Charles Frederick Goldie stands as one of New Zealand's most renowned, and simultaneously, most debated, Pākehā (New Zealander of European descent) artists. His legacy is inextricably linked to his meticulously detailed portraits of Māori kaumātua (elders) and rangatira (chiefs) from the late 19th and early 20th centuries. While lauded for his technical skill and for preserving the likenesses of significant Māori figures, Goldie's work has also faced scrutiny for its romanticized and often melancholic portrayal of a people perceived by many colonial observers as a "dying race." This exploration delves into the life, art, controversies, and enduring impact of Charles Frederick Goldie, an artist whose canvases continue to evoke powerful responses and discussions about identity, representation, and colonial history in Aotearoa New Zealand.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Charles Frederick Goldie was born in Auckland on October 20, 1870, into a prominent and relatively affluent family. His father, David Goldie, was a successful timber merchant and a notable public figure, serving as Mayor of Auckland and a Member of Parliament. His mother, Maria Partington Goldie (née Paterson), was an amateur artist herself and is credited with fostering young Charles's burgeoning interest in art. This supportive environment provided him with opportunities that were not available to many aspiring artists in colonial New Zealand.

Goldie received his initial education in Auckland. His artistic talents were evident from an early age, and he began formal art training locally. He won prizes from the Auckland Society of Arts and the New Zealand Art Students' Association, showcasing his early promise. His still life paintings, for instance, were first exhibited in 1886 at the New Zealand Art Students' Association exhibition, indicating his early engagement with the formal art world. Recognizing the need for more advanced instruction to hone his skills, Goldie, with family support, made the pivotal decision to travel to Europe.

Parisian Training: The Académie Julian

In 1892, at the age of 22, Charles Goldie embarked for Paris, the undisputed center of the art world at the time. He enrolled at the prestigious Académie Julian, a private art school that attracted students from across the globe, including many Americans and other international artists seeking an alternative to the more rigid École des Beaux-Arts. The Académie Julian was known for its roster of distinguished Salon artists as instructors.

During his time in Paris, which extended until 1898, Goldie studied under several eminent figures of the French academic tradition. These included William-Adolphe Bouguereau, a master of idealized figurative painting and a dominant force in the Salon; Gabriel Ferrier; Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant, known for his Orientalist scenes and portraits; and Lucien Doucet. Some sources also mention Tony Robert-Fleury and Jean-Paul Laurens as influential figures at the Académie. This training instilled in Goldie a profound respect for meticulous draughtsmanship, anatomical accuracy, and a polished, highly finished surface – hallmarks of the academic style. He diligently studied anatomy, which would prove invaluable for his later portraiture, and also developed a keen interest in art history. His dedication was recognized with a gold medal at the Académie Julian, a testament to his skill and application.

Return to New Zealand and the Focus on Māori Portraiture

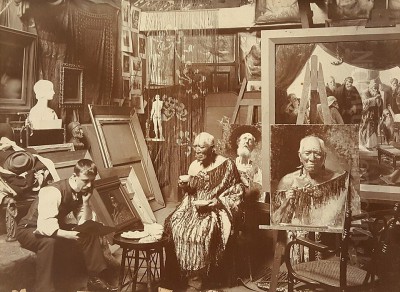

Upon his return to Auckland in 1898, Goldie was equipped with a sophisticated European academic technique. He briefly established a teaching studio and also collaborated with another Auckland artist, Louis John Steele, who had also studied in Paris. Steele had returned to New Zealand earlier and had already begun painting Māori subjects. Together, they worked on a large-scale historical painting, "The Arrival of the Māoris in New Zealand" (1898), depicting a romanticized and dramatic scene of the first canoes reaching Aotearoa. This collaboration, however, was short-lived, and Goldie soon moved away from grand historical narratives.

Instead, Goldie found his true calling in the portraiture of Māori individuals. This decision was significant. By the turn of the century, there was a prevailing Pākehā sentiment that Māori, as a distinct race and culture, were in decline due to disease, land loss, and the pressures of colonization. Artists like Goldie, and his slightly older contemporary Gottfried Lindauer (a Bohemian-born artist who had arrived in New Zealand in 1874), saw themselves as chroniclers, preserving the likenesses of what they and many others believed to be the last generation of "pure-blooded" Māori, particularly those who bore the traditional tā moko (facial and body tattoos).

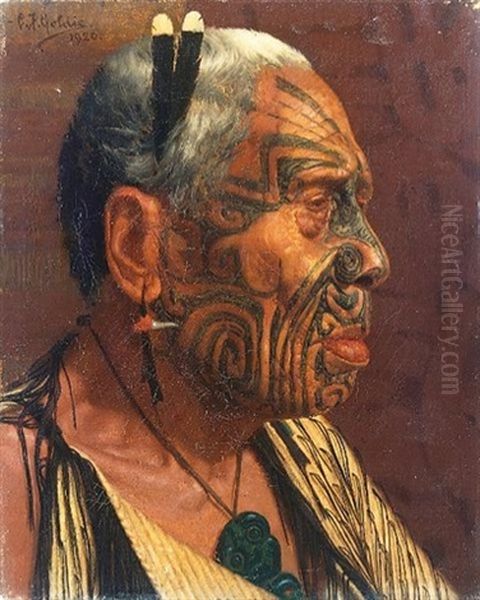

Goldie established a studio in Auckland and began to seek out elderly Māori, often rangatira or individuals of high standing, to sit for him. He would sometimes pay his sitters, provide them with accommodation, and engage with them, though the depth and nature of these interactions remain a subject of discussion. His portraits were characterized by an almost photographic realism, a direct legacy of his Parisian training. He meticulously rendered the intricate patterns of moko, the textures of skin weathered by age and sun, the sheen of hair, and the details of traditional garments like korowai (cloaks) and adornments such as heitiki (greenstone pendants) and huia feathers.

Artistic Style and Technique

Goldie's artistic style was firmly rooted in the 19th-century European academic tradition. His primary goal was verisimilitude – the faithful representation of his subjects. He worked predominantly in oils, applying paint in smooth, carefully blended layers to achieve a highly polished finish that minimized visible brushstrokes. This technique, favored by academic painters like Bouguereau and Jean-Léon Gérôme, aimed for an illusion of reality.

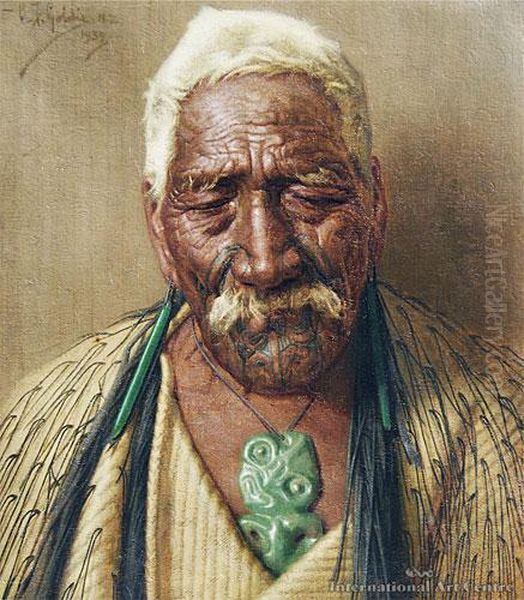

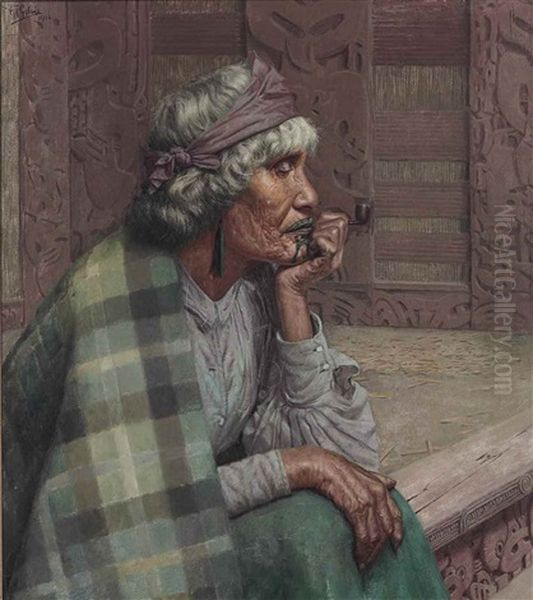

He paid extraordinary attention to detail. The rendering of tā moko was particularly crucial, as these were not mere decorations but profound cultural markers conveying genealogy, tribal affiliation, and social status. Goldie's accuracy in depicting these intricate designs is one reason his works are valued by Māori descendants today as records of their ancestors. He was equally meticulous in capturing the nuances of aging skin – wrinkles, folds, and variations in pigmentation. The eyes of his subjects often convey a sense of weariness, contemplation, or melancholy, contributing to the pathos that many viewers find in his work.

Goldie often used fine-grain canvas or, occasionally, specially prepared teak panels, which provided a smooth surface conducive to his detailed approach. He would sometimes use photographs as aides-mémoires, a common practice among realist painters of the era, though he always worked from life models for the core of his portraits. His compositions were generally conventional, focusing on the head and shoulders or a three-quarter view, allowing the sitter's face and adornments to be the central focus. The backgrounds were typically dark and subdued, further emphasizing the subject. This approach contrasted with some of Lindauer's portraits, which occasionally featured more elaborate settings or narrative elements.

Key Themes and Subjects: The "Noble Relic"

The overarching theme in Goldie's Māori portraiture is often interpreted through the colonial lens of the "dying race" theory. His subjects were almost exclusively elderly Māori, individuals who had lived through a period of immense upheaval and cultural loss. Their expressions, as captured by Goldie, frequently evoke a sense of sorrow, resignation, or a dignified but fading grandeur. Titles of his paintings often reinforced this notion, such as "The Last of the Cannibals (Tumai Tawhiti)" or "A Noble Relic of a Noble Race."

This portrayal, while perhaps intended by Goldie as a sympathetic tribute, has been criticized by later art historians and cultural commentators. Critics argue that by focusing on the aged and the seemingly moribund, Goldie inadvertently or intentionally perpetuated the colonial myth of Māori decline, overlooking the resilience, adaptation, and ongoing vitality of Māori culture. His work rarely depicted younger Māori or engaged with the contemporary realities of Māori life and their struggles for self-determination in the early 20th century.

Despite these criticisms, many Māori descendants today view Goldie's portraits of their tūpuna (ancestors) as taonga (treasures). The paintings serve as precious visual links to their heritage, preserving the likenesses of individuals whose images might otherwise have been lost. The emotional connection many Māori feel towards these portraits transcends the art historical debates about Goldie's motivations or the colonial context of their creation. For them, these are not just paintings; they are representations of revered ancestors.

Representative Works

Goldie was a prolific painter, and many of his works are iconic in New Zealand art history. Some notable examples include:

"The Arrival of the Māoris in New Zealand" (1898, with Louis J. Steele): A large, dramatic historical painting, quite different from his later portraiture, showcasing his academic training in figure composition and narrative.

"Darby and Joan (A Chieftain of the Arawa Tribe and his Wife)" (1903) / "Memories, Ena Te Papatahi, an Arawa Chieftainess": This portrait of Ena Te Papatahi is one of his most famous. She sat for him multiple times, and he depicted her with great sensitivity, capturing her moko kauae (chin tattoo) and dignified presence.

"A Good Joke (Ina Te Papatahi, an Arawa Chieftainess)" (1905): Another portrait of Ena Te Papatahi, this time capturing a moment of amusement, which is somewhat rarer in his oeuvre that often tends towards solemnity.

"The Last of the Cannibals (Tumai Tawhiti)" (1908) / "Memories, The Last of his Tribe (Tumai Tawhiti)": The title itself is provocative and reflects the colonial attitudes of the time. The portrait depicts an elderly man with a deeply lined face and a melancholic expression.

"Patara Te Tuhi" (various portraits, e.g., 1913): Patara Te Tuhi, a Ngāti Mahuta chief and secretary to the Māori King, was another frequent sitter. Goldie captured his thoughtful and intelligent demeanor.

"Te Aho o Te Rangi Wharepu, A Noted Ngati Mahuta Warrior" (1906): A powerful portrait showcasing the warrior's moko and adornments.

"Wiremu Tamihana Tarapipipi Te Waharoa": Goldie painted historical figures as well, sometimes based on earlier photographs or sketches, though his primary focus was on living sitters.

"Forty Winks" (1900): Depicting an elderly Māori man dozing, a study in peaceful repose.

"Reverie (Ina Te Papatahi)" (1916) / "A Noble Relic of a Noble Race": Again featuring Ena Te Papatahi, this work, with its alternative title, explicitly frames the subject within the "noble savage" and "dying race" tropes.

These works, and many others, are held in public galleries and private collections throughout New Zealand and internationally. They are characterized by their technical polish and the intense psychological presence of the sitters.

Collaboration, Contemporaries, and Artistic Context

Goldie's artistic world was shaped by his training and the art scene of his time. His early collaboration with Louis John Steele on "The Arrival of the Māoris in New Zealand" was significant, though their paths diverged. Steele, like Goldie, had Parisian training and also painted Māori subjects, but his output was less focused and his legacy less prominent than Goldie's.

The most important contemporary for Goldie in terms of Māori portraiture was Gottfried Lindauer (1839-1926). Lindauer, a Czech artist, arrived in New Zealand in 1874 and had already established a reputation for his Māori portraits by the time Goldie returned from Paris. Lindauer's style was also realistic, but perhaps somewhat softer and less intensely psychological than Goldie's. He often worked on commission for patrons like Henry Partridge, who amassed a large collection of his works. There was an element of rivalry, and comparisons are often drawn between the two artists. Some critics of the time, and later, considered Goldie's work more technically refined due to his rigorous Parisian academic training, while others found Lindauer's portrayals more sympathetic or less overtly melancholic.

In the broader New Zealand art scene, Goldie was a traditionalist. Artists like Petrus Van der Velden, a Dutch immigrant, brought a darker, more expressive European Romanticism to New Zealand landscape and genre painting. The rise of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism in Europe had a delayed impact in New Zealand, but artists like James Nairn, Frances Hodgkins, Margaret Stoddart, and Dorothy Kate Richmond were beginning to explore more modern approaches. Hodgkins, in particular, would go on to become New Zealand's most celebrated expatriate modernist painter, her style evolving far from the academic realism Goldie championed. Goldie, however, remained steadfast in his academic approach, famously dismissing modernist movements like Cubism and Impressionism as "incompetent camouflage" in a defense of his art published in the Auckland Star in 1934.

His teachers in Paris, such as William-Adolphe Bouguereau and Benjamin-Constant, were giants of the French Salon, but their style was already being challenged by avant-garde movements. Other academic painters whose work shares a similar meticulousness, if not subject matter, include Jean-Léon Gérôme and Lawrence Alma-Tadema. Goldie's commitment to this tradition placed him increasingly at odds with the direction art was taking in the 20th century.

Critical Reception, Controversy, and Awards

Goldie's work enjoyed considerable popularity and critical acclaim during his lifetime, particularly in the early decades of the 20th century. His paintings were sought after by collectors and institutions. He exhibited regularly and received numerous accolades. In 1934, he was awarded the King George V Silver Jubilee Medal. In 1935, he was appointed an Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE) for his services to art. His work was also exhibited internationally, including at the Royal Academy in London and the Paris Salon, where he received an honorable mention in 1900.

However, his conservative style and thematic focus also drew criticism. As modernist ideas gained traction, Goldie's academic realism was increasingly seen as old-fashioned and out of step with contemporary artistic developments. Some critics dismissed his work as mere photographic representation, lacking artistic invention or emotional depth beyond a sentimentalized pathos. The term "second-rate Lindauer" was sometimes used by detractors.

The most significant and enduring controversy surrounds the colonial context of his work and the representation of Māori. As discussed, the "dying race" narrative implicit in many of his paintings has been a focal point for post-colonial critique. Art historians like Leonard Bell and Ngahuia Te Awekotuku have explored the complexities of Goldie's oeuvre, acknowledging his technical skill while also analyzing the power dynamics inherent in a Pākehā artist depicting Māori subjects within a colonial framework. The debate continues: was Goldie a sympathetic chronicler preserving a vanishing culture, or did his work reinforce colonial stereotypes and contribute to the objectification of Māori?

Later Life, Health, and Declining Output

Goldie's artistic output began to decline in the 1920s, partly due to his own health problems and perhaps also due to the changing artistic climate. He suffered from lead poisoning, a common ailment among oil painters of the era due to the lead content in many pigments, particularly lead white. This affected his health significantly in his later years.

He continued to paint, but less prolifically. He married Olive Ethelwyn Cooper in 1920, but they later separated. He spent some time in Sydney in the 1920s. Despite his declining health, he remained a prominent figure in the Auckland art scene. He passed away in Auckland on July 11, 1947, at the age of 76.

After his death, his widow attempted to return some of his works to the Auckland City Art Gallery, but there was some institutional reluctance at the time, reflecting a period when his art was perhaps less fashionable. Some of these works were subsequently sold.

Legacy and Enduring Impact

Despite the fluctuations in his critical fortune, Charles Frederick Goldie's place in New Zealand art history is secure, albeit complex. For many years after his death, his work was somewhat marginalized by an art establishment more interested in modernism and landscape painting. However, a major retrospective exhibition of his work at the Auckland City Art Gallery in 1997, titled "C.F. Goldie: His Life & Painting," curated by Roger Blackley, sparked a significant re-evaluation. This exhibition brought his paintings to a new generation and highlighted both his technical mastery and the cultural significance of his subjects.

Today, Goldie's paintings command exceptionally high prices at auction, among the highest for any New Zealand artist. This market enthusiasm reflects a renewed public interest and appreciation, particularly for their historical and cultural value. His works are prominently displayed in major New Zealand galleries, including Te Papa Tongarewa (the Museum of New Zealand) in Wellington, the Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, and the Dunedin Public Art Gallery. The Auckland War Memorial Museum also holds a significant collection.

For Māori, the legacy is particularly potent. As mentioned, many iwi (tribes) and hapū (sub-tribes) regard Goldie's portraits of their ancestors as invaluable taonga. Exhibitions of his work often draw large numbers of Māori visitors, who come to connect with their tūpuna. The 1998 exhibition of Goldie's works at the Museum of Sydney, for instance, became a spiritual focal point for the Māori community there. These paintings are more than just art; they are embodiments of ancestral presence and cultural memory.

The debate surrounding Goldie's work continues, and this is perhaps a sign of its enduring power. He remains a figure through whom New Zealanders grapple with their colonial past, issues of representation, and the complex relationship between Pākehā and Māori. His meticulous portraits offer a window onto a pivotal period in New Zealand's history, capturing the dignity and mana (spiritual power, prestige) of Māori elders who faced the profound challenges of colonization.

Conclusion

Charles Frederick Goldie was an artist of considerable technical skill whose career was dedicated to a singular vision: the portraiture of Māori kaumātua. Trained in the rigorous academic traditions of Paris, he brought a European sensibility to a uniquely New Zealand subject. His paintings are at once beautiful, poignant, and problematic. They are treasured by many as vital records of tūpuna and as masterpieces of realist portraiture. Simultaneously, they are scrutinized for their role in perpetuating colonial narratives and for what they omit about Māori resilience and cultural continuity.

Goldie's art forces us to confront uncomfortable questions about history, power, and the ethics of representation. He was a man of his time, reflecting many of its prevailing attitudes, yet his best works transcend their historical context to offer compelling human documents. Whether viewed as a master chronicler, a romantic idealist, or an agent of colonial discourse, Charles Frederick Goldie remains an indispensable, if controversial, figure in the story of New Zealand art. His canvases continue to speak, to challenge, and to connect viewers with the faces of a past that profoundly shapes the present.