share some common ground with Knüpfer's work.

In the broader context of Dutch art, which saw a rise in specialized genres like landscape (e.g., Jan van Goyen), portraiture (e.g., Frans Hals), and still life (e.g., Pieter Claesz), Knüpfer remained dedicated to history painting. This genre, though considered the highest in the academic hierarchy, was perhaps less dominant in the Dutch market than in Italy or Flanders. Knüpfer’s success lay in adapting these elevated subjects to the preferred cabinet-size format, making them suitable for domestic interiors.

His relationship with Rembrandt's style is also noteworthy. While there's no evidence of direct contact, the similarities in their early works – the dynamic compositions, the interest in psychological expression, and the use of chiaroscuro – suggest they were responding to similar artistic currents or that Knüpfer was aware of and admired the innovations of the Amsterdam master.

Other contemporaries in Utrecht included figure painters like Paulus Moreelse (also a renowned portraitist) and landscape painters such as Cornelis van Poelenburch and Jan Both, who specialized in Italianate landscapes. This diverse environment provided a rich backdrop for Knüpfer's own artistic development.

Later Years and Legacy

Nikolaus Knüpfer continued to live and work in Utrecht until his death. He was buried in the Buurkerk in Utrecht on October 15, 1655. His relatively early death, in his mid-forties, cut short a productive career.

Knüpfer's legacy is twofold. Firstly, there is his own body of work: distinctive, lively, and often charming narrative paintings that found a ready market among Dutch collectors. His ability to infuse small panels with dramatic energy and detailed storytelling was remarkable. His works are found today in major museums worldwide, including the Hermitage, the Louvre, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, attesting to their enduring appeal.

Secondly, and perhaps more significantly for the broader history of Dutch art, is his role as a teacher. By nurturing the talents of Jan Steen and Gabriel Metsu, he indirectly contributed to the development of Dutch genre painting, one of the towering achievements of the Golden Age. His influence on these masters, particularly in their formative years, underscores his importance as a transmitter of artistic knowledge and skill.

While perhaps not as widely known today as some of his contemporaries like Rembrandt or Vermeer, Nikolaus Knüpfer was a respected and successful artist in his own time. He represents a fascinating strand within Dutch Golden Age painting – a German émigré who absorbed and contributed to the artistic traditions of his adopted homeland, creating a body of work that is both individual and reflective of the rich artistic currents of 17th-century Utrecht. His paintings continue to engage viewers with their narrative vivacity and painterly charm, securing his place as a notable "kleinmeester" (little master) of significant talent and influence.

Conclusion

Nikolaus Knüpfer's journey from Leipzig to Utrecht, from an apprentice brush-maker to a respected master and influential teacher, is a testament to his artistic skill and adaptability. He successfully navigated the competitive art world of the Dutch Republic, creating a niche for himself with his spirited and engaging small-scale history paintings. His unique blend of German and Dutch influences, his connection to masters like Abraham Bloemaert, and his pivotal role in the education of Jan Steen and Gabriel Metsu, all contribute to his significance. As an art historian, one appreciates Knüpfer not only for the intrinsic quality of his works but also for the light he sheds on the interconnectedness of artistic training, patronage, and stylistic development during the Dutch Golden Age. His art remains a vibrant window into the narrative preoccupations and aesthetic tastes of his time.