Aert de Gelder stands as a significant, if sometimes underappreciated, figure in the annals of Dutch art. Born in Dordrecht on October 26, 1645, and passing away in the same city on August 27, 1727, his life and career bridged the twilight of the Dutch Golden Age and the nascent artistic sensibilities of the 18th century. His most profound claim to art historical fame is his status as one of the last, and arguably the most devoted, pupils of the great Rembrandt van Rijn. In an era when artistic tastes were shifting towards a more polished, classical, and internationally influenced Rococo style, De Gelder remained a steadfast adherent to the rich, expressive, and deeply human qualities of his master's late work, carrying Rembrandt's unique artistic DNA further into the new century than any other painter.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Dordrecht

Aert de Gelder's origins in Dordrecht, a historically significant trading city in South Holland, provided a solid foundation for his artistic pursuits. His father, Jan de Gelder, was a prosperous cooper who later held positions within the Dutch East India Company (VOC), indicating a family of comfortable means and social standing. This financial security likely afforded the young Aert the opportunity to pursue an artistic education without immediate commercial pressures, a privilege not available to all aspiring artists of his time.

His initial artistic training began under the tutelage of Samuel van Hoogstraten, himself a former pupil of Rembrandt and a multifaceted artist known for his illusionistic paintings, portraits, genre scenes, and art theoretical writings. Van Hoogstraten, who had returned to Dordrecht by 1656 after travels in Vienna, Rome, and London, would have imparted to De Gelder a solid grounding in the fundamentals of painting, perspective, and composition, likely imbued with Rembrandtesque principles he himself had absorbed. This early instruction in his hometown laid the groundwork for De Gelder's subsequent, more formative, period of study.

The Amsterdam Apprenticeship: In the Shadow of Rembrandt

Around 1661, Aert de Gelder made the pivotal decision to move to Amsterdam to study directly with Rembrandt van Rijn. By this time, Rembrandt, though still a towering figure, was experiencing financial difficulties and a decline in popular favor, as artistic tastes began to diverge from his increasingly personal and introspective style. Nevertheless, his studio still attracted ambitious young painters. De Gelder's apprenticeship, lasting approximately from 1661 to 1663 (some sources suggest until 1667, though the earlier dates are more commonly cited), placed him in the master's workshop during Rembrandt's late, most profound period.

This was a time when Rembrandt was producing masterpieces characterized by rich, dark tonalities, dramatic chiaroscuro, thickly applied impasto, and an unparalleled psychological depth in his figures. Works like The Syndics of the Drapers' Guild (1662) and his deeply moving late self-portraits exemplify the artistic environment in which De Gelder was immersed. He would have learned Rembrandt's techniques firsthand: the bold use of the brush, the experimental handling of paint (including scratching into wet paint with the brush handle or a palette knife), and the master's profound ability to convey human emotion and narrative through light and shadow. Unlike many of Rembrandt's other pupils, such as Ferdinand Bol or Govert Flinck, who later adapted their styles to suit prevailing, more elegant trends, De Gelder absorbed the essence of Rembrandt's late manner and remained remarkably faithful to it throughout his long career.

Artistic Style: A Legacy Honored and Personalized

Aert de Gelder's artistic style is inextricably linked to that of his master, Rembrandt. He is often cited as the only Dutch painter to continue working in Rembrandt's late style well into the 18th century, a period when it was largely out of fashion. This unwavering commitment makes his oeuvre a unique testament to the enduring power of Rembrandt's vision.

De Gelder's paintings are characterized by a warm, often golden-brown palette, dramatic lighting that sculpts figures from deep shadows, and a rich, tactile paint surface. He employed a broad, expressive brushstroke and was not afraid of using impasto to highlight certain areas, giving his works a textured, almost sculptural quality. His technique often involved unconventional methods, such as using his fingers, the palette knife, or the butt end of his brush to manipulate the paint, practices directly inherited from Rembrandt's experimental approach. This resulted in a looseness and freedom of handling that contrasted sharply with the smooth, highly finished surfaces favored by many of his contemporaries, such as the Leiden "Fijnschilders" like Gerrit Dou or Frans van Mieris the Elder.

While the Rembrandtesque foundation is undeniable, De Gelder was not a mere imitator. He developed his own distinct artistic personality. His compositions could be more theatrical and his figures sometimes possessed an exotic, almost fantastical quality, often adorned in elaborate, pseudo-oriental costumes and opulent jewelry. This fascination with rich textiles and accessories is a hallmark of his work, lending a particular vibrancy and narrative richness to his biblical and historical scenes. His color palette, while rooted in Rembrandt's warmth, could also incorporate brighter, more jewel-like hues, particularly in these costume elements.

Thematic Focus: Biblical Narratives and Portraiture

Like Rembrandt, Aert de Gelder demonstrated a profound engagement with biblical narratives. The Old and New Testaments provided the primary source material for many of his most significant works. He approached these sacred stories with a focus on their human drama and emotional core, rather than purely devotional or dogmatic representation. His figures, though often clad in historical or imaginative attire, convey relatable human emotions – contemplation, sorrow, surprise, devotion.

His depictions often highlight lesser-known or more intimate moments from biblical accounts, showcasing his deep familiarity with the scriptures. He had a particular fondness for stories from the Old Testament, including narratives featuring figures like Abraham, Esther, Judah, and David. In these works, he masterfully used light and shadow not just for dramatic effect, but to underscore the psychological state of his characters and the emotional tenor of the scene.

Portraiture was another important genre for De Gelder. While perhaps not as prolific a portraitist as some of his contemporaries like Frans Hals or Bartholomeus van der Helst, his portraits exhibit the same sensitivity and depth found in his narrative works. He captured not just the likeness but also the character of his sitters, often employing the Rembrandtesque play of light to model their features and convey a sense of inner life. His sitters were typically prominent citizens of Dordrecht, reflecting his established position within his local community.

Notable Works: Illuminating De Gelder's Artistry

Several key works exemplify Aert de Gelder's style and thematic preoccupations.

_The Baptism of Christ_ (c. 1710, Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge): This painting is one of De Gelder's most discussed works, partly due to its unusual depiction of a disc-like object in the sky emitting rays of light onto Christ and John the Baptist. While some modern interpretations have sensationally labeled this a "UFO," it is more accurately understood within the iconographic traditions of depicting divine light or heavenly apparitions, albeit in a particularly stylized manner. The figures are rendered with De Gelder's characteristic loose brushwork and warm tonality, emphasizing the spiritual significance of the moment.

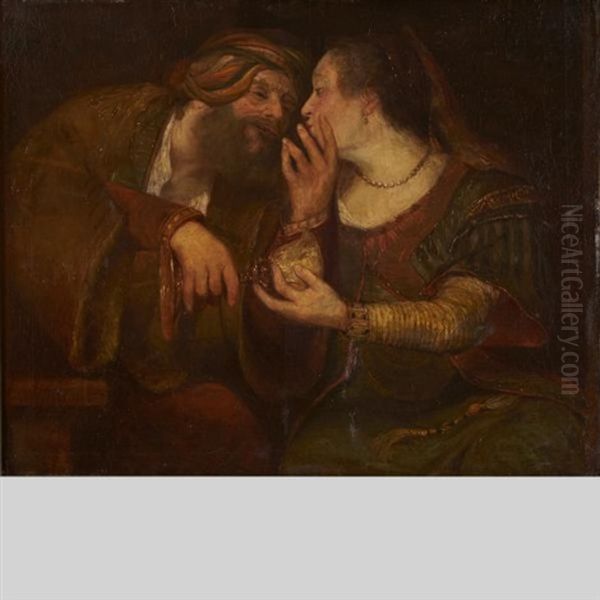

_Judah and Tamar_ (c. 1681, Mauritshuis, The Hague; another version c. 1700-1710, National Gallery of Ireland): This Old Testament subject, depicting a complex story of deception and lineage, was one De Gelder returned to. His treatment highlights the dramatic tension and moral ambiguity of the encounter. The figures are often shown in rich, textured garments, and the compositions are imbued with a sense of intimacy and psychological intrigue.

_Esther and Mordecai Writing the First Purim Letter_ (c. 1685, Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest; other Esther-themed works exist, such as _Esther at Her Toilette_): The story of Esther was a popular one, and De Gelder depicted various episodes. His paintings of Esther often emphasize her courage and wisdom, and he lavished attention on the opulent costumes and settings associated with the Persian court. _Esther at Her Toilette_ (Alte Pinakothek, Munich) showcases his skill in rendering luxurious fabrics and a reflective, intimate mood.

_Ahimelech Giving the Sword of Goliath to David_ (c. 1680s, J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles): This scene from the Book of Samuel captures a moment of solemn exchange. De Gelder's composition focuses on the interaction between the two main figures, using expressive gestures and a concentrated play of light to convey the gravity of the event. David's youth and Ahimelech's priestly authority are subtly suggested.

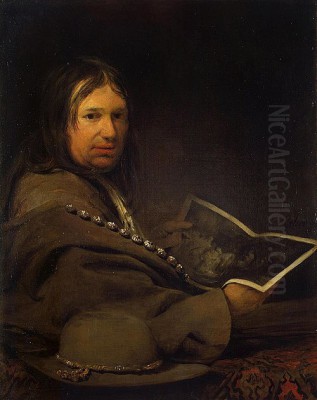

_Self-Portrait as Zeuxis_ (c. 1685, Städel Museum, Frankfurt): In this intriguing self-portrait, De Gelder depicts himself as the ancient Greek painter Zeuxis, who famously died laughing while painting a humorous portrait of an old woman. De Gelder shows himself in the act of painting, with a characteristic broad smile or laugh. It’s a work that reveals his wit and his identification with the artistic lineage of the past, a common trope among artists like Rembrandt himself (who also depicted himself as Zeuxis).

_Haman and Ahasuerus_ (or _Haman Begging Esther for Mercy_): This subject, often confused with Haman's condemnation before Ahasuerus, allowed De Gelder to explore themes of power, justice, and desperation. His renditions typically feature dramatic lighting and expressive figures, capturing the emotional intensity of the biblical narrative.

These works, among many others, demonstrate De Gelder's consistent adherence to Rembrandtesque principles while also showcasing his individual flair for color, texture, and narrative interpretation.

Life in Dordrecht: An Artist in His Community

After his formative years in Amsterdam, Aert de Gelder returned to his native Dordrecht, where he remained for the rest of his life. He became a respected member of the community and a leading artistic figure in the city. Unlike many artists who relied on guilds or constant commissions for survival, De Gelder's family wealth likely provided him with a degree of financial independence, allowing him to pursue his artistic vision with fewer commercial compromises.

He is documented as having connections with prominent local families and individuals, some of whom he portrayed. His father's involvement with the VOC might also have provided him with access to exotic objects or textiles that could have inspired the elaborate costumes in his paintings. While Dordrecht was no longer the primary artistic hub that Amsterdam had become, it still maintained a vibrant cultural life, and De Gelder was a central part of it. He is known to have painted a portrait of Hermanus Boerhaave, a famous Dutch physician and botanist, indicating his connections extended to learned circles.

There is little evidence to suggest that De Gelder undertook extensive travels after settling back in Dordrecht, nor did he seem to seek international fame in the manner of contemporaries like Adriaen van der Werff or Gerard de Lairesse, whose polished, classicizing styles were highly sought after by European courts. Instead, De Gelder cultivated his unique style in his hometown, a testament to his artistic conviction.

Contemporaries and Artistic Context

Aert de Gelder worked during a period of transition in Dutch art. The towering figures of the mid-17th century – Rembrandt, Frans Hals, Johannes Vermeer, Jacob van Ruisdael – were either deceased or, in Rembrandt's case, working in a style that was falling out of popular favor by the time De Gelder established his independent career.

His direct contemporaries included other Rembrandt pupils who took different paths. Nicolaes Maes, also from Dordrecht and a fellow student under Rembrandt, initially worked in a Rembrandtesque style but later shifted to a more elegant and colorful manner of portraiture that brought him considerable success. Ferdinand Bol and Govert Flinck similarly adapted their styles to meet the changing tastes for lighter, more refined aesthetics.

In contrast, De Gelder's steadfastness is remarkable. He can be seen as a counterpoint to the prevailing trends of the late 17th and early 18th centuries, which increasingly favored the clarity and grace of French Classicism or the detailed finish of the "Fijnschilders." Artists like Godfried Schalcken (known for his candlelit scenes) or Cornelis Bisschop (another Dordrecht painter) represented different facets of the diverse Dutch artistic landscape of the time. Schalcken, for instance, also studied with Van Hoogstraten and later with Gerrit Dou, developing a highly polished style quite distinct from De Gelder's.

De Gelder's commitment to Rembrandt's late style meant that while he was respected in Dordrecht, his work might have seemed somewhat anachronistic to patrons in larger centers like Amsterdam or The Hague, who were increasingly drawn to the more fashionable international styles. However, this very "unfashionableness" is what makes him so crucial for understanding the long afterlife of Rembrandt's influence.

Anecdotes, Controversies, and Character

Relatively few personal anecdotes about Aert de Gelder have survived, which is common for many artists of his era unless they were subjects of early biographers like Arnold Houbraken (who does mention De Gelder, noting him as Rembrandt's last pupil and praising his manner of painting).

The "UFO" in The Baptism of Christ remains the most frequently cited curiosity associated with his work, sparking considerable debate outside of mainstream art historical circles. Within art history, the discussion focuses more on iconographic precedents for depicting divine intervention and light.

There has been some scholarly debate regarding the precise duration and nature of his apprenticeship with Rembrandt. While the general consensus affirms his status as a pupil, the exact years and the extent to which he might have been more of a studio assistant in Rembrandt's later, more financially strained years, are points of nuanced discussion. However, the profound stylistic debt is undeniable.

His Self-Portrait as Zeuxis suggests a man with a sense of humor and an awareness of his place within art history. The choice of Zeuxis, known for his realism but also for the anecdote of his death by laughter, hints at a complex artistic persona. He was known to be unmarried for most of his life, only marrying at the age of 68, in 1713, to Maria van der Hulst, though this union was short-lived as she passed away a few years later. He did not have children.

Later Years, Death, and Legacy

Aert de Gelder continued to paint actively into his later years, maintaining his characteristic style. He passed away in Dordrecht on August 27, 1727, at the advanced age of 81. He was buried in the Grote Kerk (Great Church) in Dordrecht.

His immediate impact on the generation of artists that followed him was perhaps limited, given that his style was already out of step with the prevailing Rococo and early Neoclassical trends of the 18th century. However, his significance has grown with historical perspective. Art historians now recognize him as a vital link to Rembrandt, a preserver of a unique artistic tradition that might otherwise have faded more quickly. His works provide invaluable insight into the techniques and artistic philosophy of Rembrandt's late period, as seen through the eyes of a devoted and talented pupil.

In the 19th century, with the Romantic re-evaluation of Rembrandt and a renewed appreciation for expressive individualism in art, figures like De Gelder began to attract more attention. His rich textures, dramatic lighting, and emotional depth resonated with new artistic sensibilities. Today, his paintings are held in major museums around the world, and he is acknowledged as an important and original master in his own right, not merely a follower. His works stand as a testament to the enduring power of Rembrandt's genius and to De Gelder's own unwavering artistic integrity in continuing that legacy. He ensured that the embers of Rembrandt's fiery, humanistic art continued to glow long after the master himself had departed.

Conclusion: The Unwavering Vision of Aert de Gelder

Aert de Gelder occupies a unique niche in Dutch art history. As Rembrandt's last significant pupil, he became the custodian of a powerful, deeply personal artistic style that was increasingly at odds with the fashionable trends of his time. His decision to remain true to his master's late manner, rather than adapting to more commercially viable aesthetics, speaks to a profound artistic conviction. Through his rich, expressive brushwork, his dramatic use of chiaroscuro, his warm palette, and his humanizing approach to biblical narratives and portraiture, De Gelder not only honored Rembrandt's legacy but also forged a distinctive artistic identity.

His works, from the intriguing Baptism of Christ to the emotionally charged scenes from the Old Testament and his insightful portraits, reveal an artist of considerable skill and sensitivity. Living and working primarily in his native Dordrecht, he may not have achieved the widespread contemporary fame of some of his peers, but his enduring commitment to a deeply personal and expressive mode of painting ensures his lasting importance. Aert de Gelder stands as a vital bridge, carrying the profound artistic spirit of the Dutch Golden Age, and particularly the singular genius of Rembrandt, into the 18th century, leaving behind a body of work that continues to captivate and move viewers today.