Alexandre Cabanel stands as a towering figure in the landscape of 19th-century French art. A quintessential representative of the Academic tradition, his career spanned a period of immense artistic change and upheaval. Celebrated in his time for his technical mastery, elegant compositions, and idealized subjects drawn from history, mythology, and religion, Cabanel enjoyed immense success, official recognition, and the patronage of the highest echelons of society, including Emperor Napoleon III. Yet, his staunch adherence to established artistic conventions placed him in direct opposition to the burgeoning avant-garde movements, particularly Impressionism, making him a figure of both admiration and controversy. Understanding Cabanel is crucial to grasping the complexities of the 19th-century art world, the power of the French Academy, and the enduring appeal of classical beauty.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

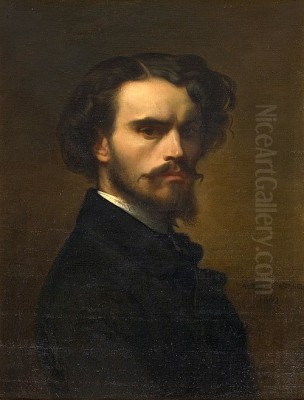

Born on September 28, 1823, in Montpellier, a sun-drenched city in the Hérault region of southern France, Alexandre Cabanel displayed artistic inclinations from a young age. His precocious talent did not go unnoticed, and local support enabled him to pursue formal training. At the tender age of seventeen, he made the pivotal move to Paris, the undisputed center of the European art world, to enroll at the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts. This institution was the bastion of French artistic tradition, shaping generations of painters and sculptors according to rigorous classical principles.

At the École, Cabanel entered the studio of François-Édouard Picot (1786-1868), a respected history painter and portraitist who himself had been a student of Jacques-Louis David's protégé, François-André Vincent. Picot instilled in his students the core tenets of Academic painting: the primacy of drawing, the importance of historical and mythological subjects (the grande manière), compositional clarity based on classical and Renaissance models, and a highly finished, polished execution that concealed the artist's brushwork. This rigorous training provided Cabanel with the technical foundation and aesthetic principles that would define his entire career.

The Prix de Rome and Italian Sojourn

A crucial stepping stone for ambitious young artists within the Academic system was the Prix de Rome, a fiercely competitive scholarship awarded by the Académie des Beaux-Arts that allowed winners to study at the French Academy in Rome, located in the Villa Medici. In 1845, Cabanel achieved this distinction, winning the Second Grand Prix in painting. Although not the First Prize, it secured him the coveted opportunity to spend several years immersed in the artistic treasures of Italy.

His time in Rome, lasting approximately five years, was profoundly influential. He studied firsthand the masterpieces of the Italian Renaissance, particularly the works of Raphael and Michelangelo, and absorbed the lessons of classical antiquity. This immersion deepened his commitment to idealized forms, harmonious compositions, and elevated subject matter. It was during this period that he began to forge his mature style, blending the precision learned under Picot with the grandeur and grace of the Italian masters. He also formed important connections, including a lasting friendship with Alfred Bruyas, a fellow Montpellier native, art collector, and patron who would commission several works from him, including Albaydé (1848). He also encountered other artists, like the Neapolitan painter Domenico Morelli, fostering connections within the international artistic community residing in Rome.

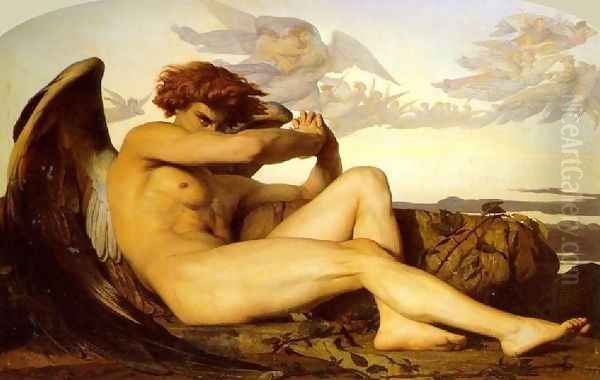

Several significant early works date from this Italian period, demonstrating his developing skills and ambition. His Orestes (1846), depicting the tormented Greek hero, showcased his ability to handle complex historical themes, though its realism and depiction of the nude reportedly drew some criticism back in Paris, hinting at an early willingness to push boundaries within acceptable limits. More famously, his first version of The Fallen Angel (1847), painted while at the Villa Medici, remains one of his most compelling early creations. Depicting Lucifer moments after his expulsion from Heaven, the work combines classical anatomy with a palpable sense of Romantic anguish and defiance, a powerful image that resonated deeply. He also tackled major religious themes, such as The Death of Moses (1851), a work that demonstrated his capacity for large-scale historical compositions demanded by the Academy.

Ascendancy in the Second Empire: Salon Success

Upon his return to Paris in the early 1850s, Cabanel set about establishing his reputation through the primary venue for artistic recognition: the official Paris Salon. Organized by the Académie des Beaux-Arts, the Salon was an annual (later biennial) exhibition that could make or break an artist's career. Cabanel quickly proved adept at navigating this system. His paintings, characterized by their technical polish, elegant figures, and appealing subject matter, found favor with the Salon juries and the public.

He received numerous medals and accolades throughout the 1850s, steadily building his stature. His subjects often drew from mythology, religion, and literature, rendered with a smooth, idealized finish that appealed to prevailing tastes. He excelled at depicting the human form, particularly the female nude, which he presented with a refined sensuality that stopped short of offending official morality, unlike the more challenging realism of contemporaries like Gustave Courbet.

The pivotal moment in Cabanel's rise to fame occurred at the Salon of 1863 with his painting The Birth of Venus. This large canvas depicts the goddess of love reclining languidly on the waves, attended by playful putti. The work was an immediate sensation. Its smooth, pearlescent rendering of Venus's body, the graceful composition, and the charming mythological theme perfectly encapsulated the Academic ideal of beauty and technical perfection. Emperor Napoleon III himself purchased the painting for his personal collection, cementing Cabanel's status as a leading artist favored by the regime. The painting became one of the icons of 19th-century Academic art, widely reproduced and admired.

Interestingly, the same year, 1863, saw the infamous Salon des Refusés, an exhibition ordered by Napoleon III to display works rejected by the official Salon jury, on which Cabanel served. This counter-exhibition featured Édouard Manet's Le Déjeuner sur l'herbe, a work that scandalized the public with its modern subject matter and challenging style. The contrast between Cabanel's universally acclaimed Venus and Manet's rejected Déjeuner starkly highlighted the growing divide between the established Academic tradition and the emerging avant-garde. Cabanel's triumph represented the peak of official taste, while the Salon des Refusés signaled the stirrings of modernism.

The Academician: Professor and Juror

Cabanel's success at the 1863 Salon was swiftly followed by official recognition from the art establishment. That same year, he was elected to the prestigious Académie des Beaux-Arts, becoming one of the "Immortals" who presided over French artistic life. Membership in the Académie was the highest honor attainable for an artist within the traditional system. A year later, in 1864, he was appointed as a professor at the École des Beaux-Arts, a position he held until his death in 1889.

As a professor, Cabanel became one of the most influential teachers of his generation. His studio at the École attracted numerous students from France and abroad, eager to learn the techniques and principles that had brought him such success. He was known for being an encouraging, if demanding, instructor, guiding his pupils through the rigorous Academic curriculum focused on drawing from casts, life models, and studying the Old Masters. His teaching helped perpetuate the Academic style well into the late 19th century.

Among his many students were artists who achieved considerable fame in their own right, including Jules Bastien-Lepage, known for his blend of Academic technique and Naturalist subjects; Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant, famed for his Orientalist scenes and portraits; Fernand Cormon, whose studio later included Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and Vincent van Gogh; Édouard Debat-Ponsan; Pierre Auguste Cot, painter of the popular The Storm; Henri Regnault (a brilliant talent who died young in the Franco-Prussian War); Aristide Maillol (early in his career, before turning to sculpture); and Daniel Ridgway Knight. Through these students and many others, Cabanel's influence extended far beyond his own canvases.

Furthermore, his position as an Academician and respected professor meant he frequently served on the juries for the Paris Salon and the Prix de Rome competitions. This gave him considerable power in shaping official artistic taste and determining the career paths of younger artists. His known preference for traditional, highly finished works and his skepticism towards newer styles like Impressionism meant that artists working outside the Academic mold often faced rejection from the Salon, reinforcing his role as a gatekeeper of tradition.

Mature Style and Major Works

Throughout the 1860s, 70s, and 80s, Cabanel maintained a prolific output, solidifying his signature style. His work is characterized by impeccable draftsmanship, smooth and blended brushwork (the fini), idealized figures often based on classical prototypes, harmonious and carefully balanced compositions, and a refined, sometimes decorative, use of color. While capable of depicting dramatic scenes, his overall aesthetic leaned towards elegance, grace, and sensual beauty, often filtered through historical or mythological narratives.

Mythology remained a favorite source, allowing for the depiction of idealized nudes in classical settings. Following The Birth of Venus, he continued to explore such themes. History painting, considered the highest genre by the Academy, was also central to his oeuvre. He depicted scenes from ancient, biblical, and occasionally more recent history, always aiming for a sense of grandeur and decorum. Religious subjects were treated with similar refinement and idealized piety.

Beyond his famous Birth of Venus (1863) and the early Fallen Angel (1847), several other works stand out from his mature period. The Death of Francesca da Rimini and Paolo Malatesta (1870) tackles a tragic medieval theme inspired by Dante, rendered with dramatic intensity yet retaining Academic polish. Phaedra (1880) depicts the mythological queen consumed by forbidden desire, showcasing his ability to convey psychological tension within a classical framework. Ophelia (1883), inspired by Shakespeare's Hamlet, presents the tragic heroine floating towards her death amidst meticulously rendered flowers, a subject popular among both Academic and Pre-Raphaelite painters.

Cabanel was also a highly sought-after portrait painter. He captured likenesses of prominent figures of French society, European royalty, and wealthy American patrons (the "Gilded Age" elite). His portraits, like his history paintings, are marked by elegance, technical refinement, and a flattering idealization of the sitter. Notable examples include portraits of Napoleon III and members of the aristocracy. This aspect of his career brought him considerable financial success and further cemented his social standing.

Towards the end of his career, Cabanel also explored Orientalist themes, reflecting a broader European fascination with the cultures of North Africa and the Middle East. His painting Cleopatra Testing Poisons on Condemned Prisoners (1887) is a notable example, combining historical drama with exotic settings and costumes, typical of the genre popularized by artists like Jean-Léon Gérôme.

Cabanel and the Avant-Garde: A Bastion of Tradition

Alexandre Cabanel's career unfolded during a period of radical transformation in the art world. While he represented the pinnacle of the established Academic system, new movements were challenging its very foundations. Realism, led by Gustave Courbet, had already shocked the establishment in the 1850s. By the 1860s and 1870s, Impressionism emerged, spearheaded by artists like Claude Monet, Edgar Degas, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Camille Pissarro, and Berthe Morisot.

The Impressionists rejected the core tenets of Academic art. They favored contemporary subjects over historical or mythological ones, painted outdoors (en plein air) to capture fleeting effects of light and atmosphere, used visible brushstrokes and a brighter palette, and were less concerned with precise drawing and smooth finish. Their aesthetic was diametrically opposed to Cabanel's refined, idealized, and highly finished style.

As a leading member of the Academy and a frequent Salon juror, Cabanel found himself on the front lines of the conflict between tradition and modernity. His role in the 1863 Salon jury that rejected Manet's Le Déjeuner sur l'herbe is emblematic of his position. He and fellow Academicians, such as William-Adolphe Bouguereau and Jean-Léon Gérôme, viewed the Impressionists' work as unfinished, crude, and lacking in proper technique and elevated subject matter. They saw it as a threat to the standards of beauty and craftsmanship they upheld.

Cabanel consistently used his influence to oppose the acceptance of Impressionism into the official Salon. This stance led the Impressionists and their supporters, like the writer Émile Zola (who famously championed Manet and criticized Cabanel), to view him as a symbol of entrenched, outmoded artistic values. Zola, for instance, derided Cabanel's Venus as overly slick and artificial compared to the perceived truthfulness of Manet's Olympia (also shown in 1865, after being accepted to the Salon, causing another scandal). The opposition between Cabanel and the Impressionists thus became a defining narrative of late 19th-century French art history.

Themes, Techniques, and Critical Reception

Cabanel's thematic repertoire centered on the subjects deemed most noble by the Academy: history, mythology, religion, and allegory, alongside prestigious portrait commissions. His approach was consistently one of idealization. Whether depicting a goddess, a historical figure, or a contemporary sitter, he aimed for elegance, grace, and a timeless beauty derived from classical ideals. His nudes, particularly female ones like Venus, were celebrated for their smooth, flawless skin and languid poses, embodying a specific, highly refined eroticism acceptable within the bounds of official taste.

Technically, Cabanel was a virtuoso within the Academic framework. His drawing was impeccable, forming the solid foundation for his compositions. His handling of paint was characterized by meticulous blending, creating smooth, enamel-like surfaces where individual brushstrokes were largely invisible. This fini was highly valued by the Academy as a sign of skill and labor. His compositions were carefully constructed, often based on pyramidal or diagonal structures derived from Renaissance and Baroque masters. His color palette, while sometimes rich, tended towards harmonious and controlled effects rather than the vibrant, broken color of the Impressionists.

During his lifetime, Cabanel enjoyed immense critical acclaim from conservative critics and the public, alongside substantial official patronage. He was showered with honors, including being promoted to Commander of the Legion of Honour. However, critics aligned with the avant-garde, like Zola, attacked his work as artificial, overly sentimental, eclectic (drawing too obviously on past styles), and lacking in genuine emotion or originality. They saw his art as catering to the tastes of the bourgeoisie and the state, rather than pursuing artistic truth or innovation. This critical divide persisted long after his death.

Legacy and Reassessment

Alexandre Cabanel died in Paris on January 23, 1889, at the height of his fame but just as the artistic tide was definitively turning against the Academic tradition he represented. For much of the early 20th century, as Modernism triumphed, Cabanel and his Academic contemporaries like Bouguereau and Gérôme fell into critical disfavor. Their work was often dismissed as mere Kitsch, technically proficient but artistically empty and irrelevant to the progressive narrative of art history. His name became synonymous with the conservative forces that Impressionism had overthrown.

However, the later 20th and early 21st centuries have witnessed a significant reassessment of 19th-century Academic art. Art historians began to study figures like Cabanel not just as antagonists to the avant-garde, but as important artists in their own right, representing the dominant artistic culture of their time. Exhibitions and scholarly publications have shed new light on the complexities of Academicism, its aesthetic goals, its technical achievements, and its widespread appeal.

Today, Cabanel's works are prominently displayed in major museums, including the Musée d'Orsay in Paris (home to The Birth of Venus), the Musée Fabre in his native Montpellier (which holds a significant collection, including The Fallen Angel), and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (which owns a later version of the Venus). His paintings, particularly The Birth of Venus and The Fallen Angel, remain popular and widely reproduced images. While the criticisms regarding a certain artificiality or lack of profound originality persist, there is renewed appreciation for his exceptional technical skill, the elegance of his compositions, and his role as a master craftsman and influential teacher within his historical context. His legacy is complex: a symbol of an artistic system eventually superseded, yet an artist whose best works possess an undeniable beauty and technical brilliance that continue to engage viewers.

Conclusion

Alexandre Cabanel navigated the turbulent waters of 19th-century French art to become one of the most successful and celebrated painters of the Academic tradition. From his rigorous training under Picot and formative years in Rome to his triumphs at the Paris Salon and influential tenure as a professor at the École des Beaux-Arts, his career exemplified the possibilities and limitations of the official art system. His technically flawless, idealized depictions of mythological, historical, and religious subjects, epitomized by The Birth of Venus, earned him immense acclaim and patronage but also placed him in opposition to the rising tide of Impressionism and modern art. Though his reputation waned in the early 20th century, recent scholarship has fostered a more nuanced understanding of his achievements and his significant place in art history. Cabanel remains a key figure for understanding the dominant artistic tastes of his era and the profound cultural shifts that defined the transition to modernity.