Willy Schlobach (1864-1951) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the vibrant tapestry of late 19th and early 20th-century European art. A Belgian painter of German descent, Schlobach was instrumental in the dissemination of Neo-Impressionist ideas and techniques within Belgium, primarily through his active role as a founding member of the avant-garde group Les XX (Les Vingt). His work, characterized by a meticulous application of color and a profound sensitivity to light and atmosphere, reflects both the scientific rigor of Pointillism and a deeply personal engagement with the natural world.

Early Artistic Formation and Influences

Born in Brussels in 1864 (some sources state 1865), Willy Schlobach embarked on his artistic journey with formal training at the prestigious Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts in Brussels. This institution, like many European academies of the time, would have provided a solid grounding in traditional drawing and painting techniques. However, the late 19th century was a period of immense artistic ferment, with new movements challenging academic conventions. Brussels, in particular, was becoming a dynamic center for avant-garde art, receptive to innovations emanating from Paris and elsewhere.

Schlobach's artistic development was profoundly shaped by the revolutionary currents of his time. The Impressionist movement, pioneered by artists like Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, and Auguste Renoir, had already redefined the way artists perceived and depicted light and fleeting moments. Their emphasis on outdoor painting (en plein air) and the subjective experience of vision laid the groundwork for further experimentation.

Following Impressionism, Neo-Impressionism emerged in the mid-1880s, spearheaded by Georges Seurat and Paul Signac. This movement sought to bring a more scientific and systematic approach to the depiction of light and color. Seurat's theory of Divisionism (also known as Chromoluminarism), and its practical application through Pointillism – the use of small, distinct dots of pure color intended to mix optically in the viewer's eye – captivated a generation of young artists. Schlobach was among those who keenly absorbed these new principles, particularly through his interactions with fellow artists and the groundbreaking exhibitions held in Brussels.

A key figure in transmitting Neo-Impressionist ideas to Belgium was Théo van Rysselberghe, a compatriot and fellow member of Les XX. Van Rysselberghe had encountered Seurat's work in Paris and became a fervent advocate and practitioner of Pointillism. His influence on Schlobach and other Belgian artists was considerable, encouraging them to explore this new visual language. While the provided information mentions an attempt to fuse Monet's Impressionism with Paul Cézanne's Pointillism, it's more accurate to say Schlobach sought to integrate the Impressionistic concern for light and atmosphere with the Neo-Impressionist technique of Seurat and Signac. Cézanne, while a monumental influence on modern art, was not a Pointillist; his focus was more on underlying structure and form, though his broken brushwork did contribute to the evolving understanding of color application.

Les XX: A Catalyst for the Belgian Avant-Garde

The formation of Les XX (The Twenty) in 1883, with its first exhibition in 1884, marked a pivotal moment in Belgian art history, and Willy Schlobach was at its very heart as a founding member. This group emerged from a desire among younger, progressive artists to break free from the conservative constraints of the official Salon system, which often favored academic and traditional art. Les XX provided a platform for exhibiting more experimental and avant-garde works, not only by its Belgian members but also by invited international artists.

The membership of Les XX was diverse, encompassing a range of styles and artistic temperaments. Besides Schlobach and Théo van Rysselberghe, prominent members included the iconoclastic James Ensor, whose work veered towards Expressionism and Symbolism; Fernand Khnopff, a leading Symbolist painter; Henry Van de Velde, who began as a Neo-Impressionist painter before becoming a pioneering figure in Art Nouveau architecture and design; Georges Lemmen, another adopter of Pointillism; and Alfred William Finch, an Anglo-Belgian artist who also embraced Neo-Impressionism before turning to ceramics.

Les XX's annual exhibitions in Brussels became major cultural events, introducing the Belgian public and artistic community to the latest developments in European art. The group famously invited leading international artists to exhibit alongside them, including French masters such as Georges Seurat, Paul Signac, Claude Monet, Auguste Renoir, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, and Paul Cézanne, as well as figures like James McNeill Whistler from the Anglo-American sphere and the sculptor Auguste Rodin.

It was at a Les XX exhibition in 1887 that Seurat's monumental masterpiece, A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte, was shown in Brussels. This painting, a quintessential example of Pointillism, caused a considerable stir. While some, like Schlobach and Van Rysselberghe, were inspired by its innovative technique and theoretical underpinnings, many critics and members of the public found its "incomprehensible dotted language" challenging and even offensive. This controversy highlighted the radical nature of Neo-Impressionism and the crucial role Les XX played in championing such avant-garde movements, even in the face of resistance. Schlobach's involvement in Les XX placed him at the forefront of these artistic debates and developments.

Schlobach's Embrace of Pointillism and Artistic Style

Willy Schlobach fully embraced the principles of Neo-Impressionism, particularly the Pointillist technique, during the late 1880s and into the 1890s. His paintings from this period demonstrate a meticulous application of small dots or dabs of pure color, carefully juxtaposed to create effects of light, shadow, and vibrancy. Unlike the more spontaneous brushwork of the Impressionists, Schlobach's Pointillist works exhibit a controlled, almost scientific precision, reflecting the Neo-Impressionist aim of achieving optical mixing of colors in the viewer's eye rather than on the palette.

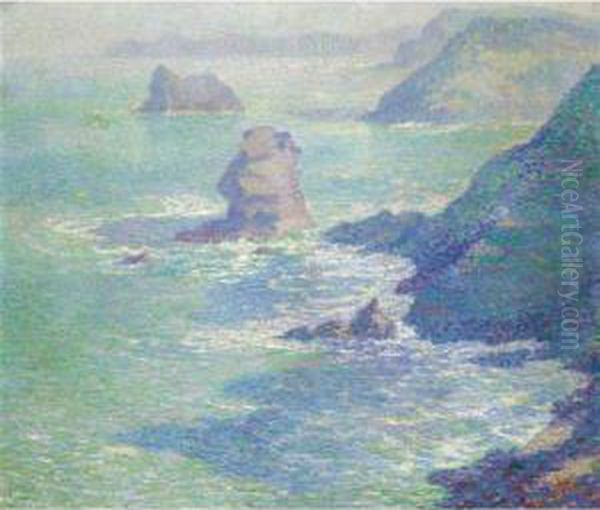

His subject matter often revolved around landscapes and coastal scenes, where the interplay of light on water and land provided ample opportunity to explore the nuances of Divisionist color theory. He was particularly drawn to the effects of natural light at different times of day and under various atmospheric conditions. Works depicting the Belgian coast, or locations like Belle-Île in Brittany (a site also favored by Monet), allowed him to capture the shimmering quality of light on the sea and the subtle gradations of color in the sky and on cliffs.

Schlobach's Pointillism was not merely a technical exercise; it was a means to convey a heightened sensory experience of the world. By breaking down color into its constituent parts, he sought to create images that were more luminous and vibrant than could be achieved through traditional methods of color mixing. His paintings often possess a serene, contemplative quality, inviting the viewer to engage with the scene on a deeply perceptual level. The careful construction of his compositions, combined with the systematic application of color, resulted in works that are both visually stimulating and harmoniously balanced.

Notable Works and Thematic Concerns

While a comprehensive catalogue of Willy Schlobach's oeuvre may not be as widely known as those of some of his contemporaries, several works and thematic concerns stand out. The titles mentioned in the provided information, such as Les falaises (The Cliffs/Coastline), point directly to his engagement with coastal landscapes. In such a work, one can imagine Schlobach employing his Pointillist technique to render the rugged texture of the cliffs, the dynamic movement of the waves, and the diffuse light of the sky, all through a mosaic of colored dots. The effect would be one of shimmering intensity, capturing the unique atmosphere of the seaside.

Summer flowers in a vase suggests that Schlobach also applied his Neo-Impressionist approach to still life. This genre would have allowed for a focused study of color interaction and light effects on a smaller, more controlled scale. The vibrant hues of the flowers and the play of light on the vase and surrounding surfaces would have been ideal subjects for the Pointillist method, enabling him to explore the full spectrum of color and its optical properties.

A particularly interesting work mentioned is A view of Wasserburg on the Lake Constance, dated around 1920. This painting is significant for several reasons. Firstly, its date suggests that Schlobach continued to work in a Neo-Impressionist or related style well into the 20th century, even as many other artists had moved on to new artistic idioms like Fauvism, Cubism, or Expressionism. This indicates a sustained commitment to the principles of light and color that had defined his earlier career. Secondly, the location, Wasserburg on Lake Constance (Bodensee), reflects a shift in his personal geography. Schlobach, who was of German parentage, eventually moved to Germany, settling in Nonnenhorn, also on Lake Constance. This later work likely depicts the serene beauty of this lakeside environment, rendered with the sensitivity to light and atmosphere that characterized his art. The depiction of water, with its reflective qualities, would have remained a compelling motif for his Pointillist-inspired technique.

His works consistently demonstrate a profound understanding of how light shapes our perception of the world. Whether depicting the bright sunlight on a coastal scene, the subtle ambiance of an interior, or the tranquil beauty of a lakeside view, Schlobach's primary concern was to capture the essence of light through color. This dedication to the optical and atmospheric qualities of a scene places him firmly within the lineage of artists who sought to expand the expressive possibilities of painting in the modern era.

Challenges, Evolution, and Later Career

The rigorous demands of the Pointillist technique, requiring patience and a methodical approach, were not suited to every artistic temperament. Many artists who experimented with Neo-Impressionism, including some members of Les XX, eventually moved towards other styles that allowed for greater spontaneity or different forms of expression. For instance, James Ensor developed a highly personal, often grotesque and satirical style, while Henry Van de Velde transitioned towards the flowing lines and organic forms of Art Nouveau.

Schlobach, however, appears to have maintained a longer allegiance to Neo-Impressionist principles, as evidenced by works like the 1920 view of Wasserburg. This suggests a deep conviction in the expressive power of Divisionist color theory. It is possible that his style evolved over time, perhaps incorporating looser brushwork or a modified approach to color application, but the core tenets of capturing light through carefully considered color relationships likely remained central to his practice.

His decision to eventually relocate to Germany, specifically to Nonnenhorn on Lake Constance, is a significant biographical detail. This move may have been influenced by his German heritage or other personal factors. Living by Lake Constance would have provided him with new landscapes and atmospheric conditions to explore in his art, continuing his lifelong fascination with the interplay of light, water, and nature.

Despite his important role in Les XX and his contribution to Belgian Neo-Impressionism, Willy Schlobach has not always received the same level of international recognition as some of his more famous contemporaries like Ensor or even Van Rysselberghe. This may be due in part to the dispersal of his works, his later career in Germany, or the art historical focus often being drawn to the more radical stylistic departures of other artists. However, his contribution remains undeniable.

Legacy and Conclusion

Willy Schlobach's legacy lies primarily in his role as a dedicated practitioner and proponent of Neo-Impressionism in Belgium. As a founding member of Les XX, he was part of a crucial avant-garde movement that transformed the artistic landscape of his country and helped to introduce groundbreaking international art to a Belgian audience. His commitment to the Pointillist technique, with its scientific basis and its aim of achieving heightened luminosity and vibrancy, resulted in works of great visual beauty and perceptual depth.

His paintings, whether depicting the rugged Belgian coast, tranquil lakeside scenes in Germany, or intimate still lifes, are testaments to a lifelong exploration of light and color. He skillfully adapted the principles of Seurat and Signac to his own artistic vision, creating a body of work that captures the fleeting effects of atmosphere and the enduring beauty of the natural world.

While perhaps not as widely celebrated as some of his peers, Willy Schlobach remains an important figure for understanding the richness and diversity of late 19th and early 20th-century art, particularly the development and dissemination of Neo-Impressionism beyond its French origins. His dedication to his craft, his involvement in the progressive artistic currents of his time, and his sensitive portrayals of light and nature ensure his place in the annals of art history. He was a bridge between artistic traditions and a quiet innovator whose meticulous brushstrokes illuminated the path for new ways of seeing.