Agostino Brunias, an Italian painter of the eighteenth century, holds a unique and increasingly recognized position in the annals of art history. Born in Rome around 1730, Brunias is primarily celebrated for his vivid depictions of life in the British West Indies, particularly on the islands of Dominica, St. Vincent, Barbados, and St. Kitts. His work offers an invaluable, albeit complex, visual record of colonial society, capturing its diverse inhabitants, social customs, and lush landscapes during a transformative period. While his early career was rooted in the European neoclassical tradition, his West Indian oeuvre stands apart, providing a window into a world rarely depicted with such ethnographic detail by contemporary European artists.

Early Life and Roman Foundations

Agostino Brunias's artistic journey began in Rome, the vibrant heart of the European art world. He is believed to have been born around 1730, though precise details of his early life remain somewhat scarce. He received his formal training at the prestigious Accademia di San Luca, a renowned institution that had nurtured generations of Italian and international artists. It was here that Brunias would have honed his skills in drawing, composition, and the classical principles that underpinned much of European art at the time.

His talent was recognized early, and in 1752, he exhibited an oil painting at the Accademia, signaling his emergence as a professional artist. By 1754, his work had gained further acclaim, winning third prize in the second class of painting at another exhibition. These early successes in Rome provided him with a solid foundation in the prevailing artistic styles, likely encompassing historical, mythological, and decorative painting, which were highly valued. His Roman training would have exposed him to the masterpieces of the Renaissance and Baroque periods, as well as the burgeoning Neoclassicism championed by figures like Anton Raphael Mengs and Johann Joachim Winckelmann, whose ideas were reshaping European aesthetic sensibilities.

A Pivotal Association with Robert Adam

A significant turning point in Brunias's early career came through his association with the influential Scottish architect Robert Adam. Adam, a leading figure in the development of the Neoclassical style in Britain, embarked on a Grand Tour of Italy in the mid-1750s to study classical antiquity firsthand. It was during this period, likely around 1756-1758, that Brunias joined Adam's circle, becoming one of several draughtsmen and artists employed by the architect.

Brunias's role involved assisting Adam in documenting ancient Roman ruins and creating decorative designs for Adam's ambitious architectural projects. He produced colored drawings of classical ruins and decorative schemes, contributing to the rich visual vocabulary that Adam would later deploy in his iconic British country houses. This collaboration was mutually beneficial; Brunias gained exposure to Adam's innovative Neoclassical vision, while Adam benefited from Brunias's skilled draughtsmanship and understanding of decorative painting. Brunias is known to have contributed to the decorative paintings at prominent Adam-designed houses such as Kedleston Hall in Derbyshire and Syon House in Middlesex, creating murals and decorative panels that complemented Adam's elegant interiors. This experience in Britain, working alongside one of its foremost architects, further broadened Brunias's artistic horizons and connected him to a network of influential patrons.

The Journey to the West Indies

In 1764, Brunias's career took an unexpected and defining turn. He was engaged by Sir William Young, 1st Baronet, who had recently been appointed Governor of Dominica, an island newly acquired by Britain from France following the Seven Years' War. Young, an enthusiastic proponent of colonial development, commissioned Brunias to accompany him to the West Indies. The primary purpose of this commission was for Brunias to visually document the islands, their resources, and their inhabitants, likely to promote Young's vision of a prosperous and well-ordered colonial enterprise.

Brunias arrived in the Caribbean around 1765 and spent a significant portion of the next two decades in the region, primarily based in Dominica but also working in St. Vincent, Barbados, St. Kitts, and possibly other islands. This move marked a radical shift in his subject matter, from the classical ruins and aristocratic interiors of Europe to the vibrant, complex, and often fraught realities of colonial life in the tropics. His patron, Sir William Young, and later his son, Sir William Young, 2nd Baronet, continued to be important figures in his career, commissioning numerous works.

Chronicling Colonial Life: Subjects and Themes

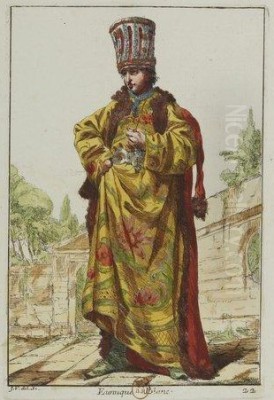

Brunias’s West Indian paintings are characterized by their detailed observation of the diverse populations and social interactions within the colonies. He depicted a wide array of subjects, including market scenes, dances, conversations, domestic activities, and interactions between different social and racial groups. His canvases are populated with European colonists, enslaved Africans, free people of color (often of mixed European and African descent, then referred to by terms like "mulatto," "quadroon," or "octoroon"), and indigenous Carib (Kalinago) people.

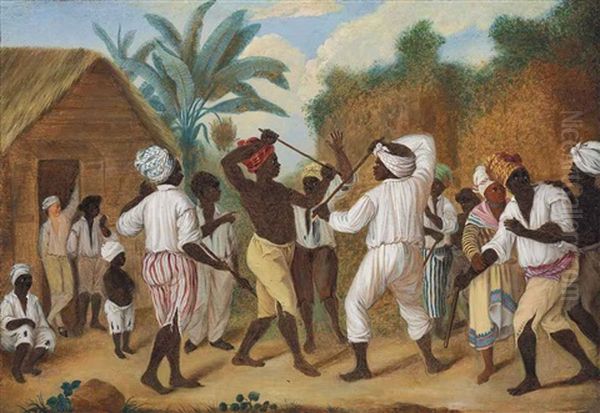

His works often highlight the distinctive dress, adornment, and customs of these groups. For instance, he meticulously rendered the colorful textiles, headscarves (often mandated by sumptuary laws for women of color), and jewelry worn by West Indian women. He also depicted the more formal European attire of the white planter class and the simpler garments of enslaved laborers. Scenes of bustling markets, such as his Linen Market, Dominica or Market Day, Roseau, Dominica, showcase the economic activity and social mingling that characterized these colonial towns. Other paintings capture leisure activities, like the Bélè Dance, Dominica or A Negroes Dance in the Island of Dominica, offering glimpses into the cultural expressions of the Afro-Caribbean population.

Artistic Style: Ethnography and Romanticism

Brunias developed a distinctive style for his West Indian subjects that blended ethnographic observation with a degree of romanticization. His approach has been described as a form of "veritable ethnography," aiming to provide an accurate visual record of the people and their environment. The attention to detail in clothing, physiognomy, and setting suggests a keen observational eye and an intent to document the specificities of West Indian life.

However, his depictions are often imbued with a picturesque or idyllic quality. Figures are typically portrayed with grace and dignity, and scenes of labor are often sanitized or absent, replaced by images of harmonious social interaction or leisurely pursuits. This romanticized lens can be seen as aligning with the pro-planter interests of his patrons, presenting a vision of colonial life that downplayed the brutality of slavery and emphasized social order and contentment. Despite this, the very act of depicting non-European figures with such prominence and detail was unusual for the time and provides invaluable, if filtered, insights. His compositions often recall European genre painting traditions, such as those of Dutch artists like Jan Steen or David Teniers the Younger, but transposed to a Caribbean setting.

Representative Masterpieces

Several of Agostino Brunias's paintings have become iconic representations of eighteenth-century Caribbean life. Among his most celebrated works is the series depicting "Free Women of Color." Paintings such as Free Women of Color with their Children and Servants in a Landscape (c. 1770-1796) are particularly noteworthy. These works portray elegantly dressed women of mixed heritage, often accompanied by their children and enslaved attendants, in lush tropical settings. The paintings highlight the social complexities of the "three-tiered" racial hierarchy prevalent in many West Indian colonies, where free people of color occupied an intermediary status between white Europeans and enslaved Africans. The detailed rendering of their fashionable attire, which often blended European styles with Caribbean adaptations, underscores their social aspirations and relative affluence.

Another significant work is A Cudgelling Match between English and French Negroes in the Island of Dominica (c. 1779). This painting captures a dynamic and somewhat violent scene of stick-fighting, a popular pastime among enslaved and free Black men. It illustrates the cultural practices and rivalries within the Afro-Caribbean community, while also hinting at the underlying tensions of colonial society. View on the River Roseau, Dominica (c. 1770s) showcases Brunias's skill in landscape painting, depicting the island's verdant scenery with local figures engaged in daily activities along the riverbank. His depictions of indigenous Caribs, such as Pacification of the Caribs, St. Vincent, though often reflecting a colonial perspective, are among the few contemporary visual records of these communities.

The Ambiguity of Representation: Patronage and Perspective

The interpretation of Brunias's work is complex and has been the subject of considerable scholarly debate. On one hand, his paintings were undoubtedly shaped by the interests of his patrons, primarily colonial officials and wealthy planters like the Young family. These patrons would have desired images that presented the West Indies as orderly, productive, and even harmonious, thereby justifying colonial rule and the institution of slavery. In this light, the often idealized and picturesque quality of Brunias's scenes can be seen as a form of colonial propaganda, glossing over the harsh realities of plantation labor and the systemic violence of slavery.

On the other hand, Brunias's detailed and often sympathetic portrayal of non-European subjects, particularly free people of color and enslaved Africans, offers a counter-narrative to the more overtly demeaning caricatures common in some contemporary European art. By placing these figures центрально in his compositions and rendering them with individuality and dignity, Brunias provided a visual presence for communities often marginalized or stereotyped. Some scholars argue that his work, perhaps unintentionally, reveals the creolized cultures and complex social negotiations that characterized West Indian societies. His focus on the "mulâtresse" figure, for example, highlights the prevalence of interracial relationships and the emergence of a distinct mixed-heritage population group, a sensitive topic in colonial discourse. The very act of documenting these figures and their lives, even through a romanticized filter, created a body of work that could be, and has been, interpreted in multiple ways, sometimes even co-opted by abolitionist movements who saw in the dignified portrayal of enslaved people an argument for their humanity.

Contemporaries and the Artistic Milieu

Agostino Brunias operated within a broader artistic context that included European artists interested in depicting "exotic" locales and peoples, as well as those focused on more traditional European subjects. His early work with Robert Adam placed him alongside other artists and craftsmen contributing to the Neoclassical movement, such as the Swiss-born painter Angelica Kauffman, who also enjoyed great success in London, and Italian artists like Giovanni Battista Piranesi, whose dramatic etchings of Roman antiquities captivated Europe. The dominant figures in British painting at the time, such as Sir Joshua Reynolds and Thomas Gainsborough, were primarily focused on portraiture and landscape in a grand manner, catering to an aristocratic clientele.

While Brunias was somewhat unique in his sustained focus on the West Indies, other artists did venture to or depict colonial territories. For instance, William Hodges, who accompanied Captain James Cook on his second voyage to the Pacific (1772-1775), produced remarkable landscapes and ethnographic studies of Polynesian and other cultures. John Webber, on Cook's third voyage, similarly documented the peoples and places encountered. Earlier, Dutch artists like Frans Post and Albert Eckhout had depicted colonial Brazil in the 17th century, providing precedents for European artistic engagement with the Americas. In the Caribbean itself, later artists like the Trinidadian Jean Michel Cazabon (19th century) would continue the tradition of depicting local landscapes and life, though with a different sensibility. George Robertson, a British contemporary, also painted West Indian scenes, sometimes with a more overtly picturesque or romantic landscape focus, often commissioned by planters like William Beckford. The engraver Francesco Bartolozzi, highly active in London, was instrumental in popularizing many artists' works, including potentially those derived from Brunias's imagery, through widely circulated prints. Philip Mercier, a French painter active in England, was known for his genre scenes and conversation pieces, a tradition Brunias adapted to the Caribbean context.

Dissemination through Prints and Later Career

A significant aspect of Brunias's impact was the reproduction of his paintings as engravings and aquatints. These prints, often hand-colored, made his images accessible to a much wider audience in Europe and the Americas. Published in sets, such as "Six Views of the Island of Dominica" (1779-80), these prints helped to shape European perceptions of the West Indies. They were popular as decorative items and as sources of information (or misinformation) about colonial life. The prints often carried titles that emphasized the picturesque or ethnographic aspects of the scenes.

Brunias returned to England around 1773 or 1774, exhibiting his West Indian scenes at the Royal Academy and other London venues. He continued to produce paintings based on his Caribbean sketches and experiences. However, he did not achieve the same level of mainstream success or financial stability as some of his London-based contemporaries. Perhaps finding the artistic climate or patronage less favorable than anticipated, or drawn back to the region that had become his primary subject, Brunias eventually returned to the West Indies. He died in Dominica on April 2, 1796, at the approximate age of 66. His will, registered in Dominica, indicates he had established a life there.

Modern Re-evaluation and Scholarly Interest

For a long time, Agostino Brunias was a relatively overlooked figure in mainstream art history, often categorized as a minor colonial painter. However, in recent decades, his work has attracted significant scholarly attention, particularly from historians and art historians specializing in Caribbean studies, colonial art, and the visual culture of slavery and race. Scholars like Mia L. Bagneris, in her book Colouring the Caribbean: Race and the Art of Agostino Brunias, and David Bindman have undertaken in-depth analyses of his oeuvre, exploring its complex relationship with colonial power structures, racial ideologies, and creolized cultural formations.

This renewed interest has led to a more nuanced understanding of Brunias's art. Rather than simply dismissing it as planter propaganda or celebrating it uncritically as ethnographic documentation, contemporary scholarship examines the ambiguities and contradictions within his work. His paintings are now seen as crucial visual documents that, despite their biases, offer rare and detailed glimpses into the social fabric of the eighteenth-century Caribbean. They provide rich material for discussions about identity, representation, and the ways in which art participated in the construction and contestation of colonial narratives. His works are held in important collections, including the Yale Center for British Art, the Brooklyn Museum, Tate Britain, and the Victoria and Albert Museum, ensuring their continued study and appreciation. John E. Crow and Alastair Laing have also contributed significant research, further illuminating the context and interpretation of his West Indian scenes.

Legacy and Conclusion

Agostino Brunias's legacy is multifaceted. As an artist, he created a unique body of work that stands as one of the most extensive visual records of life in the British West Indies during the late eighteenth century. His paintings and the prints derived from them played a role in shaping European perceptions of the Caribbean and its peoples, contributing to a visual archive that continues to inform our understanding of this historical period.

While his work was undeniably influenced by the colonial context in which it was produced, its detailed depictions of diverse social groups, cultural practices, and creolized identities offer invaluable insights that transcend the intentions of his patrons. Brunias captured a world in transition, a society forged from the encounters and collisions of European, African, and indigenous American cultures. His art serves as a compelling, if sometimes problematic, testament to the complexities of colonial life, the resilience of human culture, and the enduring power of images to shape historical memory. Today, his paintings are not just historical documents but are also engaged with critically as art that navigates the intricate terrains of race, power, and representation in the colonial Atlantic world, making Agostino Brunias a figure of enduring relevance.