Introduction: A Brief Flame in French Art

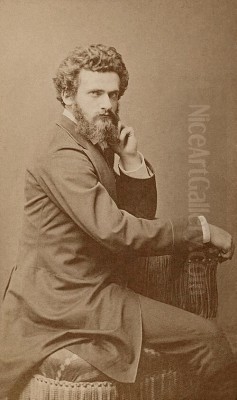

Alexandre-Georges-Henri Regnault, known to the art world as Henri Regnault, stands as one of the most promising and tragically short-lived figures in 19th-century French painting. Born in Paris on October 30, 1843, into a family of intellectual distinction, his life was a whirlwind of artistic development, exotic travels, and burgeoning fame, only to be cut short on the battlefield at the tender age of 27. In his brief career, Regnault blazed a trail with his vibrant Orientalist scenes, dramatic historical compositions, and a bold, almost rebellious approach to color and form that captivated the Parisian Salons and hinted at a genius that would never fully mature. His death in the Franco-Prussian War on January 19, 1871, transformed him into a national hero, a symbol of sacrificed youth and artistic potential, leaving behind a legacy that continues to fascinate art historians and enthusiasts alike.

Early Life and Artistic Inclinations

Henri Regnault was the son of Henri Victor Regnault, a highly distinguished chemist and physicist, and director of the Sèvres porcelain manufactory. This environment of scientific rigor and artistic craftsmanship undoubtedly played a role in shaping young Henri's worldview, though his passions leaned decisively towards the visual arts from an early age. He displayed a precocious talent for drawing and painting, demonstrating a natural aptitude for capturing the essence of animals, plants, and human figures. Unlike many of his contemporaries who followed a rigid academic path from childhood, Regnault's initial artistic explorations were largely self-driven, fueled by an innate curiosity and a keen observational eye.

His family, while perhaps initially hoping for a more conventional career, recognized his undeniable gift and supported his artistic ambitions. This support was crucial in allowing him the freedom to develop his skills. Paris, the undisputed art capital of the world in the 19th century, provided a rich tapestry of inspiration, from the masterpieces housed in the Louvre to the bustling studios and vibrant artistic debates that characterized the era. It was clear that Regnault was destined for a formal artistic education to hone his raw talent.

Formal Training and Influences

To refine his skills, Henri Regnault sought instruction from established masters. He entered the studio of Louis Lamothe, a painter known for his portraits and religious scenes, who had himself been a pupil of Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres. Lamothe would have instilled in Regnault a respect for classical drawing and composition. Later, and more significantly, Regnault became a student at the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, where he studied under Alexandre Cabanel. Cabanel was a towering figure in French academic art, celebrated for his historical, classical, and religious paintings, most famously The Birth of Venus (1863), which was a sensation at the Salon. Under Cabanel, Regnault would have been immersed in the academic tradition, focusing on life drawing, anatomical studies, and the grand manner of historical painting.

Despite this formal academic training, Regnault's artistic temperament was drawn to more expressive and dynamic influences. He was profoundly affected by the works of the great Romantic painters, particularly Eugène Delacroix and Théodore Géricault. Delacroix's vibrant use of color, his dramatic compositions, and his fascination with Orientalist themes resonated deeply with Regnault. Géricault's powerful depictions of human and animal energy, exemplified in works like The Raft of the Medusa and his studies of horses, also left an indelible mark on the young artist. These Romantic masters offered an alternative to the polished perfection of academic art, emphasizing emotion, movement, and the sublime.

In 1866, Regnault's dedication and talent were recognized when he won the coveted Prix de Rome for painting with his work Thetis Bringing the Arms Forged by Vulcan to Achilles. This prestigious award was a gateway to further study and artistic development, granting him a residency at the French Academy in Rome, housed in the Villa Medici. This achievement marked a significant milestone in his career, signaling his arrival as a major talent on the French art scene.

The Roman Sojourn and Travels

The Prix de Rome enabled Regnault to travel to Italy in 1867, taking up residence at the Villa Medici. Rome, with its layers of history, its classical ruins, and its Renaissance masterpieces, provided an immensely stimulating environment. Here, he was expected to produce works that demonstrated his mastery of classical themes and techniques, sending them back to Paris as proof of his progress. However, Regnault was not one to be strictly confined by academic expectations. While he absorbed the lessons of the Italian masters, his gaze was already turning towards other horizons.

His time in Italy was followed by extensive travels, most notably to Spain. Spain, with its rich Moorish heritage, its vibrant culture, and its dramatic landscapes, captivated Regnault. He was particularly drawn to the works of Spanish masters like Diego Velázquez and Francisco Goya, whose realism and psychological depth impressed him. In Spain, he encountered the work of Mariano Fortuny, a Catalan painter whose brilliant, sun-drenched Orientalist and genre scenes were immensely popular. Fortuny's dazzling technique and vibrant palette likely reinforced Regnault's own inclinations.

From Spain, Regnault ventured further south to North Africa, spending significant time in Tangier, Morocco. This experience was transformative. The intense light, the exotic colors, the unfamiliar customs, and the dramatic landscapes of North Africa provided him with a wealth of subject matter and profoundly influenced his artistic style. He became a leading figure in the Orientalist movement, which saw many European artists travel to the Middle East and North Africa in search of exotic and picturesque scenes. Unlike some Orientalists who depicted these cultures through a romanticized or stereotypical lens, Regnault's works often conveyed a sense of immediacy and raw energy. He even established a studio in Tangier, indicating a deep connection to the region.

Artistic Style and Orientalism

Henri Regnault's artistic style is characterized by its dynamism, its bold use of color, and its often dramatic or even violent subject matter. He successfully synthesized elements of Romanticism, Realism, and the burgeoning interest in Orientalism. His brushwork was often vigorous and expressive, a departure from the smooth, polished surfaces favored by many academic painters. He had a remarkable ability to capture the play of light and shadow, creating a sense of atmosphere and drama.

His Orientalist works are perhaps his most famous. He was fascinated by the perceived sensuality, cruelty, and splendor of the "Orient," a term then used to describe a vast and diverse region encompassing North Africa and the Middle East. His paintings often feature scenes of Moorish life, exotic figures, and dramatic historical or legendary events set in these locales. He employed a rich, vibrant palette, using strong contrasts of color to heighten the emotional impact of his scenes. For instance, he was known for innovative techniques, such as applying paint in thick impasto or even splashing and smearing it to achieve particular effects, especially for depicting the sheen of fabrics, the glint of metal, or the visceral quality of blood.

Regnault was not afraid to challenge academic conventions. While his training provided him with a strong foundation in drawing and composition, his artistic vision pushed him beyond traditional boundaries. His figures often possess a raw energy and a psychological intensity that set them apart. He was a master of depicting movement, whether it be the charge of horses, the swirl of dancers, or the tension of a dramatic confrontation. This freedom and boldness in his style made his works stand out at the Salons and garnered him both admiration and, at times, criticism from more conservative quarters.

Major Works

Despite his short career, Henri Regnault produced several masterpieces that cemented his reputation.

Automedon with the Horses of Achilles (1868)

Created during his time in Rome, this large-scale painting, now in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, depicts Automedon, Achilles' charioteer, struggling to control the hero's immortal horses, Xanthos and Balios. The work is a tour-de-force of dynamic energy and anatomical rendering. The powerful musculature of the horses, their wild eyes, and the straining figure of Automedon create a scene of intense struggle. The influence of Géricault, particularly his studies of horses, is evident. The painting combines a classical subject with a thoroughly Romantic execution, showcasing Regnault's ability to imbue traditional themes with a new vitality. Its dramatic composition and raw power were widely acclaimed.

General Juan Prim (1869)

This equestrian portrait of the Spanish general and statesman Juan Prim, a key figure in the 1868 revolution that overthrew Queen Isabella II of Spain, is another significant work. Regnault depicted Prim on a magnificent black charger, set against a dramatic, stormy sky. The painting, now in the Musée d'Orsay, Paris, captures the authority and charisma of its subject. It was exhibited at the Salon of 1869 and was a critical success, further enhancing Regnault's reputation. The work demonstrates his skill in portraiture and his ability to convey a sense of grandeur and historical moment.

Salomé (1870)

Perhaps one of his most iconic Orientalist works, Salomé (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) depicts the biblical seductress in a moment of contemplation, seated on a chest, a platter at her side, presumably awaiting the head of John the Baptist. Dressed in vibrant, exotic garments, Salomé is portrayed with a languid sensuality. The painting is notable for its rich colors, particularly the brilliant yellows and golds, and the intricate rendering of textures – silks, metals, and jewels. Regnault's Salomé is less overtly sinister than some interpretations, possessing an enigmatic, almost melancholic air. The work was a sensation at the Salon of 1870, admired for its technical brilliance and its exotic allure, though some critics found its sensuality unsettling. It became a quintessential image of 19th-century Orientalist fantasy and the femme fatale. Other artists like Gustave Moreau would also famously tackle the theme of Salomé, each bringing their unique Symbolist or decadent interpretations.

Execution without Judgment under the Moorish Kings of Granada (1870)

This large and dramatic painting (Musée d'Orsay, Paris) is one of Regnault's most powerful and disturbing works. It depicts a brutal scene of summary execution within the courtyard of a Moorish palace, likely inspired by the Alhambra in Granada. A richly dressed executioner calmly wipes his sword after decapitating a victim, whose body lies at the foot of a grand staircase, blood pooling vividly on the marble. The contrast between the opulent architectural setting, the brilliant sunlight, and the gruesome act creates a shocking impact. Regnault's use of color is particularly striking, with the bright red of the blood standing out against the cool tones of the stone. The painting explores themes of power, cruelty, and the exotic "other," common in Orientalist art, but with a visceral intensity that was Regnault's own. It was exhibited posthumously and caused a considerable stir, admired for its technical mastery but also criticized for its graphic violence. It can be compared to the meticulously detailed and often dramatic Orientalist scenes of Jean-Léon Gérôme, though Regnault's work often possessed a more untamed energy.

Judith

Another work that reflects his interest in strong, often dangerous, female figures from history and legend is Judith. While less universally known than Salomé, it aligns with his fascination for dramatic narratives and exotic settings, portraying the biblical heroine who saved her people by decapitating the Assyrian general Holofernes. Such themes allowed Regnault to explore intense emotions and create visually arresting compositions.

Contemporaries and the Artistic Milieu

Henri Regnault worked during a period of immense artistic ferment in Paris. The official art world was dominated by the Académie des Beaux-Arts and the annual Salon, where academic painters like his teacher Alexandre Cabanel, Jean-Léon Gérôme, William-Adolphe Bouguereau, and Ernest Meissonier enjoyed enormous prestige and commercial success. These artists upheld the traditions of historical painting, meticulous realism, and idealized beauty.

However, new artistic currents were emerging. The Realist movement, championed by Gustave Courbet, had already challenged academic conventions by focusing on contemporary life and ordinary people. More radically, the artists who would become known as the Impressionists – Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Edgar Degas, Camille Pissarro, Berthe Morisot, and Alfred Sisley – were beginning to develop their revolutionary approach to capturing light and fleeting moments, often painting en plein air. While Regnault was a product of the academic system and achieved Salon success, his vibrant color, expressive brushwork, and dramatic intensity set him apart from the more staid academicism of some of his peers.

He was friends with fellow artists, including Georges Clairin, who also became known for his Orientalist paintings and portraits, and the composer Camille Saint-Saëns. He was also acquainted with the architect Charles Garnier, who designed the opulent Paris Opéra. His letters reveal a lively, passionate individual, deeply engaged with art, music, and literature. He was part of a generation of young artists eager to make their mark, navigating the established structures of the art world while also seeking new forms of expression. His fiancée, Geneviève Bréton, came from an intellectual family, and their correspondence provides insights into his thoughts and aspirations.

The Franco-Prussian War and Tragic Demise

The trajectory of Henri Regnault's brilliant career was tragically interrupted by the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War in July 1870. France, under Emperor Napoleon III, declared war on Prussia, leading to a swift and disastrous conflict for the French. Regnault was in Tangier when the war began. Despite being exempt from military service due to his status as a Prix de Rome winner, he felt a patriotic duty to defend his country. He returned to Paris, which was soon besieged by Prussian forces.

He enlisted in the 69th battalion of the Garde Nationale (National Guard) as a common soldier. The siege of Paris was a period of great hardship, with food shortages and constant bombardment. Regnault participated in the defense of the city. On January 19, 1871, during the Battle of Buzenval, one of the last attempts by the besieged Parisians to break the Prussian lines, Henri Regnault was killed in action. He was shot through the temple. Paris capitulated shortly thereafter, and the war officially ended in May 1871 with the Treaty of Frankfurt.

Regnault's death at the age of 27 sent shockwaves through the French art world and the nation. He was mourned as a fallen hero, a brilliant talent extinguished in its prime. His sacrifice became a potent symbol of French patriotism and the tragic losses of the war. His body was eventually interred in the Panthéon, a mausoleum for distinguished French citizens, though later reinterred. The circumstances of his death, fighting for his country, amplified his posthumous fame and contributed to the mythologizing of his figure.

Legacy and Posthumous Reputation

The death of Henri Regnault was a profound loss for French art. His posthumous reputation was immense, fueled by both his artistic achievements and his heroic sacrifice. His works were exhibited to great acclaim, and his name became synonymous with youthful genius cut short. He was seen as a martyr for France, and his story resonated deeply in the aftermath of the humiliating defeat and the subsequent turmoil of the Paris Commune.

His art, particularly his Orientalist paintings, continued to be popular and influential. However, as artistic tastes shifted towards Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, Regnault's more Romantic and academic-leaning style gradually fell out of favor with the avant-garde. Nevertheless, his technical brilliance, his vibrant use of color, and the sheer energy of his work ensured his place in the annals of 19th-century art.

In more recent times, there has been a renewed interest in Regnault's work, partly due to a broader reassessment of 19th-century academic and Orientalist art. Art historians like Marc Gotlieb, in his book "The Deaths of Henri Regnault," have explored his life, his art, and the complex ways in which his death shaped his legacy and became part of France's public memory. His paintings are now found in major museums around the world, testament to his enduring appeal.

Regnault's legacy is multifaceted. He was a painter of extraordinary talent who, in a very short time, produced a body of work characterized by its vibrancy, drama, and technical skill. He was a key figure in the Orientalist movement, contributing memorable and powerful images to that genre. And he became a national icon, a symbol of artistic promise and patriotic sacrifice. While one can only speculate on what he might have achieved had he lived longer, the works he left behind are a powerful reminder of his meteoric talent.

Conclusion: An Unfinished Symphony

Henri Regnault's life was like a brilliant, intense flame that burned out far too quickly. In just a few years of active artistic production, he demonstrated a mastery of color, composition, and emotional expression that placed him at the forefront of his generation. His journeys to Spain and North Africa infused his work with an exoticism and vitality that captivated audiences, while his historical and mythological scenes pulsed with Romantic energy. His tragic death on the battlefield transformed him from a rising star into a legendary figure, a martyr for art and for France.

Though his career was tragically brief, Henri Regnault left an indelible mark on 19th-century French art. His paintings continue to fascinate with their blend of academic skill, Romantic passion, and Orientalist allure. He remains a compelling figure, a testament to the power of youthful genius and a poignant reminder of potential unfulfilled. His art serves as an unfinished symphony, hinting at the even greater masterpieces that might have been, yet powerful and resonant in its existing form.