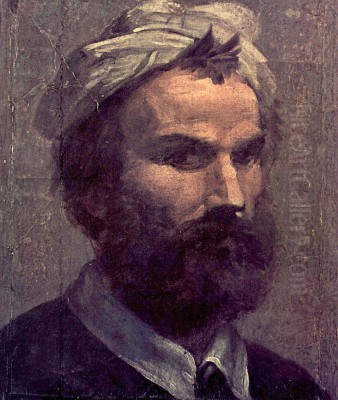

Domenico di Giacomo di Pace Beccafumi, often known simply as Domenico Beccafumi, stands as one of the most significant and individualistic artists of the Italian High Renaissance and early Mannerist periods. Active primarily in Siena, his birthplace, Beccafumi carved a unique niche for himself, blending the rich artistic traditions of his native city with the groundbreaking innovations emanating from Rome and Florence. His oeuvre, spanning painting, sculpture, and intricate pavement designs, is characterized by its vibrant, often unconventional use of color, dramatic lighting, elongated figures, and profound emotional intensity. As the last great master of the Sienese school, Beccafumi's work provides a fascinating bridge between the waning Gothic sensibilities of Siena and the emergent dynamism of Mannerism.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in Siena

Born around 1486 in Montaperti, a village near Siena, Domenico's early life was modest. Legend, as recounted by Giorgio Vasari in his "Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects," tells of a young shepherd boy named Domenico di Pace who displayed a prodigious talent for drawing, sketching figures in the sand while tending his flock. This raw ability caught the attention of Lorenzo Beccafumi, a wealthy Sienese citizen, who recognized the boy's potential. Lorenzo took him into his household, gave him his surname, and arranged for his formal artistic training in Siena.

In Siena, the young artist would have been immersed in a rich, albeit somewhat conservative, artistic environment. The Sienese school, with its deep roots in Byzantine art and its emphasis on decorative beauty, linearity, and devotional sentiment, had produced masters like Duccio di Buoninsegna, Simone Martini, and the Lorenzetti brothers (Pietro and Ambrogio) centuries earlier. While the revolutionary naturalism of the Florentine Renaissance had begun to permeate Sienese art through figures like Sassetta and Giovanni di Paolo, a distinct local flavor persisted. Beccafumi's initial training likely involved apprenticeship with a local master, where he would have learned the fundamentals of panel painting, fresco, and perhaps even the Sienese specialty of intricate gold-work. Some scholars suggest early contact with Sienese painters like Giacomo Pacchiarotti or Girolamo di Giovanni.

The Roman Sojourn: A Crucible of Influences

A pivotal moment in Beccafumi's development came with his journey to Rome, undertaken likely between 1510 and 1512. Rome at this time was the epicenter of the High Renaissance, a vibrant hub where artistic giants were reshaping the visual language of Western art. Here, Beccafumi encountered firsthand the monumental achievements of Michelangelo Buonarroti, particularly the recently unveiled sections of the Sistine Chapel ceiling, whose dynamic figures and dramatic power left an indelible mark. He also studied the harmonious compositions, graceful figures, and sophisticated classicism of Raphael Sanzio, then at work on the Vatican Stanze.

The experience in Rome was transformative. Beccafumi absorbed the lessons of classical sculpture, the principles of anatomical accuracy, and the ambitious scale of Roman artistic projects. Beyond Michelangelo and Raphael, he would have seen works by other leading artists. The influence of Fra Bartolomeo, a Florentine friar-painter known for his mastery of color, light, and devotional gravity, is also discernible in Beccafumi's subsequent work, suggesting a possible period of study or close observation in Florence either before or after his Roman stay. The works of Leonardo da Vinci, though primarily active elsewhere, would have been known through copies and their pervasive influence on central Italian art. Beccafumi's Roman experience equipped him with a new understanding of form, space, and expressive potential, which he would uniquely synthesize with his Sienese heritage.

Return to Siena: Forging a Unique Style

Upon his return to Siena around 1513, Beccafumi began to establish himself as a leading artist. He brought back with him the dynamism and monumentality of Roman art, but he did not simply imitate his influences. Instead, he filtered these experiences through his own artistic temperament and the enduring traditions of Sienese art. His style evolved into a highly personal form of Mannerism, characterized by elongated figures, often in contorted or elegant poses, a non-naturalistic use of color to heighten emotional impact, and a dramatic interplay of light and shadow that created an almost mystical atmosphere.

His contemporary in Siena, Giovanni Antonio Bazzi, known as Il Sodoma, was also a prominent figure, having arrived from Lombardy and bringing a softer, more Leonardesque style. While both artists contributed significantly to Sienese art of the period, and at times even collaborated or competed for commissions, Beccafumi's work generally exhibits a greater intensity, a more experimental approach to form and light, and a deeper, sometimes unsettling, psychological depth. Another Sienese artist of note from this period was Baldassare Peruzzi, who, like Beccafumi, also spent time in Rome and absorbed High Renaissance principles, though Peruzzi's work often leaned more towards architectural and perspectival concerns.

The Essence of Beccafumi's Mannerism

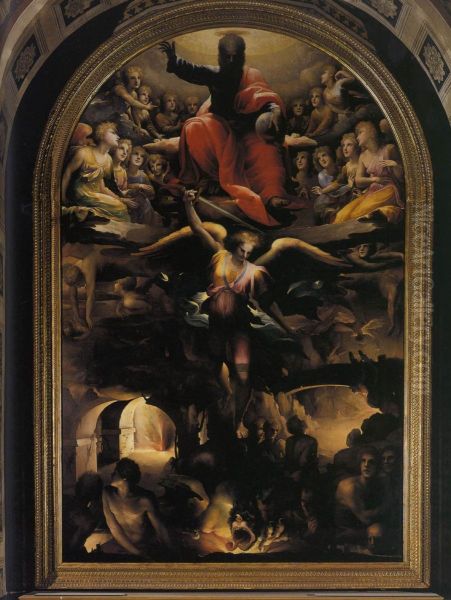

Mannerism, the dominant artistic style in Italy from roughly 1520 to the end of the 16th century, emerged as a reaction to the harmonious classicism and idealized naturalism of the High Renaissance. Artists like Beccafumi, Pontormo, Rosso Fiorentino in Florence, and Parmigianino in Parma, sought new avenues for expression. They often prioritized elegance, artifice, and emotional intensity over strict adherence to natural appearances. Key characteristics of Mannerism evident in Beccafumi's work include:

Elongated Proportions: Figures are often stretched and slender, contributing to an air of grace or spiritual tension.

Complex Compositions: Space can be ambiguous or compressed, with figures arranged in dynamic, sometimes unstable, groupings.

Vivid and Unconventional Color: Beccafumi was a master colorist, employing vibrant, often acidic or iridescent hues that departed from naturalistic representation to create specific moods or highlight symbolic meanings.

Dramatic Use of Light (Chiaroscuro): He exploited strong contrasts between light and shadow to model forms, create a sense of volume, and imbue his scenes with a theatrical or visionary quality. This often resulted in a flickering, almost ethereal light.

Emotional Intensity: His figures convey powerful emotions, from ecstatic devotion to profound anguish, often through expressive gestures and facial features.

Beccafumi's Mannerism retained a distinctly Sienese "provincialism," not in a pejorative sense, but rather as an indication of his continued engagement with local artistic traditions, particularly the Sienese love for decorative richness and spiritual fervor. This fusion of Sienese sensibility with Roman grandeur and Mannerist innovation is what makes his art so compelling and unique.

Mastery in Diverse Media: Painting

Beccafumi was a versatile artist, excelling in various forms of painting, from large-scale frescoes and altarpieces to smaller devotional panels.

Religious Narratives and Altarpieces

Many of Beccafumi's most celebrated paintings are religious altarpieces and narrative scenes. One of his early masterpieces upon returning to Siena is The Stigmatization of St. Catherine (c. 1513-1515, Pinacoteca Nazionale, Siena), created for the Olivetan convent of Santa Caterina. The painting depicts St. Catherine of Siena receiving the stigmata in a dramatically lit, visionary landscape. The elongated figures, the intense emotional expressions, and the almost supernatural glow demonstrate his emerging Mannerist tendencies.

Another significant work is The Marriage of the Virgin (c. 1517-1518), originally for the Oratorio di San Bernardino and now in the Pinacoteca Nazionale, Siena. This piece showcases his sophisticated handling of a multi-figure composition and his characteristic use of vibrant, almost shot, colors. The figures, while graceful, possess a nervous energy typical of early Mannerism.

His Trinity with Saints (1513, Pinacoteca Nazionale, Siena) is another early Sienese commission, notable for its powerful forms and the influence of Roman High Renaissance models, particularly Michelangelo, in the depiction of God the Father.

Later works, such as the Madonna with the Infant Christ and St. John the Baptist (c. 1540, Pinacoteca Nazionale, Siena), show a mature command of his style. The figures are elegant and refined, bathed in a soft, mystical light. The emotional connection between the figures is palpable, a hallmark of Beccafumi's ability to convey deep spiritual feeling. The Holy Family with Angels (c. 1545-1550, Princeton University Art Museum) further exemplifies this late style, with its tender intimacy and sophisticated color harmonies.

Other notable paintings include the Birth of the Virgin (c. 1540-1543, Pinacoteca Nazionale, Siena), which displays a complex architectural setting and a lively narrative, and various depictions of the Madonna and Child, such as the one from around 1530 now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. These works consistently demonstrate his ability to infuse traditional religious themes with a fresh, dynamic, and emotionally resonant vision.

Frescoes and Monumental Works

Beccafumi was also a highly accomplished fresco painter. His most significant fresco cycle was executed in the Sala del Concistoro of the Palazzo Pubblico (the Sienese town hall) between 1529 and 1535. These frescoes depict scenes of civic virtue and justice drawn from Greek and Roman history, such as the Justice of Seleucus, The Sacrifice of Codrus, and The Punishment of Spurius Cassius. The compositions are complex and dynamic, filled with muscular, active figures that recall Michelangelo, yet imbued with Beccafumi's characteristic use of flickering light and vibrant color. These works served as powerful allegories for the Sienese Republic.

He also contributed to the decoration of the Oratorio di San Bernardino in Siena, working alongside Il Sodoma and Girolamo del Pacchia. Here, he painted scenes from the life of the Virgin, including a notable Visitation. These frescoes further highlight his skill in narrative composition and his ability to create dramatic and emotionally engaging scenes on a large scale. Works like The Story of Elijah and Moses Making Water Flow from the Rock are often cited among his powerful narrative frescoes, showcasing his ability to handle complex figural groups and dramatic storytelling.

Innovations in Printmaking: The Chiaroscuro Woodcuts

Beyond painting, Beccafumi made significant contributions to the art of printmaking, particularly in the medium of chiaroscuro woodcut. This technique, pioneered by artists like Ugo da Carpi in Italy (who himself was influenced by German printmakers like Lucas Cranach the Elder and Hans Burgkmair), involves using multiple woodblocks, each inked with a different tone of the same color, to create an image with a greater sense of depth, volume, and painterly effect than a simple line block.

Beccafumi was one of the earliest Italian artists to explore the expressive potential of chiaroscuro woodcuts. His prints, often depicting single figures or small groups, are characterized by their bold designs, dramatic lighting, and a remarkable sense of plasticity. He often cut his own blocks, giving his prints a directness and energy. Some sources suggest an interest in alchemy and mysticism, which may have informed the enigmatic quality of some of his graphic works, such as The Alchemist and the Laborer (c. 1525-1540). His prints, though relatively few in number (around nine purely chiaroscuro woodcuts are known), are highly prized for their artistic quality and technical innovation. They demonstrate his mastery of light and shadow in a different medium, achieving effects that rival the tonal subtleties of his paintings.

Beccafumi the Sculptor: Form in Three Dimensions

Beccafumi's versatility extended to sculpture, primarily in bronze. While fewer of his sculptural works survive or are definitively attributed, his skill in this medium is evident. His most famous sculptural commission consists of eight bronze angels (c. 1548-1550) for the pillars of the presbytery of the Siena Cathedral. These elegant, elongated figures, with their flowing drapery and expressive gestures, are fully in keeping with his Mannerist painting style. They demonstrate his ability to translate his painterly concerns with form, movement, and emotional intensity into three dimensions. His late career saw an increased focus on bronze casting, indicating a deep engagement with the technical and artistic challenges of sculpture.

The Siena Cathedral Pavement: A Tapestry in Stone

Perhaps Beccafumi's most unique and enduring contribution to Sienese art is his extensive work on the magnificent inlaid marble pavement of the Siena Cathedral (Duomo di Siena). This extraordinary floor, created over several centuries (from the 14th to the 19th), features 56 panels depicting biblical scenes, allegories, and sibyls, executed using a complex technique of marble intarsia (sgraffito and opus sectile).

Beccafumi designed and supervised the execution of numerous panels for the pavement between 1517 and 1546. His designs, which include scenes from the Old Testament such as The Sacrifice of Isaac, Moses Striking the Rock, The Story of Elijah, and scenes from the life of Ahab, are among the most dynamic and artistically sophisticated in the entire pavement. He brought his Mannerist sensibility to this challenging medium, creating compositions of great complexity, with dramatic perspectives, powerful figures, and a remarkable sense of movement and depth, all achieved through the careful selection and arrangement of different colored marbles. His contributions transformed the later sections of the pavement, moving away from the more linear and Gothic style of earlier panels towards a more painterly and monumental approach. This work stands as a testament to his innovative spirit and his ability to master diverse artistic techniques.

Interactions and Artistic Milieu

Throughout his career, Beccafumi interacted with numerous contemporary artists, both in Siena and during his time in Rome. In Siena, his relationship with Il Sodoma was significant. While their styles differed, they were the two dominant artistic personalities in the city for several decades, often competing for the same prestigious commissions but also occasionally collaborating, as at the Oratorio di San Bernardino. Girolamo del Pacchia was another Sienese contemporary involved in these collaborative projects.

His Roman sojourn brought him into contact with the towering figures of Michelangelo and Raphael, whose influence was profound. He would also have been aware of the work of other artists active in Rome, such as Sebastiano del Piombo, who combined Venetian color with Roman monumentality. The influence of Florentine artists like Fra Bartolomeo and Andrea del Sarto, a leading figure of early Florentine Mannerism, is also evident, suggesting Beccafumi was well-attuned to developments in nearby artistic centers.

The broader Italian artistic landscape included Venetian masters like Giorgione and Titian, whose revolutionary use of color and light was transforming painting in the Veneto. While direct influence is harder to trace, the general artistic ferment of the period, with ideas and styles traveling between cities, would have contributed to the environment in which Beccafumi worked. His art, in turn, influenced subsequent generations of Sienese artists, such as Marco Pino (Marco da Siena), who carried Sienese Mannerism to Naples, and later figures like Alessandro Casolani and Ventura Salimbeni, who continued to work in a style that owed a debt to Beccafumi's innovations.

The rumored anecdote of Beccafumi being murdered for possessing the "secret of oil painting" is likely apocryphal, as oil painting techniques were widely known by this time. However, such stories, even if untrue, often arise around artists perceived as exceptionally skilled or innovative, reflecting the high esteem and perhaps a touch of mystery surrounding their abilities.

Later Years and Enduring Legacy

Domenico Beccafumi remained active in Siena for most of his life, becoming the official painter of the Sienese Republic and undertaking numerous commissions for churches, confraternities, and private patrons. He continued to refine his distinctive style, producing works of profound spiritual intensity and artistic brilliance until his death in Siena on May 18, 1551.

His legacy is multifaceted. As the last great painter of the Sienese school, he brought its long and distinguished tradition to a vibrant close, infusing it with the new energies of Mannerism. He was a pioneer in the use of expressive light and color, creating works that were both visually stunning and emotionally compelling. His contributions to the Siena Cathedral pavement are unique in the history of art, demonstrating an extraordinary ability to adapt his painterly vision to the demanding medium of marble intarsia. His chiaroscuro woodcuts mark him as an important innovator in printmaking.

While sometimes overshadowed by his Florentine and Roman contemporaries in broader art historical narratives, Beccafumi is increasingly recognized for his originality and the distinctive power of his art. His work embodies the transition from High Renaissance ideals to the more subjective and expressive concerns of Mannerism, all filtered through a deeply personal and Sienese sensibility. He left an indelible mark on the art of Siena and stands as a key figure in the complex and fascinating landscape of 16th-century Italian art.

Conclusion

Domenico Beccafumi was an artist of remarkable talent, versatility, and originality. From his humble beginnings, he rose to become a dominant figure in Sienese art, skillfully navigating the artistic currents of his time. His ability to synthesize the grandeur of Roman High Renaissance art with the decorative traditions of Siena and the emerging tenets of Mannerism resulted in a body of work that is both unique and profoundly influential. Whether in his emotionally charged paintings, his dynamic frescoes, his innovative prints, his elegant sculptures, or his breathtaking pavement designs for the Siena Cathedral, Beccafumi consistently demonstrated a mastery of technique and a visionary artistic imagination. He remains a testament to the enduring vitality of Sienese art and a crucial voice in the chorus of Italian Mannerism.