Willem de Poorter stands as an intriguing, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the rich tapestry of Dutch Golden Age painting. Active during the first half of the 17th century, he navigated the bustling artistic centers of the Netherlands, primarily Haarlem, producing works that spanned religious narratives, mythological scenes, historical allegories, and evocative still lifes. His career is often discussed in relation to the towering figure of Rembrandt van Rijn, with ongoing scholarly debate about the nature and extent of their connection. This exploration delves into De Poorter's life, his artistic development, his significant works, and his place within the vibrant artistic milieu of his time.

Early Life and Flemish Roots

Willem de Poorter was born in 1608, likely in Haarlem, though the exact location is not definitively established. A significant aspect of his background was his family's Flemish heritage. His father, Pieter de Poorter, hailed from Flanders, a region with a distinct and influential artistic tradition. This connection to the Southern Netherlands may have subtly informed Willem's artistic sensibilities, even as he matured within the Dutch artistic environment. Flanders, particularly Antwerp, had been a dominant artistic force, with masters like Peter Paul Rubens and Jacob Jordaens shaping Baroque art. While De Poorter's style would align more with Dutch trends, this familial link is a noteworthy part of his biography.

The early 17th century was a period of significant migration, with many individuals and families moving from the Southern Netherlands (then under Spanish rule) to the more prosperous and religiously tolerant Dutch Republic. This influx of talent and diverse cultural perspectives contributed to the dynamism of the Dutch Golden Age.

Artistic Formation in Haarlem

De Poorter's artistic career primarily unfolded in Haarlem, a city that, alongside Amsterdam, Utrecht, and Delft, was a major center for painting in the Dutch Republic. Haarlem had a long-standing artistic tradition, home to influential figures like Hendrick Goltzius, a master of late Mannerism, and later, Frans Hals, renowned for his lively portraits. The city's artistic environment was characterized by a diversity of genres and styles.

Willem de Poorter is first documented as an active painter in Haarlem around 1631. By 1634, he had achieved the status of a master painter and is recorded as taking on his own pupil, Pieter Casteleijn. This indicates that he had established a reputation and a workshop capable of training younger artists. His early works from this period suggest an artist absorbing the prevailing trends in Haarlem, particularly in history painting, which often drew on biblical and classical narratives. Artists like Pieter de Grebber and Hendrik Gerritsz Pot were active in Haarlem and contributed to the local idiom of history painting, which De Poorter would have been familiar with.

The Rembrandt Question: Student or Follower?

One of the most debated aspects of Willem de Poorter's career is his relationship with Rembrandt van Rijn. Some art historians have proposed that De Poorter may have been a student of Rembrandt, possibly during Rembrandt's early years in Leiden or shortly after his move to Amsterdam around 1631-1632. This theory is largely based on stylistic similarities observed between De Poorter's works from the 1630s and those of Rembrandt. De Poorter's adoption of dramatic chiaroscuro (the strong contrast between light and dark), his interest in expressive figures, and his choice of Old Testament themes are often cited as evidence of Rembrandt's influence.

However, concrete documentary evidence for a formal apprenticeship is lacking. Other scholars argue that De Poorter's style, while showing an awareness of Rembrandt's innovations, developed more independently within the Haarlem school. They suggest that his early works align more closely with Haarlem-based artists before a more pronounced "Rembrandtesque" phase emerged in the mid-1630s. It's plausible that De Poorter, like many ambitious young painters of his time, was keenly aware of Rembrandt's rising fame and groundbreaking style and sought to emulate aspects of it without necessarily being a direct pupil. The artistic exchange was fluid, and successful formulas were often adopted and adapted by contemporaries.

Rembrandt himself had been a student of Pieter Lastman in Amsterdam, who specialized in history painting with an emphasis on clear narrative and rich detail. Lastman's influence on Rembrandt is evident, and it's possible that De Poorter was also looking at similar sources, or at Rembrandt's interpretation of those sources. The debate underscores the challenge of reconstructing artistic lineages based solely on stylistic analysis, especially in an era of intense artistic cross-pollination.

Thematic Focus: Religion, Mythology, and History

Willem de Poorter's oeuvre is characterized by a strong focus on narrative subjects, primarily drawn from the Bible, classical mythology, and historical accounts. These "history paintings" were considered the most prestigious genre in the art hierarchy of the time, demanding skill in composition, figure drawing, and the depiction of human emotion.

His biblical scenes often favored dramatic Old Testament stories, such as Samson and Delilah and The Idolatry of Solomon. These subjects allowed for rich characterization, elaborate costumes, and the exploration of moral and theological themes. The Idolatry of Solomon, for instance, depicts the aged king being led astray by his foreign wives to worship idols, a popular cautionary tale. De Poorter’s handling of such scenes often involved a compact composition, with figures grouped closely, and a focused light source heightening the drama.

Mythological subjects also featured in his work, such as Tarquinius Finding Lucretia at Work. These stories from classical antiquity provided opportunities for depicting heroic or tragic narratives, often with an underlying moral message. His historical scenes, sometimes allegorical, also reflected contemporary concerns or timeless human dramas.

Signature Style: Light, Detail, and Intimacy

De Poorter's artistic style, while evolving, exhibits several consistent characteristics. He typically worked on a relatively small scale, creating cabinet-sized paintings suited for private collectors rather than large public commissions. This intimacy is a hallmark of much of his output.

A key feature is his use of light. Often employing a strong chiaroscuro, he would illuminate the central figures or action while allowing the background to recede into shadow. This technique, famously mastered by Rembrandt and Caravaggio before him, created a sense of drama and focused the viewer's attention. His lighting is often warm, with golden or reddish tones contributing to the atmosphere of his scenes.

His paintings are generally characterized by a meticulous attention to detail, particularly in the rendering of fabrics, armor, and still life elements within his narrative scenes. This careful execution is evident in the textures of velvet cloaks, the gleam of metal, and the intricate patterns of objects. This precision, combined with a rich, often jewel-like palette, gives his works a precious quality.

The figures in De Poorter's paintings, while sometimes appearing somewhat stiff or doll-like compared to the dynamism of a master like Rubens, often convey a sense of earnest emotion. He paid attention to facial expressions and gestures to communicate the narrative. His compositions are typically well-structured, often with a triangular or diagonal arrangement of figures to create a sense of order and focus.

Notable Works: A Closer Look

Several paintings stand out as representative of Willem de Poorter's skill and thematic preoccupations.

The Idolatry of Solomon (various versions, one in the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam): This is a recurring theme in his work. Typically, Solomon is shown before an altar, often with one of his wives gesturing towards an idol. De Poorter uses rich colors for the king's robes and a focused light to highlight the central group, contrasting with the shadowy temple interior. The work explores themes of wisdom, temptation, and divine judgment.

Samson and Delilah (c. early 1630s, Gemäldegalerie, Berlin): This dramatic biblical story of betrayal was a popular subject. De Poorter captures the tense moment as Delilah has Samson's hair shorn, robbing him of his strength. The interplay of light and shadow, the expressive, if somewhat theatrical, gestures, and the rich textures are characteristic of his approach.

St Paul and St Barnabas at Lystra (1636, National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.): This painting depicts an episode from the Acts of the Apostles where the people of Lystra attempt to worship Paul and Barnabas as gods. De Poorter creates a bustling scene with numerous figures, showcasing his ability to manage complex compositions on a small scale. The classical architecture and varied reactions of the crowd are carefully rendered.

Tarquinius Finding Lucretia at Work (1633, Musée des Augustins, Toulouse): This scene from Roman history, a prelude to Lucretia's tragic fate, shows De Poorter's engagement with classical narratives. The interior setting, the detailed depiction of Lucretia and her attendants engaged in domestic virtue, and the ominous arrival of Tarquinius are typical of his narrative style.

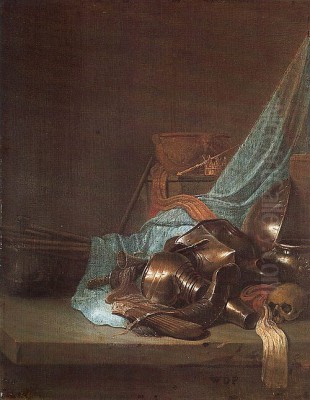

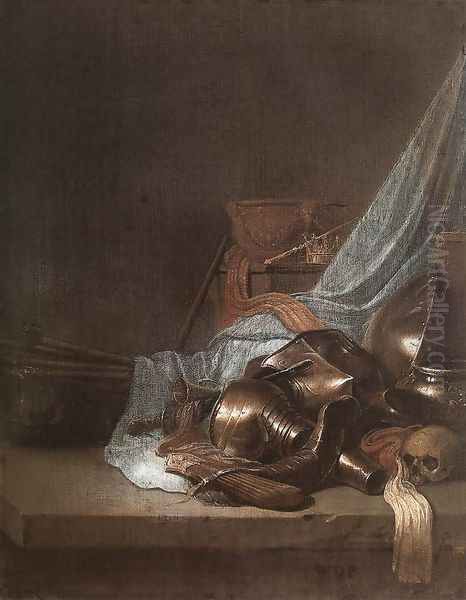

Still-Life with Weapons and Banners (1636, Herzog Anton Ulrich Museum, Brunswick): While primarily a history painter, De Poorter also produced striking still lifes. This particular work is a vanitas still life, filled with symbols of warfare – armor, helmets, swords, drums, and banners. The inclusion of a skull subtly hints at the transience of military glory and the devastation of conflict, possibly alluding to the ongoing Thirty Years' War (1618-1648) or the Eighty Years' War (1568-1648) from which the Dutch Republic had emerged. Such still lifes, often termed pronkstilleven (ostentatious still lifes) when featuring luxurious objects, were a Dutch specialty, and De Poorter’s contribution here is significant. His skill in rendering metallic surfaces is particularly evident.

Simeon's Song of Praise (c. early 1640s, Mauritshuis, The Hague): Also known as the Presentation in the Temple, this New Testament scene shows the aged Simeon recognizing the infant Jesus as the Messiah. De Poorter's version is intimate and reverent, with a soft, focused light on the central figures. It echoes Rembrandt's own treatments of this subject in its emotional depth and use of chiaroscuro.

The Resurrection of Lazarus (c. early 1640s, Alte Pinakothek, Munich): Another theme tackled by Rembrandt, De Poorter’s rendition shows Christ commanding Lazarus to rise from the tomb. The dramatic gestures, the astonished onlookers, and the play of light emerging from the darkness of the tomb are key elements.

Later Career and Move from Haarlem

Willem de Poorter remained active in Haarlem for a significant portion of his career. He is last recorded in the archives of the Haarlem Guild of St. Luke in 1645. Around this time, he moved to Wijk bij Heusden, a smaller town. The reasons for this move are not entirely clear; perhaps it was for personal reasons or due to shifting patronage opportunities.

His artistic output seems to have continued, though perhaps at a different pace or with a different focus. He died around 1648, or possibly later, with some sources suggesting as late as 1668, though the earlier date is more commonly accepted. His relatively short active period, spanning roughly two decades, and his move away from a major artistic center may have contributed to his subsequent relative obscurity compared to contemporaries who remained in cities like Amsterdam or Leiden.

Interactions with Other Artists

Beyond the Rembrandt connection, De Poorter would have interacted with numerous artists in Haarlem. The city's Guild of St. Luke was a hub for painters, sculptors, and craftsmen. He would have known the work of, and possibly known personally, figures like:

Frans Hals (1582/83–1666): The leading portraitist in Haarlem.

Adriaen Brouwer (c. 1605–1638): Though Flemish, Brouwer worked in Haarlem for a period, known for his peasant genre scenes.

Adriaen van Ostade (1610–1685): A prolific painter of peasant life, also active in Haarlem.

Judith Leyster (1609–1660): One of the few recognized female painters of the era, active in Haarlem, known for genre scenes and portraits.

Pieter Claesz (c. 1597–1660) and Willem Claesz Heda (1594–c. 1680): Masters of the monochrome still life, a Haarlem specialty. De Poorter’s still life work, though different in subject, shows a similar Dutch preoccupation with texture and symbolism.

Salomon van Ruysdael (c. 1602–1670) and Jan van Goyen (1596–1656): Leading landscape painters, though this was not De Poorter's genre.

Jacob de Wet (c. 1610–c. 1675): Another Haarlem painter of biblical and historical scenes, whose style sometimes shows parallels with De Poorter's, and with whom he may have shared learning experiences.

The influence of earlier Haarlem masters like Hendrick Goltzius (1558–1617) and Karel van Mander (1548–1606), who was an important theorist and painter, would have still been felt through their pupils and the artistic traditions they established.

If De Poorter did spend time in Amsterdam, he might have encountered artists in Rembrandt’s circle, such as Govert Flinck (1615–1660) or Ferdinand Bol (1616–1680), who were actual pupils of Rembrandt and successfully propagated his style. He may also have been aware of Jan Lievens (1607–1674), Rembrandt's early associate in Leiden, whose work also showed a powerful use of chiaroscuro.

Historical Evaluation and Legacy

For a long period, Willem de Poorter was a relatively minor name in art historical surveys of the Dutch Golden Age. His work was sometimes confused with or attributed to other artists, including Rembrandt or his pupils. However, modern scholarship has increasingly recognized his distinct contribution, particularly his skill in small-scale history painting and his unique still lifes.

His historical evaluation is complex. He was clearly a talented painter, adept at composition, color, and the rendering of detail. His engagement with Rembrandtesque lighting and psychological intensity marks him as an artist responsive to the most innovative trends of his time. Yet, he did not achieve the same level of fame or influence as Rembrandt or other leading masters.

His legacy lies in a body of work that exemplifies many characteristics of Dutch Golden Age art: the interest in biblical narrative (interpreted through a Protestant lens, though Old Testament themes had broader appeal), the fascination with classical antiquity, the moralizing intent often embedded in his scenes, and the exceptional skill in rendering the material world. His Still-Life with Weapons and Banners is a particularly powerful example of the Dutch vanitas tradition, conveying complex allegorical meaning through meticulously depicted objects.

Today, Willem de Poorter's paintings are found in numerous prestigious museums across Europe and North America, including the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, the Mauritshuis in The Hague, the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin, the Alte Pinakothek in Munich, and the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C. This presence in major collections attests to a growing appreciation of his artistic merits.

Conclusion: A Distinct Voice in a Golden Age

Willem de Poorter emerges as a skilled and thoughtful painter who carved out a niche for himself within the competitive art world of the Dutch Golden Age. While the shadow of Rembrandt looms large over many artists of this period, De Poorter, whether a direct pupil or an inspired contemporary, absorbed and reinterpreted prevailing stylistic trends to create a body of work with its own distinct character. His preference for intimate, jewel-like narrative paintings, his dramatic use of light, and his meticulous attention to detail define his artistic personality.

His exploration of religious, mythological, and historical themes contributed to the rich iconographic landscape of 17th-century Dutch art. His still lifes, though fewer in number, demonstrate his versatility and his ability to imbue inanimate objects with profound symbolic meaning. As art historical research continues to uncover the nuances of this incredibly fertile period, Willem de Poorter's contributions are increasingly valued, securing his place as a noteworthy master of the Dutch Golden Age, an artist who successfully navigated the artistic currents of Haarlem and beyond, leaving behind a legacy of finely crafted and intellectually engaging works.