Albrecht Dürer stands as a colossus in the history of art, arguably the most significant artist of the Northern Renaissance. Born in the vibrant heart of the Holy Roman Empire, he was a painter, printmaker, engraver, mathematician, and theorist whose prodigious talent and intellectual curiosity bridged the late Gothic world with the burgeoning humanism sweeping up from Italy. His influence radiated across Europe, transforming the artistic landscape, particularly in the realm of printmaking, which he elevated to an unprecedented level of sophistication and expressive power. Dürer was more than an artist; he was a keen observer, a technical innovator, a savvy businessman, and a profound thinker whose life and work continue to fascinate and inspire centuries later.

Early Life and Formative Years in Nuremberg

Albrecht Dürer entered the world on May 21, 1471, in Nuremberg, then a prosperous Free Imperial City and a major center of commerce, craftsmanship, and humanist thought within the Holy Roman Empire. His origins were rooted in craftsmanship; his father, Albrecht Dürer the Elder, was a successful goldsmith who had migrated from Ajtós, near Gyula in Hungary, around 1455. Upon settling in Nuremberg, the elder Dürer Germanized his Hungarian name, Ajtósi (meaning "door-maker"), to the German equivalent, Türer, which eventually became Dürer. Albrecht the Younger was the third child and second son among the eighteen children his father had with Barbara Holper, the daughter of his own master goldsmith.

Growing up in a bustling artisan household provided Dürer with his initial training. He learned the fundamentals of metalworking and design in his father's workshop, skills that would prove invaluable in his later mastery of engraving. Even as a child, his exceptional talent for drawing was evident. A silverpoint self-portrait made at the age of thirteen already displays remarkable confidence and observational skill. His family, though middle-class rather than aristocratic, ensured he received a good education, including the study of Latin, which opened doors to humanist learning.

![The Martyrdom Of St. John (from Apocalypse Series), 1498 [bartsch 61; Meder 164] by Albrecht Durer](https://www.niceartgallery.com/imgs/3088700/m/albrecht-durer-the-martyrdom-of-st-john-from-apocalypse-series-1498-bartsch-61-meder-164-ff421777.jpg)

Recognizing his son's inclination towards drawing and painting rather than goldsmithing, Dürer the Elder arranged for him to be apprenticed in 1486 to Michael Wolgemut, Nuremberg's leading painter at the time. Wolgemut's large workshop produced a variety of works, including altarpieces and, significantly, woodcut illustrations for books. This environment provided Dürer with thorough training in painting, drawing, and, crucially, the techniques of woodcut design. Wolgemut, working in a late Gothic style, imparted the traditions of Northern European art, but his workshop's involvement with the burgeoning printing industry exposed Dürer to the potential of reproducible media. His apprenticeship also included foundational studies in mathematics and theory, laying the groundwork for his lifelong interest in proportion, perspective, and geometry.

The Journeyman Years and the Lure of Italy

Following the completion of his apprenticeship around 1490, Dürer embarked on his Wanderjahre, or journeyman years, a traditional period of travel for craftsmen to gain experience and broaden their horizons. Lasting until 1494, these travels took him through various German-speaking lands. He likely visited Frankfurt and potentially the Netherlands before spending considerable time in Colmar, hoping to work with Martin Schongauer, the leading Northern European engraver. Though Schongauer died shortly before Dürer's arrival, he was welcomed by the master's brothers, also artists and goldsmiths.

His travels then took him to Basel, Switzerland, another major center of printing and humanism. Here, Dürer further honed his skills in woodcut design, contributing illustrations to several publications, including Sebastian Brant's satirical work, Das Narrenschiff (The Ship of Fools). These early woodcuts already show a dynamism and complexity that surpassed much contemporary work. His time away exposed him to different artistic styles and intellectual currents, refining his craft and expanding his network.

In 1494, Dürer returned briefly to Nuremberg to marry Agnes Frey, the daughter of a respectable artisan, in an arrangement made during his absence. However, mere months after his wedding, Dürer set off again, this time undertaking a far more ambitious journey – his first trip across the Alps to Italy. Prompted perhaps by an outbreak of plague in Nuremberg, but certainly driven by artistic curiosity, this journey marked a pivotal moment in his career. He traveled to Venice, the vibrant gateway between Northern Europe and the Italian Renaissance.

In Italy, Dürer encountered firsthand the revolutionary artistic developments that had been transforming art south of the Alps. He studied the works of Italian masters like Andrea Mantegna, whose engravings particularly impressed him with their classical forms and rigorous perspective. He absorbed the Italian emphasis on human anatomy, proportion, and the revival of classical antiquity. During this trip, he also began creating a series of stunning watercolor landscapes, remarkable for their time in their focus on topography and atmospheric effects. He also likely began his lifelong friendship with the Nuremberg humanist Willibald Pirckheimer, who was studying in Italy at the time and who would become a crucial intellectual companion.

Establishing Mastery: The Printmaking Revolution

Returning to Nuremberg in 1495, Dürer established his own workshop. While he continued to paint, it was through the medium of printmaking – both woodcut and engraving – that he rapidly achieved widespread fame. He possessed an unparalleled ability to translate complex ideas and detailed observations into the linear language of black and white. He treated printmaking not merely as a reproductive craft but as a major art form capable of profound expression.

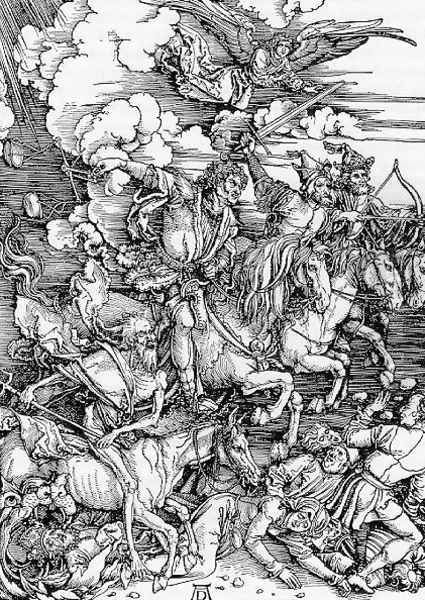

His groundbreaking achievement came in 1498 with the publication of his large-format woodcut series illustrating the Apocalypse. These fifteen prints, depicting scenes from the Book of Revelation, were unprecedented in their scale, dramatic intensity, and technical virtuosity. Works like The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse combined terrifying visionary power with intricate detail, showcasing Dürer's mastery of composition and his ability to convey movement and emotion through line alone. The series was an immediate success, circulating widely and establishing Dürer's reputation across Europe.

Dürer approached engraving with the same innovative spirit. Using the burin, a sharp steel tool, to incise lines directly into a copper plate, he achieved levels of detail, tonal subtlety, and textural richness previously unseen in the medium. He explored a wide range of subjects, from religious and mythological scenes to genre studies and portraits. His prints were not only artistic triumphs but also commercially successful. Dürer understood the market, often publishing series himself and controlling their distribution. He famously adopted his distinctive 'AD' monogram, effectively branding his work and guarding against plagiarism – an early form of copyright protection.

Around this period and in the early 1500s, he produced some of his most celebrated individual prints. He continued to explore religious themes, but also delved into allegorical and secular subjects. His technical brilliance allowed him to render diverse textures – fur, foliage, armor, flesh – with astonishing realism. He was pushing the boundaries of what could be achieved in print, influencing contemporaries and setting a standard for generations to come.

The Celebrated Master Engravings and Second Italian Journey

The period between his return from the first Italian trip and his departure for the second saw Dürer consolidate his position as the leading artist in Nuremberg and a figure of international renown. He continued to produce significant paintings, including several self-portraits that reveal a growing self-awareness and confidence. His famous 1500 self-portrait, presenting himself frontally in a manner previously reserved for depictions of Christ, remains a powerful statement of artistic identity and ambition, though some contemporaries and later critics debated its perceived conceit.

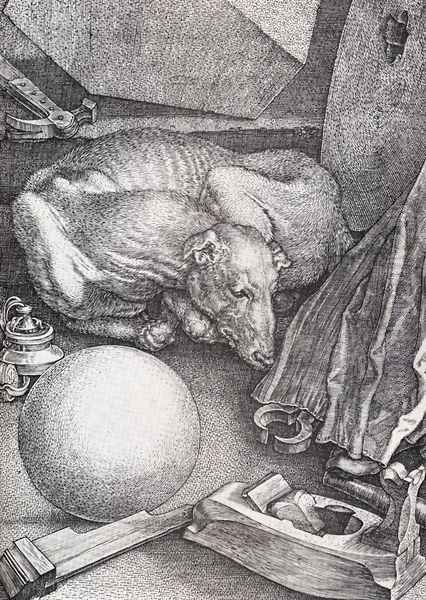

However, it was arguably in engraving that he reached his zenith during the years leading up to and following his second Italian journey. In 1513 and 1514, he created three engravings known as his Meisterstiche (Master Engravings): Knight, Death and the Devil (1513), Saint Jerome in His Study (1514), and Melencolia I (1514). These works represent the pinnacle of his engraving technique and are imbued with complex symbolism and intellectual depth.

Knight, Death and the Devil depicts a steadfast Christian knight riding through a dark valley, undeterred by the grotesque figures of Death and the Devil. It is often interpreted as an allegory of moral fortitude. Saint Jerome in His Study presents a serene image of the scholar saint peacefully at work in his meticulously rendered, light-filled room, an emblem of contemplative spiritual life. Melencolia I, perhaps the most enigmatic of the three, portrays a winged allegorical figure surrounded by symbols of geometry, craftsmanship, and intellectual pursuits, yet seemingly paralyzed by inaction and gloom. Its precise meaning remains debated, touching on themes of artistic creation, intellectual frustration, and the nature of melancholy itself.

In 1505, Dürer embarked on his second journey to Italy, again heading primarily to Venice, where he stayed until 1507. This time, he arrived not as an unknown student but as a celebrated master. His prints were already well-known and admired, though sometimes copied without permission, leading to famous disputes. He interacted with prominent Venetian artists, including the elderly master Giovanni Bellini, whom Dürer greatly respected. He may also have encountered younger luminaries like Giorgione and Titian, absorbing the Venetian school's emphasis on color and light.

During this stay, he painted the Feast of the Rose Garlands (1506) for the German merchant community in Venice, a large altarpiece demonstrating his ability to synthesize Northern detail with Italian compositional harmony and color. He also produced other paintings and continued his studies of perspective and human proportion, seeking the theoretical underpinnings of ideal beauty. His letters back to Willibald Pirckheimer during this period provide fascinating insights into his experiences, his pride in his German identity, and his sometimes-fraught interactions with Italian artists.

Imperial Patronage and Theoretical Pursuits

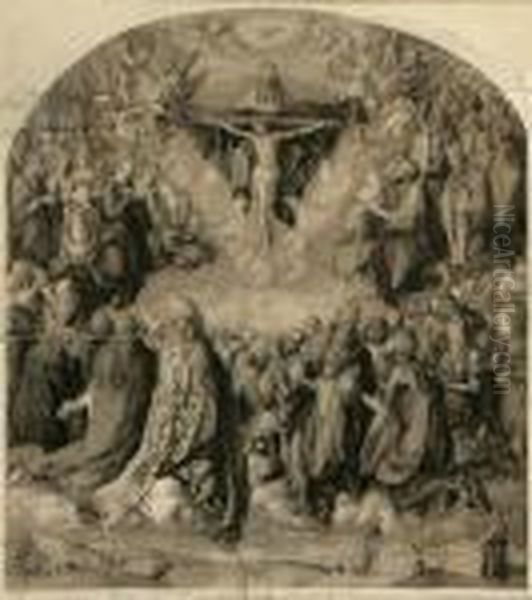

Upon his return to Nuremberg in 1507, Dürer was at the height of his fame. He continued to receive prestigious commissions for paintings, including the Adoration of the Trinity (Landauer Altarpiece, 1511), a complex and brilliantly colored work. His reputation attracted the attention of the highest echelons of society. From around 1512, he began working for the Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I.

His commissions for Maximilian included contributions to monumental print projects like the Triumphal Arch and the Triumphal Procession, vast composite woodcuts involving numerous artists but largely designed and overseen by Dürer. These works were intended as elaborate propaganda, celebrating the Emperor and his lineage. Dürer also painted several portraits of Maximilian. This imperial patronage brought him prestige and a degree of financial security, including an annual pension granted by the Emperor.

Alongside his prolific artistic output, Dürer increasingly dedicated himself to theoretical studies. He was driven by a Renaissance desire to understand the rational principles underlying art, particularly the depiction of the human form and the creation of convincing spatial illusions. He believed that art should be grounded in scientific knowledge, especially geometry and the study of human proportions. He meticulously measured human bodies, seeking mathematical formulas for ideal beauty, though he eventually concluded that beauty lay in variety.

These investigations culminated in the publication of several influential books towards the end of his life. His Underweysung der Messung mit dem Zirkel und Richtscheyt (Manual of Measurement with Compass and Ruler), published in 1525, was a practical guide to geometry for artists and artisans, covering topics like perspective, regular polygons, and the construction of letters. It was the first such book published in German and aimed to provide German artists with the theoretical knowledge readily available to their Italian counterparts.

His most extensive theoretical work was Vier Bücher von Menschlicher Proportion (Four Books on Human Proportion), published posthumously in 1528, shortly after his death. This comprehensive treatise presented his systematic study of human anatomy and proportion, illustrating a wide variety of male and female body types. These books codified his decades of research and had a lasting impact on artistic training and theory in Northern Europe, demonstrating his commitment to elevating the intellectual status of the artist. His approach reflected the broader Renaissance synthesis of art and science, seen also in the work of figures like Leonardo da Vinci.

The Netherlands Journey and Later Years

Following the death of Emperor Maximilian I in 1519, Dürer's imperial pension was jeopardized. To secure its confirmation from the new Emperor, Charles V, and also driven by a desire to see the sights and meet fellow artists, Dürer embarked on his final major journey, traveling to the Netherlands with his wife Agnes from 1520 to 1521. His detailed travel diary from this trip provides an invaluable record of his experiences, observations, and interactions.

He attended Charles V's coronation in Aachen and visited numerous cities, including Antwerp, Brussels, Bruges, and Ghent. He was received with honor by local dignitaries, artists, and scholars. He met prominent figures like the humanist Erasmus of Rotterdam (whose portrait he sketched) and fellow artists such as Quentin Matsys and Joachim Patinir. He recorded his admiration for the works of earlier Netherlandish masters like Jan van Eyck and Rogier van der Weyden.

A particularly significant encounter was with the talented younger Dutch engraver Lucas van Leyden. The two artists met, exchanged prints, and clearly held mutual respect, representing a key moment of interaction between the German and Netherlandish schools of printmaking. Dürer's diary meticulously documents his expenses, sales of prints (which helped finance the trip), gifts received and given, and his fascination with exotic objects he encountered, such as whale bones and artifacts from the New World.

The journey was not without hardship. Dürer contracted an illness, possibly malaria, during a trip to the marshy region of Zeeland (where he had hoped to see a stranded whale), which likely plagued him for the rest of his life and may have contributed to his death. His diary also records a perilous incident during a storm at sea near Arnemuiden. Despite these challenges, the trip was a success in securing his pension and further cementing his international connections.

Returning to Nuremberg in 1521, Dürer entered the final phase of his career. The religious turmoil of the Protestant Reformation was now profoundly affecting Nuremberg, which officially adopted Lutheranism in 1525. Dürer himself was deeply religious and sympathetic to Martin Luther's cause, though his exact theological position remained moderate. His later works reflect this intense religious climate. His final major paintings, the monumental panels known as the Four Apostles (1526), depicting Saints John, Peter, Mark, and Paul, are often seen as a testament to his Lutheran faith, presented as powerful warnings against false prophets and emphasizing the centrality of the Bible. He gifted these panels to the Nuremberg city council.

Personal Life, Character, and Hidden Depths

Beyond the public figure and celebrated artist, Dürer's writings, particularly his letters and the Netherlands diary, offer glimpses into his personality and private life. He emerges as a complex individual: diligent, intellectually curious, proud of his craft, and possessing a keen business sense. He carefully managed the production and sale of his prints, understanding their market value and ensuring his financial independence. His use of the 'AD' monogram was a mark of quality and authorship in an era when artistic property was ill-defined.

His writings reveal a man observant of the world around him, interested in everything from the cost of food to exotic animals (like the rhinoceros he famously depicted in a woodcut based on a sketch and description, having never seen one himself) to the customs of foreign lands. He possessed a certain directness and occasional humor. He valued friendships, maintaining a long and intellectually stimulating correspondence with Willibald Pirckheimer.

Yet, there were also shadows. His Meisterstiche, particularly Melencolia I, hint at inner struggles and periods of introspection or perhaps depression, conditions sometimes linked to the "melancholic" temperament traditionally associated with artistic genius. His health was often precarious, especially after the illness contracted in the Netherlands. His marriage to Agnes Frey appears to have been childless and, according to some interpretations of Pirckheimer's later writings (which may be biased), perhaps not entirely happy, though Agnes was involved in managing the workshop's sales.

Controversies and unresolved questions surround some aspects of his life and work. The full meaning of Melencolia I remains elusive, a puzzle box of Renaissance symbolism. His 1500 self-portrait continues to spark discussion about artistic ego and the changing status of the artist. His relationship with the contemporary religious debates, particularly concerning Jewish texts (as seen in the context of the Johannes Pfefferkorn controversy, a complex issue involving Dürer's humanist circle), suggests engagement with the turbulent intellectual currents of his time. Modern scientific analysis, using X-rays and infrared reflectography, continues to reveal hidden layers and underdrawings in his paintings, offering new insights into his working methods.

Legacy and Enduring Influence

Albrecht Dürer died in Nuremberg on April 6, 1528, at the age of 56. His passing was mourned throughout the city and the wider world of art and learning. His friend Pirckheimer composed a poignant epitaph: "Whatever was mortal of Albrecht Dürer lies beneath this mound." His legacy, however, proved immortal.

Dürer's impact on the development of art, particularly in Northern Europe, was immense and multifaceted. He effectively synthesized the detailed realism and expressive intensity of the Northern Gothic tradition with the Italian Renaissance's emphasis on classical form, perspective, and humanism. He demonstrated that German art could rival that of Italy in sophistication and intellectual depth.

His greatest and most revolutionary contribution lay in printmaking. He transformed both woodcut and engraving from relatively minor crafts into major independent art forms. His technical mastery, compositional innovation, and expressive range set a standard that profoundly influenced subsequent generations of printmakers across Europe, including figures like Lucas van Leyden in the Netherlands and Marcantonio Raimondi in Italy (who famously copied Dürer's prints, sometimes leading to disputes but also spreading his compositions). His prints circulated widely, disseminating his style and iconography far more effectively than paintings could.

His theoretical writings on measurement and proportion provided a crucial foundation for artistic education in Germany and beyond, promoting the idea of the artist as an intellectual and theorist, not just a craftsman. His intense self-scrutiny, evident in his numerous self-portraits, contributed to the development of the genre and reflected the growing Renaissance emphasis on individual identity.

Dürer's influence extended beyond his immediate successors like Hans Baldung Grien or Albrecht Altdorfer. His work continued to be studied and admired by artists in later centuries, from the Mannerists to the Romantics, who saw in him a quintessential German genius. His technical brilliance, intellectual rigor, and profound engagement with the spiritual and cultural issues of his time ensure his enduring status as one of the pivotal figures of the Renaissance and a master artist for the ages. His fusion of meticulous observation, technical perfection, and intellectual depth created a body of work that remains as compelling and relevant today as it was five centuries ago.