George Catlin stands as a monumental figure in American art and ethnography. Living from 1796 to 1872, he dedicated a significant portion of his life to an ambitious, self-appointed mission: to visually document the Indigenous peoples of North America, whose cultures he believed were rapidly vanishing under the westward expansion of the United States. Trained initially as a lawyer, Catlin abandoned the legal profession for the allure of art, becoming a painter, explorer, writer, and showman whose work provides an invaluable, albeit complex, window into the lives of Native American tribes in the 19th century. His "Indian Gallery," a vast collection of paintings and artifacts amassed during his travels, along with his extensive writings, cemented his legacy as one of the earliest and most prolific artists to venture into the American West with the explicit goal of cultural preservation through art.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

George Catlin was born in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, on July 26, 1796. His early life was marked by stories of the frontier; notably, his mother, Polly Sutton Catlin, and grandmother were captured by an Iroquois war party during the Wyoming Valley Massacre of 1778, an event that likely instilled in the young Catlin a fascination with Native American life. Following his father's wishes, Catlin pursued a legal education, studying at the Litchfield Law School in Connecticut, one of the most prestigious law schools of its time.

After being admitted to the bar, Catlin practiced law briefly in Lucerne, Pennsylvania, and later Philadelphia, from about 1819 to the early 1820s. However, his heart was not in jurisprudence. He found himself increasingly drawn to art, spending his spare time sketching courtroom figures and local scenes. He was largely self-taught as an artist, initially focusing on miniature painting before transitioning to portraiture. His passion for art eventually overwhelmed his legal ambitions. He famously traded his law books for brushes and palettes, resolving to pursue painting full-time.

A pivotal moment occurred around 1824 or 1826 (accounts vary slightly) when Catlin witnessed a delegation of Native American leaders from various western tribes visiting Philadelphia. Struck by their dignity, appearance, and what he perceived as the nobility of their "untouched" state, Catlin experienced an epiphany. He felt a profound calling to dedicate his artistic talents to recording the appearances and customs of these peoples before they were irrevocably altered or destroyed by encroaching American civilization. This encounter solidified his life's mission.

The Great Western Expeditions

Fueled by his newfound purpose, George Catlin embarked on a series of arduous journeys into the American West between 1830 and 1836. These expeditions were unprecedented in their scope and ambition for an artist of his time. He sought to create a comprehensive visual record of as many tribes as possible, venturing far beyond the established frontiers into territories largely unknown to most white Americans.

His first major trip, in 1830, took him to St. Louis, then a gateway to the West. There, he met General William Clark, of Lewis and Clark fame, who was serving as Superintendent of Indian Affairs. Clark granted Catlin permission and assistance, facilitating his travels among various tribes relocated near St. Louis and along the lower Missouri River, including the Sauk, Meskwaki (Fox), Iowa, and Missouri peoples.

The most significant of these journeys occurred in 1832 when Catlin traveled nearly 2,000 miles up the Missouri River aboard the steamboat Yellow Stone. This voyage took him deep into the heart of the Great Plains, reaching Fort Union near the present-day border of North Dakota and Montana. During this trip, he spent several weeks among the Mandan people, whose villages became a central focus of his work. He also encountered and painted members of the Crow, Blackfoot, Assiniboine, Hidatsa, and Arikara tribes.

Subsequent expeditions between 1834 and 1836 saw Catlin travel extensively through the southern Plains and the Great Lakes region. He journeyed overland with the U.S. Dragoons into Comanche and Kiowa territory (present-day Oklahoma and Texas) in 1834. He later traveled among the tribes of the upper Mississippi River and the Great Lakes, including the Ojibwe (Chippewa), Menominee, Winnebago (Ho-Chunk), and Sioux (Lakota/Dakota).

Throughout these five major trips, Catlin worked tirelessly and rapidly, often under challenging conditions. He aimed to capture not just individual likenesses but also the broader cultural context – ceremonies, dances, hunting scenes, village life, and landscapes. He painted hundreds of portraits and scenes directly from life, usually in oil on canvas or board, prioritizing immediacy and accuracy over polished academic finish. He also meticulously collected artifacts, including clothing, weapons, tools, pipes, and even lodges, to supplement his visual record.

The Indian Gallery: A Vision Shared

Upon returning from his western travels, Catlin faced the challenge of how to share his monumental collection and advocate for the Native American cultures he had documented. His solution was the creation of "Catlin's Indian Gallery," a unique combination of art exhibition and ethnographic museum. He envisioned it not just as a display of paintings but as an immersive experience that could educate the American public and garner support for the preservation of Native cultures, or at least their memory.

The Gallery initially comprised over 500 paintings – portraits, landscapes, and scenes of daily life and ritual – alongside the extensive collection of artifacts he had gathered. He first exhibited parts of the collection in cities like Pittsburgh and Cincinnati in the mid-1830s. The full Gallery debuted to great acclaim in New York City in 1837. Catlin arranged the paintings salon-style, often floor-to-ceiling, creating a powerful visual impact. He accompanied the exhibition with lectures, drawing on his firsthand experiences to explain the artworks and the customs they depicted.

Seeking a wider audience and hoping for government patronage, Catlin took his Indian Gallery to Washington D.C., lobbying Congress unsuccessfully to purchase the collection for the nation. Disappointed by the lack of official support in the United States, he sailed for Europe in 1839. The Indian Gallery opened in London in 1840 at the Egyptian Hall in Piccadilly, where it became a sensation. It attracted large crowds, including royalty (Queen Victoria visited), scientists, and fellow artists.

To enhance the Gallery's appeal and authenticity, Catlin later incorporated live performances. He arranged for groups of Native Americans, first Ojibwe and later Iowa, to travel to Europe and appear alongside the exhibition, demonstrating dances, songs, and rituals. While popular with audiences, this practice drew criticism and raised ethical concerns about the exploitation of the performers, some of whom tragically died while abroad. The shows, however, undoubtedly increased the Gallery's fame and Catlin's notoriety.

After several successful years in London, Catlin moved the Gallery to Paris in 1845. It was again met with enthusiasm, visited by King Louis-Philippe I and praised by intellectuals and artists, including the influential critic Charles Baudelaire. Despite its popularity, the Gallery was a massive undertaking and proved financially unsustainable. Mounting debts eventually forced Catlin into bankruptcy.

Artistic Style and Technique

George Catlin's artistic style is best characterized as documentary realism, driven by his ethnographic goals rather than purely aesthetic concerns. As a largely self-taught artist, his technique sometimes lacked the polish and academic rigor of his contemporaries. Critics then and now have pointed to occasional weaknesses in anatomy, perspective, and compositional complexity. However, these perceived shortcomings are often outweighed by the immediacy, vitality, and sheer informational value of his work.

Catlin typically painted quickly, often completing portraits in a single sitting and capturing scenes with rapid brushstrokes. This speed was necessary given the constraints of his travels and the need to record as much as possible. His primary medium was oil paint, usually applied to canvas or sturdy paperboard panels that were relatively portable. His color palette, while sometimes criticized as harsh or unsophisticated, effectively conveyed the vibrant clothing, beadwork, and landscapes he encountered.

His portraits aimed to capture individual likenesses and convey the dignity and character of his sitters. He often depicted them in traditional attire, sometimes holding significant objects or weapons, against simple, neutral backgrounds that focused attention on the subject. While adhering to a realistic approach, his depictions often carried an undercurrent of romanticism, reflecting his admiration for his subjects and his belief in the "noble savage" archetype prevalent in the era.

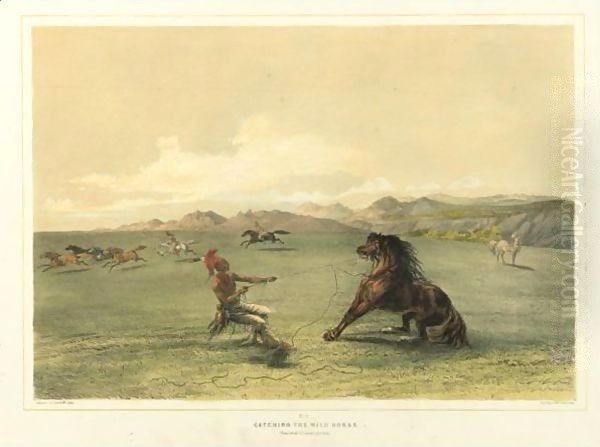

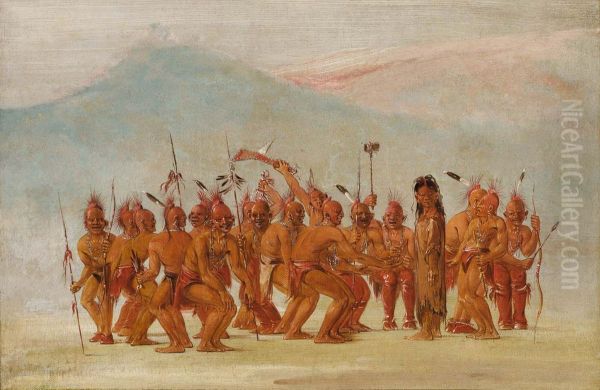

His scenes of Native life – buffalo hunts, dances, village activities, and ceremonies like the Mandan O-kee-pa – are dynamic and filled with detail. They provide invaluable visual information about social structures, cultural practices, and the relationship between Plains peoples and their environment, particularly the bison. While sometimes sacrificing precise anatomical accuracy for energy and narrative clarity, these works effectively communicate the drama and significance of the events depicted. Compared to the more technically refined and detailed work of artists like Karl Bodmer, who traveled the Missouri River shortly after Catlin, Catlin's paintings possess a raw energy and a sense of direct, personal encounter.

Key Subjects and Themes

Catlin's work revolved around a core set of subjects and themes central to his mission of documenting Native American life, particularly on the Great Plains. His primary focus was on the people themselves. He painted hundreds of portraits, seeking to capture the likenesses of chiefs, warriors, women, and children from numerous tribes, including the Mandan, Sioux, Crow, Blackfoot, Pawnee, Comanche, Kiowa, Ojibwe, and many others. These portraits emphasized individual identity and cultural markers like hairstyles, face paint, and adornments.

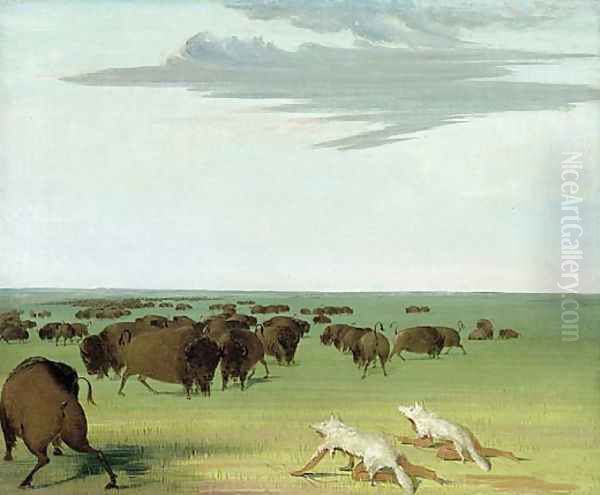

The American bison, or buffalo, was another crucial subject. Catlin recognized the centrality of the buffalo to the Plains cultures – as a source of food, shelter, clothing, and spiritual power. He painted numerous dramatic scenes of buffalo hunts, showcasing various hunting techniques on foot and horseback. These paintings conveyed the excitement and danger of the hunt, as well as the deep connection between the hunters and their prey. He also painted landscapes featuring vast herds of buffalo, underscoring their abundance at the time and implicitly warning of their potential demise.

Ceremonies and rituals formed a significant part of his documentation. His most famous, and controversial, depictions were of the Mandan O-kee-pa ceremony, a complex multi-day ritual involving painful physical ordeals intended to ensure community well-being and the return of the buffalo. Catlin was one of the few outsiders to witness and record this ceremony before the Mandan were decimated by smallpox in 1837. His detailed paintings and written accounts, while questioned by some contemporaries, remain vital sources of information about Mandan religious life. He also painted numerous other dances, social gatherings, and games.

Daily life and material culture were consistently documented. Catlin painted scenes of village life, showing lodges (tipis, earth lodges), domestic activities, and social interactions. He paid close attention to clothing, weaponry, tools, and decorative arts, often depicting these items with considerable detail in both his portraits and genre scenes. His landscapes, while perhaps less artistically developed than his figurative work, served to place the people within their specific environments, depicting the prairies, rivers, and distinctive geological formations of the West.

Underlying all these subjects was Catlin's pervasive theme of the "vanishing race." He genuinely believed he was racing against time to record cultures doomed to extinction by disease, warfare, and assimilation. This sense of urgency permeates his work and writings, lending them a poignant, elegiac quality. While this perspective is now viewed critically for its deterministic and often paternalistic assumptions, it was the driving force behind his extraordinary efforts.

Representative Works

George Catlin's vast output includes many iconic images that have become synonymous with 19th-century depictions of Native Americans. Among his most celebrated works are:

_Máh-to-tóh-pa (Four Bears), Mandan Chief_ (1832): Perhaps Catlin's most famous portrait, depicting the respected Mandan leader in full ceremonial regalia, including an elaborate eagle-feather headdress and a painted robe depicting his war exploits. Catlin admired Mah-to-toh-pa greatly and painted several portraits of him. This image captures the chief's dignity and status.

_Stu-mick-o-súcks (Buffalo Bull's Back Fat), Head Chief, Blood Tribe_ (1832): A striking portrait of a prominent Blackfoot leader, known for his imposing presence and elaborate attire. The painting highlights the intricate details of his clothing, face paint, and bear claw necklace, conveying power and authority.

_Pigeon's Egg Head (Wi-jún-jon) Going to and Returning from Washington_ (1837-1839): A unique diptych showing the Assiniboine leader Wi-jún-jon in two contrasting states. On one side, he is depicted in traditional attire before visiting Washington D.C.; on the other, he is shown upon his return, awkwardly clad in ill-fitting Euro-American military finery. Catlin used this work to comment critically on the often-detrimental effects of government assimilation policies.

_Buffalo Hunt under the Wolf-Skin Mask_ (1832-1833): One of many dynamic buffalo hunting scenes, this painting illustrates a specific technique where hunters disguised themselves under wolf skins to approach the herd closely. It showcases Catlin's ability to capture action and narrative detail.

_The Last Race, Part of the O-kee-pa Ceremony_ (1832): A dramatic and somewhat harrowing depiction of one element of the Mandan O-kee-pa ritual, involving participants enduring physical torture. This work exemplifies Catlin's commitment to recording even the most challenging aspects of the cultures he encountered.

_Falls of St. Anthony, Upper Mississippi_ (c. 1835): Representative of Catlin's landscape work, this painting depicts the significant waterfall on the Mississippi River (near present-day Minneapolis) before extensive industrial development. It captures a sense of the wild, untamed nature of the West that Catlin sought to preserve visually.

_Bird's-Eye View of the Mandan Village_ (1837-1839): A detailed overview of the Mandan settlement of Mih-Tutta-Hangkusch, showing the layout of their distinctive circular earth lodges clustered near the Missouri River. This painting provides valuable architectural and sociological information.

These examples represent only a fraction of the hundreds of works comprising the original Indian Gallery, each contributing to Catlin's comprehensive visual encyclopedia of Native American life in the 1830s.

Writings and Publications

Beyond his prolific output as a painter, George Catlin was also a dedicated writer. He understood the importance of supplementing his visual record with written descriptions, narratives, and reflections based on his firsthand experiences. His writings provide invaluable context for his paintings and offer further insights into his observations and perspectives.

His most significant literary work is _Letters and Notes on the Manners, Customs, and Condition of the North American Indians_. First published in London in 1841 in two volumes, this book compiled letters and notes written during his travels between 1832 and 1839. Lavishly illustrated with outline engravings based on his paintings, it offered detailed accounts of the tribes he visited, describing their social structures, beliefs, ceremonies, hunting practices, and daily lives. Written in an engaging, accessible style, it became immensely popular and remains a foundational text in American ethnography, despite reflecting some of the biases of its time.

In 1844, Catlin published _Catlin's North American Indian Portfolio_, a collection of large, high-quality hand-colored lithographs reproducing some of his most dramatic paintings, particularly hunting scenes and amusements. Aimed at a wealthier audience, this portfolio further disseminated his images and cemented his reputation. Several editions followed, making it one of the most influential visual publications on Native Americans in the 19th century.

Later in life, Catlin continued to write about his experiences and advocate for Native peoples. _Catlin's Notes of Eight Years' Travels and Residence in Europe with his North American Indian Collection_ (1848) chronicled his time exhibiting the Indian Gallery abroad. After travels in South and Central America in the 1850s, he published _Life Amongst the Indians: A Book for Youth_ (1861) and _Last Rambles Amongst the Indians of the Rocky Mountains and the Andes_ (1867). These later works, while less focused than his initial magnum opus, continued to blend adventure narrative with ethnographic observation.

Catlin's writings, like his paintings, were driven by his sense of mission. He used his publications to educate the public, argue for the humanity and dignity of Native Americans, and lament the destructive impact of westward expansion. While his perspective was shaped by 19th-century notions like the "vanishing race," his detailed observations and passionate advocacy make his books enduringly important historical documents.

European Travels and Reception

Catlin's decision to take his Indian Gallery to Europe in 1839 marked a significant chapter in his career. Frustrated by the lack of government support in the U.S., he hoped for greater appreciation and potential buyers abroad. His exhibitions in London (1840-1844) and Paris (1845-1848) were indeed major events, generating considerable public interest and commentary.

In London, the Egyptian Hall exhibition was a novelty. Catlin's combination of hundreds of paintings, artifacts, lectures, and eventually live Native American performers created a spectacle that drew large crowds. The British press covered the Gallery extensively, and it attracted visitors from all levels of society, including scientists, writers, and artists. The presence of the Ojibwe and later the Iowa delegations added an element of perceived authenticity that fascinated audiences, though it also led to logistical challenges and ethical debates.

The Paris exhibition at the Salle de Valentino was similarly successful, attracting the attention of the French intellectual and artistic elite. King Louis-Philippe I visited multiple times and commissioned several copies of Catlin's paintings. Perhaps the most notable commentary came from the poet and art critic Charles Baudelaire, who reviewed the exhibition in 1846. Baudelaire praised Catlin's ability to capture the "proud, free character and noble expression" of his subjects, admiring the energy and directness of his style. Some art historians suggest Catlin's work may have influenced French artists like Eugène Delacroix, who shared an interest in exotic subjects and vibrant color.

Despite the popular and critical acclaim, the European venture ultimately proved financially disastrous for Catlin. The costs of transporting and maintaining the vast collection, renting large venues, and supporting the visiting Native American groups were enormous. Catlin fell deeply into debt, leading to his bankruptcy and the temporary seizure of his collection by creditors in 1852. While the European tour significantly raised Catlin's international profile and disseminated knowledge about Native Americans, it failed to secure the long-term financial stability he sought for himself and his collection.

Later Life and Financial Struggles

The years following the financial collapse of his European venture were difficult for George Catlin. He managed to salvage his original Indian Gallery from creditors with the help of Joseph Harrison Jr., a wealthy American industrialist who paid off Catlin's debts and stored the collection in Philadelphia. However, Catlin himself remained financially precarious.

Driven by a continued desire to explore and document Indigenous cultures, Catlin embarked on new travels in the 1850s, this time to South and Central America. He visited tribes in regions like the Amazon basin and the Andes, painting portraits and scenes in a manner similar to his North American work. He believed some of these groups represented earlier stages of cultural development or possible origins of North American peoples.

During this period and after returning to Brussels, where he lived for a time, Catlin created a second major collection of paintings. Known as the "Cartoon Collection," it consisted of hundreds of copies and reworkings of his original North American Indian paintings, often executed on paper or cardboard in a simplified, linear style (hence the term "cartoon," referring to preparatory drawings). He created this collection partly from memory and partly from earlier sketches, hoping it might still find a buyer, perhaps the U.S. government.

Catlin continued to write and publish, trying to capitalize on his earlier fame, but financial success remained elusive. He returned to the United States in 1870, old and nearly deaf. He spent his final years living modestly, first in Washington D.C., where he worked on his paintings in a studio provided at the Smithsonian Institution, still hoping for government acquisition. He later moved to Jersey City, New Jersey.

George Catlin died in Jersey City on December 23, 1872, at the age of 76. He passed away in relative obscurity, his great ambition of having the nation acquire his life's work unrealized during his lifetime. His original Indian Gallery remained in storage in Philadelphia.

Contemporaries and Context

George Catlin worked during a period of intense national expansion and burgeoning American identity, alongside a diverse group of artists, writers, and explorers who were also engaging with the American landscape and its inhabitants. Understanding his contemporaries helps place his unique contributions in context.

Among artists focusing on Native American subjects, Catlin had several important contemporaries, often viewed as rivals or counterparts. Karl Bodmer (1809-1893), a Swiss artist, traveled up the Missouri River just a year after Catlin, accompanying the German naturalist Prince Maximilian zu Wied. Bodmer's meticulously detailed and technically sophisticated watercolors and engravings offer a different, often considered more scientifically precise, view of the same tribes Catlin painted. Alfred Jacob Miller (1810-1874) traveled west to the Rocky Mountains in 1837 with the Scottish nobleman Sir William Drummond Stewart, creating romanticized watercolor sketches of mountain men, Native Americans (particularly Shoshone), and dramatic landscapes.

Seth Eastman (1808-1875), a U.S. Army officer and trained artist, created detailed depictions of Sioux and Ojibwe life based on his postings at Fort Snelling in Minnesota. His work, often illustrating Henry Rowe Schoolcraft's government-sponsored studies, provides another valuable visual record. John Mix Stanley (1814-1872) also assembled a large "Indian Gallery" based on his western travels, but tragically, most of it was destroyed in a fire at the Smithsonian in 1865. In Canada, Paul Kane (1810-1871) undertook extensive travels across the continent, documenting Indigenous peoples of the Great Lakes, Canadian Prairies, and Pacific Northwest, influenced partly by Catlin's example.

Catlin also interacted with figures outside the art world. His relationship with William Clark (1770-1838) was crucial for accessing tribes along the Missouri. He operated within a broader cultural context shaped by writers like James Fenimore Cooper, whose novels popularized romantic notions of Native Americans, and explorers documenting the West. His work can be contrasted with the dominant landscape painters of the era, the Hudson River School artists like Thomas Cole (1801-1848) and Asher B. Durand (1796-1886), who focused primarily on the sublime beauty of the eastern American wilderness, though later artists like Albert Bierstadt would bring a similar romantic sensibility to western landscapes.

In the realm of natural history documentation, Catlin's comprehensive approach parallels the work of John James Audubon (1785-1851), who was concurrently undertaking his monumental project to paint all the birds of North America. Both men shared a passion for documenting the natural world and its inhabitants, combining artistic skill with scientific observation and extensive travel. Earlier artists like Charles Bird King (1785-1862) had painted portraits of Native American delegates visiting Washington D.C., but Catlin was among the first to travel extensively to their homelands for systematic documentation. His European exhibitions brought him into contact with figures like Charles Baudelaire (1821-1867) and potentially influenced artists like Eugène Delacroix (1798-1863).

Legacy and Historical Significance

George Catlin's legacy is immense and multifaceted. Despite the financial hardships and lack of official recognition during his lifetime, his work has endured as an unparalleled resource for understanding Native American cultures of the Great Plains in the 1830s. His primary achievement lies in the sheer volume and scope of his documentation – the hundreds of paintings and extensive writings produced during a period of profound cultural transition.

The ethnographic value of his work is undeniable. He captured the likenesses, attire, customs, and environments of dozens of tribes, many of whose traditional ways of life were drastically altered or destroyed shortly after his visits (most notably the Mandan). His paintings and notes provide crucial information for anthropologists, historians, and tribal members seeking to reconnect with their heritage. The Catlin collections at the Smithsonian American Art Museum constitute one of the most important archives of Native American visual history.

Catlin was a pioneer in using art explicitly for cultural preservation and advocacy. He passionately argued for the value and dignity of Native cultures at a time when prevailing attitudes were often dismissive or hostile. His "Indian Gallery" was an innovative concept, aiming to educate a broad public and foster empathy. While his perspective was colored by the romantic "vanishing race" trope, his efforts fundamentally shaped subsequent perceptions and artistic representations of Native Americans.

His influence extended to other artists who followed him west, establishing a tradition of western American art focused on Indigenous subjects and landscapes. His writings became foundational texts, widely read in the 19th century and still consulted today.

Posthumously, Catlin's vision for national recognition was partially realized. In 1879, seven years after his death, the widow of Joseph Harrison Jr. donated the original Indian Gallery – over 500 paintings – to the U.S. National Museum (now the Smithsonian Institution). Later, the "Cartoon Collection" also entered the Smithsonian's holdings through the generosity of collector Paul Mellon. Today, the Smithsonian American Art Museum holds the definitive collection of Catlin's work, frequently exhibiting it and making it accessible for study. His contributions are also commemorated; for instance, a sculpture titled "The Welcoming" stands near his burial site in Green-Wood Cemetery, Brooklyn, honoring his role as an early chronicler of the West.

While contemporary scholarship critically examines Catlin's romanticism, his role in promoting stereotypes, and the ethical complexities of his exhibitions, his status as a key figure in American art and ethnography remains secure. He undertook an extraordinary, self-driven mission with remarkable dedication, leaving behind a rich and complex legacy that continues to provoke discussion and provide invaluable insight into a pivotal era of American history.

Conclusion

George Catlin was more than just a painter; he was an ethnographer, an adventurer, a writer, and a showman driven by an urgent sense of purpose. His life's work, the creation of a vast visual and written record of Native American cultures, stands as a testament to his dedication and ambition. While navigating the complexities of 19th-century attitudes and facing persistent financial struggles, he produced an unparalleled archive that captured the dignity, diversity, and dynamism of Indigenous life on the brink of profound change. His paintings, particularly those in the Indian Gallery, along with his detailed writings, remain essential resources for understanding American history and Native American heritage. George Catlin's legacy endures in the galleries of the Smithsonian and in the ongoing study of the peoples and cultures he devoted his life to documenting.