Theo van Rysselberghe stands as a pivotal figure in Belgian art history, a painter whose career navigated the transition from academic traditions through Impressionism to become a leading proponent of Neo-Impressionism, also known as Pointillism. Born Théophile van Rysselberghe in Ghent, Belgium, on November 23, 1862, into a French-speaking bourgeois family, he was immersed in a cultured environment from a young age. His older brother, Octave van Rysselberghe, would also achieve fame as a prominent architect associated with Art Nouveau. This familial connection to the arts undoubtedly fostered Theo's own creative inclinations. His journey as an artist was marked by intellectual curiosity, influential friendships, extensive travel, and a constant evolution of style, leaving behind a rich legacy of luminous paintings and decorative works.

Early Training and Influences

Van Rysselberghe began his formal art education at the Academy of Fine Arts in Ghent before moving to Brussels to study at the Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts. A key figure in his early development was the director Jean-François Portaels, an artist known for his Orientalist themes. Portaels' influence likely encouraged Van Rysselberghe's own early interest in exotic subjects and potentially steered him towards a more academic, yet richly coloured, initial approach. During these formative years, he absorbed the prevailing realist traditions but soon began exploring the burgeoning styles emerging from France, particularly Impressionism.

The allure of different cultures and landscapes called to Van Rysselberghe early in his career. Between 1882 and 1888, he undertook three significant journeys to Morocco. These trips proved transformative for his artistic vision. The intense North African light, the vibrant colours of the local life, textiles, and landscapes pushed him away from the darker palettes often associated with Belgian realism. His brushwork became looser, more energetic, and his canvases began to glow with a newfound luminosity, reflecting the direct observation of light and atmosphere characteristic of Impressionism, even before his full conversion to Neo-Impressionism. These Moroccan paintings already hinted at his innate sensitivity to colour and light.

Les XX and the Avant-Garde Spirit

Returning to Brussels, Van Rysselberghe became a central figure in the Belgian avant-garde. In 1883, he was one of the founding members of the influential group Les Vingt (Les XX), or The Twenty. This group, organized by the lawyer and arts promoter Octave Maus, aimed to break free from the conservative constraints of the official Salons and academic traditions. Les XX became a crucial platform for showcasing progressive Belgian art alongside international innovations, particularly from France.

Through Les XX annual exhibitions, Van Rysselberghe and his colleagues introduced Belgian audiences to the latest developments in French art. They invited artists like Claude Monet, Auguste Renoir, Auguste Rodin, and later, Georges Seurat and Paul Signac, to exhibit alongside them. This created a dynamic cross-cultural exchange and positioned Brussels as a significant centre for modern art. Van Rysselberghe's involvement was not just as an exhibitor; he was an active participant, helping to shape the group's direction and fostering connections with artists across Europe, including James McNeill Whistler.

The Revelation of Neo-Impressionism

A defining moment in Van Rysselberghe's career occurred in 1886 during a visit to Paris for the eighth and final Impressionist exhibition. It was there that he encountered Georges Seurat's monumental painting, A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte. This work, with its systematic application of small dots of pure colour intended to blend in the viewer's eye (a technique known as Divisionism or Pointillism), was a revelation. Seurat, alongside Paul Signac and Camille Pissarro, was pioneering this new approach based on scientific colour theories developed by scientists like Michel Eugène Chevreul and Ogden Rood.

Deeply impressed by the luminosity and structure achieved through Seurat's method, Van Rysselberghe began to experiment with Pointillism himself. He saw its potential to render light and colour with unprecedented vibrancy and scientific rigor. He quickly became one of its most devoted and skilled practitioners outside of France, playing a crucial role in disseminating the style in Belgium through his own work and his activities within Les XX. He formed close friendships with the leading French Neo-Impressionists, particularly Seurat and Signac.

Mastering Pointillism: A Personal Interpretation

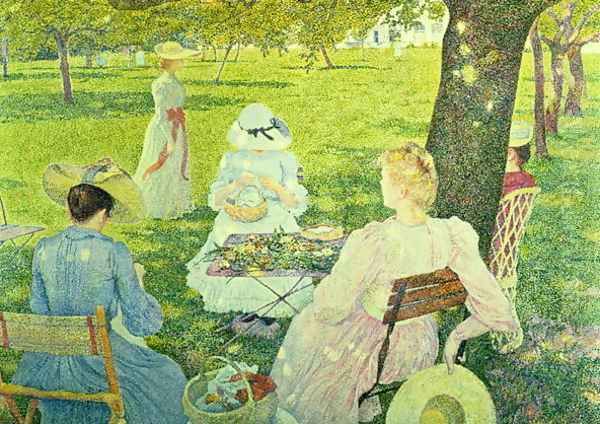

Van Rysselberghe fully embraced the Pointillist technique by the late 1880s. However, he did not merely imitate Seurat or Signac. While adhering to the core principles of optical mixing and the use of pure colour dots, he developed his own distinct interpretation. His dots were often slightly larger and less rigidly systematic than Seurat's, allowing for a greater sense of texture and a slightly softer, more atmospheric effect. He applied the technique to various genres, including landscapes, seascapes, portraiture, and genre scenes.

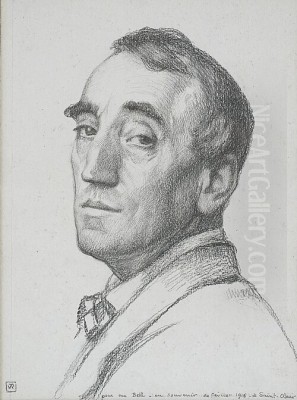

His Pointillist works are celebrated for their remarkable handling of light, capturing the shimmering quality of sunlight on water, the warmth of interiors, or the delicate nuances of skin tones. He excelled at portraiture within this demanding style, managing to convey not only a physical likeness but also the psychological presence of his sitters. This was a significant achievement, as the meticulous technique could sometimes lead to stiffness in the hands of less skilled artists.

Key works from his Neo-Impressionist period demonstrate his mastery. Tea in the Garden (likely referring to works like Family in the Orchard, c. 1890) exemplifies his ability to capture tranquil domestic scenes bathed in dappled sunlight, using colour dots to build form and atmosphere. His portraits, such as the sensitive Portrait of Denise Maréchal (1890) or the striking Portrait of Madame Charles Maus (wife of the Les XX secretary), showcase his skill in rendering individual character through the Divisionist method. The portrait Emile Verhaeren Reading (1901) captures his close friend, the poet, in a moment of quiet concentration, the light modelled meticulously through pointillist strokes.

His landscapes and seascapes, often painted along the Belgian and Mediterranean coasts, are particularly luminous. Works like Olive Trees near Nice and various coastal scenes demonstrate his fascination with the effects of light on natural forms, using contrasting colour dots to create vibrant and harmonious compositions. He travelled extensively with Signac, sailing along the Mediterranean coast, and these experiences directly informed many of his sun-drenched canvases from this period.

Friendships and Artistic Circles

Van Rysselberghe's life was enriched by strong friendships with fellow artists and intellectuals. His bond with Paul Signac was particularly close. They shared a passion for sailing and the sea, often travelling and painting together, especially in the South of France around Saint-Tropez. Signac even gifted Van Rysselberghe a painting of Saint-Tropez in 1893, testament to their mutual respect and camaraderie. Although their artistic paths eventually diverged somewhat, their friendship was a significant source of mutual support during the height of Neo-Impressionism.

He was also deeply connected to the Belgian literary world, most notably through his lifelong friendship with the Symbolist poet Emile Verhaeren. Van Rysselberghe painted several portraits of Verhaeren and his wife, Marthe, and also contributed illustrations and designs for Verhaeren's books, demonstrating his versatility across different artistic media. This connection highlights the close relationship between visual artists and writers within the Belgian avant-garde circles.

His involvement with Les XX and its successor, La Libre Esthétique, kept him in contact with a wide range of artists. Besides Seurat and Signac, he knew figures like Camille Pissarro, who also experimented with Pointillism for a time. His travels also brought him into contact with artists like John Singer Sargent and Ralph Curtis, with whom he visited Spain and Morocco. While in Paris, he visited the studio of Edgar Degas and admired the works of Claude Monet, absorbing lessons from various strands of modern art. His long correspondence with Octave Maus, spanning some thirty years, provides valuable insights into the artistic debates and collaborations of the era.

Evolution Towards a Later Style

Around 1903, and more definitively by 1910, Van Rysselberghe began to move away from the strict application of Pointillism. While his understanding of colour and light remained profound, his brushwork became broader and more fluid. The distinct dots gave way to larger strokes, although the principle of using juxtaposed colours often remained. This shift may have been influenced by the rise of Fauvism and other post-Neo-Impressionist trends, or perhaps a personal desire for greater freedom of expression.

His later works often focus on portraiture, female nudes, and serene landscapes, particularly scenes from the Mediterranean coast where he eventually settled. These paintings retain a sense of harmony and luminosity but possess a more relaxed, sometimes almost classical feel. He continued to produce portraits of notable figures and intimate depictions of family life. Works like Coastal Scene from this later period show a continued mastery of light and atmosphere, but rendered with a more direct and less systematic technique.

In 1911, seeking tranquility and perhaps distance from the bustling art centres of Paris and Brussels, Van Rysselberghe moved permanently to Saint-Clair in the Var region of Southern France. He continued to paint actively, focusing on the sunlit landscapes and intimate scenes that surrounded him. His connection to the Belgian art scene remained, but his life became more centred on his immediate environment and personal artistic pursuits.

Decorative Arts and Versatility

Beyond his significant contributions to easel painting, Van Rysselberghe was also active in the field of decorative arts, reflecting the period's interest in integrating art into everyday life, a key tenet of Art Nouveau. His brother Octave's profession as an architect likely facilitated some of these ventures. Theo designed posters, catalogues for Les XX, book illustrations (notably for Verhaeren), and even ventured into furniture design and possibly stained glass.

He collaborated with prominent figures of the Art Nouveau movement, including the architect Henry van de Velde. For instance, Van Rysselberghe created decorative panels and murals for some of Van de Velde's architectural projects. This aspect of his work demonstrates his versatility and his engagement with the broader artistic currents of his time, aiming to create unified aesthetic environments. His decorative work often carried the same sensitivity to line, colour, and harmonious composition found in his paintings.

Legacy and Influence

Theo van Rysselberghe died in Saint-Clair, France, on December 13, 1926, at the age of 64. He left behind a substantial body of work that marks him as a key figure in late 19th and early 20th-century European art. His primary achievement lies in his role as the foremost Belgian exponent of Neo-Impressionism. He masterfully adapted the Pointillist technique, creating works of exceptional luminosity, particularly in portraiture and landscape.

His influence extended through his participation in Les XX and La Libre Esthétique, helping to introduce modern French art to Belgium and fostering a vibrant national avant-garde scene. He served as a crucial link between French Neo-Impressionism and artists in Northern Europe. While he eventually moved beyond strict Pointillism, his entire oeuvre is characterized by a sophisticated understanding of colour theory and a remarkable sensitivity to the effects of light.

Although perhaps overshadowed internationally by his French contemporaries like Seurat and Signac, Van Rysselberghe's reputation has steadily grown. His works are held in major museums in Belgium and internationally, and they are highly sought after by collectors. Critical reappraisal, particularly from the late 20th century onwards, has solidified his position as a major artist whose technical brilliance was matched by a refined aesthetic sensibility. He remains celebrated for his ability to combine scientific precision with poetic beauty, capturing moments of quiet intimacy and the dazzling effects of light with equal mastery. His legacy is that of a dedicated, versatile, and highly influential artist who played a vital role in the development of modern painting.