Aleksei Gavrilovich Venetsianov stands as a pivotal figure in the history of Russian art, a painter who tenderly and profoundly shifted the focus of artistic representation towards the everyday life of the Russian peasantry and the serene beauty of the native landscape. Active during the first half of the 19th century, a period of burgeoning national consciousness in Russia, Venetsianov carved a unique path, distinct from the prevailing academic classicism and romantic grandeur. He is celebrated not only for his idyllic and humane depictions of rural existence but also for his significant role as an educator, nurturing a generation of artists who would further explore themes of Russian identity.

Early Life and Artistic Beginnings

Aleksei Venetsianov was born in Moscow on February 18 (Old Style: February 7), 1780. His family background was modest; his father, Gavrila Yuryevich Venetsianov, was a merchant of Greek descent, reportedly involved in selling goods like berries and tulips. His mother was Anna Lukinichna (née Kalashnikova). This merchant-class upbringing, while not impoverished, was certainly outside the aristocratic circles that often produced or patronized artists at the time.

From a young age, Venetsianov displayed a keen interest in drawing. His early artistic education was largely informal. He initially worked as a clerk in Moscow, and later as a land surveyor. However, his passion for art led him to St. Petersburg around 1802. In the imperial capital, he sought out opportunities to develop his skills. He is known to have copied paintings in the Hermitage, a common practice for aspiring artists to learn from the Old Masters.

A significant early influence and mentor was Vladimir Borovikovsky (1757–1825), a leading portraitist of the era, known for his sentimental and elegant depictions of the Russian nobility. Venetsianov lived in Borovikovsky's house for a period and undoubtedly absorbed much from the established master, particularly in the realm of portraiture. However, Venetsianov's artistic temperament would eventually lead him down a different thematic path.

Entry into the Art World and Early Works

Venetsianov's initial forays into the public art scene included portraiture and, notably, caricature. Around 1808, he attempted to publish a "Journal of Caricatures," which was swiftly banned by the censors, perhaps due to its satirical edge being deemed too sharp for the authorities. During the Napoleonic Wars, particularly the Patriotic War of 1812, he produced patriotic caricatures targeting Napoleon and the French invaders, which found a more receptive audience.

His skill in portraiture, however, earned him official recognition. In 1811, Venetsianov was named an "appointed artist" by the Imperial Academy of Arts for his Self-Portrait (1811, Russian Museum). Later that same year, he was elevated to the rank of Academician for his Portrait of K. I. Golovachevsky and Younger Pupils of the Academy of Arts (1811, Russian Museum). Kirill Golovachevsky was an inspector at the Academy, and the painting demonstrates Venetsianov's growing mastery in capturing likeness and character, as well as complex group compositions. These early successes were primarily within the established genres favored by the Academy.

Other notable portraitists of this era, whose work Venetsianov would have been aware of, include Dmitry Levitzky (1735–1822), Borovikovsky's own teacher and a towering figure of 18th-century Russian portraiture, and Orest Kiprensky (1782–1836), a contemporary celebrated for his Romantic portraits that delved into the psychological depths of his sitters. Venetsianov's portrait style, while competent, was perhaps less overtly Romantic than Kiprensky's, often imbued with a gentle directness.

The Turn to Rural Life: The Safonkovo Period

A decisive shift in Venetsianov's life and art occurred around 1819. He resigned from civil service, left St. Petersburg, and settled in the small estate of Safonkovo in the Tver Governorate. This move was not merely a change of scenery but a profound reorientation of his artistic vision. It was here, immersed in the rhythms of rural life, that Venetsianov found his true calling: depicting the Russian peasant and the Russian land.

This decision was radical for its time. While peasant themes had appeared in Russian art before, they were often treated as exotic, picturesque, or as background elements in grander narratives. Venetsianov, however, approached his peasant subjects with an unprecedented empathy and dignity, seeking to capture the poetry and quiet nobility of their existence. He was less interested in the dramatic or the anecdotal, and more in the harmonious relationship between people and their environment.

His commitment to this new direction was total. He dedicated himself to observing the peasants at their daily tasks, the changing seasons, and the subtle play of light across the fields and within their humble dwellings. This period marked the true beginning of what is often called the "Venetsianov School" – not just in terms of his students, but in terms of a distinct artistic philosophy.

Artistic Style and Thematic Concerns

Venetsianov's style is characterized by its lyrical realism, its gentle humanism, and its keen observation of light and atmosphere. He sought to portray his subjects with truthfulness, yet his vision was often imbued with a sense of harmony and idealization. His peasants are typically depicted as healthy, serene, and intrinsically connected to the land they cultivate. This was a departure from later Realist painters like Vasily Perov (1834–1882), who would often highlight the hardships and social injustices faced by the peasantry.

Venetsianov was particularly interested in the effects of light, both outdoors ("en plein air," though much of his work was likely finished in the studio based on outdoor studies) and indoors. He masterfully rendered the soft, diffused light of the Russian countryside and the interplay of light and shadow in peasant interiors. His color palettes are often harmonious and subdued, reflecting the natural tones of the environment.

His compositions are typically calm and balanced, emphasizing a sense of order and tranquility. He often placed his figures centrally, giving them a quiet monumentality. There's a distinct lack of overt narrative drama; instead, his paintings evoke a mood, a sense of timelessness, and a deep respect for the simple virtues of labor and family life. He aimed to show the beauty and moral worth of his subjects, often highlighting their inner grace rather than their external poverty or toil.

Key Masterpieces of the Rural Genre

The 1820s were a period of intense creativity for Venetsianov, yielding some of his most iconic works.

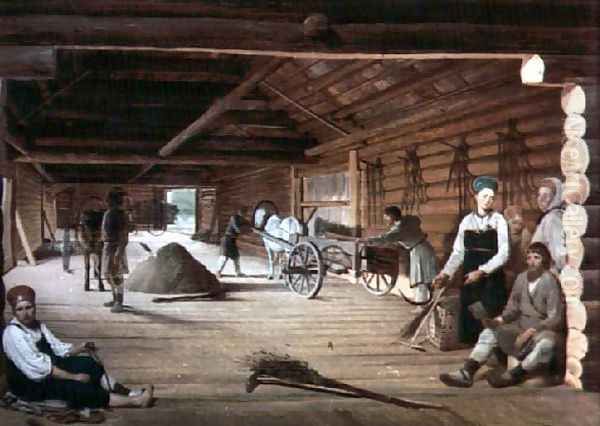

_The Threshing Floor_ (1821-1823, Russian Museum): This large canvas is one of his earliest major genre paintings. It depicts the interior of a barn where peasants are engaged in threshing grain. The composition is complex, with numerous figures, and Venetsianov masterfully handles the perspective and the play of light filtering through the barn's openings. The work was exhibited and well-received, and it's said he sold it for a significant sum (reportedly 5000 rubles), using the money to help establish his art school and even to buy freedom for some of his serf-students.

_Morning of a Landlady_ (c. 1823, Russian Museum): This painting offers a glimpse into the interior of a modest landowner's home. A young woman, presumably the landlady, is shown instructing two peasant girls. The scene is intimate and filled with carefully observed details of domestic life. The soft light entering from the window illuminates the figures and objects, creating a warm, peaceful atmosphere. It showcases Venetsianov's ability to blend genre elements with a portrait-like attention to individual character.

_Spring on Arable Land_ (mid-1820s, Tretyakov Gallery): Perhaps one of his most famous works, this painting epitomizes Venetsianov's poetic vision of peasant life. A peasant woman, dressed in traditional attire, gracefully leads two horses harrowing a field. Her young child sits contentedly on the earth nearby. The vast expanse of the sky and the newly plowed land create a sense of boundless space and the promise of renewal. The figure of the woman is almost iconic, a symbol of motherhood and the life-giving force of nature.

_Reaping. Summer_ (or Harvesting. Summer) (1820s, Tretyakov Gallery): A companion piece in spirit to Spring on Arable Land, this work depicts peasants harvesting grain under a warm summer sky. The figures are shown working in harmony, and the overall mood is one of peaceful labor and abundance. Venetsianov captures the golden light of summer and the rhythmic movements of the reapers.

_Sleeping Shepherd Boy_ (1823-1824, Russian Museum): This charming painting shows a young boy asleep in a field, his flock of sheep grazing nearby. It's a tender depiction of innocence and the tranquility of rural life. The boy's relaxed posture and the peaceful landscape evoke a sense of idyllic calm. The work was highly praised when exhibited.

These works, among others, established Venetsianov as the founder of the peasant genre in Russian painting. He moved beyond mere ethnographic depiction to create images that resonated with a deeper, almost spiritual appreciation for the Russian land and its people. His approach contrasted with the grand historical canvases of contemporaries like Karl Bryullov (1799–1852), whose The Last Day of Pompeii would later take the art world by storm with its dramatic intensity and academic polish. Venetsianov's art was quieter, more introspective, but no less significant in its impact on the development of a national artistic identity.

The Venetsianov School: A Legacy of Teaching

Beyond his own artistic output, Venetsianov made a lasting contribution as an educator. In Safonkovo, he established an art school, attracting numerous pupils, many of whom were from humble backgrounds, including serfs. Venetsianov was known to be a generous teacher, often providing for his students' material needs and even helping to secure their freedom.

His teaching methods were unconventional for the time. He encouraged his students to learn directly from nature, rather than relying solely on copying academic models. This emphasis on direct observation and truthfulness to life was a hallmark of his own art and became a guiding principle for his school. His curriculum was also reportedly broad, including not just drawing and painting, but also subjects like literature and arithmetic, aiming for a well-rounded education.

Among his most talented and notable students were:

Grigory Soroka (1823–1864): Perhaps the most gifted of Venetsianov's pupils, Soroka was a serf whose talent was immense. His landscapes and portraits are characterized by a profound melancholy and a meticulous, almost naive precision. Venetsianov tried to secure his freedom, but tragically, Soroka remained a serf and, after participating in peasant unrest, took his own life. His works, like Fishermen. View of Lake Moldino (1840s), are masterpieces of quiet introspection.

Nikolai Krylov (1802–1831): Known for his winter landscapes, such as Russian Winter (1827), which beautifully captures the atmosphere of a snow-covered village. He died young, but his work showed great promise.

Kapiton Zelentsov (1790–1845): Painted genre scenes and interiors, often with a warmth and attention to detail reminiscent of his master. In the Room. View of the Exchange and the Admiralty from the Window of P. A. Kikin's Apartment is an example.

Alexander Alexeyev (1811–1878): Known for works like Venetsianov's Studio (1827), which provides a valuable visual record of the master's teaching environment.

Lavr Plakhov (1810–1881): A painter and lithographer, he created genre scenes and portraits. Coachmen's Room in the Academy of Arts (1834) is a notable work.

Yevgraf Krendovsky (1810–1870): Ukrainian-born, he studied with Venetsianov and painted genre scenes and portraits, such as Square in a Provincial Town.

Mikhail Scotti (1814–1861): Of Italian descent but born in Russia, he studied with Venetsianov before moving on to Bryullov. He became known for historical paintings and watercolors.

The Venetsianov School played a crucial role in disseminating a new approach to art, one that valued Russian subjects and a more naturalistic style. While the Imperial Academy of Arts remained the dominant institution, Venetsianov and his followers offered an alternative path, laying important groundwork for the later rise of Realism in Russian art. Other landscape painters of the era, like Sylvester Shchedrin (1791–1830), were achieving fame primarily for their Italian landscapes, making Venetsianov's focus on the Russian countryside particularly distinctive.

Caricatures and Social Commentary Revisited

While Venetsianov is primarily remembered for his idyllic peasant scenes, his early interest in caricature and social observation should not be entirely overlooked. His Journal of Caricatures (1808), though short-lived due to censorship, indicates an early inclination towards social commentary. The Napoleonic caricatures, such as The French Crow-Soup and The Nobleman's Reception for Napoleon in Russia, were part of a broader patriotic fervor but also showcased his graphic skill and wit.

After his move to Safonkovo and his immersion in peasant themes, overt social critique largely disappeared from his work. His focus shifted to a more poetic and idealized representation of rural life. However, the very act of choosing peasants as central subjects for serious art, and depicting them with dignity, could be seen as a subtle form of social statement in a society still heavily reliant on serfdom.

Relationship with Contemporaries

Venetsianov's artistic path was somewhat parallel to, rather than directly intersecting with, many of the dominant trends of his time. While he was an Academician, his primary focus on genre scenes of peasant life set him apart from the Academy's emphasis on historical, mythological, and religious subjects, or grand portraiture.

His relationship with Vladimir Borovikovsky was foundational in his early years. With Orest Kiprensky, they were contemporaries, both highly regarded, but Kiprensky's fame rested on his psychologically charged Romantic portraits, while Venetsianov found his niche in genre. Karl Bryullov represented a different artistic pole altogether – his work was international in scope, dramatic, and technically dazzling, appealing to a taste for the grandiose that Venetsianov's quieter art did not cater to.

Vasily Tropinin (1776–1857) was another contemporary who, like Venetsianov, showed an interest in depicting common people and genre scenes, alongside his successful portraiture practice. Tropinin, himself a former serf, brought a particular empathy to his subjects, as seen in works like The Lacemaker. There are affinities between Tropinin's and Venetsianov's interest in everyday Russian life, though their styles and specific focuses differed.

Later Years and Tragic End

Venetsianov continued to paint and teach throughout the 1830s and 1840s. He remained committed to his vision of Russian rural life, though he also undertook some official commissions, including icons for churches and portraits. He sought the title of professor at the Academy of Arts but was not granted it, perhaps because his artistic direction was still considered somewhat outside the academic mainstream.

His life came to a tragic and abrupt end. On December 4 (Old Style) / December 16 (New Style), 1847 (some sources give slightly varying dates like December 17, 1846, but 1847 is most widely accepted), while traveling in the Tver Governorate, the horses pulling his carriage bolted on a steep slope. Venetsianov was thrown from the carriage and killed. He was 67 years old.

Venetsianov's Enduring Place in Russian Art History

Aleksei Venetsianov's legacy is profound and multifaceted. He is rightly considered one of the pioneers of Russian genre painting and a foundational figure in the development of a national school of art. His most significant contributions include:

1. Elevating Peasant Life: He was among the first Russian artists to make the lives of ordinary peasants the central subject of serious, empathetic art, portraying them with dignity and poetic grace.

2. Focus on the Russian Landscape: He turned his gaze to the native Russian countryside, capturing its unassuming beauty and its harmonious relationship with its inhabitants, at a time when many landscape painters sought inspiration in Italy.

3. Emphasis on Naturalism and Light: His dedication to observing nature directly and his skillful rendering of light and atmosphere brought a new level of realism and intimacy to Russian painting.

4. Influence as an Educator: The Venetsianov School nurtured a generation of artists who continued to explore Russian themes and develop a more naturalistic approach to art. His students carried his influence forward.

While his idealized vision of peasant life would later be challenged by the more critical Realism of the Peredvizhniki (The Wanderers), such as Ivan Kramskoi (1837–1887), Ilya Repin (1844–1930), and Alexei Savrasov (1830–1897, whose The Rooks Have Arrived echoes Venetsianov's love for the Russian landscape), Venetsianov's work laid essential groundwork. The Peredvizhniki, in their commitment to depicting Russian life in all its facets, owed a debt to his pioneering efforts to legitimize such subjects.

Venetsianov's art offered a gentle, humane vision of Russia, one rooted in the soil and the simple virtues of its people. He found beauty and poetry where many had previously seen only the mundane or the picturesque. His paintings remain beloved for their sincerity, their warmth, and their timeless depiction of a world where humanity and nature exist in quiet harmony. He was, in essence, one of the first truly "Russian" painters in terms of his subject matter and sensibility, paving the way for future generations to explore the rich tapestry of Russian life and identity. His contemporary, the great poet Alexander Pushkin (1799-1837), was forging a national literature in the Russian language; Venetsianov, in parallel, was helping to forge a national art.

Conclusion

Aleksei Gavrilovich Venetsianov was more than just a painter of charming rural scenes. He was an innovator who dared to look at his own country and its people with fresh eyes, finding artistic inspiration not in the classical past or foreign lands, but in the fields and cottages of provincial Russia. His dedication to depicting the everyday life of the peasantry with warmth and dignity, his mastery of light and atmosphere, and his influential role as a teacher secure his place as a cornerstone of Russian art. His legacy endures in the quiet beauty of his canvases and in the artistic traditions he helped to establish, making him a figure of enduring importance and affection in the annals of art history.