Alfred William Finch, often known as Willy Finch, stands as a fascinating and somewhat unique figure in the annals of late 19th and early 20th-century European art. Born in Brussels to British parents in 1854 and passing away in Helsinki in 1930, his life and career bridged multiple cultures and artistic disciplines. Primarily recognized for his contributions as a painter in the Neo-Impressionist style and later as a highly influential ceramicist, Finch played a pivotal role in the dissemination of avant-garde ideas, particularly between Belgium, Britain, and Finland. His journey reflects the dynamic artistic exchanges of the era, a commitment to modernist principles, and a remarkable adaptability that saw him transition from the canvas to the kiln with enduring success.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Brussels

Alfred William Finch's upbringing in Brussels, a vibrant cosmopolitan center, exposed him to a rich tapestry of cultural influences from a young age. Though his parents, Joseph Finch and Emma Finch (née Holach), were British, their son's formative artistic education took place within the Belgian system. He spent his youth in Ostend, a coastal city that would later feature in his art, before enrolling at the Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts in Brussels. This institution, while traditional, was also a crucible where young artists began to question established norms.

During these early years, Finch's work was initially aligned with a form of realism, likely influenced by contemporary Belgian painters who were themselves moving away from strict academicism. Artists like Guillaume Vogels, known for his atmospheric and somewhat somber landscapes, were part of this milieu. The artistic climate in Brussels was one of ferment, with artists increasingly seeking new modes of expression that could capture the realities of modern life and the fleeting effects of light and atmosphere, a concern that would become central to Finch's later painterly practice.

The Revolutionary Spirit of Les XX

A defining moment in Finch's early career, and indeed in the history of Belgian modern art, was his involvement as a founding member of "Les XX" (The Twenty) in 1883. This exhibiting society, spearheaded by the lawyer and arts promoter Octave Maus, was established in direct opposition to the conservative Salon system and the prevailing academic standards. Les XX aimed to provide a platform for progressive and avant-garde art, not only from Belgium but internationally. It quickly became one of the most important and radical art groups in Europe.

Finch, alongside fellow Belgian artists such as James Ensor, Fernand Khnopff, Théo van Rysselberghe, and Anna Boch, was integral to this rebellious spirit. Les XX was not defined by a single style but by a shared desire for artistic freedom and innovation. Their annual exhibitions were legendary, showcasing a wide array of styles from Symbolism to Impressionism and, crucially for Finch, Neo-Impressionism. The group invited prominent international artists to exhibit with them, creating an unparalleled forum for artistic dialogue. Luminaries such as Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, Auguste Renoir, Auguste Rodin, and James McNeill Whistler all showed their work at Les XX exhibitions.

Embracing Neo-Impressionism: The Science of Light

The most profound impact on Finch's painting style came through Les XX's introduction of French Neo-Impressionism to Brussels. Georges Seurat's monumental painting, A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte, was exhibited at Les XX in 1887, causing a sensation. Seurat, alongside Paul Signac, had developed the technique of Pointillism (or Divisionism), which involved applying small, distinct dots of pure color to the canvas, relying on the viewer's eye to optically blend them. This method was grounded in contemporary scientific theories of color and light.

Finch was one of the first Belgian artists to enthusiastically adopt this new approach. He became a devoted practitioner of Neo-Impressionism, meticulously applying dots of color to create luminous and vibrant depictions of landscapes and coastal scenes. His work from this period demonstrates a keen understanding of color theory and a desire to capture the transient effects of light with scientific precision yet artistic sensitivity. He was in good company, as Théo van Rysselberghe also became a leading Belgian Neo-Impressionist, and they, along with others like Henry van de Velde (who would later become more famous as an architect and designer), championed this style. Other French Neo-Impressionists who influenced or were part of this circle included Henri-Edmond Cross and Maximilien Luce.

Masterworks in Pointillism

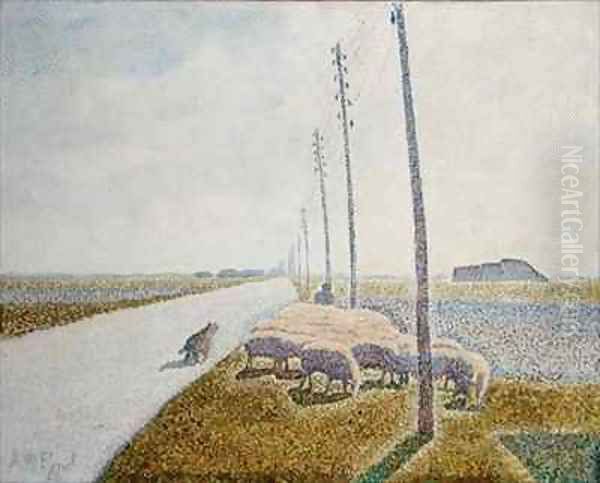

During his Neo-Impressionist phase, Finch produced some of his most celebrated paintings. These works often depicted the landscapes and coastal environments he knew well, imbued with the shimmering light characteristic of the style.

The Wellington Racetrack in Ostend under Drizzle (1888) is a prime example, showcasing his ability to capture a specific atmospheric condition – the soft, diffused light of a rainy day – through the meticulous application of color dots. The scene is vibrant despite the weather, with the greens of the track and the varied colors of the spectators and horses rendered with a delicate luminosity.

Another significant work is The White Cliffs of Dover (c. 1892). This painting, depicting the iconic English landmark, highlights his British connections and his interest in capturing the interplay of light on water and chalk. The cliffs rise majestically, their whiteness fractured into a multitude of hues by the Pointillist technique, set against a sparkling sea and sky.

Other notable paintings from this period include Breakwaters at Heyst (1889), The Road to Nieuport, and An English Lane. These works consistently demonstrate his commitment to the Neo-Impressionist method, focusing on the optical effects of color and light to convey the essence of a scene. His subjects ranged from the bustling activity of The Port of London to the tranquility of A Garden in Yorkshire or The Valley of Amberley. Even urban scenes like Park Theatre or The Theatre Box were approached with the same analytical yet poetic application of color. Works like The Orchard at La Louvière (or The Domain of La Louvière) and The Bushes at Oudenarde further exemplify his dedication to landscape, rendered with a vibrant, dotted technique.

The Transition to Ceramics: A New Artistic Path

Despite his critical engagement with painting and his role within the avant-garde, Finch, like many artists of the time, found it challenging to make a consistent living solely from his canvases. By the early 1890s, economic pressures led him to explore other avenues. This practical necessity, however, opened up a new and profoundly influential chapter in his artistic career: ceramics.

This shift was not an abandonment of his artistic principles but rather a translation of them into a new medium. The Arts and Crafts movement, originating in Britain with figures like William Morris, was gaining traction across Europe, advocating for the artistic value of craftsmanship and the integration of art into everyday life. Finch's move into ceramics can be seen within this broader context, where the distinctions between fine art and applied arts were beginning to blur. His painterly concern for color, texture, and form found new expression in three-dimensional objects.

A Pivotal Role in Finland: The Iris Workshop and Jugendstil

In 1897, Finch's career took a significant international turn when he was invited by the Finnish-Swedish artist Count Louis Sparre to move to Porvoo, Finland. Sparre had founded the Iris Company, an ambitious enterprise dedicated to producing high-quality furniture and ceramics in the modern style, akin to Art Nouveau or, as it was known in German-speaking countries and Scandinavia, Jugendstil. Finch was appointed to lead the ceramics department.

His arrival in Finland was transformative, both for Finch and for Finnish applied arts. He brought with him a wealth of experience from the vibrant art scene of Brussels and a sophisticated understanding of contemporary design principles. At the Iris factory, Finch introduced new glazing techniques and modern forms, moving away from overly ornate decoration towards simpler, more elegant designs that emphasized the quality of the material and the beauty of the glaze. His ceramics often featured rich, flowing glazes with subtle color variations, reminiscent of his Pointillist paintings' concern with light and color.

Finch's work at Iris had a profound impact on the development of Finnish Jugendstil. He trained a generation of Finnish ceramicists, including Sigurd Frosterus, who would later become a prominent architect and critic. Finch's influence helped to elevate the status of ceramics in Finland, aligning it with the broader national romantic and modernist aspirations of the era. Artists like Akseli Gallen-Kallela, a towering figure in Finnish painting, and Eliel Saarinen, a leading architect, were part of this cultural flourishing, and Finch's contributions in the applied arts were a vital component of this "Golden Age" of Finnish art. His work was exhibited internationally, including at the 1900 Paris Exposition Universelle, where Iris ceramics received acclaim.

Finch's Ceramic Art: Style and Significance

The ceramics produced under Finch's direction at the Iris factory, and his own individual pieces, are characterized by their elegant simplicity of form and their sophisticated glazes. He experimented extensively with high-temperature firing and developed a range of distinctive glazes, often with crystalline or flowing effects. The colors were typically subtle and harmonious, reflecting an aesthetic that valued refinement over ostentation.

His approach was rooted in an understanding of the ceramic tradition but was also thoroughly modern. He drew inspiration from East Asian ceramics, particularly their emphasis on form and glaze, but adapted these influences to a contemporary European sensibility. The objects produced – vases, bowls, tiles – were intended to be both beautiful and functional, embodying the Arts and Crafts ideal of art for daily life. His contribution was crucial in establishing a modern ceramics tradition in Finland, one that valued both technical skill and artistic vision.

Later Years: A Return to Painting and Enduring Legacy

Although ceramics became a major focus, Finch never entirely abandoned painting. After his intensive period with the Iris factory (which closed in 1902), he continued to work as an independent artist and teacher in Helsinki. He taught ceramics at the Central School of Industrial Arts (a precursor to the Aalto University School of Arts, Design and Architecture) from 1902 until 1927, influencing another generation of Finnish artists and designers.

In his later years, he increasingly returned to painting, often depicting Finnish landscapes as well as scenes from his travels, including further works inspired by England. These later paintings, while perhaps not as strictly Pointillist as his earlier works, retained a sensitivity to light and color that had always characterized his art. He continued to exhibit his work, and his paintings and ceramics found their way into important collections.

Alfred William Finch passed away in Helsinki in 1930, leaving behind a rich and diverse body of work. His legacy is multifaceted. As a painter, he was a key figure in the Belgian avant-garde, an early and committed adopter of Neo-Impressionism who helped to disseminate its principles. His paintings are celebrated for their luminosity and their sensitive depiction of light and atmosphere.

As a ceramicist, his impact, particularly in Finland, was profound. He played a crucial role in the development of Finnish Jugendstil and helped to establish a modern tradition of art pottery in the country. His work at the Iris factory set a high standard for design and craftsmanship and influenced Scandinavian design more broadly.

Conclusion: A Bridge Between Nations and Disciplines

Alfred William Finch's career is a testament to the interconnectedness of European art at the turn of the 20th century. A man of British parentage, educated in Belgium, who found his mature artistic voice amidst the Neo-Impressionist revolution and later became a foundational figure in Finnish applied arts, Finch embodied the transnational flow of ideas. He was a bridge-builder, not only between countries but also between artistic disciplines, demonstrating that the principles of light, color, and form could find equally compelling expression on canvas and in clay.

His association with Les XX places him at the heart of European modernism, alongside figures like Ensor, Khnopff, and international invitees like Seurat, Signac, Monet, and Rodin. His engagement with Neo-Impressionism connects him to a pivotal movement that sought to bring scientific rationality to the depiction of visual experience. His later career in Finland, working with Sparre and influencing Frosterus and others, highlights his importance in the Arts and Crafts and Art Nouveau movements, contributing to a distinctively Finnish modern aesthetic alongside contemporaries like Gallen-Kallela and Saarinen.

Finch's journey from the avant-garde circles of Brussels to the burgeoning art scene of Helsinki, from the meticulous dots of Pointillism to the flowing glazes of art pottery, marks him as an artist of remarkable versatility and enduring significance. His works continue to be admired for their beauty, their technical skill, and the unique artistic vision that shaped them, securing his place as an important, if sometimes overlooked, pioneer of modern European art and design.