Suze Bisschop-Robertson (1855–1922) stands as a pivotal figure in Dutch art history, a painter whose robust, expressive style and unwavering dedication to her vision carved a unique path during a transformative period. Active predominantly in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, she navigated the currents of Impressionism and emerging modernism, distinguishing herself with a powerful artistic voice that often diverged from the more subdued aesthetics of her contemporaries, including many within the Hague School. Her work, characterized by bold brushwork, a somber yet rich palette, and a profound empathy for her subjects—primarily working-class women—contributed significantly to the fabric of Dutch modern art and helped pave the way for subsequent generations of female artists.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Susanne (Suze) Robertson was born on December 17, 1855, in The Hague, Netherlands, into a family with commercial and artistic inclinations. Her father, John Robertson, was a merchant, and while not a painter himself, the family environment was one that appreciated culture. This atmosphere likely nurtured her early interest in art. Recognizing her talent, she embarked on formal artistic training, a significant step for a woman of her time.

She initially studied at the Royal Academy of Art in The Hague, where she would have been exposed to the prevailing academic traditions. Later, she also received instruction in Rotterdam, notably from artists like Petrus van der Velden, before further honing her skills in Amsterdam. Her education provided her with a solid technical foundation, but her artistic spirit yearned for a more personal and expressive mode of representation, moving beyond purely academic constraints. This period was crucial in shaping her resolve to become a professional artist, a challenging ambition in an era when women's roles were largely confined to the domestic sphere.

Forging an Independent Artistic Path

Robertson's early career was marked by a fierce determination to establish herself as an independent artist. She initially took up a teaching position at a girls' school in Rotterdam, a common path for women with artistic training. However, her true passion lay in her own creative output. She was known for her strong will and an unwillingness to compromise her artistic integrity for commercial appeal or prevailing tastes. This independence was a hallmark of her personality and her art.

Her style began to diverge significantly from the picturesque and often romanticized output of many Hague School painters. While artists like Jozef Israëls, Anton Mauve, and the Maris brothers (Jacob, Matthijs, and Willem) were celebrated for their atmospheric landscapes and genre scenes, Robertson's work possessed a rawness and emotional intensity that set her apart. She was less concerned with idyllic beauty and more focused on the underlying truth and dignity of her subjects.

Artistic Style and Thematic Concerns

Suze Bisschop-Robertson’s artistic style is characterized by its vigor, its tactile quality, and its profound psychological depth. She developed a highly personal visual language that resonated with the burgeoning modernist sensibilities of the era, even while retaining a strong connection to figurative representation.

Subject Matter: The Lives of Ordinary Women

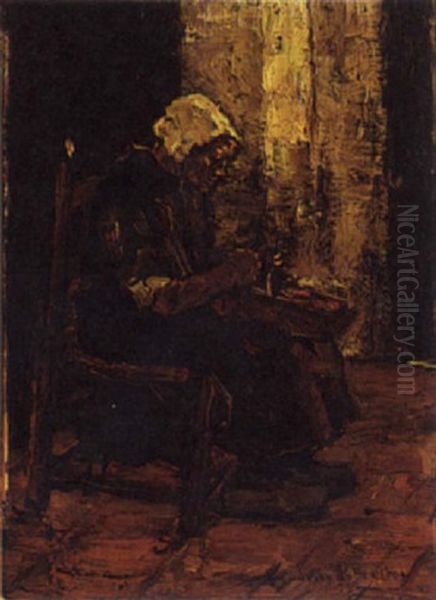

A defining feature of Robertson's oeuvre is her consistent focus on the lives of ordinary women, particularly those from the working class. She depicted laundresses, farm women, mothers with children, and solitary female figures engaged in domestic labor or quiet contemplation. These were not idealized or sentimentalized portrayals; instead, she imbued her subjects with a sense of gravity and resilience. Works like Handwerkende boerin (Peasant Woman Doing Needlework) or Kop van een boerin (Katrijn) (Head of a Peasant Woman (Katrijn)) showcase her empathy and her ability to capture the inner life of her sitters. This thematic choice was radical for its time, elevating the everyday experiences of marginalized women to the realm of serious art.

Color and Brushwork: An Expressive Force

Robertson's use of color was distinctive. She often employed a palette of deep, earthy tones—browns, ochres, grays, and muted blues and greens—punctuated by moments of surprising vibrancy. Her colors were not merely descriptive but were integral to the emotional impact of her paintings. She applied paint with bold, often thick, impasto strokes, giving her canvases a textured, almost sculptural quality. This robust brushwork conveyed a sense of energy and immediacy, reflecting the physicality of her subjects' lives and her own passionate engagement with her medium. This approach contrasted with the finer, more blended brushwork often seen in traditional academic painting or the lighter touch of many Impressionists.

Material Experimentation

While primarily an oil painter, Robertson was also known to experiment with materials and techniques. There are accounts of her incorporating unconventional elements into her work, seeking new ways to enhance texture and expression. This willingness to explore beyond traditional boundaries further underscores her modernist spirit and her commitment to finding the most effective means to convey her artistic vision. Her drawings, too, possess a similar strength and directness, revealing a masterful command of line and form.

Key Influences and Artistic Dialogue

Suze Bisschop-Robertson's art did not develop in a vacuum. She was keenly aware of the artistic currents of her time and drew inspiration from various sources, while always transforming these influences into something uniquely her own.

One of the most significant, albeit perhaps indirect, influences often cited in connection with Robertson is Vincent van Gogh. Although their direct interaction is not documented, her work shares with Van Gogh's a profound emotional intensity, a focus on the lives of common people, and an expressive use of color and brushwork. Like Van Gogh, she sought to convey the inner essence of her subjects rather than just their external appearance. Her powerful, sometimes somber, depictions of peasant life resonate with Van Gogh's Nuenen period.

The Italian painter Antonio Mancini, known for his rich impasto and vibrant, psychologically charged portraits, is another artist whose work may have resonated with Robertson's sensibilities. Mancini's bold technique and his ability to capture the character of his sitters could have provided a point of reference for her own explorations in portraiture and figure painting.

While distinct from the mainstream Hague School, she was certainly aware of its leading figures and their achievements. Her husband, Richard Bisschop, was associated with this school. However, Suze Robertson pushed beyond the often more tranquil and atmospheric qualities of the Hague School, opting for a more rugged and emotionally direct form of realism that bordered on expressionism. Her work can be seen as a bridge between the 19th-century realist traditions and the more subjective approaches of 20th-century modernism.

Marriage and Continued Artistic Identity

In 1892, Suze Robertson married the painter Richard Bisschop (1849–1926). Richard was an established artist, known for his church interiors and genre scenes, often working within the Hague School tradition. Marriage for female artists of that era could often mean the curtailment of their careers. However, Suze Bisschop-Robertson continued to paint prolifically and exhibit under her own name, often as "Suze Robertson" or "S. Bisschop-Robertson," asserting her continued artistic identity.

Their home in The Hague became a gathering place for artists and intellectuals. While Richard's style was more conventional, there seems to have been mutual respect for each other's work. Suze's unwavering commitment to her distinct artistic vision persisted throughout her marriage, indicating a strong sense of self and purpose.

The Amsterdam Joffers and Wider Artistic Circles

Suze Bisschop-Robertson was also connected to the group of women artists known as the "Amsterdamse Joffers" (Amsterdam Young Women). This was not a formal school or movement with a unified style, but rather a collective term for a group of women painters who were friends and contemporaries, active in Amsterdam around the turn of the 20th century. Prominent members included Lizzy Ansingh, Marie van Regteren Altena, Coba Ritsema, Ans van den Berg, Jacoba Surie, Nelly Bodenheim, Betsy Westendorp-Osieck, and Jo Bauer-Stumpff.

While Robertson was somewhat older and her style often more rugged and expressionistic than the typically more refined, Impressionist-influenced work of many Joffers, she shared with them the experience of being a professional woman artist in a male-dominated art world. Her association with this group, however loose, highlights her place within the growing community of female artists in the Netherlands who were asserting their presence and talent.

Her work was exhibited at various venues, including the Pulchri Studio in The Hague, an important artists' society co-founded by figures like Hendrik Willem Mesdag and Sientje van Houten (who was also an artist and collector, and whose collection included works by Robertson). She also participated in the "Exhibitions of Living Masters" (Tentoonstellingen van Levende Meesters), which were crucial platforms for contemporary artists. Her engagement with these institutions, despite her often unconventional style, demonstrates her active participation in the Dutch art scene. She would have been aware of contemporaries like George Hendrik Breitner and Isaac Israëls, leading figures of Amsterdam Impressionism, whose depictions of urban life, though different in focus, shared a certain dynamism. The Symbolist and Art Nouveau innovations of Jan Toorop also formed part of the rich artistic tapestry of the period.

Notable Works: A Closer Look

Several works stand out in Suze Bisschop-Robertson's oeuvre, exemplifying her unique style and thematic preoccupations.

Binnenplaats (Noordwijk) (Courtyard at Noordwijk), painted around 1905, is a powerful example of her ability to transform an ordinary scene into a composition of great visual and emotional strength. The play of light and shadow, the robust forms of the buildings, and the textured application of paint create a dynamic and evocative image.

Twee oude huizen (Two Old Houses), from circa 1911-1912, showcases her interest in vernacular architecture and her ability to imbue inanimate structures with a sense of character and history. The houses are not merely depicted; they seem to possess a life of their own, rendered with her characteristic bold brushwork.

Her portraits and figure studies of peasant women, such as Kop van een boerin (Katrijn) and Handwerkende boerin, are among her most compelling works. These paintings go beyond mere representation, capturing the weariness, strength, and quiet dignity of women whose lives were often characterized by hard labor. The faces are often deeply lined, the hands strong and capable, rendered with an unflinching honesty.

De visvangst van Harderwijk (The Fish Catch of Harderwijk) is noted as one of her works that aligns more closely with an Impressionistic sensibility, likely capturing the fleeting effects of light and atmosphere associated with the fishing industry. However, even here, her characteristic vigor would likely be present.

Another significant work often mentioned is Bleekveld in Leur (Bleaching Field in Leur). This subject, women laying out linen to bleach in the sun, was a common one in Dutch art, but Robertson would have approached it with her signature intensity, focusing on the labor and the figures within the landscape rather than just the picturesque qualities of the scene.

Challenges, Recognition, and Late Career

Like many women artists of her time, Suze Bisschop-Robertson faced challenges in gaining the same level of recognition as her male counterparts. Her uncompromising style, which did not always align with popular tastes, may have also contributed to a more gradual appreciation of her work during her lifetime. She was, however, respected within artistic circles, and her work was acquired by collectors and museums.

In her later years, Bisschop-Robertson reportedly struggled with health issues, including depression and arthritis, which inevitably impacted her ability to work with the same intensity. Despite these difficulties, she continued to create, driven by her deep-seated artistic impulse. She passed away on October 18, 1922, in The Hague.

Legacy and Re-evaluation

For many years after her death, Suze Bisschop-Robertson remained a somewhat overlooked figure in the broader narrative of Dutch art, often overshadowed by the more famous names of the Hague School or the male pioneers of modernism. However, in recent decades, there has been a significant re-evaluation of her work and her contribution. Art historians and curators have increasingly recognized her importance as a forerunner of Dutch expressionism and as a powerful female voice in a period of artistic transition.

Her art stands out for its emotional honesty and its technical audacity. She dared to paint subjects and in a style that challenged conventions, and in doing so, she created a body of work that remains compelling and relevant today. Her focus on the lives of women, rendered with such empathy and strength, offers a valuable counterpoint to the often male-centered narratives of art history.

A major retrospective exhibition in 2022 at Museum Panorama Mesdag in The Hague, marking the centenary of her death, brought her work to a wider audience and solidified her reputation. This exhibition, featuring over seventy pieces, many previously unexhibited, provided a comprehensive overview of her career and highlighted her innovative spirit. It underscored her role not just as a "woman artist" but as a significant artist in her own right, whose work deserves to be considered alongside that of her most esteemed contemporaries. Her influence can be seen in the way she opened doors for other women artists to pursue their own visions with similar courage and conviction.

Conclusion: An Enduring Artistic Voice

Suze Bisschop-Robertson was more than just a participant in the Dutch art scene of her time; she was a distinct and forceful presence. Her bold, expressive paintings, characterized by their robust forms, somber yet rich colors, and profound empathy for her working-class female subjects, mark her as a significant figure in the transition from 19th-century realism to 20th-century modernism in the Netherlands. She navigated the expectations and limitations placed on women artists with tenacity, forging an independent path and creating a body of work that speaks with undiminished power. Her legacy lies in her unflinching artistic vision, her contribution to the diversification of subject matter in Dutch art, and her role as an inspiration for artists who seek to express their truth with authenticity and courage. Today, Suze Bisschop-Robertson is rightfully recognized as a key innovator and a vital voice in the rich tapestry of Dutch art history.