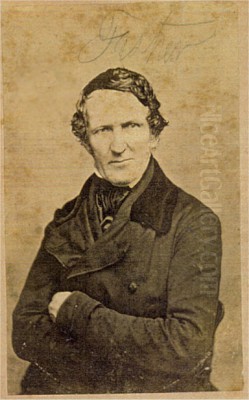

Alvan Fisher stands as a significant figure in the nascent stages of American art, particularly celebrated for his pioneering contributions to landscape and genre painting. Active during the first half of the 19th century, Fisher was among the earliest American artists to dedicate a substantial portion of his career to depicting the natural scenery and everyday life of his homeland, laying crucial groundwork for the later Hudson River School. His work captured the spirit of a young nation discovering its own identity and the beauty of its diverse terrains.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Born on August 9, 1792, in Needham, Massachusetts, Alvan Fisher spent his formative years in nearby Dedham, a town that would remain his lifelong home and a frequent source of inspiration. Unlike many of his European counterparts who benefited from established art academies and long traditions, Fisher emerged in an American cultural landscape where artistic careers were less defined and support systems were still developing. His decision to pursue art was reportedly supported by his family, an important factor in an era when such a profession was not always viewed as practical.

Fisher's formal artistic training began around the age of eighteen when he became an apprentice to John Ritto Penniman in Boston. Penniman was a versatile and well-regarded ornamental painter, sign painter, and portraitist. Under his tutelage, from approximately 1810 to 1814, Fisher would have learned a wide array of practical skills, including decorative painting, portraiture, and possibly even the painting of theatrical scenery. This broad training was typical for artists of the period, who often needed to be jacks-of-all-trades to make a living. Penniman's influence likely instilled in Fisher a strong sense of craftsmanship and a pragmatic approach to his art.

Launching an Independent Career

Around 1814 or 1815, Alvan Fisher embarked on his independent career. Initially, like many aspiring artists of his time, he focused on portraiture. Portraits were the most reliable source of income for American painters, as prominent citizens and families sought to have their likenesses preserved. Fisher began by offering his services at relatively modest prices, which helped him secure commissions and build a reputation in Boston and surrounding areas. He established his own studio in Boston, signaling his professional commitment.

However, Fisher's artistic interests soon expanded beyond the confines of portraiture. He was drawn to the American landscape, a subject that was only beginning to gain traction among native-born artists. He also developed an interest in genre scenes – depictions of everyday life, rural activities, and pastoral settings. This diversification was notable; while artists like Washington Allston had already achieved fame, the dedicated American landscape specialist was still a rarity. Fisher began to paint farm scenes, winter landscapes, and animal subjects, often imbuing them with a charming, anecdotal quality.

His early forays into these less conventional (for America at the time) subjects demonstrated a keen observational eye and a desire to capture the unique character of the American environment and its people. These works found an appreciative audience, and Fisher began to exhibit them regularly.

The Grand Tour: European Sojourn and Its Impact

In 1825, seeking to broaden his artistic horizons and study the masterpieces of European art, Alvan Fisher embarked on a Grand Tour of Europe. This was a common rite of passage for ambitious American artists who felt the need to immerse themselves in the older, more established art traditions of the Old World. His travels took him to England, France, Italy, and Switzerland, offering exposure to a vast range of artistic styles and subjects.

In London, he would have encountered the flourishing British school of landscape painting, with artists like J.M.W. Turner and John Constable (though their more radical innovations might have been less directly influential on Fisher than the established picturesque tradition). He also visited Paris, where he studied at a private academy and spent considerable time in the Louvre, copying Old Masters. The classical landscapes of Claude Lorrain and Nicolas Poussin, as well as the genre scenes of Dutch 17th-century painters, likely made a significant impression.

This European experience, which lasted about a year, was transformative. While Fisher remained committed to American subjects upon his return, his technique was refined, his compositions became more sophisticated, and his understanding of landscape conventions deepened. He learned how to better organize his canvases, manage light and shadow, and create a sense of depth and atmosphere, all while retaining his characteristic attention to detail and naturalism.

Pioneering American Landscape Painting

Upon his return to the United States in 1826, Alvan Fisher was one of a handful of artists, including Thomas Doughty and, slightly later, Thomas Cole, who were seriously committed to landscape painting as a primary focus. Fisher is often credited as being one of the first American artists to make a professional specialty of landscape painting, even opening what some consider the first dedicated landscape studio in Boston.

His landscapes often celebrated the specific character of the American Northeast. He painted scenes of rural tranquility, dramatic natural wonders, and the changing seasons. Winter landscapes, a theme he particularly favored, allowed him to explore the subtle harmonies of a muted palette and the crisp, clear light of a cold day. Works depicting activities like ice harvesting or sleigh rides captured a distinct aspect of New England life.

One of Fisher's most iconic subjects was Niagara Falls. Like many artists and writers of his era, he was captivated by the sublime power and grandeur of this natural wonder, which was increasingly seen as a symbol of America's unique identity and untamed wilderness. He painted Niagara Falls multiple times, from various viewpoints and under different conditions. His 1820 painting, The Great Horseshoe Fall, Niagara, is a notable example, showcasing the immense scale of the falls, often with small human figures included to emphasize the overwhelming power of nature, a common trope in Romantic landscape painting. These works resonated with a public eager for images that celebrated the nation's natural majesty.

Genre Scenes and Animal Painting

Alongside his landscapes, Alvan Fisher made significant contributions to American genre painting. He depicted scenes of farm life, country fairs, and rustic pastimes with a warmth and gentle humor that appealed to contemporary audiences. These paintings often told a story or captured a characteristic moment of rural existence. Works like The Corn Husking Frolic or scenes of farmers with their livestock provided a nostalgic and idealized vision of agrarian America, a vision that was becoming increasingly potent as the country began to industrialize.

Fisher also distinguished himself as one of America's earliest notable animal painters. He had a genuine interest in depicting livestock, particularly horses and cattle, often with a high degree of anatomical accuracy and individual character. Paintings such as Prize Bull or his various depictions of horse racing were relatively unusual in American art at the time. His skill in this area added another dimension to his rural scenes and demonstrated his versatility. These animal portraits were not just incidental elements but often the central focus, reflecting the importance of agriculture and animal husbandry in the American economy and culture.

Artistic Style, Techniques, and Themes

Alvan Fisher's artistic style can be characterized as a blend of detailed realism and a gentle Romantic sensibility. He was a keen observer of nature, and his paintings are typically filled with carefully rendered details of foliage, rock formations, and atmospheric conditions. This commitment to verisimilitude was a hallmark of early American landscape painting, reflecting a desire to accurately document the features of the New World.

At the same time, his work often evokes a sense of the picturesque or the idyllic. His landscapes are rarely wild or threatening; instead, they tend to present nature as harmonious and accessible, often populated by contented figures engaged in leisurely or productive activities. This approach aligned with the prevailing cultural mood, which celebrated the taming of the wilderness and the virtues of rural life.

A recurring theme in some of Fisher's work, particularly in paintings like Indigenous People Crossing a Frozen Lake, is a nostalgic or sympathetic portrayal of Native Americans. As the frontier expanded and Native American populations were increasingly displaced, some artists, Fisher among them, depicted them as figures within the landscape, sometimes tinged with a sense of melancholy for a vanishing way of life. This reflected a complex and often contradictory attitude prevalent in 19th-century America.

Fisher often incorporated small human figures into his landscapes, not just for scale, but to add narrative interest or a touch of humor. Picnicking couples, anglers, or travelers animate his scenes, inviting the viewer to imagine themselves within the depicted environment.

Exhibitions, Recognition, and the Art Market

Alvan Fisher was a commercially successful artist who understood the importance of exhibiting his work and cultivating a market. He regularly showed his paintings at prominent venues such as the Boston Athenaeum, which played a crucial role in fostering the arts in New England. He also exhibited at the National Academy of Design in New York and the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia, the leading art institutions in the country at the time. His work was generally well-received by critics and the public.

Fisher was also a shrewd businessman. He kept meticulous records of his paintings and sales, and it is estimated that he sold nearly a thousand works during his career, a remarkable number for the period. He produced paintings in various sizes and price ranges, making his art accessible to a broader clientele. He also created lithographs of some of his popular compositions, further expanding his reach. His painting Moonlit Figure by a Lake fetched ,775 at a later auction, and Tending Cows & Sheep sold for ,000 in 1974, indicating the enduring value of his work.

His paintings found their way into important collections, and today his works are held by institutions such as the White House, the National Gallery of Art, the Smithsonian American Art Museum, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, among many others.

Relationships with Contemporaries

Alvan Fisher was part of a burgeoning community of artists in Boston and the broader American art scene. He had both competitive and collaborative relationships with his peers.

He was a contemporary of Thomas Doughty (1793-1856), another key pioneer of American landscape painting. Fisher and Doughty are often mentioned together as the earliest American artists to specialize in landscape. They sometimes painted similar scenes and appealed to a similar market, leading to a degree of friendly rivalry. There is also evidence that they collaborated on or exhibited works together, for instance, with George Loring Brown (1814-1889), a younger landscape painter who also studied in Europe.

In the Boston art world, Fisher would have been aware of marine painter Robert Salmon (c.1775-c.1845), an English émigré whose detailed ship portraits and harbor scenes were highly popular and set a high standard for marine art. While their primary subjects differed, they were both significant figures in the Boston art market.

Fisher's career overlapped with the rise of Thomas Cole (1801-1848), who is often considered the founder of the Hudson River School. While Cole's landscapes tended towards grander, more allegorical themes, Fisher's more intimate and descriptive approach provided an important counterpoint and helped establish the taste for native scenery. Other artists who would become central to the Hudson River School, such as Asher B. Durand (1796-1886), were also his contemporaries. Durand, like Fisher, transitioned from another field (engraving) to landscape painting.

The broader artistic environment included prominent portraitists like Gilbert Stuart (1755-1828), whose career was concluding as Fisher's was maturing, and Chester Harding (1792-1866), a direct contemporary and competitor in portraiture. The influence of earlier Romantic painters like Washington Allston (1779-1843), who was a towering figure in Boston, would also have been part of the artistic milieu. Early landscape efforts by artists like Francis Guy (c.1760-1820) also predated or coincided with Fisher's initial work in the genre.

Artists focusing on other aspects of American life and nature, such as John James Audubon (1785-1851) with his monumental bird studies, or George Catlin (1796-1872) and Seth Eastman (1808-1875) with their depictions of Native American life, were also part of this vibrant period of American artistic exploration, each contributing to a growing visual record of the continent.

The Hudson River School Connection

While Alvan Fisher is not always categorized strictly as a member of the Hudson River School, he is undeniably a crucial precursor and foundational figure for this movement. The Hudson River School, which flourished from roughly the 1820s to the 1870s, was America's first true school of landscape painting. Its artists shared a common belief in the spiritual and aesthetic significance of American nature and sought to capture its beauty with detailed realism and often a Romantic sensibility.

Fisher's dedication to American scenery, his practice of sketching outdoors to capture natural effects, and his role in popularizing landscape as a worthy subject for American artists all paved the way for the Hudson River School. His work, along with that of Thomas Doughty, demonstrated that there was an audience and a market for American landscape painting. Artists like Thomas Cole, Asher B. Durand, Frederic Edwin Church (1826-1900), Albert Bierstadt (1830-1902), and Sanford Robinson Gifford (1823-1880) would build upon this foundation, taking American landscape painting to new heights of ambition and technical skill.

Fisher's emphasis on the specific character of the American landscape, rather than idealized or classical European scenes, was a key characteristic that would be adopted and expanded by the Hudson River School painters. His depictions of the White Mountains of New Hampshire, for example, prefigured the intensive exploration of this region by later artists.

Notable Works: A Closer Look

Several of Alvan Fisher's paintings stand out as representative of his style and thematic concerns:

The Great Horseshoe Fall, Niagara (1820): This early and ambitious depiction of Niagara Falls captures the sublime power of the cataract. The inclusion of small figures in the foreground emphasizes the immense scale of the natural wonder, a common device in Romantic art to evoke awe and humility before nature.

Indigenous People Crossing a Frozen Lake: This work reflects Fisher's interest in Native American subjects, portraying them within a stark winter landscape. It carries a sense of quiet dignity and perhaps a touch of melancholy, hinting at the changing relationship between European settlers and the original inhabitants of the land.

Winter in the Country (A Sleigh Ride): A quintessential example of Fisher's winter scenes, this painting depicts a lively sleigh ride, capturing the crisp atmosphere and the social customs of rural New England in winter. Such genre elements add charm and narrative to the landscape.

The Corn Husking Frolic: This genre scene celebrates a communal agricultural activity, portraying a lively gathering of figures engaged in husking corn. It idealizes rural labor and community spirit, reflecting a nostalgic view of agrarian life.

Prize Bull: An example of his skill in animal portraiture, this painting would have appealed to agricultural patrons and demonstrates his ability to capture the specific characteristics of an animal.

View of Springfield, Massachusetts: Fisher also painted townscapes, providing valuable historical records of American communities in the early 19th century. These works often combine topographical accuracy with a picturesque sensibility.

These and other works by Fisher demonstrate his versatility and his commitment to creating a distinctly American art.

Later Years and Enduring Legacy

Alvan Fisher continued to paint actively throughout his life, maintaining his studio in Dedham, Massachusetts. He remained a respected figure in the Boston art community and continued to exhibit his work. He adapted his style somewhat over the decades but largely remained true to his early interests in detailed, accessible depictions of American landscapes and genre scenes.

He passed away in Dedham on February 14, 1863, at the age of 70. By the time of his death, the American art scene had evolved considerably, partly due to the groundwork he had helped lay. The Hudson River School was at its zenith, and landscape painting was firmly established as a major American art form.

Alvan Fisher's legacy is that of a pioneer. He was among the first American artists to see the artistic potential in his native scenery and to make it a central focus of his career. He helped to create an appetite for American subjects among patrons and the public. His charming genre scenes provided a valuable record of early American life, and his animal paintings were an early contribution to that specialized field in America. While perhaps not as famous today as some of the later Hudson River School masters, Alvan Fisher's contributions were essential to the development of a national artistic tradition in the United States. He truly helped Americans to see and appreciate the beauty and character of their own land.