Nikolai Petrovich Bogdanov-Belsky stands as a significant figure in the landscape of Russian art, bridging the late 19th and early 20th centuries. A master of genre painting and portraiture, he dedicated his artistic life primarily to capturing the essence of Russian peasant life, with a particular and enduring focus on the world of rural children and their education. Associated with the influential Peredvizhniki (Wanderers) movement, Bogdanov-Belsky combined meticulous realism with profound empathy, creating works that resonated deeply with his contemporaries and continue to offer valuable insights into a pivotal era of Russian history. His canvases serve not only as aesthetic objects but as historical documents, reflecting the social fabric, aspirations, and challenges of the Russian countryside.

Humble Origins and Early Promise

Nikolai Petrovich Bogdanov was born on December 6, 1868, in the village of Shitiki, located in the Belsky district of the Smolensk Governorate, Russian Empire. His origins were exceptionally modest; he was the illegitimate son of a poor peasant woman, a farm laborer. His early life was marked by the hardships typical of rural poverty in post-emancipation Russia. However, even amidst these challenging circumstances, his innate talent for drawing became apparent at a young age.

Fortunately, his artistic inclinations did not go unnoticed. Semyon Rachinsky, a professor at Moscow State University who had renounced his academic career to establish a school for peasant children in his native village of Tatevo, recognized the boy's potential. Rachinsky played a pivotal role in Bogdanov's early development, providing him with initial guidance and fostering his interest in art. Another crucial figure was a local priest who, impressed by the boy's abilities, helped facilitate his entry into an icon-painting workshop at the renowned Trinity Lavra of St. Sergius, a spiritual and artistic center near Moscow.

This early training in icon painting provided Bogdanov with a solid foundation in draughtsmanship and the traditional techniques of Russian religious art. While he would later move towards secular realism, the discipline and precision learned during this period likely informed his later meticulous style. The experience exposed him to the rich artistic heritage of Russia and honed the skills necessary for a future career in painting.

Academic Training and Artistic Formation

Recognizing that Bogdanov's talent warranted more formal training, Rachinsky arranged for him to study at the prestigious Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture from 1884 to 1889. Here, he studied under prominent artists such as Vasily Polenov, Illarion Pryanishnikov, and Vladimir Makovsky. These teachers were themselves significant figures in the Russian realist tradition, and their influence helped shape Bogdanov-Belsky's commitment to depicting everyday life with accuracy and sensitivity. Makovsky, in particular, was known for his genre scenes portraying urban and rural life, offering a direct model for Bogdanov's future thematic interests.

Following his studies in Moscow, Bogdanov-Belsky furthered his education at the Imperial Academy of Arts in Saint Petersburg from 1894 to 1895. This was the pinnacle of artistic education in the Russian Empire. Crucially, he entered the studio of the towering figure of Russian realism, Ilya Repin. Studying under Repin was a formative experience, exposing Bogdanov-Belsky to the highest standards of psychological portraiture and large-scale historical and social commentary painting. Repin's emphasis on capturing the inner life of his subjects and his commitment to socially relevant art profoundly impacted the younger artist.

During the late 1890s, Bogdanov-Belsky also traveled abroad, visiting artistic centers in Paris and Munich. He worked in private studios, absorbing the influences of contemporary European art, including aspects of Impressionism, particularly its attention to light and atmosphere. However, while he incorporated a brighter palette and looser brushwork at times, he remained fundamentally committed to the narrative clarity and social focus characteristic of Russian realism.

The Peredvizhniki and Realist Ideals

In 1895, Bogdanov-Belsky became a member of the Society for Travelling Art Exhibitions, better known as the Peredvizhniki (the Wanderers or Itinerants). This group, founded decades earlier by artists like Ivan Kramskoi and Vasily Perov, was arguably the most important artistic movement in late 19th-century Russia. The Peredvizhniki rejected the Neoclassical constraints and mythological themes favored by the Imperial Academy, advocating instead for a realist art that depicted the lives of ordinary Russians, addressed social issues, and was accessible to a wider public through traveling exhibitions across the provinces.

Bogdanov-Belsky's artistic concerns aligned perfectly with the Peredvizhniki ethos. His focus on peasant life, his sympathetic portrayal of children, and his exploration of themes like poverty and education resonated with the movement's core principles. He became an active participant, exhibiting regularly with the group. His works contributed significantly to the Peredvizhniki's ongoing project of creating a national art rooted in the realities of Russian life. Other prominent members whose work shared thematic or stylistic ground included landscape masters like Alexei Savrasov and Ivan Shishkin, and painters of historical or social scenes like Vasily Surikov.

While a committed member, some accounts suggest Bogdanov-Belsky possessed an independent streak, occasionally chafing against organizational aspects, leading to the affectionate or perhaps slightly critical nickname "the wanderer" within the Wanderers, highlighting a certain individuality even within the collective movement. His dedication to the group's ideals, however, remained steadfast throughout its active period.

Focus on Education: The Rachinsky School Paintings

Among Bogdanov-Belsky's most celebrated and enduring works are those depicting peasant children engaged in learning, particularly scenes set in the school established by his mentor, Semyon Rachinsky. These paintings are more than simple genre scenes; they are powerful statements about the potential of the rural populace and the transformative power of education in a society grappling with modernization and social change.

The most famous of these is undoubtedly Mental Arithmetic. In the Public School of S. A. Rachinsky (also known widely as Oral Calculation or At the Blackboard), painted in 1895. This iconic work shows a group of peasant boys intently focused on a complex arithmetic problem chalked on a blackboard, presumably posed by Rachinsky himself, who is depicted observing them. The painting captures the intense concentration, the furrowed brows, and the collaborative effort of the students. It masterfully conveys the intellectual spark ignited in these children, challenging prevailing stereotypes about the peasantry. The work became immensely popular, widely reproduced, and seen as an optimistic symbol of Russia's future.

Another significant work in this vein is At the Door of the School (1897). This painting, believed to have autobiographical undertones, depicts a poorly dressed boy hesitating at the threshold of a classroom, perhaps representing the artist's own tentative steps towards education. It speaks volumes about the barriers – both material and psychological – faced by peasant children seeking knowledge, while also hinting at the hope that lies beyond the door.

Beginners (1897) similarly explores the theme of early education, portraying younger children perhaps in their first encounters with literacy or numeracy. Through these works, Bogdanov-Belsky not only paid homage to his benefactor Rachinsky but also championed the cause of universal education, highlighting the intelligence and eagerness to learn found among the often-overlooked rural youth. His detailed realism, combined with a warm, empathetic portrayal of the children, makes these paintings particularly moving and effective.

Depictions of Peasant Life and Rural Scenes

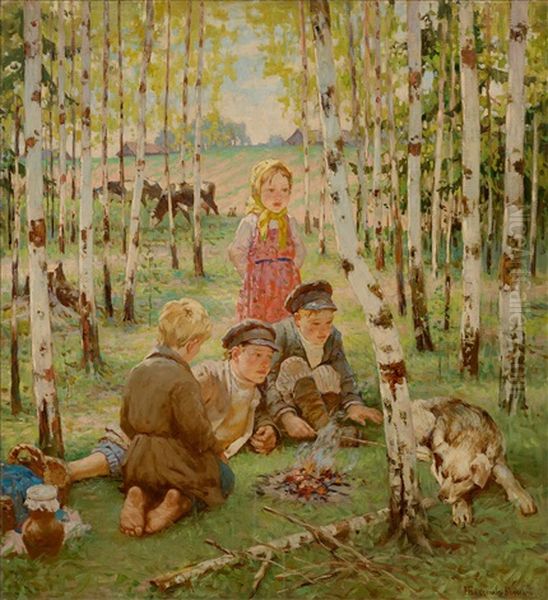

Beyond the classroom, Bogdanov-Belsky dedicated much of his oeuvre to capturing the broader spectrum of peasant life. He painted scenes of everyday labor, moments of leisure, family gatherings, and the simple, often harsh, realities of the Russian countryside. His deep familiarity with this world, stemming from his own upbringing, allowed him to portray his subjects with authenticity and dignity, avoiding condescension or romanticization.

New Tale (or New Fairy Tale), painted in 1891 during his earlier career, shows children gathered around an adult figure, perhaps listening intently to a story. It highlights the importance of oral tradition and shared moments in village life, while also subtly hinting at the children's curiosity and imagination. The setting, though humble, is rendered with care, and the figures are imbued with individual character.

The New Masters (1913) reflects the changing social dynamics in the countryside in the years leading up to the Revolution. It depicts a scene where former peasants, having acquired wealth, are perhaps inspecting or taking possession of a former landowner's estate. The painting captures a sense of transition and the shifting power structures within rural Russia, a theme explored by other artists concerned with social change.

His works often captured moments of quiet contemplation or simple pleasure amidst the demanding rural existence. Mid-day Fishing portrays children enjoying a moment of leisure, connecting with nature. Morning in the Village (1903) evokes the atmosphere of the countryside at the start of the day. These paintings demonstrate his skill in rendering landscapes and integrating figures naturally within their environment, akin perhaps to the atmospheric landscapes of Isaac Levitan, though Bogdanov-Belsky's primary focus usually remained on the human element. His use of warm light and careful attention to detail imbues these scenes with a sense of peace and timelessness.

Portraits and Children

Bogdanov-Belsky was also a highly accomplished portraitist. While he painted commissioned portraits of notable figures, his most compelling work in this genre often involved the same subjects who populated his genre scenes: peasants, and especially children. He possessed a remarkable ability to capture the individuality and inner life of his sitters, particularly the innocence, curiosity, and sometimes premature gravity of peasant children.

His painting simply titled Children (1910) is a fine example, showcasing his sensitive handling of young subjects. He avoided sentimentality, instead presenting the children with directness and respect. Their expressions are often thoughtful, suggesting an awareness beyond their years, shaped by their environment. Children at the Piano explores a different setting, perhaps suggesting access to culture and refinement, but still focuses on the universal theme of childhood engagement and discovery.

His approach to portraiture shared the realist commitment to psychological depth seen in the work of his teacher Repin and contemporaries like Valentin Serov, another master portraitist of the era. However, Bogdanov-Belsky's consistent return to rural subjects gave his portraiture a distinct character, documenting the faces of a Russia often unseen in the salons of the elite. He saw dignity and beauty in the weathered faces of elderly peasants and the bright, hopeful eyes of their grandchildren.

Recognition, Later Life, and Emigration

Bogdanov-Belsky's talent and dedication earned him significant recognition within the Russian art world. In 1903, he was granted the title of Academician by the Imperial Academy of Arts, a prestigious honor signifying his established position. It was around this time, with the approval of Tsar Nicholas II, that he formally adopted the double-barreled surname "Bogdanov-Belsky," combining his patronymic-derived name with a toponymic reference to his native Belsky district, thus acknowledging both his lineage and his roots.

He became an influential figure in several artistic organizations. From 1913 to 1918, he served as the chairman of the Kuindzhi Society, an important association of artists founded in honor of the landscape painter Arkhip Kuindzhi. This role underscored his standing among his peers and his commitment to supporting fellow artists. He maintained connections with other leading figures, such as the Impressionist-influenced painter Konstantin Korovin, whom he visited and worked alongside.

The Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 and the subsequent Civil War dramatically altered the landscape of Russian society and art. Like many artists associated with the pre-revolutionary realist tradition, Bogdanov-Belsky found the new cultural climate challenging. While his depictions of peasant life might seem aligned with Soviet ideals, his style and perhaps his personal inclinations were rooted in the older order. In 1921, he emigrated from Russia, settling in Riga, the capital of newly independent Latvia.

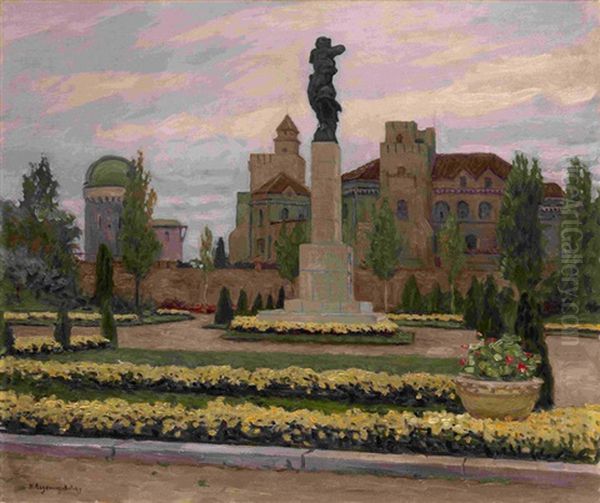

He continued to paint actively in Riga for two decades, focusing primarily on portraits and genre scenes, often drawing on nostalgic memories of pre-revolutionary Russia. His work remained popular, and he exhibited internationally, including a significant showing of over ten works in the United States in 1924. A later work like Cityscape (1930s), depicting a view possibly from his time in Montenegro, shows his continued engagement with landscape and place, even in exile. The rise of Soviet power and the outbreak of World War II forced him to move again. He died in Berlin on February 19, 1945, amidst the final chaotic months of the war.

Artistic Network and Influence

Throughout his career, Bogdanov-Belsky was part of a rich network of Russian artists. His training placed him under the direct influence of Vasily Polenov, Vladimir Makovsky, and most importantly, Ilya Repin. His membership in the Peredvizhniki connected him closely with Ivan Kramskoi, Vasily Perov, Alexei Savrasov, Ivan Shishkin, Vasily Surikov, and Viktor Vasnetsov. His leadership role in the Kuindzhi Society linked him to the legacy of Arkhip Kuindzhi and his followers. His interactions with contemporaries like Konstantin Korovin, Isaac Levitan, Valentin Serov, Vasily Polenov, and Mikhail Nesterov situated him within the vibrant and diverse St. Petersburg and Moscow art scenes.

While Bogdanov-Belsky did not found a distinct school or movement, his influence can be seen in the continuation of the realist tradition and particularly in the sympathetic portrayal of rural life and childhood. His focus on education provided a powerful visual argument for social progress that resonated widely. His work stands as a testament to the enduring power of realism to convey social commentary and human emotion. Although later overshadowed by the radical experiments of the Russian avant-garde (figures like Kazimir Malevich or Wassily Kandinsky) and the subsequent imposition of Socialist Realism, Bogdanov-Belsky's art retained its appeal for its technical skill, narrative clarity, and heartfelt humanism.

Legacy and Conclusion

Nikolai Bogdanov-Belsky occupies a cherished place in the history of Russian art. He was a master craftsman whose technical proficiency served a deeply humanistic vision. His paintings offer an invaluable window into the world of the Russian peasantry during a period of profound social and political transformation. He captured the hardships, the simple joys, the communal bonds, and the burgeoning aspirations of rural life with unparalleled empathy and authenticity.

His depictions of children, especially those centered around Rachinsky's school, remain his most iconic contribution. These works transcend mere genre painting, becoming powerful symbols of hope, potential, and the importance of education in unlocking human capabilities. Paintings like Mental Arithmetic have achieved the status of cultural touchstones in Russia, beloved for their warmth, optimism, and celebration of intellectual curiosity in unexpected settings.

Today, Bogdanov-Belsky's works are held in major collections, including the State Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow and the State Russian Museum in Saint Petersburg, as well as numerous regional museums in Russia and collections abroad. His enduring legacy lies in his ability to connect viewers across time to the lives of ordinary people, rendered with dignity, respect, and consummate artistic skill. He remains a chronicler of a lost world, whose images continue to speak of the enduring human spirit found in the fields, villages, and classrooms of late Imperial Russia.