Ary Scheffer stands as a significant, albeit sometimes debated, figure in the landscape of 19th-century European art. Born in the Netherlands but spending his formative and most productive years in France, he navigated the complex artistic currents of his time, blending elements of Neoclassicism with the burgeoning spirit of Romanticism. His work, often inspired by literature, religion, and contemporary history, resonated deeply with audiences during his lifetime, even as it drew criticism from proponents of more radical artistic shifts. Scheffer's life and career offer a fascinating glimpse into the artistic, social, and political milieu of post-Napoleonic France.

Early Life and Artistic Foundations

Ary Scheffer was born on February 10, 1795, in Dordrecht, Holland, then part of the Batavian Republic under French influence. Artistic talent ran in the family; his father, Johan Baptist Scheffer, was a German-born painter specializing in portraits and historical subjects who had settled in the Netherlands. His mother, Cornelia Lamme, was also an accomplished artist, known for portrait miniatures. This environment undoubtedly nurtured young Ary's artistic inclinations. His father served briefly as a court painter to Louis Bonaparte, Napoleon's brother, who was installed as King of Holland in 1806.

Following his father's early death in 1809, Ary's determined mother moved the family, including Ary and his two brothers, Henry and Arnold, to Paris in 1811. She recognized that the French capital was the epicenter of the European art world and offered the best opportunities for her sons' artistic education and careers. Henry Scheffer also became a notable painter, often working in a style similar to Ary's.

In Paris, Ary Scheffer enrolled in the studio of Baron Pierre-Narcisse Guérin, a prominent Neoclassical painter and a follower of the great Jacques-Louis David. Guérin's studio was a crucible of talent; Scheffer studied alongside future giants of French Romanticism, including Eugène Delacroix and Théodore Géricault. Although trained in the Neoclassical principles of clear lines, balanced composition, and historical or mythological subject matter, Scheffer, like Delacroix and Géricault, soon began to explore the more emotionally charged and individualistic avenues of Romanticism.

Emergence in the Parisian Art World

Scheffer began exhibiting at the prestigious Paris Salon in 1812, initially presenting works that reflected his Neoclassical training but increasingly showed a penchant for sentimental and patriotic themes drawn from recent history or everyday life. Early successes like The Soldier's Widow (La Veuve du Soldat, 1817) and The Conscript's Departure (Le départ du conscrit) resonated with the public's post-Napoleonic War sentiments. These works demonstrated his skill in rendering human emotion with sensitivity, a trait that would become characteristic of his mature style.

His technical proficiency and ability to capture pathos quickly gained him recognition. He developed a distinct approach, often characterized by careful draftsmanship inherited from his Neoclassical training, combined with a softer, more atmospheric use of light and a focus on psychological states that aligned with Romantic sensibilities. He was less interested in the dramatic, often violent, energy found in the works of Géricault or Delacroix, preferring quieter, more introspective moments.

This period saw him begin to tackle subjects from literature, a field that would provide fertile ground for his imagination throughout his career. His connections within the Parisian artistic and intellectual circles grew, laying the groundwork for his later prominence not just as a painter, but also as a central figure in a vibrant cultural salon.

Literary Inspirations: Dante, Goethe, and Byron

A significant portion of Ary Scheffer's fame rests on his interpretations of literary masterpieces. He possessed a deep affinity for the works of Dante Alighieri, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, and Lord Byron, poets whose themes of love, loss, sin, redemption, and the supernatural strongly resonated with the Romantic ethos. Scheffer translated their powerful narratives into visual form, creating images that became iconic representations of these literary scenes for the 19th-century public.

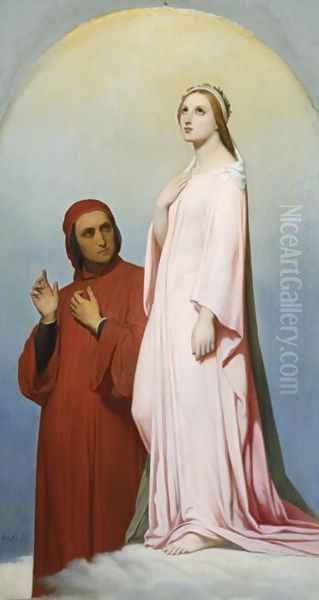

His paintings based on Dante's Divine Comedy were particularly popular. Francesca da Rimini and Paolo Malatesta Appraised by Dante and Virgil (1835 version, Wallace Collection; later versions exist), depicting the tragic lovers condemned to the second circle of Hell, became one of his most celebrated works. Its blend of ethereal beauty, restrained passion, and profound sorrow captivated audiences. Another key Dante-inspired work is Dante and Beatrice (various versions, e.g., 1840s), often showing Beatrice guiding Dante, embodying spiritual love and divine guidance with a characteristic blend of idealism and melancholy.

Goethe's Faust provided another rich source of inspiration. Scheffer painted numerous scenes from the drama, focusing on the tragic figure of Marguerite (Gretchen). Marguerite at the Spinning Wheel, Marguerite Leaving Church, and Faust in his Study are among his well-known interpretations. These works often emphasize Marguerite's innocence, piety, and eventual despair, rendered with Scheffer's typical sensitivity and delicate handling of light and expression. Marguerite at the Well is another poignant example from this series.

Lord Byron's exotic and often melancholic poetry also appealed to Scheffer. He painted scenes from Byron's works, such as The Giaour, capturing the dramatic intensity and romantic settings characteristic of the poet. Through these literary paintings, Scheffer demonstrated his ability to convey complex emotional narratives and abstract concepts visually, contributing significantly to the Romantic movement's engagement with literature.

Religious and Historical Themes

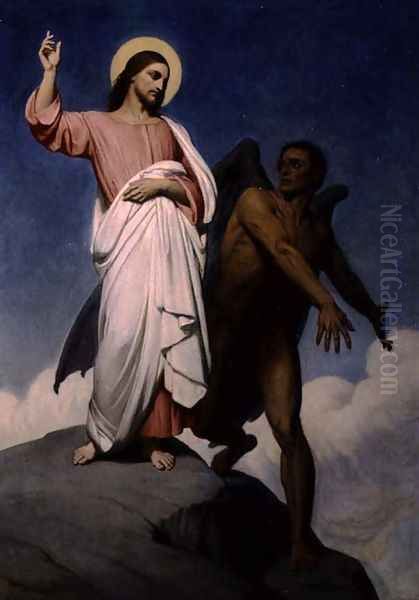

Alongside his literary subjects, Scheffer devoted considerable energy to religious painting, particularly in his later career. His approach to sacred themes was often imbued with the same emotional sensitivity and introspective quality found in his literary works. He sought to portray the spiritual and psychological dimensions of faith, often focusing on moments of contemplation, suffering, or divine comfort.

One of his most famous religious paintings is Christus Consolator (Christ the Comforter, 1837). This large-scale work depicts Christ offering solace to a diverse group of suffering individuals throughout history, embodying a universal message of compassion and redemption. The painting was immensely popular and widely reproduced, reflecting the era's blend of religious sentiment and humanitarian concern.

Another significant religious work is Saint Augustine and his Mother, Saint Monica (1846, versions in the National Gallery, London and the Louvre). Based on Augustine's Confessions, the painting portrays the mother and son in a moment of shared spiritual ecstasy and contemplation, looking towards the heavens. Scheffer masterfully conveys their profound inner connection and shared faith through subtle gestures and expressions, set against a serene background. The work is noted for its quiet intensity and emotional depth, rendered in his characteristically refined style.

Scheffer also painted historical subjects and portraits. His connection to the Orléans family provided numerous commissions, including portraits of King Louis-Philippe I, Queen Marie-Amélie, and their children, such as Ferdinand Philippe, Duke of Orléans, and Princess Marie d'Orléans, who was herself a talented sculptor and Scheffer's student. These portraits often combined formal representation with a degree of psychological insight, reflecting his ability to capture likeness while hinting at the sitter's personality.

Artistic Style: The "Frigid Classicism"

Scheffer's style is often described as occupying a middle ground between the disciplined lines of Neoclassicism, as practiced by his teacher Guérin or the dominant Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, and the vibrant color and dynamic energy of High Romanticism, exemplified by Eugène Delacroix. Critics, both contemporary and later, sometimes found his style lacking the formal rigor of Ingres or the passionate intensity of Delacroix.

His color palette tended towards subtlety, often employing muted tones, sfumato (soft, hazy transitions between colors), and a careful modulation of light and shadow to create atmosphere and focus attention on the figures' emotional states. This contrasted sharply with Delacroix's bold use of complementary colors and expressive brushwork. Scheffer prioritized sentiment and narrative clarity, sometimes at the expense of painterly bravura.

His figures are typically elegant and idealized, drawn with precision yet imbued with a palpable sense of inner life. He excelled at depicting tender emotions, melancholy, and spiritual longing. This led some critics, like Charles Baudelaire, to dismiss his work as overly sentimental or lacking in genuine passion, sometimes labeling his style as "frigid classicism" or suggesting it appealed primarily to popular taste rather than artistic connoisseurs.

However, this characterization doesn't fully capture the nuances of his work. Scheffer consciously crafted a style that aimed for emotional resonance through refinement and restraint rather than overt drama. His emphasis on psychological depth and his ability to create poignant, memorable images ensured his widespread appeal and influence during his lifetime. His technical skill, particularly in draftsmanship and the rendering of textures and expressions, remained consistently high throughout his career.

The Scheffer Studio: A Hub of Romantic Paris

Beyond his own artistic production, Ary Scheffer played a significant role in the cultural life of Paris through the salon he hosted at his home and studio complex in the Nouvelle Athènes district (now the location of the Musée de la Vie Romantique). From the 1830s onwards, his Friday evening gatherings became a meeting point for leading figures from the worlds of art, music, literature, and politics.

His studio wasn't just a place of work but a social nexus where ideas were exchanged and collaborations sometimes sparked. Regular attendees included composers like Frédéric Chopin and Franz Liszt, writers such as George Sand (who lived nearby) and Charles Dickens, the singer Pauline Viardot, the painter Eugène Delacroix (despite their stylistic differences, they maintained a complex professional relationship), and political figures associated with the Orléanist regime.

This vibrant circle reflected Scheffer's broad intellectual interests and his respected position within Parisian society. The presence of figures like Chopin, whose music often shares a similar blend of technical refinement and emotional depth with Scheffer's paintings, highlights the cross-pollination between the arts during the Romantic era. Scheffer painted famous portraits of both Chopin and Liszt, capturing their intense artistic personalities. His portrait of Chopin, painted during the composer's illness, is particularly renowned for its sensitivity.

The atmosphere of these gatherings, fostering intellectual and artistic exchange, contributed to the cultural ferment of the July Monarchy period. Scheffer's role as a host and cultural mediator cemented his status as more than just a painter; he was an integral part of the Romantic movement's social fabric.

Royal Patronage and Political Engagement

Scheffer's career was significantly boosted by his close ties to the Orléans family. In 1822, he was appointed drawing master to the children of Louis-Philippe, then Duke of Orléans. This position provided him with financial stability and invaluable access to the highest levels of French society. His students included the future King Leopold I of Belgium (who married Louis-Philippe's daughter Louise) and Princess Marie d'Orléans, who became a respected sculptor under his guidance.

When Louis-Philippe ascended the throne as King of the French after the July Revolution of 1830, Scheffer's position as a favored artist of the ruling family was solidified. He received numerous commissions for portraits and historical paintings celebrating the Orléanist dynasty. His political sympathies clearly lay with the liberal Orléanist monarchy, which positioned itself as a 'juste milieu' (middle way) between the extremes of republicanism and legitimist reaction.

Scheffer actively participated in the events of 1830, serving in the National Guard alongside his brother Henry. His loyalty and connections earned him official recognition, including being made an Officer of the Legion of Honour in 1830. His proximity to power, however, also linked his reputation to the fortunes of the July Monarchy. While it brought him success and patronage, it also meant that his popularity waned somewhat after the Revolution of 1848, which overthrew Louis-Philippe. Scheffer, disillusioned by the political turmoil and the rise of Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte (Napoleon III), largely withdrew from political life in his later years. He had become a French citizen in 1846, formalizing his deep connection to his adopted country.

Analysis of Key Works

Several paintings stand out as particularly representative of Scheffer's oeuvre and impact:

Francesca da Rimini and Paolo Malatesta (1835 version): This work exemplifies Scheffer's ability to blend sensuality with pathos. The ghostly, intertwined figures of the lovers float through the infernal gloom, observed by Dante and Virgil. Scheffer's delicate modeling, muted colors, and focus on the tragic embrace create an image of enduring, sorrowful love that became immensely popular and widely reproduced, influencing subsequent depictions of the scene by artists like Gustave Doré.

Saint Augustine and Saint Monica (1846): A masterpiece of quiet spiritual intensity. The composition is simple yet powerful, focusing entirely on the two figures silhouetted against a luminous sky. Their shared upward gaze and subtly differentiated expressions convey a profound moment of mystical connection described in Augustine's Confessions. The painting's serene atmosphere and refined execution showcase Scheffer's mature religious style, emphasizing contemplation over dogma.

Christus Consolator (1837): This ambitious work demonstrates Scheffer's engagement with contemporary social and humanitarian concerns, framed within a religious context. By depicting Christ comforting figures representing various forms of human suffering (slavery, poverty, oppression, grief), Scheffer created a powerful allegory of universal compassion that resonated deeply with the 19th-century public's growing social conscience. Its eclecticism and sentimental appeal made it one of his most famous works.

Portrait of Frédéric Chopin (1847): More than just a likeness, this portrait captures the frail intensity of the composer near the end of his life. Scheffer uses dramatic lighting (chiaroscuro) and focuses tightly on Chopin's face, conveying both his physical suffering and his passionate artistic spirit. It remains one of the most iconic images of the composer.

These works highlight Scheffer's strengths: his narrative clarity, his focus on psychological and emotional states, his refined technique, and his ability to create images that struck a chord with the sentiments of his time.

Contemporaries, Influence, and Critical Reception

Ary Scheffer occupied a unique position relative to his most famous contemporaries. He was less revolutionary in technique and color than Eugène Delacroix, whose dramatic historical scenes like Liberty Leading the People or Death of Sardanapalus defined High Romanticism's energy. Scheffer's work offered a quieter, more introspective form of Romanticism.

Compared to Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, the staunch defender of Neoclassical line and form, Scheffer appeared more modern in his emotionalism and choice of contemporary literary themes. Yet, he retained a classical sense of balance and finish that Ingres would have appreciated, even if Ingres likely disapproved of Scheffer's overt sentimentality. Scheffer navigated a path between these two dominant figures.

Other important contemporaries included Paul Delaroche, known for his highly detailed and often melodramatic historical scenes, and Horace Vernet, immensely popular for his military paintings and battle scenes. Scheffer's work shared with Delaroche a focus on historical and literary narrative but generally avoided overt melodrama in favor of psychological depth.

His influence extended through his teaching and the popularity of his works, which were widely disseminated through engravings. His sentimental style appealed greatly to Victorian tastes in Britain and influenced artists there. His daughter, Cornélie Scheffer, also became a painter, carrying on the family's artistic tradition.

Critical reception during his lifetime was largely positive, especially during the July Monarchy. However, as artistic tastes shifted towards Realism (led by Gustave Courbet) and later Impressionism, Scheffer's work began to seem dated to progressive critics. Figures like Baudelaire criticized his perceived lack of vigor and his sometimes formulaic approach to emotion. His reputation declined significantly in the later 19th and early 20th centuries.

Later Years and Legacy

The Revolution of 1848 marked a turning point for Scheffer. The fall of his patron, Louis-Philippe, and his disillusionment with the ensuing political developments led him to retreat somewhat from public life. While he continued to paint, his later works often focused more exclusively on religious themes, characterized by an increasingly austere and spiritual quality. He exhibited less frequently at the Salon.

He suffered from heart disease in his later years. Ary Scheffer died on June 15, 1858, in Argenteuil, near Paris, shortly after traveling to England for the funeral of the Duchess d'Orléans. He was buried in the Montmartre Cemetery in Paris, a resting place for many prominent artists and writers.

His legacy is complex. For decades after his death, his work was often overlooked or dismissed as overly sentimental and academic. However, late 20th and early 21st-century art history has seen a renewed interest in artists who occupied the "juste milieu" and a greater appreciation for the diversity of 19th-century art beyond the canonical avant-garde movements.

Today, Scheffer is recognized as a key figure of French Romanticism, particularly skilled in interpreting literary and religious themes with emotional sensitivity and technical refinement. His home and studio were preserved and eventually transformed into the Musée de la Vie Romantique (Museum of Romantic Life) in Paris. This museum, dedicated to Scheffer, George Sand, and the Romantic era, stands as a testament to his central role in the cultural life of his time. His works are held in major museums worldwide, including the Louvre and Musée d'Orsay in Paris, the Wallace Collection and National Gallery in London, the Dordrechts Museum in his hometown, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

Conclusion: An Enduring Romantic Sensibility

Ary Scheffer's art provides a crucial link between the fading ideals of Neoclassicism and the full flowering of Romanticism. While perhaps lacking the revolutionary fervor of Delacroix or the linear purity of Ingres, he carved out a distinct and influential niche. His ability to translate profound literary and religious narratives into accessible, emotionally resonant images captivated a vast audience. His paintings, characterized by their technical polish, psychological depth, and often melancholic beauty, spoke directly to the sentiments of the 19th century. Though his fame fluctuated with changing artistic tastes, Ary Scheffer remains an important artist whose work continues to offer insights into the complex soul of the Romantic era, bridging the gap between historical tradition and modern emotional expression. His enduring legacy is preserved not only in his paintings but also in the museum that now occupies his former home, forever marking his place in the heart of Romantic Paris.