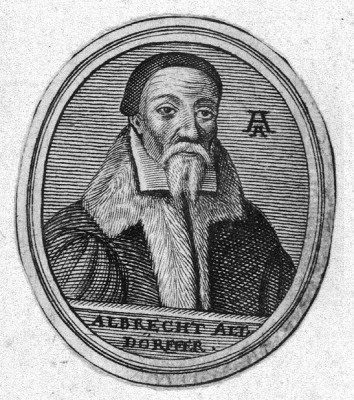

Albrecht Altdorfer stands as a towering figure in the German Renaissance, a multifaceted artist whose talents spanned painting, printmaking, engraving, and architecture. Active primarily in the early 16th century (circa 1480-1538), he is celebrated as a leading proponent, perhaps the most significant figure, of the Danube School of painting. His innovative approach, particularly his groundbreaking work in landscape painting, secured his place as one of the most original German artists of his time, leaving a lasting legacy that influenced generations to come.

Early Life and Civic Engagement in Regensburg

Born around 1480, likely in or near the Bavarian city of Regensburg, Altdorfer's life and career became inextricably linked with this vibrant center on the Danube River. While details of his earliest training remain obscure, his father, Ulrich Altdorfer, was also a painter and miniaturist, suggesting an early immersion in the artistic milieu. Albrecht emerges clearly in historical records in 1505 when he acquired citizenship rights in Regensburg. This marked the beginning of a long and prosperous period in the city.

His commitment to Regensburg extended beyond his artistic endeavors. Records show he purchased property, including a house and vineyards, indicating a degree of financial success and stability. Furthermore, Altdorfer became deeply involved in the city's civic life. He served Regensburg in official capacities, notably as the city architect (Stadtbaumeister), a role that involved overseeing municipal building projects and fortifications. His standing in the community was further solidified by his election to the city's Inner Council (Inner Rat), demonstrating the respect he commanded among his fellow citizens not just as an artist but as a public figure. He spent the vast majority of his productive life in Regensburg, dying there in 1538.

The Danube School and Artistic Context

Altdorfer is best known as the principal master of the Danube School (Donauschule or Donaustil), a circle of artists active in the Danube valley in Bavaria and Austria during the early 16th century. This group, which also included notable figures like Wolf Huber and Lucas Cranach the Elder (in his earlier phases), distinguished itself through a heightened interest in landscape. While religious and historical themes remained central, the Danube School artists imbued their works with expressive, often fantastical, depictions of the local forests and river scenery, giving nature an unprecedented prominence.

Altdorfer worked within the broader context of the Northern Renaissance, a period dominated in Germany by the towering figure of Albrecht Dürer. While Altdorfer was undoubtedly aware of Dürer's work and likely influenced by his technical mastery and thematic range, his artistic path diverged significantly, particularly in his emphasis on landscape. Similarly, he was a contemporary of other major German masters like Hans Holbein the Younger, renowned for his penetrating portraits, and Lucas Cranach the Elder, known for his courtly paintings and Reformation imagery.

Although contemporaries and part of the same artistic ferment, direct evidence of close personal collaboration or correspondence between Altdorfer and giants like Dürer or Holbein is lacking. Dürer, for instance, travelled to Italy and absorbed lessons from masters like Giovanni Bellini and Raphael, and studied the theories of Leonardo da Vinci, bringing a distinct Italianate influence to German art. Holbein achieved fame primarily through portraiture, developing a cool, objective style. Altdorfer, while potentially influenced by Dürer and Cranach, forged a unique style deeply rooted in the landscapes and atmosphere of the Danube region. His collaboration with Wolf Huber seems more direct, with both artists contributing significantly to the development of the Danube School's characteristic style.

Pioneering the Landscape Genre

Perhaps Altdorfer's most revolutionary contribution to Western art was his pioneering role in the development of landscape painting as an independent genre. Before him, landscape typically served merely as a backdrop for biblical, mythological, or historical narratives. Altdorfer, however, began to create works where the natural setting was the primary subject, imbued with mood and emotion.

He is credited with producing some of the earliest pure landscape paintings, devoid of any narrative figures, in the history of European art. A small panel painting like Landscape with Footbridge (c. 1518-1520) is often cited as a landmark example. Here, the intricate rendering of trees, water, and a rustic bridge under a dramatic sky becomes the sole focus. The human element is minimal, absorbed by the overwhelming presence of nature.

Even when depicting traditional subjects, Altdorfer often allowed the landscape to dominate the composition, using it to amplify the scene's emotional or spiritual resonance. The dense forests, soaring mountains, and atmospheric effects – dramatic sunsets, swirling mists, luminous twilight – in his works are not just settings but active participants in the drama. This approach contrasted sharply with the more structured, human-centric focus typical of the Italian Renaissance. While artists like the Flemish painter Joachim Patinir were also developing panoramic landscapes around the same time, Altdorfer's work is distinguished by its intense emotionalism and its focus on the specific character of the German forest. He captured the wildness and mystery of the natural world in a way few had before.

Mastery of Historical and Religious Themes

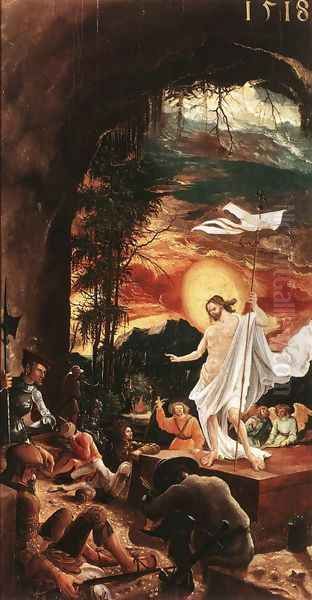

While a landscape innovator, Altdorfer remained deeply engaged with the traditional religious and historical subjects demanded by patrons. However, he approached these themes with his characteristic originality, often integrating them seamlessly with his powerful landscape visions. His religious works frequently possess an intimate, mystical quality, enhanced by the atmospheric settings.

His most famous work overall is undoubtedly The Battle of Alexander at Issus (1529). Commissioned by Duke Wilhelm IV of Bavaria as part of a series of historical battle paintings, this masterpiece depicts the victory of Alexander the Great over the Persian King Darius III in 333 BC. Yet, it transcends mere historical illustration. The painting is renowned for its breathtaking panoramic vista, an almost cosmic view encompassing vast armies, detailed terrain, and a spectacular sky with the sun setting and the moon rising simultaneously. The sheer number of figures, meticulously rendered, is staggering, conveying the epic scale of the conflict. Altdorfer masterfully blends historical narrative with a profound sense of landscape, creating a work of unparalleled complexity and visual drama. The accuracy of line and richness of color were highly praised.

Other significant religious and historical works demonstrate his range. Christ Taking Leave of His Mother (1518) focuses on the tender emotion between the figures, set within a characteristic landscape. The Legend of St. Sebastian (c. 1510-1518), part of a larger altarpiece, showcases his ability to integrate narrative action within a detailed architectural and natural setting. The Departure of St. Florian (c. 1518-1520) similarly places the saintly figure within a richly imagined environment. Works like The Birth of the Virgin and The Resurrection of Christ often feature innovative compositions, such as dramatic diagonal thrusts, and use light and celestial phenomena to heighten the spiritual intensity, prioritizing atmosphere and feeling alongside the narrative. His depictions of the Madonna and Child often place the figures in lush, enveloping landscapes, emphasizing a connection between the sacred and the natural world.

Innovations in Printmaking

Alongside his achievements in painting, Altdorfer was a highly accomplished and innovative printmaker. He worked proficiently in both woodcut and engraving, but he is particularly noted as one of incorporates the earliest artists, possibly the very first in Germany alongside Dürer, to explore the medium of etching on copper plates. Etching allowed for a freer, more sketch-like line compared to the meticulous labor of engraving, enabling artists to capture effects of light and atmosphere with greater spontaneity.

His etchings, often small in scale, are celebrated for their delicate detail, atmospheric qualities, and imaginative compositions. Many feature landscapes, further demonstrating his preoccupation with the natural world. Works like Landscape with a Double Spruce or landscape etchings featuring castles and ruins showcase his ability to evoke mood through line and tone. Religious subjects also appear in his etchings, such as The Stigmata of St. Francis, rendered with sensitivity and technical skill.

Altdorfer also produced numerous woodcuts, including illustrations and single-leaf prints. His woodcut Madonna and Child (1526) is a fine example of his work in this medium. His small, intricate engravings and etchings have led to his association with the "Little Masters" (Kleinmeister), a group of German printmakers active in the generation after Dürer, primarily in Nuremberg. This group, including artists like the brothers Hans Sebald Beham and Barthel Beham, and Georg Pencz, specialized in producing small-format prints, often featuring secular, mythological, or ornamental subjects, intended for a growing market of collectors. Altdorfer's prints share their technical refinement and small scale, though his thematic focus often remained distinct. His prints, like his paintings, are characterized by fine detail and a masterful handling of light and shadow.

Artistic Style and Techniques

Altdorfer's artistic style is marked by several key characteristics. Foremost is his intense feeling for nature and landscape, which often dominates his compositions and is rendered with expressive color and atmospheric effects. He favored dramatic lighting – sunsets, twilight, moonlight – to create moods ranging from idyllic and serene to mystical and turbulent. His colors are often rich and jewel-like, contributing to the emotional impact of his scenes.

His compositions can be complex and dynamic, particularly in works like The Battle of Alexander at Issus, which employs a high viewpoint and vast perspective. In his earlier works, figures sometimes display exaggerated poses or proportions, conveying intense emotion, a feature that connects him to late Gothic traditions even as he embraced Renaissance ideas. Later works show greater naturalism in figure drawing, but the expressive quality remains.

He demonstrated remarkable technical skill across different media. In painting, he worked primarily in oil on panel, achieving fine detail and luminous color. His mastery of printmaking techniques, especially etching, allowed him to explore line and tone with great subtlety. Overall, his art represents a unique fusion of late Gothic expressiveness, Renaissance humanism (particularly in the appreciation of nature), and a deeply personal, almost romantic, sensibility. His style blends naturalism with a powerful imagination.

Later Life and Legacy

Altdorfer remained a respected figure in Regensburg until his death on February 12, 1538. He left behind a significant body of work that continues to fascinate scholars and art lovers. His personal life remains somewhat enigmatic; despite his civic prominence, few details are known, and there is no definitive record of him having a wife or children. His artistic estate seems to have been handled by relatives.

His influence on subsequent generations of artists was profound, particularly in the realm of landscape painting. He effectively established landscape as a viable independent genre in German art, paving the way for later Northern European landscape specialists like Pieter Bruegel the Elder, whose works also often feature panoramic views and a keen observation of nature and human activity within it. The Danube School itself, though relatively short-lived, represented a significant regional development in the Northern Renaissance, and Altdorfer was its brightest star.

His innovative approach to religious imagery, emphasizing atmosphere and emotion through landscape, offered a distinct alternative to both Italian models and the more didactic art associated with the Reformation. His technical innovations in etching contributed to the development of that medium. Albrecht Altdorfer's legacy is that of a highly original master who expanded the thematic and expressive possibilities of art, leaving an indelible mark on the German Renaissance and the history of landscape painting.

Conclusion

Albrecht Altdorfer was far more than just a painter; he was an architect, a printmaker, a civic leader, and above all, an artistic visionary. As the leading master of the Danube School, he infused German Renaissance art with a unique sensitivity to the natural world. His pioneering efforts elevated landscape from mere background to a powerful subject in its own right, capable of conveying deep emotion and spiritual resonance. Through works like The Battle of Alexander at Issus and his intimate landscape etchings, Altdorfer demonstrated a remarkable synthesis of technical skill, imaginative power, and a profound connection to the world around him, securing his position as one of the most innovative and influential artists of his era.