Introduction: A Singular Vision in American Art

Ralph Albert Blakelock stands as one of the most distinctive and poignant figures in the history of American art. Active during the latter half of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, he forged a unique path, diverging from the prevailing trends of his time to create deeply personal and evocative landscapes. Known primarily for his mesmerizing moonlit scenes and atmospheric depictions of nature, Blakelock's work occupies a space between the fading grandeur of the Hudson River School and the burgeoning subjectivity of modernism. His life, marked by profound artistic dedication, crushing poverty, mental illness, and eventual, albeit tragic, fame, adds layers of complexity to the understanding of his hauntingly beautiful paintings. He remains a quintessential American original, an artist whose vision was shaped by the wilderness, inner turmoil, and a relentless pursuit of a singular aesthetic.

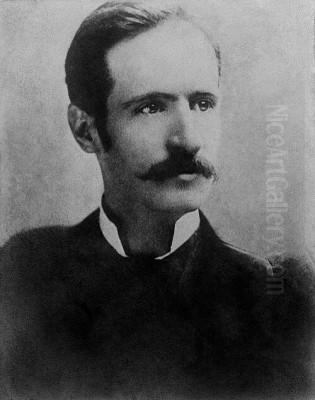

Early Life and the Turn to Art

Born in New York City on October 15, 1847, Ralph Albert Blakelock seemed destined for a different path. His father was a successful physician of English descent, and the expectation was that Ralph would follow in his footsteps. He dutifully enrolled at the Free Academy of the City of New York (now the City College of New York) in 1864, ostensibly to pursue medicine. However, the structured world of academia and the rigors of medical science held little appeal for the young man whose inclinations leaned towards the arts and music.

After only three years, Blakelock abandoned his formal studies, making the decisive choice to dedicate his life to painting. This decision marked a significant break from his family's expectations and set him on a course defined by self-reliance. Unlike many of his contemporaries who sought training in the established academies of Europe or under prominent American masters, Blakelock was largely self-taught. His artistic education was unconventional, pieced together through personal observation, experimentation, and an innate sensitivity to the natural world.

A crucial early influence was his uncle, James Arthur Johnson, an amateur artist and musician himself. Johnson provided encouragement and perhaps some informal guidance, fostering Blakelock's nascent talents. Through his uncle, Blakelock may have gained some exposure to the New York art scene and the work of established painters. Some accounts suggest connections to artists like James Renwick Brevoort, a landscape painter associated with the second generation of the Hudson River School, and possibly even the renowned Frederic Church, though the extent of direct mentorship remains unclear. Ultimately, Blakelock's artistic development was primarily driven by his own explorations and an independent spirit.

The Call of the West: Shaping an Artistic Identity

A pivotal period in Blakelock's development occurred between 1869 and 1872 when he embarked on extensive travels through the American West. This journey, undertaken alone, took him far from the familiar landscapes of the East Coast, through territories including Kansas, Colorado, Wyoming, Utah, Nevada, California, and possibly into Mexico and Panama. This was not the grand tour of European cultural centers favored by many artists; instead, it was an immersion in the raw, untamed wilderness of America and an encounter with its indigenous peoples.

These travels profoundly impacted Blakelock's artistic vision. He spent considerable time observing and sketching the vast landscapes, dramatic geological formations, and unique light conditions of the West. Crucially, he also lived among various Native American tribes, gaining firsthand experience of their cultures and ways of life. This was a departure from the often-romanticized or purely ethnographic depictions common at the time; Blakelock seemed genuinely interested in the atmosphere and daily existence of these communities.

The Western experience provided Blakelock with a rich repository of subjects and moods that would dominate his mature work. The vast, lonely plains, the silhouetted forms of trees against twilight skies, and the intimate scenes of Native American encampments became recurring motifs. His palette began to darken, and his focus shifted from the detailed topographical rendering characteristic of the earlier Hudson River School painters like Thomas Cole or Asher B. Durand towards a more subjective and atmospheric interpretation of nature. The West imprinted itself on his artistic soul, providing the raw material for his unique brand of landscape painting.

Forging a Unique Style: Tonalism and Subjectivity

Returning to the East, Blakelock began to synthesize his experiences and observations into a highly personal artistic style. While his early works showed the influence of the Hudson River School's detailed naturalism, his mature style aligned more closely with the emerging Tonalist movement, though he remained fiercely individualistic. Tonalism, practiced by artists like George Inness, Dwight Tryon, and Alexander Helwig Wyant, emphasized mood, atmosphere, and harmonious color schemes, often depicting landscapes at dawn, dusk, or in hazy conditions.

Blakelock pushed Tonalist principles in a unique direction. He became known for his rich, dark palettes, often dominated by deep greens, browns, and resonant blacks, punctuated by areas of glowing light, particularly the moon or sunset. His technique was unconventional and laborious. He would build up layers of paint, often applying, scraping away, and reapplying pigment, sometimes incorporating varnish and bitumen into his layers. This process resulted in complex, textured surfaces that often developed a craquelure (a network of fine cracks) over time, adding to the aged, mysterious quality of his work.

His approach was deeply subjective, aiming to capture not just the appearance of a landscape but its emotional resonance and spiritual essence. Detail was often sacrificed for overall effect. Trees became intricate, lace-like silhouettes against luminous skies, and forms were simplified to enhance the poetic mood. His work shares a certain mystical quality with that of his contemporary Albert Pinkham Ryder, another visionary painter who operated outside the mainstream. However, where Ryder often drew on literary or mythological themes, Blakelock's inspiration remained rooted in the American landscape, transformed through memory and imagination. His style was also influenced by the French Barbizon School painters like Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot and Charles-François Daubigny, known for their atmospheric landscapes painted directly from nature, though Blakelock's process was more studio-based and imaginative.

Signature Themes: Moonlight and Memory

Perhaps Blakelock's most iconic and sought-after works are his nocturnes – paintings bathed in the ethereal glow of moonlight. These scenes became his signature, embodying his unique ability to blend observation with profound introspection. The moon, often partially obscured by clouds or filtered through intricate webs of branches, serves as a focal point, casting a mysterious, silvery light over the landscape.

Works like Moonlight (the title given to several variations), Moonlight on the Brook, and Moonlight on Long Island Sound exemplify his mastery of this theme. He achieved the luminous quality of moonlight through careful layering and juxtaposition of dark, opaque passages with areas where lighter underpainting or ground layers subtly shine through. The effect is not one of sharp, clear light, but rather a soft, pervasive radiance that seems to emanate from within the canvas itself.

These moonlit scenes are imbued with a sense of quietude, solitude, and often melancholy. They evoke a dreamlike state, transporting the viewer to a world both recognizable and strangely unfamiliar. Blakelock, who was also a passionate musician and sometimes improvised on the piano while working, seemed to translate musical harmonies and moods into visual terms. Some have likened the feeling of his nocturnes to the romantic compositions of composers like Ludwig van Beethoven, whose Moonlight Sonata resonates with a similar blend of beauty and sorrow. These paintings are less about specific locations and more about universal feelings evoked by nature in its most mysterious guise, filtered through the artist's memory and emotional state. His approach contrasts with the more objective, albeit atmospheric, nocturnes of James Abbott McNeill Whistler, focusing more on texture and inner feeling.

The Native American Subject: Romanticism and Reality

Blakelock's depictions of Native American life represent another significant aspect of his oeuvre. Stemming directly from his Western travels, these paintings, often titled Indian Encampment or similar variations, typically show small groups of figures and teepees nestled within a landscape, frequently silhouetted against a glowing sunset or bathed in moonlight.

Unlike the earlier, more documentary approach of artists like George Catlin or Karl Bodmer, Blakelock was not primarily concerned with ethnographic accuracy. His focus remained on mood and atmosphere, integrating the Native American presence seamlessly into his broader vision of the American wilderness. The figures are often small in scale, dwarfed by the surrounding nature, suggesting a harmonious, if perhaps vanishing, existence within the landscape.

There is an undeniable element of Romanticism in these portrayals. They tap into the nineteenth-century fascination with the "noble savage" and the perceived spirituality of Native American cultures. However, grounded in his personal experiences, Blakelock's depictions often possess an intimacy and quiet dignity that distinguishes them from more generic or stereotypical representations. The encampments glow with the warm light of campfires against the encroaching darkness, creating scenes of peaceful community amidst the vastness of nature. These works reflect both the artist's genuine encounters and the prevailing cultural attitudes of his time, filtered through his unique stylistic lens.

Struggle and Recognition: A Paradoxical Career

Despite the profound originality and beauty of his work, Blakelock's career was fraught with financial hardship and a lack of recognition during most of his productive years. He married Cora Rebecca Bailey in 1877, and the couple eventually had nine children. Supporting such a large family solely through his art proved an immense struggle. Blakelock was reportedly unbusinesslike and easily taken advantage of by dealers and collectors. He often sold his paintings for desperately low prices – sometimes as little as $25 – just to provide for his family's basic needs.

The constant pressure of poverty, combined with the frustration of seeing his unique vision undervalued, took a heavy toll on his mental state. He felt increasingly isolated from the mainstream art world, which favored European styles or the more polished academicism promoted by institutions like the National Academy of Design. His unconventional techniques and dark, moody subjects did not align with popular tastes of the time.

Ironically, recognition began to grow just as Blakelock's mental health deteriorated significantly. While he was confined to psychiatric institutions, his work started to attract serious attention from discerning collectors and critics. Prices for his paintings began to climb dramatically in the early twentieth century. The ultimate, tragic irony occurred in 1916 at the landmark Catholina Lambert collection auction. While Blakelock himself was institutionalized and largely unaware, his painting Moonlight fetched the astonishing price of $20,000 – a record for a work by a living American artist at the time, reportedly surpassing prices achieved for works by European masters like Claude Monet and Pierre-Auguste Renoir in the same sale. That same year, he was elected a full Academician by the National Academy of Design, an honor that came far too late to benefit him personally or financially.

The Descent into Shadow: Mental Health Challenges

The immense pressures of his life culminated in severe mental health issues for Blakelock. He suffered his first major breakdown in 1891, reportedly triggered by a dispute with a collector over the price of a painting and the overwhelming stress of his financial situation. Although he recovered temporarily, his mental state remained fragile. In 1899, he experienced a final, catastrophic breakdown, exhibiting delusions of grandeur and paranoia. He was diagnosed with dementia praecox, a term then used for what is now largely understood as schizophrenia.

From 1899 until shortly before his death in 1919, Blakelock spent most of his time confined to psychiatric hospitals, primarily the Middletown State Homeopathic Hospital in upstate New York. His confinement coincided paradoxically with his rise to fame in the art market. This narrative captured the public imagination, feeding into the Romantic trope of the "mad genius" – the artist whose brilliance is inextricably linked to, or perhaps caused by, mental instability. Newspapers sensationalized his story, portraying him as a forgotten master whose mind had succumbed to the pressures of unrecognized talent and poverty.

During his institutionalization, Blakelock continued to create art, producing numerous small drawings and paintings. However, the quality and nature of this later work are subjects of debate among art historians. Many pieces from this period are considered less complex and powerful than his earlier masterpieces, perhaps reflecting his diminished mental state or the limited materials available to him. Nevertheless, his tragic circumstances undoubtedly contributed to the mystique surrounding his name and the escalating value of his earlier works. His death on August 9, 1919, near Elizabethtown, New York, shortly after being released from the hospital under the care of a controversial benefactor, marked the end of a profoundly troubled but artistically significant life. The New York Times obituary lauded him as "one of America's greatest artists."

The Problem of Forgery: A Complicated Legacy

Blakelock's soaring posthumous fame and the high prices his paintings commanded created an unfortunate side effect: a rampant market for forgeries. Because the artist himself was institutionalized and unable to authenticate works or control his output during the peak years of his popularity, unscrupulous individuals flooded the market with fake Blakelocks. These forgeries often mimicked his famous moonlight scenes and Native American encampments, sometimes artificially aged to replicate the characteristic craquelure of his genuine works.

The sheer number of fakes produced has made the authentication of Blakelock's oeuvre exceptionally challenging for scholars, collectors, and museums. It is estimated that the number of forgeries may vastly exceed the number of authentic works. His daughter, Marian Blakelock, devoted considerable effort to identifying genuine pieces and exposing fakes, but the problem persists. This proliferation of counterfeit works has complicated the study of his art and occasionally cast doubt on the provenance of even well-regarded pieces. It stands as a cautionary tale about the intersection of art, fame, and market forces, particularly when an artist is vulnerable or incapacitated. Establishing a definitive catalogue raisonné of his work remains a complex task due to this legacy of imitation.

Blakelock's Place in Art History: Romanticism, Tonalism, and Modernism

In the broader narrative of American art history, Ralph Albert Blakelock occupies a unique and significant position. He is firmly rooted in the Romantic tradition, with his emphasis on emotion, subjectivity, and the sublime power of nature. His work represents a late flowering of nineteenth-century Romantic landscape painting, but with a distinctly modern sensibility.

He is a key figure in American Tonalism, yet his style transcends easy categorization. His intensely personal vision, unconventional techniques, and focus on inner psychological states pushed beyond the gentler harmonies of many Tonalist painters like J. Francis Murphy or Charles Warren Eaton. His work, alongside that of Albert Pinkham Ryder, represents the more visionary and mystical strain of American painting at the turn of the century.

Blakelock is often cited as a precursor to American modernism. His move away from literal representation towards expressive abstraction, his focus on the materiality of paint and surface texture, and his exploration of subjective emotional states anticipate developments in twentieth-century art. While direct influence on later movements like Abstract Expressionism is difficult to trace due to his isolation, the emotional intensity and textured surfaces found in the work of artists like Clyfford Still or Jackson Pollock share a distant kinship with Blakelock's radical approach to paint handling. His individualism set him apart from contemporaries focused on realism like Thomas Eakins or impressionistic light like Childe Hassam. While perhaps less overtly narrative than Winslow Homer, his landscapes carry a powerful psychological weight. His atmospheric effects might even find parallels in the mood-drenched works of European Symbolists like Odilon Redon.

Legacy and Conclusion: An Enduring Enigma

Ralph Albert Blakelock's legacy is multifaceted. He left behind a body of work that is instantly recognizable and deeply moving, celebrated for its poetic beauty and technical innovation. His moonlit landscapes, in particular, have secured his place as one of America's most original painters, a master of mood and atmosphere. His life story, however, adds a layer of tragedy and complexity to his artistic achievements. The narrative of struggle, mental illness, and belated fame has often threatened to overshadow the work itself, contributing to a mystique that is both compelling and potentially distorting.

Despite the challenges of forgery and the complexities of his biography, Blakelock's art continues to resonate. He stands as a testament to the power of individual vision in the face of adversity. His paintings invite contemplation, drawing viewers into landscapes that are simultaneously external and internal, reflecting the beauty of the American wilderness and the depths of the human psyche. He remains an enduring enigma in American art – a truly original voice whose hauntingly beautiful works continue to speak across the decades, reminding us of the profound connections between nature, memory, and the enduring mysteries of the human spirit.