Filipp Andreevich Malyavin stands as one of the most distinctive and powerful figures in Russian art at the turn of the 20th century. Born into the vast rural landscape he would later immortalize on canvas, Malyavin developed a unique artistic language characterized by explosive color, dynamic energy, and an empathetic focus on the Russian peasantry, particularly its women. His life journey, from humble beginnings and monastic training to the heights of international acclaim and the hardships of emigration and war, mirrors the turbulent history of his homeland. Malyavin’s art remains a vibrant testament to the enduring spirit of the Russian people, rendered with a technical bravura and emotional intensity that continues to captivate audiences today. His work bridges the gap between the 19th-century Realism of his teachers and the burgeoning modernism of the early 20th century, creating a style uniquely his own.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Filipp Malyavin was born on October 22, 1869, in the village of Kazanka in the Samara Governorate of the Russian Empire, into a large peasant family. From a young age, he displayed an undeniable talent and passion for drawing, sketching the world around him with an innate understanding of form and life. His rural upbringing immersed him in the culture, traditions, and visual richness of Russian village life, themes that would become central to his artistic identity. This deep connection to his roots provided an inexhaustible source of inspiration throughout his career.

Seeking an outlet for his artistic inclinations, the young Malyavin traveled to Greece, hoping to study icon painting at the famed St. Panteleimon Monastery on Mount Athos. Between 1885 and 1891, he served as a lay brother and learned the techniques of religious art. While the experience provided him with foundational skills in painting, the rigid canons of icon painting ultimately proved too restrictive for his burgeoning, expressive talent. He found the work, often involving the copying of established patterns, stifling to his creative spirit. This period, however, likely honed his discipline and understanding of color composition, albeit within a very different aesthetic framework than the one he would later embrace.

The Saint Petersburg Academy and the Influence of Repin

Malyavin's trajectory changed dramatically in 1891 when the sculptor Vladimir Beklemishev visited Mount Athos. Recognizing the young man's exceptional talent, Beklemishev was impressed by Malyavin's drawings and encouraged him to pursue formal art education in the Russian capital. With Beklemishev's support, Malyavin traveled to Saint Petersburg in 1892 and successfully gained admission to the prestigious Imperial Academy of Arts, a significant achievement for someone of his peasant background.

At the Academy, Malyavin entered the studio of the renowned master Ilya Repin, a leading figure of the Russian Realist movement known as the Peredvizhniki (Wanderers). Studying under Repin from 1892 until his graduation in 1899 was a formative experience. Repin's workshop was a dynamic environment, and while Repin himself was a master of psychological portraiture and large-scale historical scenes, such as the famous Barge Haulers on the Volga, he encouraged his students to develop their individual styles. Malyavin absorbed the technical mastery and psychological depth emphasized by Repin but soon began to diverge from his teacher's more traditional Realism.

During his time at the Academy, Malyavin began to gravitate towards the subjects he knew best: the peasants of rural Russia. His approach, however, was markedly different from the often somber or socially critical depictions favored by many earlier Peredvizhniki artists like Vasily Perov or Ivan Kramskoi. Malyavin sought to capture the vitality, energy, and raw spirit of his subjects, employing increasingly bold techniques and vibrant colors.

Emergence of a Unique Style

While studying under Repin, Malyavin started forging a path distinct from academic conventions and even from the mainstream Realism of his mentor. He began experimenting with broader brushstrokes, more intense color palettes, and compositions that emphasized movement and emotion over precise anatomical rendering or narrative clarity. His focus shifted decisively towards the depiction of peasant life, not as a subject for social commentary, but as a source of immense visual power and national identity.

His developing style showed an affinity with contemporary European artistic trends, though filtered through a distinctly Russian sensibility. There are echoes of Impressionism in his attention to light and color, perhaps influenced by French masters like Claude Monet or Auguste Renoir, whose works were becoming known in Russia. More significantly, his bold application of paint and expressive freedom align with Post-Impressionist sensibilities, reminiscent of the emotional intensity found in Vincent van Gogh or the decorative color fields of Paul Gauguin, although direct influence is debated.

A key acknowledged influence was the Swedish painter Anders Zorn, known for his virtuoso brushwork and vibrant depictions of peasant life and society portraits. Malyavin admired Zorn's fluid technique and ability to capture momentary effects of light and movement. Malyavin also absorbed elements of Art Nouveau, visible in the swirling, decorative patterns of fabrics and the rhythmic lines that often define his figures. He synthesized these diverse influences into a powerful, personal idiom where color, particularly shades of red, became a primary vehicle for expression, symbolizing life, passion, and the untamed spirit of rural Russia.

Breakthrough and Recognition: 'Laughter' and 'Whirlwind'

Malyavin’s graduation work from the Academy in 1899, initially titled Peasant Woman Laughing but now widely known as Laughter (Smekh), marked his explosive arrival on the Russian art scene. The large canvas depicts peasant women, clad in brilliantly colored traditional dresses, overcome with joyous, unrestrained laughter against a simple green background. The painting’s sheer exuberance, the dazzling intensity of the reds, and the broad, almost aggressive brushwork were radical for their time.

The painting caused a sensation and significant controversy. The Council of the Imperial Academy of Arts, finding its style too bold and perhaps its subject matter lacking the expected decorum or narrative weight, refused to grant Malyavin the title of artist for it. This rejection highlighted the clash between Malyavin's innovative vision and the conservative tastes still prevalent in academic circles.

Despite the initial setback at home, Laughter achieved international triumph. Exhibited at the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1900, the painting was awarded a gold medal, bringing Malyavin widespread recognition. Its success was a vindication of his artistic direction. The work was subsequently acquired by the Italian government for the Galleria Internazionale d'Arte Moderna in Venice, cementing his reputation abroad. Laughter became an iconic image, embodying a new, dynamic representation of Russian national character.

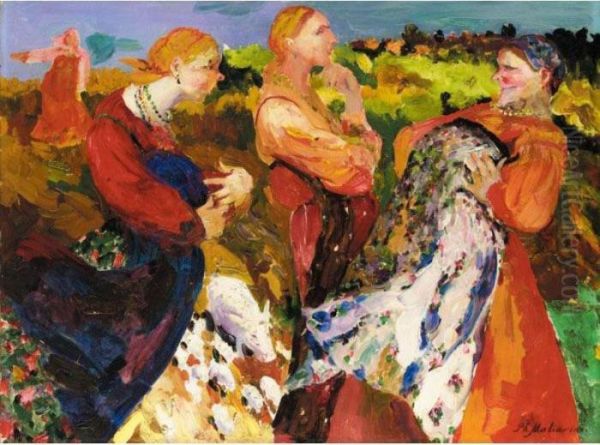

Following this success, Malyavin produced another masterpiece, Whirlwind (Vikhr), completed in 1906. This monumental canvas depicts a group of peasant women caught in a swirling, ecstatic dance. The figures seem to merge with the vibrant, almost abstract patterns of their dresses, creating an overwhelming impression of movement, energy, and collective emotion. The painting is a tour-de-force of color and dynamic composition, often considered the pinnacle of his exploration of peasant themes. Like Laughter, Whirlwind showcases Malyavin's unique ability to translate the raw energy of folk life into powerful visual art. Early support also came from the discerning collector Pavel Tretyakov, founder of the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow, who acquired some of Malyavin's student works, recognizing his potential early on.

The Peasant Women of Malyavin

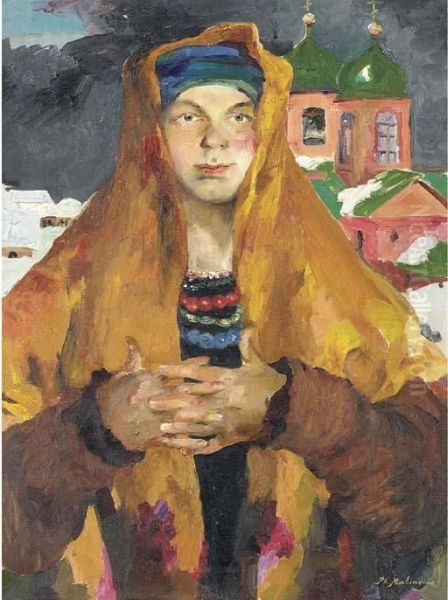

The central and most enduring theme in Filipp Malyavin's oeuvre is the Russian peasant woman, often referred to collectively in Russian as 'Baby'. He returned to this subject throughout his career, depicting women singly or in groups, laughing, dancing, working, or simply standing with monumental presence. His portrayal diverged sharply from the sentimentalized or purely ethnographic representations common in earlier Russian art. Malyavin saw in these women not victims of hardship, but embodiments of elemental strength, vitality, and the untamed spirit of Russia itself.

His peasant women are almost always depicted in brightly colored traditional costumes, particularly featuring dazzling shades of red – scarlet, crimson, vermillion. Red, in Russian folk culture, carries connotations of beauty, celebration, and life force, and Malyavin employed it with unparalleled intensity. The fabrics swirl around the figures, often rendered with thick, energetic brushstrokes that emphasize texture and movement, sometimes dissolving into near-abstract patterns. This focus on color and decorative effect connects his work to modernist trends, yet the emotional core remains deeply rooted in Russian identity.

Compared to his contemporary Abram Arkhipov, who also famously painted peasant women in vibrant red attire, Malyavin's approach is generally more dynamic and less focused on individual psychology. While Arkhipov’s women often possess a quiet dignity or gentle melancholy, Malyavin’s figures are frequently caught in moments of high emotion – ecstatic laughter, frenzied dance, or stoic resilience. They possess a raw, almost primal energy. His canvases celebrate their physical robustness and inner power, presenting them as archetypes of national vitality rather than specific individuals burdened by social circumstance.

Portraiture and Other Subjects

While Filipp Malyavin is most renowned for his vibrant depictions of peasant women, his artistic output also included significant work in portraiture. He applied his characteristic energetic brushwork and keen psychological insight to capture the likenesses and personalities of various sitters, ranging from fellow artists and intellectuals to members of his own family and prominent figures of the era. His portrait style often retained the dynamism of his peasant scenes, focusing on capturing the sitter's inner vitality rather than achieving photographic realism.

Among his notable portraits are those of his family members, which often possess a particular warmth and intimacy. He also painted figures from the Russian cultural elite. There are accounts, though sometimes debated in terms of formal commission versus sketches, that Malyavin painted or drew Vladimir Lenin after the Revolution. If true, this interaction highlights the complex position Malyavin occupied during a period of immense political upheaval. He is also known to have painted portraits of the writer Maxim Gorky and the celebrated opera singer Feodor Chaliapin, capturing the powerful presence of these iconic figures.

These portraits demonstrate Malyavin's versatility as an artist. Even when working within the more conventional genre of portraiture, his distinctive style – the bold strokes, the rich color, the sense of immediacy – remained evident. He approached his sitters with the same intensity and search for essential character that defined his peasant studies, proving his ability to adapt his unique vision to different subjects.

Association with 'Mir Iskusstva'

Filipp Malyavin's career coincided with the flourishing of the Mir Iskusstva (World of Art) movement, a highly influential group of Russian artists, writers, and designers active roughly from the late 1890s through the first decade of the 20th century. Led by figures like the impresario Sergei Diaghilev and artists Alexandre Benois and Léon Bakst, Mir Iskusstva championed aestheticism, artistic individualism, and a synthesis of arts. They looked to the past, particularly the 18th century, and to European Symbolism and Art Nouveau, often favoring refined, stylized, and sometimes theatrical or fantastical subjects. Other key members included Konstantin Somov, Mstislav Dobuzhinsky, and Nicholas Roerich.

Malyavin exhibited with the Mir Iskusstva group, and his work shared certain characteristics with their aesthetic, such as a strong emphasis on color, decorative qualities, and a departure from the civic-minded Realism of the Peredvizhniki. His bold technique and modern sensibility aligned with their goal of revitalizing Russian art. However, Malyavin's focus on raw peasant energy and his often rough, expressive brushwork set him apart from the more typically elegant and sophisticated style of core Mir Iskusstva members like Benois or Somov.

While artists like Léon Bakst achieved fame for their exotic and sensual designs for Diaghilev's Ballets Russes, Malyavin remained grounded in the depiction of Russian rural life. His connection to Mir Iskusstva was perhaps more one of shared exhibition platforms and a common desire to break from academic constraints than a deep stylistic or ideological alignment. His art possessed a visceral earthiness that contrasted with the often refined, nostalgic, or symbolist tendencies of many World of Art painters. He was a fellow traveler, respected for his unique power, rather than a central figure within the movement's dominant aesthetic. His contemporary Valentin Serov, another artist associated with both Repin's circle and Mir Iskusstva, navigated these currents differently, achieving renown for his psychologically astute society portraits.

Navigating Revolution and Change

The Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 and the subsequent establishment of the Soviet state profoundly altered the cultural landscape in Russia, presenting both opportunities and challenges for artists like Malyavin. In the immediate post-revolutionary years, there was a period of relative artistic freedom and experimentation. It was during this time that Malyavin reportedly created portraits or sketches of Vladimir Lenin, possibly facilitated by Anatoly Lunacharsky, the first Soviet People's Commissar for Education, who initially oversaw cultural affairs with a degree of tolerance for diverse styles.

However, the cultural climate gradually shifted. The rise of movements like Proletkult emphasized art that directly served the ideological needs of the new proletarian state. While Malyavin's peasant subjects might seem aligned with the revolution's focus on the common people, his style – increasingly seen as individualistic, expressive, and lacking clear narrative or didactic purpose – began to fall out of favor with influential critics. His vibrant, sometimes chaotic canvases did not fit the emerging demands for clarity, optimism, and heroic realism that would eventually coalesce into the doctrine of Socialist Realism.

By the early 1920s, Malyavin's work was increasingly criticized as "decadent" or belonging to the bourgeois past. His focus on the "elemental," sometimes wild, spirit of the peasantry was viewed with suspicion, contrasting sharply with the idealized, industrious peasants and workers favored by emerging Soviet artists like Isaak Brodsky, known for his detailed depictions of revolutionary leaders, or later figures like Alexander Gerasimov. The artistic environment became increasingly restrictive, prioritizing overtly political and propagandistic art. This changing atmosphere likely contributed to Malyavin's decision to leave Russia.

Emigration and Life Abroad

Feeling increasingly alienated by the changing artistic and political climate in Soviet Russia, Filipp Malyavin emigrated in 1922. He initially traveled through Riga and Berlin before settling in Paris, which was then a major center for Russian émigré culture. He established a studio there and continued to paint, primarily focusing on portraits and nostalgic depictions of Russian peasant life, themes that resonated with the émigré community and international collectors interested in Russian art.

He held successful exhibitions in Paris and other European cities, maintaining a degree of international recognition. His distinctive style, though perhaps less groundbreaking than in his earlier years, remained powerful and recognizable. He adapted somewhat to his new environment but never fully abandoned the subjects and artistic language forged in Russia. His work from this period often carries a sense of longing or reflection on the world he had left behind.

Later, Malyavin moved to Nice on the French Riviera, attracted by the light and perhaps seeking a quieter life. He continued to work, producing portraits of fellow émigrés and society figures, as well as variations on his famous peasant themes. While living abroad, he existed alongside other prominent Russian émigré artists like Marc Chagall and Wassily Kandinsky, although their artistic paths and styles were vastly different from his own. Malyavin remained somewhat unique, a powerful exponent of a specifically Russian national modernism, even in exile. His life abroad allowed him to continue his artistic practice free from the ideological constraints imposed in the Soviet Union, but it also separated him from the native soil that had been his primary inspiration.

The Final Years: War and Tragedy

The outbreak of World War II cast a dark shadow over Malyavin's later years. In 1940, while visiting Brussels, Belgium, the city was occupied by Nazi Germany. Malyavin, an elderly Russian émigré, fell under suspicion. He was arrested by the occupying forces, accused of being a spy. He endured interrogations and faced the terrifying prospect of execution.

Although he eventually managed to convince his captors of his innocence and was released, the ordeal left him deeply traumatized and physically weakened. Faced with the dangers and difficulties of wartime travel, the aging artist undertook an arduous journey on foot, attempting to walk from Brussels back to his home in Nice in the south of France.

This grueling trek proved too much for his frail health. Exhausted and broken by the experience, Filipp Malyavin reached Nice but died shortly thereafter, on December 23, 1940. His death marked a tragic end to a life dedicated to art, a life that had begun in rural poverty, soared to international fame, and ultimately succumbed to the brutalities of war and displacement. The vibrant energy that characterized his canvases stood in stark contrast to the somber circumstances of his final days.

Legacy and Influence

Filipp Malyavin left behind a powerful and unique legacy in the history of Russian art. He stands as a pivotal figure who bridged the 19th-century Realist tradition, embodied by his teacher Ilya Repin, and the modernist explorations of the early 20th century. His most significant contribution lies in his revolutionary depictions of Russian peasant life, particularly women, whom he portrayed with unprecedented dynamism, color, and emotional force. Works like Laughter and Whirlwind remain iconic images of Russian art, celebrated for their technical brilliance and their capture of an elemental national spirit.

His bold use of color, especially his signature vibrant reds, and his energetic, often thick brushwork pushed the boundaries of painting in Russia at the time. While associated with the Mir Iskusstva circle, his style retained a raw, expressive quality that set him apart. He synthesized influences from European modernism, such as the work of Anders Zorn, with deeply Russian themes and folk aesthetics, creating a highly personal artistic language. His work can be seen in dialogue with other distinctive Russian modernists like Mikhail Vrubel, known for his Symbolist intensity, or Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin with his unique spatial constructions and color theories, though Malyavin's focus remained more grounded in the human figure and folk traditions.

Although his emigration in 1922 and the subsequent dominance of Socialist Realism in the Soviet Union limited his direct influence on later generations of artists within Russia for a time, his work has always been highly regarded and is prominently featured in major collections, including the State Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow and the State Russian Museum in Saint Petersburg. Internationally, his paintings continue to command attention at auctions and are recognized for their artistic power and historical significance. Malyavin's enduring legacy rests on his ability to convey the vibrant soul of rural Russia through a visually stunning and emotionally resonant art.

Conclusion

Filipp Andreevich Malyavin remains a towering figure in Russian art, an artist whose life and work were deeply intertwined with the dramatic transformations of his era. From his peasant roots and monastic beginnings to the studios of the Imperial Academy and the salons of Paris, he forged a unique artistic path. His canvases, pulsating with color and energy, offered a new vision of the Russian peasantry, celebrating its vitality and strength with unprecedented boldness. Though his later years were marked by emigration and tragedy, the power of his artistic achievement endures. Malyavin's legacy is that of a master colorist and a profound interpreter of the Russian spirit, whose vibrant depictions of life continue to resonate with undiminished force.